Clinical Trials

The goals of clinical cancer research are to improve the therapeutic outcomes for cancer patients and to improve the quality of care. Important progress in cancer therapy has been possible because of clinical trials, but public confidence and support have waned because of past abuses and mistakes. However, without the benefit of experimentation, new and improved treatments will never be tested, and the important questions that need to be asked will never be answered. Good clinical trials need the support of both clinicians and patients. For this to happen, clinical trials must be carefully planned to ensure that the physical, moral, and ethical welfare of patients is safeguarded. This chapter deals with cancer drug development and the clinical trials system, from concept to implementation. It also deals with the mechanisms that protect the rights of human subjects and discusses the responsibilities of the nurse who takes care of them.

According to federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects, research is “the systematic investigation, including research development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalized knowledge” (National Commission, 1991). Two historical events greatly affected the establishment of federal regulations to protect the rights of human subjects involved in research: the Nuremberg Trial in 1946 and the Tuskegee Disclosure in 1972. As a result, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) was

created to monitor and review research, and the National Research Act (1994) established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. This group wrote the Belmont Report, which governs the ethical conduct of biomedical research.

created to monitor and review research, and the National Research Act (1994) established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. This group wrote the Belmont Report, which governs the ethical conduct of biomedical research.

The three principles on which the protection of human subjects is based are autonomy, beneficence, and justice. Autonomy requires respecting a person’s self-determination and refraining from obstructing a person’s actions unless those actions are clearly detrimental to others. It also includes protecting a person who has diminished autonomy. Beneficence refers to the principle of “doing no harm,” as stated in the Hippocratic oath, and of maximizing possible benefits and minimizing possible risks. The principle of justice addresses fairness in the distribution of the benefits and burdens of scientific research.

The process of translating the new knowledge gained from the bench (basic research) is long and expensive. Drug development starts with the acquisition and screening of chemical compounds. Screening is done on these compounds using animal or human cancer cells grown in vitro, transplanted animal tumors, and human xenografts. Then, animal toxicology studies and pharmacokinetic measurements are undertaken to provide vital information about the drug’s metabolism, half-life, absorption, excretion, and clearance. These studies enable the scientist to formulate an initial dose and schedule that would be acceptable for testing in humans.

When the preclinical trial is completed, an investigational new drug application is filed with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Before it approves a research protocol, the FDA requires documentation stating that the research will be done according to ethical standards and giving the name of the IRB, if applicable, that will be responsible for monitoring and evaluating the study.

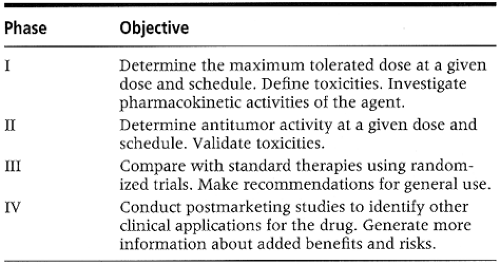

Agents being tested progress through the phases of the clinical trial (Table 3-1). In a phase I setting, new drugs (alone or

in combination) are tested to assess toxicity and to determine the maximum tolerated dose. Another objective of a phase I study is to determine biochemical events associated with the new drug (Simon & Friedman, 1992). This is achieved by performing pharmacokinetic studies. The data that are gathered are helpful in assessing the activity or toxicity of a new agent. Phase II trials determine the antitumor activity of a drug or a combination of drugs against a particular cancer type. Patients in this phase usually receive 75% to 90% of the maximum tolerated dose to prevent any severe toxicity. The primary end point is tumor response, as evidenced by shrinkage in the tumor in patients with measurable disease. Once the antitumor activity of the new agent is established in a phase II study, the efficacy of the new treatment is compared with a current standard regimen. Phase III follows, and patients who are entered on this level are usually randomized. The sample sizes required are large, necessitating multi-institutional co-operative group trials. Randomization is important and is undertaken to prevent biases.

in combination) are tested to assess toxicity and to determine the maximum tolerated dose. Another objective of a phase I study is to determine biochemical events associated with the new drug (Simon & Friedman, 1992). This is achieved by performing pharmacokinetic studies. The data that are gathered are helpful in assessing the activity or toxicity of a new agent. Phase II trials determine the antitumor activity of a drug or a combination of drugs against a particular cancer type. Patients in this phase usually receive 75% to 90% of the maximum tolerated dose to prevent any severe toxicity. The primary end point is tumor response, as evidenced by shrinkage in the tumor in patients with measurable disease. Once the antitumor activity of the new agent is established in a phase II study, the efficacy of the new treatment is compared with a current standard regimen. Phase III follows, and patients who are entered on this level are usually randomized. The sample sizes required are large, necessitating multi-institutional co-operative group trials. Randomization is important and is undertaken to prevent biases.

After these three phases are completed, a new drug application is submitted to the FDA. In 1992, it took the FDA an average of 19 months to approve a new drug. With the dramatic changes in health care, reforms to accelerate the approval process have been implemented. When the application is approved, the drug then becomes available in the market. It is estimated that it costs $50 to $70 million and takes approximately 6 to 12 years to develop a new drug.

Phase IV focuses on postmarketing studies and the collection of more data on the new treatment.

A research protocol is a guideline ensuring the consistent administration of an experimental procedure or treatment. It includes these important components:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree