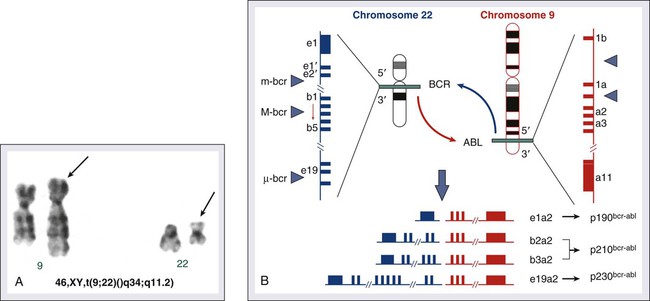

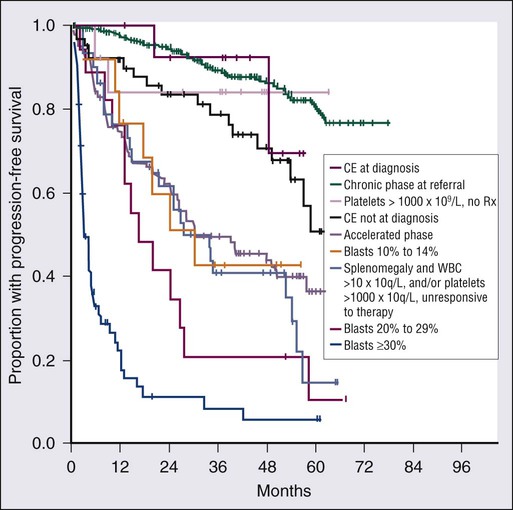

Hagop Kantarjian and Jorge Cortes • About 5000 cases of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) occur per year in the United States; CML represents 15% of all leukemias. • Median age is 55 to 60 years at diagnosis. • Common findings include fatigue, anemia, abdominal discomfort, splenomegaly, and leukocytosis. • At diagnosis 40% to 50% of patients are asymptomatic. • White blood cell count is usually greater than 50 × 109 cells/L, with a left-shifted differential, basophilia, and thrombocytosis. • Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia • Other myeloproliferative disorders • History and physical examination, complete blood cell count with differential and platelet count, and chemistries • Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy • Testing for the presence of the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome by cytogenetic analysis; testing for the presence of the BCR-ABL fusion gene by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis • Hydroxyurea or a BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI; e.g., imatinib mesylate, nilotinib, dasatinib) is given initially to control leukocytosis and thrombocytosis. • Imatinib induces a complete hematologic and cytogenetic response in most patients; estimated 8- to 10-year survival rate is 85% (93% if only CML-related deaths considered). • Randomized studies of frontline therapy with second-generation TKIs (e.g., nilotinib, dasatinib) show better results than those of imatinib. • New TKIs (e.g., dasatinib, nilotinib, bosutinib, ponatinib) are active after imatinib failure. • Allogeneic stem cell transplantation may be curative but is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. Chronic myeloid (or myelogenous) leukemia (CML) is a clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorder. It is characterized by overproduction of myeloid cells, a result of excessive proliferation, and reduced apoptosis. Clinical findings include fatigue, splenomegaly, leukocytosis, and anemia. Basophilia and thrombocytosis are common.3–3 CML is defined by the presence of a characteristic cytogenetic abnormality, the Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome, a reciprocal balanced translocation between the long arms of chromosome 9 and 22, t(9;22)(q34;q11.2). This results in a BCR-ABL fusion gene, which is causally related to the disease pathophysiology.6–6 CML accounts for 15% of cases of leukemia in the United States. There is a slight male preponderance (male-to-female ratio, 1.6 : 1). Its annual incidence is about 1.5 cases per 100,000 individuals. About 5,000 cases of CML are diagnosed annually. This incidence has not changed during the past few decades, and it increases with age. The median age at diagnosis is 55 to 65 years; it is uncommon in children and adolescents; only 2.7% of patients with CML are younger than 20 years.7 Before imatinib therapy, the prevalence of CML was about 25,000 cases in the United States. Now that the annual mortality after imatinib therapy has been reduced to 2% or less, the prevalence of CML will continue to rise, reaching a plateau (in the next 20 years) at about 180,000 cases (when the annual incidence will equal the annual mortality: based on a hazard risk of annual mortality of 1.5 for patients with CML compared with age-matched healthy individuals).8 This increase will change CML from an uncommon disorder to a prevalent one. There are no known familial associations in CML. Its risk is not increased in monozygotic twins or in relatives of patients with CML. There are no known common etiologic agents identified in CML. Ionizing radiation (exposure to nuclear bombs or accidents; radiation treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and cervical cancer) has increased the risk of CML. Its peak incidence is 5 to 10 years after exposure and is dose related. The risk of CML is not increased in individuals working in the nuclear industry. Radiologists working without adequate protection (before 1940) had an increased risk of developing CML, but no such risk has been found in recent studies. Benzene exposure increases the risk of acute myelogenous leukemia but not of CML. CML is not a frequent secondary leukemia after treatment of other cancers with radiation and/or alkylating agents.9,10 The Ph chromosome abnormality is present in more than 90% of patients with typical CML (Fig. 101-1). It results from a balanced reciprocal translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 9 and 22, t(9;22)(q34;q11.2). It is found in hematopoietic cells but not in other human cells. Its origin is close to the pluripotent stem cell, and it is present in erythroid, myeloid, monocytic, and megakaryocytic cells, less commonly in B lymphocytes, rarely in T lymphocytes, but not in marrow fibroblasts. The breakpoint of chromosome 9 results in translocation of the cellular oncogene ABL1 to a region on chromosome 22 coding for the major breakpoint cluster region (BCR). ABL1 is a homolog of V-ABL, the Abelson virus that causes leukemia in mice. This juxtaposes a 5′ portion of BCR to a 3′ position of ABL1 and produces a new hybrid oncogene, BCR-ABL. This codes for a novel BCR-ABL oncoprotein of molecular weight 210 kDa (p210BCR-ABL). The p210BCR-ABL oncoprotein results in uncontrolled kinase activity, which causes excessive proliferation and reduced apoptosis of CML cells,13–13 leads to a growth advantage of CML cells to normal cells, and suppresses normal hematopoiesis. The normal stem cells, although suppressed, persist and reemerge after effective therapy of CML. In Ph-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia, the breakpoint in BCR often occurs in a more centromeric region called the minor BCR region (mBCR). This produces a smaller BCR gene opposing ABL1, and therefore a fusion gene, messenger RNA, and BCR-ABL oncoprotein (p190BCR-ABL) of smaller sizes. A third rare breakpoint distal to the major BCR region, called µ-BCR, produces a p230BCR-ABL hybrid oncoprotein associated with a very indolent course of CML (see Fig. 101-1).14 What causes the BCR-ABL molecular rearrangement is unknown. Molecular techniques that amplify detection of BCR-ABL to 1 in 108 detect it in marrow cells of 25% to 30% of normal adults, in 5% of infants, but not in cord blood.15 Because CML develops in only 1.5 of 100,000 individuals (i.e., 1 to 2 per 25,000 to 30,000 individuals who express BCR-ABL in their bone marrow), additional molecular events or lack of immune recognition of the clonal cells may contribute to the development of CML. The fusion BCR-ABL gene and the p210 oncoprotein can be found in some patients with typical morphologic CML, in whom the t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) is not identified. These patients have a response to therapy and a survival rate similar to those with Ph-positive cases. Patients with Ph-negative and BCR-ABL-negative CML (see later discussion) constitute a different entity (atypical CML) and have a worse prognosis.16,17 The molecular pathophysiology of CML transformation is poorly understood. Several molecular events have been associated with CML transformation, including point mutations or deletions in the TP53 tumor suppression gene, MYC amplification, deletions in the CDKN2A tumor suppressor gene, alteration of the RB retinoblastoma gene, and others. The causal relation of these events to transformation is not clear. Experimental models have established a causal relationship between the BCR-ABL molecular events and the development of CML. Transgenic mice that express Bcr-Abl developed acute leukemia. A Bcr-Abl–expressing retrovirus used to infect murine bone marrow cells that later repopulate irradiated mice resulted in myeloproliferative disorders, including a CML-like syndrome.20–20 Bcr-Abl, under the control of a tetracycline-repressible promoter, expressed in mice, resulted in a lymphoid leukemia that reversed in the presence of tetracycline,21 attesting to the leukemic potential of Bcr-Abl as a sole oncogenic abnormality. The recapitulation of CML-like disorders in animal models mediated by the Bcr-Abl molecular events established them as a root cause for CML and a legitimate molecular target for therapeutic interventions with TKIs. Common signs and symptoms of CML, when present, result from anemia and splenomegaly. These include fatigue, weight loss, malaise, early satiety, and left upper quadrant fullness or pain (Table 101-1). Rare manifestations include bleeding (associated with a low platelet count and/or platelet dysfunction), thrombosis (associated with thrombocytosis and/or marked leukocytosis), gouty arthritis (from elevated uric acid levels), priapism (usually with marked leukocytosis or thrombocytosis), retinal hemorrhages, and upper gastrointestinal ulceration and bleeding (from elevated histamine levels due to basophilia). Leukostatic symptoms (dyspnea, drowsiness, loss of coordination, confusion) caused by sludging in the pulmonary or cerebral vessels, are uncommon in chronic-phase CML despite white blood cell (WBC) counts exceeding 100 × 109 cells/L. Table 101-1 Features of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Philadelphia Chromosome–Positive Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia in Chronic Phase Referred to MD Anderson Cancer Center (1990–present; N = 1469) The bone marrow is hypercellular with marked myeloid hyperplasia. The myeloid-to-erythroid ratio is usually 15 : 1 to 20 : 1. About 15% of patients have 5% or more blast cells in the peripheral blood or bone marrow at diagnosis. Increased reticulin fibrosis is common (30% to 40% grade 3/4 reticulin fibrosis by silver staining), but collagen fibrosis is rare at presentation.22 Interestingly, whereas the “spent phase” of myelofibrotic CML was commonly reported in the past (with busulfan therapy) as an end-stage CML event, it has become uncommon in the eras of IFN-α and imatinib therapy. Imatinib effectively reduces myelofibrosis in CML.23,24 The definitions of accelerated and blastic phases of CML are shown in Table 101-2. In most patients the transformation from chronic to advanced phase is insidious, with the disease becoming more difficult to control. This phase is referred to as the accelerated phase. The criteria of accelerated phase are variable. In one study, features that correlated with a median survival of 18 months or less included a blast percentage equal or greater than 15%, blasts plus promyelocytes equal or greater than 30%, basophils equal or greater than 20%, a platelet count less than 100 × 109 cells/L unrelated to therapy, and cytogenetic clonal evolution.25 Features of accelerated-phase CML should be revisited because some (e.g., clonal evolution more favorable, blasts >15% less favorable) have different prognostic implications from recent studies (Fig. 101-2).26 Five to 10 percent of patients are seen in the accelerated phase; these patients have an estimated 8-year survival rate of 75% when treated frontline with TKIs.27 The accelerated phase is also associated with worsening anemia and splenomegaly, organ infiltration (liver, lymph nodes, skin, bones, or other tissues), and constitutional symptoms (aches, fever, malaise, weight loss). Table 101-2 Definitions of the Accelerated and Blastic Phases of Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia CE, clonal evolution; NA, not applicable; WBC, white blood cells. *These criteria were also used in all the IFN-α and tyrosine kinase inhibitors studies. Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplifies the region around the junction between BCR and ABL1. It is highly sensitive for the detection of minimal residual disease. PCR testing can either be qualitative, providing information about the presence of the BCR-ABL transcript, or quantitative, assessing the amount of BCR-ABL transcripts. Qualitative PCR may be useful for diagnosis of CML; quantitative PCR (qPCR) is ideal for monitoring response to therapy and is usually performed by real-time PCR. Simultaneous peripheral blood and marrow PCR studies show a high level of concordance. False-positive and false-negative results can happen with PCR. False-negative results may be from poor-quality RNA or failure of the reaction or from atypical transcripts (e.g., b3a3); false-positive results can be due to contamination. A 0.5- to 1-log coefficient of variability in some samples can occur depending on testing procedures, sample handling, and laboratory experience.28,29 The improved rates of complete cytogenetic response and of molecular response with imatinib now require new techniques that measure these responses more accurately (rather than relying on evaluation of only 20 metaphases by routine cytogenetic studies), with less painful procedures (peripheral blood rather than marrow samples), and with methods that measure minimal disease below the level of detection by routine karyotypic analysis (molecular studies). FISH studies can assess rapidly the disease status in 200 cells; this assessment may be done in cells in interphase and can be performed on blood specimens. Real-time PCR studies usually measure the ratio of the abnormal message, BCR-ABL, to a control gene (e.g., ABL). Because this is variable by laboratory and with time, efforts are ongoing to standardize the measurement of BCR-ABL transcripts in relation to an international standard (IS).30 Recent monitoring procedures in CML have emphasized replacing bone marrow studies (cytogenetics) with peripheral blood studies (FISH, qPCR) as more reliable and measuring deeper levels of response to TKIs. FISH studies are reliable in patients in complete cytogenetic response with a strong concordance between negative FISH studies and complete cytogenetic response. However, the concordance between the percent of Ph positivity by FISH and cytogenetic studies is not perfect. Recently, landmark studies have emphasized the importance of BCR-ABL transcripts of 10% or less as early indicators for response and long-term prognosis and that the finding of BCR-ABL transcripts of 1% or less (IS) (grossly equivalent to a complete cytogenetic response) is an important response criterion at 1 year or later. In general, BCR-ABL transcripts less than 10% (IS) are equivalent to a partial cytogenetic response with Ph-positive metaphases less than or equal to 35%; and BCR-ABL transcripts less than or equal to 1% (IS) are equivalent to a complete cytogenetic response.31–34 A BCR-ABL transcript of less than or equal to 0.1% (IS) (approximately a 3-log reduction of disease from a standardized baseline) has been associated with a low risk of relapse and with favorable PFS. A negative qPCR analysis (undetectable BCR-ABL transcripts; 4.5-log reduction or more) may be technique dependent and is referred to as a complete molecular response. Monitoring response to imatinib-based therapy may use different approaches depending on the investigators’ experience, whether changes of residual disease affect subsequent therapy, availability of methodologies, and other factors. In general, patients with newly diagnosed CML require an initial bone marrow analysis (to evaluate the percentage of blasts and basophils and whether clonal evolution is present) and then once a year (to detect cytogenetic abnormalities in both the Ph-positive and Ph-negative cell). Some experts recommend bone marrow studies every 3 to 6 months in the first year because of the prognostic significance of the Ph-positive status from routine marrow cytogenetic studies. Practically, peripheral blood FISH studies every 3 to 4 months provide a reasonable estimate of the response profile in the first year. Once Ph-positive cells are 0% by FISH, the complete cytogenetic response can be confirmed by a bone marrow analysis with routine cytogenetics and subsequent monitoring of minimal residual disease performed by peripheral FISH and qPCR studies. If BCR-ABL transcripts are less than 0.1% (IS), qPCR may be used as the single monitoring procedure. The simultaneous use of FISH and qPCR allows for verification of concordance of results in patients who are in complete cytogenetic response but not in major molecular response. In a patient in stable complete cytogenetic response, FISH and qPCR studies may be performed every 6 months. If concerns arise regarding changes in qPCR values, the study can be repeated more frequently (e.g., every 3 months). Some investigators suggest a twofold or 0.5-log increase in transcript levels may correlate with the development of mutations or with relapse.30,31 However, these analyses stem from individual laboratories with significant expertise and may not apply to routine practice. In general, in a patient in complete cytogenetic response, an increase of BCR-ABL transcripts should be confirmed before a change of therapy is considered, if at all. Significant fluctuations in BCR-ABL transcripts may also suggest poor treatment compliance and require discussions with the patient regarding compliance with TKI therapy. Among patients receiving frontline imatinib therapy, an optimal response requires achievement at least a partial cytogenetic response (Ph-positive metaphases ≤ 35%) by 6 months of therapy and a complete cytogenetic response by 1 year of therapy. Recent studies have suggested that, with qPCR, an optimal response would be a reduction of the BCR-ABL transcripts to less than or equal to 10% (IS) at 3 to 6 months and to less than or equal to 1% (IS) after 1 year of therapy. Failure to achieve BCR-ABL transcripts of less than or equal to 10% (IS) or a partial cytogenetic response at 3 to 6 months, and failure to achieve and maintain a complete cytogenetic response beyond 1 year of imatinib therapy, indicate a worse prognosis. It has not been established yet whether a change of therapy at the early time points (3 to 6 months) improves outcome.34–34 When second-generation TKIs (e.g., nilotinib, dasatinib) are used as frontline therapy, earlier responses are expected.35 An optimal response is considered to be achievement of complete cytogenetic response after 3 to 6 months of therapy. Patients not in complete cytogenetic response by that time have a worse event-free survival, but their survival is still excellent (estimated 3-year survival > 90%),35 therefore precluding the need to consider allogeneic SCT in this minority of patients (5% to 10% of total population) but advising closer observation to identify early patients who may require a change of therapy (e.g., to newer-generation TKIs such as ponatinib or allogeneic SCT).

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

Introduction

Incidence, Epidemiology, and Etiology

Pathogenesis

Molecular Pathogenesis

Animal Models of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

Clinical Presentation

Chronic Phase

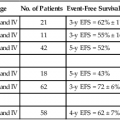

Parameter

Percentage

Age ≥ 60 years (median)

18 (46)

Female gender

41

Splenomegaly

32

Hepatomegaly

5

Lymphadenopathy

5

Other extramedullary disease

2

Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL

12

Platelets

>450 × 109 cells/L

31

<100 × 109 cells/L

3

WBC ≥ 50 × 109 cells/L

38

Marrow

≥5% blasts

6

≥5% basophils

14

Peripheral blood

≥3% blasts

9

≥7% basophils

10

Cytogenetic clonal evolution other than the Philadelphia chromosome

4

Sokal risk

Low

62

Intermediate

27

High

10

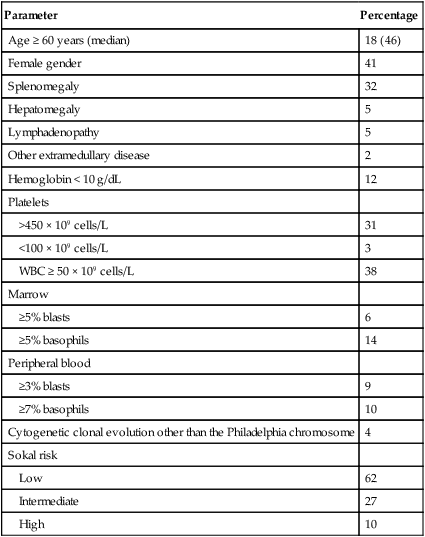

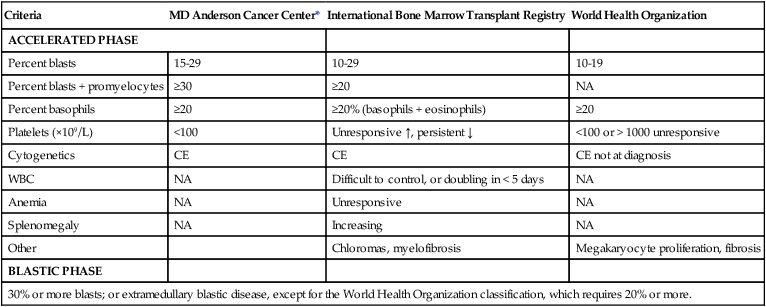

Accelerated and Blastic Phases

Criteria

MD Anderson Cancer Center*

International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry

World Health Organization

ACCELERATED PHASE

Percent blasts

15-29

10-29

10-19

Percent blasts + promyelocytes

≥30

≥20

NA

Percent basophils

≥20

≥20% (basophils + eosinophils)

≥20

Platelets (×109/L)

<100

Unresponsive ↑, persistent ↓

<100 or > 1000 unresponsive

Cytogenetics

CE

CE

CE not at diagnosis

WBC

NA

Difficult to control, or doubling in < 5 days

NA

Anemia

NA

Unresponsive

NA

Splenomegaly

NA

Increasing

NA

Other

Chloromas, myelofibrosis

Megakaryocyte proliferation, fibrosis

BLASTIC PHASE

30% or more blasts; or extramedullary blastic disease, except for the World Health Organization classification, which requires 20% or more.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic and Monitoring Procedures

Important Landmarks for Response or Failure to TKI Therapy

Oncohema Key

Fastest Oncology & Hematology Insight Engine