with indication of high risk by a score >87 and low risk by a score ≤87. Indirectly, the analysis proved that advanced age did not represent an adverse prognostic factor in the TKI era [9].

Interferon Alpha in Elderly Patients

To assess the long-term outcome of older patients with BCR-ABL positive CML, 199 patients aged ≥60 years representing 23 % of 856 patients enrolled in the German randomized CML-studies I (interferon alpha (IFN) vs hydroxyurea (HU) vs busulfan and II (IFN + HU vs HU alone) were analyzed after a median observation time of 7 years. The 5-year survival was 38 % in older and 47 % in younger patients (P < 0.001). Adverse effects of IFN were similar in both age groups, but IFN dosage to achieve treatment goals was lower in older patients [10].

The MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) reported the experience of IFN therapy in CML patients ≥60 years. Patients were treated with IFN at a median dose of 5*106/m2 MU as single agent or in association with other substances. Older patients represented 13 % of an overall population of 274 newly diagnosed patients enrolled in trials. With IFN therapy, 51 % had a cytogenetic response with 20 % of CCyR. These results were not different from those reported in the younger population. The most frequent side effect reported was neurotoxicity in 31 % of patients [11]. In 1998, the Austrian group reported efficacy and safety data relating 41 elderly patients treated with IFN at daily dose of 3.5 MU, alone or in combination with low dose cytarabine [12]. Slight difference was reported between elderly and younger patients in terms of CCyR (10 % vs 13 %), but this was not statistically significant.

The Effect of Imatinib in Older Late Chronic Phase Patients

The first extended analysis on efficacy and safety of imatinib in older patients aged >60 years was reported by Cortes et al. of the MDACC [4]; 187 patients with newly diagnosed CML treated with imatinib first line, of whom 49 (26 %) were in the older age, were compared with 351 patients in late chronic phase after IFN failure, of whom 120 (34 %) were older than 60 years. The cut-off of 60 years was chosen because this limit was identified to be of prognostic relevance in previous multivariate analysis performed in CML cases, but also because patients aged more than 60 years were usually ineligible for transplant procedures and had also poor tolerance to IFN therapy. In early chronic phase, cytogenetic responses were similar to those of younger patients. Only two of the elderly patients were reported to suffer from transformation to advanced phases of disease compared to 5 in the younger subset. In late chronic phase patients, 120 were older (34 %), with a lower incidence of additional chromosome abnormalities compared to younger subjects, more frequent leukocytosis and bone marrow basophilia. 44 % of older patients achieved a CCyR compared to 56 % in younger patients. In multivariate analysis for predicting factors for survival, older age was in chronic and advanced disease not associated to poor outcome.

Rosti et al. reported for the GIMEMA group on 284 patients in late chronic phase CML treated with imatinib 400 mg/day. CCyR rates were lower in older patients (≥65 years) than in younger patients (<65 years) with more adverse events in older patients, but nevertheless overall survival was the same in both age groups [5]. The MDACC and the GIMEMA reports both demonstrated that the poor prognostic impact of older age was minimized by imatinib [13].

Imatinib in Newly Diagnosed Untreated Elderly Patients

Gugliotta et al. reported similar rates of CCyR and MMR in 115 patients ≥65 years among 559 patients in early CP treated with imatinib 400 or 800 mg/day. No relevant differences were observed between older and younger patients except for hemoglobin level, WBC count (median 42/nl in elderly vs 61/nl in younger) and spleen size [14].

In a multicenter study of high-dose imatinib in 115 newly diagnosed patients in chronic phase Cortes et al. reported a similar dose-intensity and no difference in adverse events at any severity for patients <65 and ≥65 years. MMR was achieved by 79 % of patients who received at least 90 % dose-intensity (RIGHT study, [15]). Latagliata et al. analyzed 117 patients in early chronic phase CML under imatinib treatment with 300–800 mg/day. No significant difference in the rate of CCyR was reported in older (≥65 years) compared to younger (<65 years) patients. Adverse events (WHO grades 3–4) were more frequent and rates of dose reduction and discontinuation of imatinib were higher in older patients [16]. Recently, the Spanish group reported the results of the observational ELDERGLI study [17]: patients age was >70 years with newly diagnosed chronic phase CML or >65 years in late chronic phase. Thirty-six patients were included with a median age of 76.6 years and a female predominance. Most frequent comorbidities reported were cardiovascular events and type II diabetes mellitus. After a median follow up of 24 months, increasing response rates were observed, with 83 % CCyR and 69 % MMR after 18 months. Only one patient progressed to blast crisis. Hematological toxicity recorded was moderate with overall 8 % anemia and thrombocytopenia and 11 % neutropenia of all grades. Most frequent non-hematological side effects were superficial edema that accounted for 44 % (grade 1/2), diarrhea (27.7 %), and infections (25 %), which caused death in two patients. The group considered imatinib a safe and effective drug also for older patients.

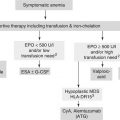

Strategies to Overcome Resistance in Older Patients

Few data were reported for older patients rescued with nilotinib or dasatinib after resistance or intolerance to imatinib. A subanalysis of a phase II trial with nilotinib at the dose of 400 mg BID reported on 98 patients out of 321 enrolled older patients >65 years with 8 % of these patients being >80 years of age. Baseline features were similar between younger and older patients. The rate of discontinuation was 18 %, whereas the CCyR rate was 38 % compared to 44 % in younger patients. One-year estimated overall survival was 91 % for older versus 97 % for younger patients. Similar frequencies of side effects were reported in older and younger patients: in particular, as regards biochemical abnormalities, 23 % of older patients experienced lipase elevation compared to 14 % of younger patients, while 3 % of older patients experienced total bilirubin increase compared to 9 % for younger patients. No particular differences were revealed between the age groups in terms of hematological side effects and in terms of pleuro/pericardial effusions or bleeding events. 4 % of older patients had a myocardial infarction compared to 1 % in younger patients. For the QT interval according to Fridericia formula (QTcF), prolongation higher than 500 ms was recorded in 2 % of older compared to 1 % in younger patients [18].

The expanding nilotinib access study (ENACT, [19]) enrolled 1,422 CP-CML imatinib resistant and/or intolerant patients, of whom 452 patients were aged >60 years and 165 of these were >70 years old. A higher proportion of patients aged >65 years enrolled had a longer median duration of CML and most of them were enrolled for intolerance. The results showed that about 50 % of patients aged >65 years experienced nilotinib dose interruptions and reductions due to side effects lasting more than 5 days. In this trial, 41 % of older patients achieved MCyR with 31 % achieving CCyR (33 % of elderly >70 years). In terms of safety, 56 % of older patients experienced grade 3/4 toxicity, most frequently hematological (thrombocytopenia 24 % and neutropenia 14 %). Patients who had experienced pleural effusion during dasatinib treatment did not have a recurrence of the same effect during nilotinib treatment.

Recently, a retrospective Italian analysis on 125 CP-CML patients resistant to imatinib aged >60 years was published [20]. Median age at the start of dasatinib treatment was 69 years, with a high rate of intermediate and high Sokal risk strata. Fifty-seven patients were pretreated and resistant to IFN before imatinib. Fifty-eight patients had received high-dose imatinib for resistance to the standard dose. Thirteen patients were treated with dasatinib for intolerance and 112 for resistance. The starting daily dose of dasatinib was 140 mg in 52 patients, 100 mg in 56 patients, and <100 mg in 17 patients. As to efficacy, 60 reached CCyR as best response. Four-year OS was 84.2 %. Thirty-one percent of patients experienced grade 3/4 hematological toxicity, mostly in the group of patients treated with 140 mg/day. Twenty-seven percent of patients experienced nonhematological toxicity, with no difference in the rate of events between patients treated with different dosage and schedule. Forty-one patients experienced pleuro/pericardial effusion that was of grade 3/4 in 8 % of patients, with higher frequency in the group of patients treated with 140 mg/day. Due to toxicity, 67 patients required a dose reduction and 19 patients needed permanent discontinuation. This real-life experience showed that dasatinib could be safely used in older patients.

A subanalysis of 119 patients aged >65 years treated with bosutinib was presented in 2012 and a comparison was made with 451 younger patients [21]. Bosutinib was administered at a dose of 500 mg/day. Bosutinib was discontinued in 80 % of patients over 65 years of age compared to 67 % of younger patients, in 32 % of cases being due to adverse events, mostly thrombocytopenia. Rate of treatment transformation, incidence of hematological side effects and the incidence of diarrhea were similar between patients older or younger than 65 years.

Recently, a 3rd-generation inhibitor was tested in resistant CML patients: ponatinib is a potent, oral inhibitor able to block native and mutated BCR-ABL, including T315I mutation, which are resistant to dasatinib and nilotinib. The phase II “Ponatinib Ph + ALL and CML Evaluation” (PACE) trial tested ponatinib 45 mg QD in 449 patients (median age 59 years; range 18–94) resistant or intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib or with the T315I mutation in different phases of disease. In chronic phase patients, 46 % achieved a CCyR and 32 % MMR with 12 % MR4.5 (BCR-ABL IS ≤0.0032 %). Similar responses were obtained in patients with or without mutations, with a higher rate in patients with the T315I mutation. However, 20 % of arterial and venous thrombotic events prompted a revision of the treatment recommendations with a lower dose recommended in good responders and precautions regarding vascular events [22].

Second Generation TKIs in First Line Use in Older Patients

The DASISION trial (Dasatinib versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naïve CP-CML patients) was a large phase III trial comparing dasatinib 100 mg BID versus imatinib 400 mg QD in newly diagnosed patients. A subanalysis of the study showed efficacy and safety results according to baseline comorbidity and age. In the dasatinib arm, CCyR rates were 88 % for patients aged <46 years, 78 % for those aged 46–65 years, and 85 % for those aged >65 years; the corresponding MMR rates were 45, 47, and 50 %, respectively. In the imatinib arm, CCyR rates of 70, 70, and 83 % were reported for patients <46 years, 46–65 years, and >65 years, respectively; MMR rates were 26, 30, and 29 %, respectively. Safety profiles were similar across all age groups in both treatment arms, except for fluid retention rates observed in the dasatinib arm (13, 25, and 35 %) compared to the imatinib arm (34, 45, and 67 %) for patients aged <46, 46–65, and >65 years, respectively [23].

The ENESTnd trial (Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials of Newly Diagnosed Ph + CML Patients) is a phase III trial testing two different doses of nilotinib (300 and 400 mg BID) versus the standard dose of imatinib (400 mg QD). In this trial, 36 patients (13 %) and 28 patients (10 %) were >65 years old in the 300 and 400 mg BID nilotinib arms, respectively. Efficacy was maintained in older patients, with an MMR rate of 78 % in the nilotinib 300 mg BID arm and a MR4.5 rate of 31 %. CCyR rates by 24 months were 83 and 68 % among older patients treated with nilotinib 300 and 400 mg, respectively, compared to 87 % in younger patients in either of the nilotinib arms. 72 and 61 % of older patients achieved MMR, respectively, whereas in younger patients, the respective rates were 71 and 67 %. As regards safety, no patients had grade 3/4 neutropenia and only one older patient reported grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia in each nilotinib arm. Transient, asymptomatic lipase elevations occurred in 11 and 16 % of older patients treated with nilotinib 300 and 400 mg, and in 7 % of younger patients in each arm. Hyperglycemia occurred in 23 and 16 % of patients aged over 65 years on nilotinib 300 and 400 mg, respectively, and in 4 % of younger patients in either arm. Overall, the primary endpoint (MMR within 12 months) was maintained in the nilotinib 300 mg BID arm at 4-year follow-up with an MMR rate of 76 versus 56 % for imatinib; the MR4 rates were 56 and 32 % and the MR4.5 rates were 40 and 23 %. Statistically significant reduction of progression rate was observed in the nilotinib 300 mg BID arm (0.7 %) as compared to imatinib (4.2 %) [24].

Bosutinib was tested in a phase III randomized trial in first line versus imatinib standard dose (BELA trial). A subanalysis in older patients enrolled in the BELA trial was presented: 30 patients were treated with bosutinib and 27 with imatinib. None of the patients aged >65 years treated with bosutinib progressed. Among patients aged >65 years, grade 3/4 events were more frequently recorded (gastrointestinal events, elevated transaminases, pyrexia); 64 % of this subset required dose reduction, and 39 % required treatment discontinuation due to side effects [25]. Overall, the study did not achieve the primary endpoint (rate of CCyR) because at 12 months there was no difference between the two arms (70 % for bosutinib vs 68 % for imatinib). Despite these results, the MMR rate improved in the bosutinib arm (41 vs 21 % for imatinib arm) and responses were achieved faster with this inhibitor. Consequently, only 2 % of patients progressed to advanced phases of disease as compared to 4 % in the imatinib arm.

All studies clearly showed that efficacy was similar for the three different inhibitors tested as frontline treatment, even in patients aged >65 years, but with a specific safety profile for each one which should be carefully evaluated according to the presence of concomitant comorbidities [26].

Pharmacokinetics

For all patients, potential drug-drug interactions are a concern when multiple medications are taken, and elderly patients are more likely than younger patients to be on a multiple medication regimen. For patients aged >65 years, 90 % are taking at least one prescription drug, and 65 % are taking at least 3 prescription drugs, compared with 65 and 34 % of patients aged 45 to 64 years, respectively. All TKIs are metabolized in a similar fashion, primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 (CYP3A4), a liver enzyme that is active in the metabolism of many other drugs. Other CYP enzymes and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase appear to play a minor role. Clinical recommendations for the use of TKIs with other medications, therefore, largely involve concomitant use of agents (including food, vitamins, or supplements) that are strong inducers or inhibitors of CYP3A4 or are substrates of CYP3A4. Further, the prescribing information for TKIs provides guidance for the concomitant use of antiarrhythmics or agents that prolong QTc and for the concomitant use of cumulative high-dose anthracyclines [27].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree