PATIENT NAME:_____________ DATE:_________ TIME (24hr):_________ |

Birthdate (mm): (dd): (yyyy): |

Sex: [ ] Male [ ] Female Enter education (years): |

Race: [ ] Caucasian [ ] Black [ ] Hispanic [ ] Asian [ ] Other |

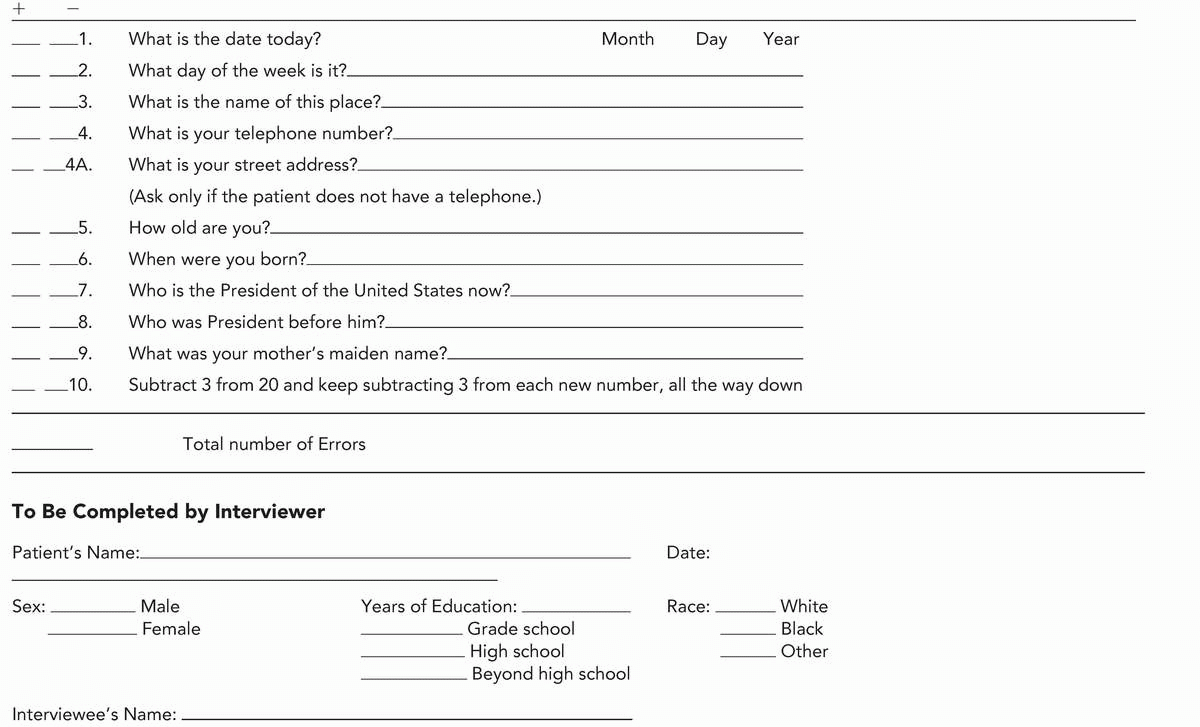

Orientation Questions: Ask the following questions: |

right/wrong |

[ ] [ ] 1. What is today’s date? |

[ ] [ ] 2. What is the month? |

[ ] [ ] 3. What is the year? |

[ ] [ ] 4. What day of the week is today? |

[ ] [ ] 5. What season is it? |

DATE |

[ ] [ ] 6. What is the name of this clinic (place)? |

[ ] [ ] 7. What floor are we on? |

[ ] [ ] 8. What city are we in? |

[ ] [ ] 9. What county are we in? |

[ ] [ ] 10. What state are we in? |

PLACE |

IMMEDIATE RECALL: Ask the subject if you may test his/her memory. Then say “ball”, “flag”, “tree” clearly and slowly, about 1 second for each. After you have said all 3 words, ask him/her to repeat them. The first repetition determines the score (0-3), but keep saying them until he/she can repeat all 3, up to 6 tries. If he/she does not eventually learn all 3, recall cannot be meaningfully tested: |

[ ] [ ] 11. BALL |

[ ] [ ] 12. FLAG |

[ ] [ ] 13. TREE |

Note # trials: |

IMMEDIATE RECALL: |

ATTENTION |

A) Ask the subject to begin with 100 and count backwards by 7. Stop after 5 subtractions. Score the correct subtractions. |

[ ] [ ] 14. “93” |

[ ] [ ] 15. “86” |

[ ] [ ] 16. “79” |

[ ] [ ] 17. “72” |

[ ] [ ] 18. “65” |

SERIAL 7’s TOTAL: |

B) Ask the subject to spell the word “WORLD” backwards. The score is the number of letters in correct position. For example, “DLROW” is 5, “DLORW” is 3, “LROWD” is 0. |

[ ] [ ] 19. “D” |

[ ] [ ] 20. “L” |

[ ] [ ] 21. “R” |

[ ] [ ] 22. “O” |

[ ] [ ] 23. “W” |

“DLROW” TOTAL: |

Greater score of A or B: |

DELAYED VERBAL RECALL: Ask the subject to recall the 3 words you previously asked him/her to remember. |

[ ] [ ] 24. BALL? |

[ ] [ ] 25. FLAG? |

[ ] [ ] 26. TREE? |

DELAYED VERBAL RECALL: |

NAMING: Show the subject a wrist watch and ask him/her what it is. Repeat for pencil. |

[ ] [ ] 27. WATCH |

[ ] [ ] 28. PENCIL |

[ ] [ ] 29. REPETITION (Ask patient to repeat items in 24, 25 and 26) |

3-STAGE COMMAND: Give the subject a plain piece of paper and say, “Take the paper in your hand, fold it in half, and put it on the floor.” |

[ ] [ ] 30. TAKES |

[ ] [ ] 31. FOLDS |

[ ] [ ] 32. PUTS |

READING: Hold up a card reading, “Close your eyes”, so the subject can see it clearly. Ask him/her to read it and do what it says. Score correctly only if the subject actually closes his/her eyes. |

[ ] [ ] 33. CLOSES EYES |

WRITING: Give subject a piece of paper and ask him/her to write a sentence. It is to be written spontaneously. It must contain a subject and verb and be sensible. Correct grammar and punctuation are not necessary. |

[ ] [ ] 34. SENTENCE LANGUAGE: |

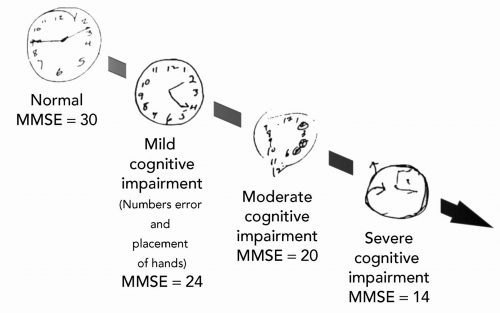

[ ] [ ] 35. DRAW PENTAGONS |

TOTAL MMSE:_______________ |

(MMSE maximum score = 30; 24-30 normal, depending on age, education, complaints; 20-23 mild; 10-19 moderate; 1-9 severe; 0 profound.) |

MEDAFILE.COM |

(calculation derived from Ashford et al., 1995; Mendiondo et al., 2000) |

(forms are in public domain; HTML scripted by Ashford, JW, copyright 2000) |