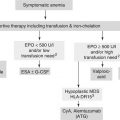

Fig. 7.1

Age-distribution among patients with newly diagnosed CLL

Biology and Aging

The etiology of CLL is unknown and its pathogenesis is not fully understood [2]. The reason why CLL predominantly develops at an advanced age also is not clarified. Long-lasting antigen stimulation, accumulation of genomic events, and age-related changes in immunosurveillance or microenvironment potentially play a role. In some but not in all older patients, monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis (MBL) precedes CLL for many years [3].

There is no sound evidence that the clinical behaviour of CLL is significantly different in younger and older patients. At any age, CLL could stay an indolent disease for decades. Conversely, aggressive disease courses with early need of therapy and refractoriness to conventional treatment are similarly observed in both younger and older CLL patients.

Patient Heterogeneity

While biology of the disease (e.g., deletion of the short arm of the chromosome 17 or loss of the tumor suppressor p53) determines the course of the disease, CLL-unrelated though age-related changes in the host could also influence the course of CLL. Such hallmarks of aging are physiological decline of organ function (e.g., decrease in glomerular filtration rate, decrease in regenerative capacity of tissues) and pathological occurrence of comorbidities (particularly cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and musculoskeletal diseases) that ultimately could result in the inability to manage activities of daily living, and dependency. However, these age-related changes are highly variable among individuals. Therefore, great heterogeneity is observed among older CLL patients with regard to functional organ reserve, presence of comorbidity, geriatric syndromes, disability, and dependency. For instance, severe comorbidities (i.e., cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, other malignancy) are found in 46 % of unselected patients with newly diagnosed CLL while the remaining 54 % are either free of comorbidity (11 %) or affected with milder comorbidities (43 %, e.g. hypertension, hyperlipemia, arthritis, peptic ulcer) [4]. In another observational study of 8,343 newly diagnosed CLL patients > 65 years, comorbidity was found in 45 % of the untreated CLL patients and 38 % of the treated CLL patients [5]. To date, there are no descriptive data on frequencies of geriatric syndromes (e.g., polymedication, falls, sarcopenia, dementia, delirium, depression, incontinence), disability, or dependency in older CLL patients. So far, such numbers can only be roughly extrapolated from data obtained from studies in the community-dwelling population of elderly people.

Patient Vulnerability

There is growing evidence that in older CLL patients decline of organ function and increase of comorbidity have impact on treatment tolerability and efficacy. For instance, renal impairment (reflected by a reduction in creatinine clearance) but not age is associated with greater risk of hematological toxicity upon treatment with the purine analogue fludarabine [6]. Increased comorbidity measured by Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) has been shown to predict toxicity of combined chemotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy administered to CLL patients [7]. Higher comorbidity burden prior to treatment has also been demonstrated to be an age-independent predictor of overall survival (OS) of CLL patients [7, 8]. Underlying mechanisms are probably complex since comorbidity could affect OS of older CLL patients in multiple ways: Firstly, diseases other than CLL may cause earlier death of comorbid CLL patients. Secondly, comorbidity may facilitate occurrence of fatal treatment toxicity or make it more difficult to control adverse treatment events, hence resulting in more treatment-related deaths. Thirdly, comorbidity might enforce treating physicians to reduce the treatment dose or to interrupt therapy due to intercurrent disease, thereby limiting the treatment’s benefit and offsetting control of CLL which then could result in earlier death due to CLL. Indeed, CLL-unrelated deaths, toxicity-related deaths, and CLL-related deaths all are contributors of higher mortality in comorbid CLL patients compared to more healthy subjects with CLL [9]. Potentially, characteristics of aging other than comorbidity (i.e. geriatric syndromes, disability, dependency) also have impact on treatment tolerability and survival in older CLL patients, but CLL-specific data are still lacking.

Diagnostic Options and Outcomes

Blood count including differential, blood smear microscopy, immunophenotyping, and physical examination (palpation of lymph nodes, spleen and liver) are mandatory to establish the diagnosis and to stage CLL [10, 11]. Bone marrow aspiration or biopsy is not needed to diagnose CLL and therefore is optional. All of the following diagnostic criteria must be fulfilled for establishing the diagnosis: Lymphocytosis > 5 G/L, microscopic detection of small mature lymphocytes, and a typical CLL immunophenotype (CD19+, CD20+, CD5+, CD23+). The Binet and Rai classifications are used for disease staging. Imaging could help to further quantify the extend of lymphadenopathy and organomegaly, but is not mandatory in routine practice and may put older patients at increased risk to develop renal failure if kidney function is impaired. Molecular staging could include the assessment of prognostic factors like thymidine kinase, ß2 microglobulin, ZAP70, CD38, IGHV mutational status, or FISH cytogenetics to predict time to disease progression in early-stage CLL or responsiveness to treatment in advanced-stage CLL. However, the predictive impact of such factors could differ significantly in younger and older CLL patients. In a survey of 2,487 patients diagnosed with CLL, IGHV and FISH predicted survival in younger patients (55–74 years), but failed to be prognostic in patients who were 75 years old or older [12]. In another study, expression of the CLL-specific gene CLLU1 was prognostic in CLL patients younger than 70 years, but had no prognostic impact in patients aged 70 years or older [13]. Deletion of 17p or lack or p53 function remains a significant adverse factor across age groups.

Patients above the age of 75 years with early-stage CLL were found to live as long as the age-matched general population [12]. Therefore, older patients diagnosed with CLL at an early stage (i.e., asymptomatic Binet stage A or B) usually are not in need of treatment and many of them will have indolent CLL for years [14]. For both younger and older CLL patients, treatment of CLL is indicated if signs of bone marrow failure (i.e. Binet C), severe B-symptoms (i.e., weight loss, fever, night sweats), general fatigue, symptomatic lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, short lymphocyte doubling time, or autoimmune disorders are present [10, 11].

Additional Assessments

Treatment decisions in older CLL patients are guided by disease characteristics (i.e. detection of deletion 17p) and patient fitness (i.e. vulnerability). In principle, there are several approaches to assess patient fitness and vulnerability:

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) or use of specific scoring systems that include elements of CGA has been shown to predict toxicity and survival in older tumor patients [15–17]. However, evidence from prospective studies demonstrating that performance of a CGA in tumor patients prior to treatment will improve outcome is still very sparse. Importantly, such approach has not yet been validated in CLL. Neither it is known whether the assessment of single geriatric syndromes (e.g., polymedication, falls, loss of cognition, depression, incontinence), disability, or dependency, or whether apparatus investigations (e.g., echocardiography, stress electrocardiography) improve outcome of older CLL patients.

In contrast, comorbidity is known to be associated with treatment toxicity and reduced overall survival in older CLL patients [4, 5, 7, 8]. In clinical trials, mainly CIRS has been used to select for comorbid CLL patients and to allocate those to specific treatments although validation of the cut-offs used (e.g., total CIRS score of 6) is still incomplete.

Therapeutic Options and Outcomes

The spectrum of therapeutic options for older CLL patients is broad and ranges from intense chemoimmunotherapy to best supportive care (reviewed in [18]). In selected older patients, even allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) could be a reasonable treatment approach. While many of the possible treatments are approved in Europe and North America, some are still experimental and currently explored in clinical trials only (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1

Therapeutic options in older patients with CLL

Regimen | Evidence | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

FCR | Phase 3 trial (subgroup analysis), phase 2 trials | Equally toxic than in younger patients if patients are carefully selected for low burden of comorbidity, significant toxicity in unselected older patients. |

PCR | Phase 2 trial (subgroup analysis) | Equally toxic than in younger patients if patients are carefully selected. |

FCR low-dose | Phase 2 trials | Feasible in older patients with low to moderate burden of comorbidity. |

FC | Phase 3 trial (subgroup analysis), phase 2 trial | Superior to CLB and F, no data for comorbid older patients, significant toxicity. |

FC low-dose | Phase 2 trial | Well tolerated, but little data in comorbid older patients. |

F | Phase 3 trial, phase 3 trial (subgroup analysis), phase 2 trial | Not superior to CLB, more toxic than CLB. |

F low-dose | Phase 2 trial | Well tolerated, but shortened PFS. |

BR | Phase 3 trial (preliminary results) | Feasible in older patients, role in comorbid older patients still unclear. |

B | Phase 3 trial (subgroup analysis) | Superior to CLB, but more toxic than CLB, no data for comorbid older patients. |

CLB-R | Phase 2 trial | Well tolerated, more remissions than in historical controls treated with CLB alone. |

CLB | Phase 3 trial | Not inferior to F, less toxic than F. |

G | Phase 3 run-in trial | Feasible in older patients, not yet approved. |

O | – | No data available, not yet approved. |

CAM | – | Feasible in high-risk older patients, not approved. |

LEN | Phase 2 trial | Feasible in older patients, not yet approved |

Ibrutinib | Phase 1/2 trial | Feasible in older patients, promising efficacy, not yet approved. |

Idelalisib | – | Role in older patients unclear, not yet approved. |

Fludarabine-Based Therapy

Chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) is the standard of care in younger and physically fit CLL patients [19]. Complete remissions (CR) are achieved in 44 % of the patients and the median progression-free survival (PFS) is 52 months. Importantly, addition of the monoclonal CD20 antibody rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide improves overall survival (OS) in CLL patients. The potential benefits of FCR treatment are coupled with a substantial risk of toxicity, however. Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia occurs in every third patients (34 %) and grade 3 or 4 infections are observed in 25 % of patients treated with FCR. Those patients with high leukocyte counts or bulky lymphadenopathy at baseline are at risk to experience infusion-related reactions (IRR) during or after infusion of rituximab.

In a cohort of previously untreated CLL patients aged 70 years or older, use of FCR was associated with significant toxicity, frequent withdrawal from treatment, and early death [20]. Moreover, FCR treatment in older CLL patients was less efficacious than in younger CLL patients [21]. In the CLL8 trial of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG), there was no significant difference between younger patients (30–69 years) and older patients (70–80 years) treated with FCR, however. A treatment benefit was demonstrated across all age groups. Likewise, no difference in toxicity or efficacy was observed between younger and older patients in a trial investigating chemoimmunotherapy with pentostatin, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (PCR), a regimen that compares well with FCR [22]. Of note, patients in both trials had none or only mild comorbidity. It therefore can be concluded from these findings that full-dose purine analogue-based chemoimmunotherapy is feasible and beneficial in the subset of older CLL patients who are physically fit and have no major concurrent diseases.

With the goal to reduce toxicity but to keep efficacy, low-dose schedules of FCR have been proposed for older patients. A first study investigating a ‘FCR lite’ regimen reported impressive response rates (77 % CR), but less convincing durations of remissions (22 months) [23]. Importantly, this study was conducted in younger and not in older CLL patients (median age: 58 years). Meanwhile, first results from studies of low-dose FCR in significantly older CLL patients have been made available. In one trial in 169 patients (median age: 69 years, median total CIRS score: 5), response to treatment, grade 3–4 neutropenia and infection were observed in 81, 53 and 10 %, respectively [24]. In an Australian trial (120 patients, median age: 72 years, total CIRS score 0–6), 92 % of the patients responded to treatment and 30 % had grade 3–4 neutropenia [25]. A French study (200 patients, median age: 71 years, total CIRS score 0–6) reported a response rate of 96 % with use of G-CSF in more than half of the patients due to neutropenia [26]. FCR schedules in the three trials varied. Taken together, low-dose FCR is a treatment option in older CLL patients. Since the comorbidity burden in these phase 2 trials were relatively low, however, it is difficult to judge whether the risk-benefit ratio of this regimen will still be favorable in older CLL patients with significantly increased comorbidity. Furthermore, one has to keep in mind that so far no phase 3 trial evidence for these regimens exists.

Prior to the era of rituximab, low-dose regimens with fludarabine alone or fludarabine in combination with cyclophosphamide were explored in older CLL patients (reviewed in [18]). One phase 3 trial compared standard-dosed fludarabine with chlorambucil in older CLL patients [27]. Surprisingly and in contrast to a trial conducted in younger CLL patients, this trial failed to demonstrate superiority of fludarabine over chlorambucil in this patient population. Lack of benefit from fludarabine compared to chlorambucil treatment in older CLL patients was also observed in another large phase 3 trial [28].

Bendamustine-Based Therapy

Bendamustine is a bifunctional agent that carries a nitrogen-mustard group with alkylating properties. In a trial of previously untreated CLL patients, bendamustine was shown to be more efficacious than chlorambucil. Younger patients (35–65 years) and older patients (66–78 years) benefitted equally from the treatment with bendamustine, but the total number of enrolled patients of significantly advanced age (70 years or older) was small and the comorbidity burden of the patients was not reported [29]. Although bendamustine is frequently and often successfully used in clinical practice to treat older CLL patients, robust evidence supporting single-agent use of bendamustine in this patient population is still lacking.

Chemoimmunotherapy with bendamustine and rituximab (BR) has been suggested as a treatment option for older CLL patients. In a cohort of relapsed CLL patients which included patients of advanced age, BR proved to be safe and efficacious [30]. In a preliminary report of a randomized trial comparing BR with chlorambucil plus rituximab (CLB-R) in previously untreated and older CLL patients (median age: 74 years; burden of comorbidity not reported), BR and CLB-R yielded responses in 88 and 81 % of the patients (more CR with BR) and suggested acceptable toxicity in both treatment arms (grade 3–4 neutropenia 32 and 34 %) [31]. It therefore appears reasonable, to further develop BR as a treatment for older CLL patients including those with increased comorbidity. As with low-dose FCR, however, it remains to be determined within future trials what level of fitness and comorbidity in older CLL patients will be acceptable to apply BR in a safe and non-harming way. Final results from the trial comparing BR with CLB-R (MaBLe trial) as well as from a trial evaluating bendamustine plus the CD20 antibody ofatumumab versus chlorambucil plus ofatumumab (RIAltO trial) hopefully will help to better answer this question.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree