Chronic Disease Management: Introduction

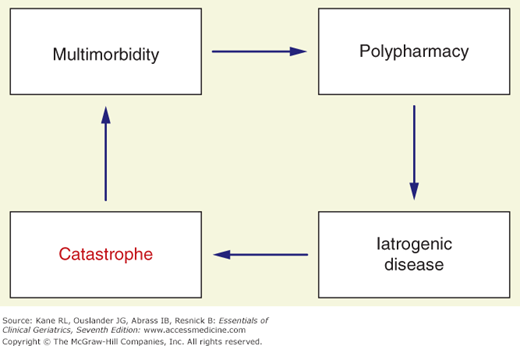

Geriatrics can be thought of as the intersection of gerontology and chronic disease management (Kane, Priester, and Totten, 2005). At a time when medical care in general is awakening to the importance of good chronic disease care, geriatrics has been doing it for years. Many of the principles of geriatrics are basically those of good chronic care. Chronic disease management has two basic components. The first aims at preventing catastrophes (ie, emergency room visits and hospitalizations) by proactively monitoring patients’ conditions and intervening at the first sign of a change in the clinical course. Ideally these interventions prevent some hospitalizations, primarily by providing more effective primary care that prevents the event, but secondarily by managing crises, when they occur, without hospitalization. Figure 4-1 illustrates the paths to chronic disease catastrophe. Multimorbidity is associated with polypharmacy, which, in turn, can lead to iatrogenic complications. The second basic component is palliative care. We tend to associate this type of care with end-of-life care, but its principles can be applied much more broadly.

Several models of chronic disease management have been promulgated. The most popular is the Wagner model, which envisions a productive interaction between an informed, activated patient (and caregiver) and a prepared, proactive practice team (Wagner, Austin, and Von Korff, 1996). Unfortunately the current health-care system is poorly organized to facilitate such care. Fee-for-service payments, driven by in-person encounters, provide exactly the wrong climate for proactive care that uses modern communication technology to track patient status. The basic tenets of good chronic care are summarized in Table 4–1.

Aggressive primary care |

Proactive monitoring |

Early intervention to avoid catastrophes |

Patient-centeredness, meaningful patient involvement in the care process |

Use of information technology to track outcomes and trigger reevaluation |

Teamwork, delegation |

Efficient use of time |

Assessing benefit in terms of slowing decline |

Elderly patients are in danger of being dismissed as hopeless or not worth the effort based on their age. Physicians faced with the question of how much time and resources to spend in searching for a diagnosis will want to consider the probability of benefit from the investment. In some cases, older patients are better investments than younger ones. This apparent paradox occurs in the case of some preventive strategies when the high risk of susceptibility and the discounted benefits of future health favor older persons. But it also arises in situations where small increments of change can yield dramatic differences.

Perhaps the most striking example of the latter is found in the case of nursing home patients. Ironically, very modest changes in their routine, such as introducing a pet, giving them a plant to tend, or increasing their sense of control over their environment, can produce dramatic improvements in mood and morale.

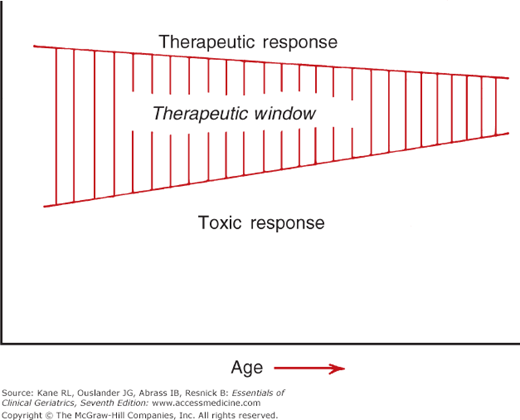

At the same time, the risk–benefit ratio is different with older patients. Treatments that might be easily tolerated in younger patients may pose a much greater risk of producing harmful effects in older patients with multiple chronic illnesses. As shown in Figure 4-2, the therapeutic window that separates benefit from harm is narrower. In effect, the dosage that will produce a positive effect more closely approaches one that can lead to a toxic effect. As noted earlier in this text, one of the hallmarks of aging is a loss of responsiveness to stress. In this context, treatment may be viewed as a stress.

Those who treat older patients must also consider the theory of competitive risks. Because older persons often suffer from multiple problems, treating one problem may provide an opportunity for more adverse effects from another. In essence, eliminating one cause of death increases the likelihood of death from other causes.

System Changes

Professional roles need to be reexamined to look for opportunities to delegate to less expensive personnel many tasks formerly performed by more trained professionals. For example, nurse practitioners have been shown to be capable of providing a good deal of primary care that was formerly the exclusive purview of physicians (Horrocks, Anderson, and Salisbury, 2002; Mundinger et al., 2000). New models of collaborative care seem promising (Callahan et al., 2006; Counsell et al., 2006).

The enthusiasm for teams needs to be tempered by an appreciation of the skills needed to work cooperatively and the willingness to delegate tasks (Kane, Shamliyan, and McCarthy, 2011).

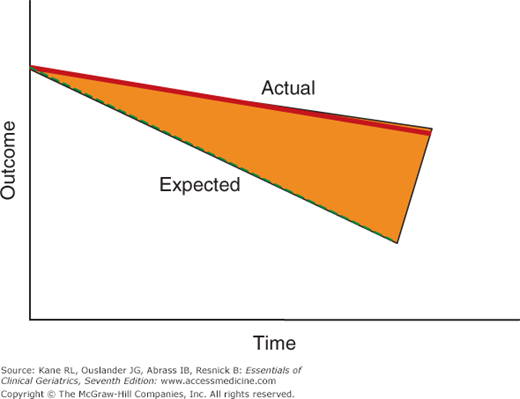

Expectations must be recalibrated. The familiar dichotomy of care versus cure must be expanded to recognize the role of disease management. Because the natural course of chronic illness is deterioration, successful care must be defined as doing better than would be expected otherwise. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 4-3. The bold line represents the effects of good care. The dotted line represents the effects of the absence of such care. Both lines show decline over time. The difference between them represents the effects of good care. Most of the time, this contrast is invisible—all that is seen is decline despite the best efforts. Improving care will require developing information systems that can contrast actual and expected clinical courses.

Figure 4-3

A conceptual model of the difference between expected and actual care. The heavier line represents what is usually observed in clinical chronic care. Despite good care, the patient’s course deteriorates. The true benefit, represented by the area between the dark line and the dotted line, is invisible unless some means is found to display the expected course in the absence of good care. Such data could be developed based on clinical prognosis, or it could be derived from accumulated data once such a system is in place.

Appreciating this contrast is critical to both policy and morale. The importance of measuring success by comparing the actual clinical course to a generated expected course is central to concepts of quality in chronic disease. It is also important in maintaining the morale of workers in this field. People who see only decline despite their best efforts become discouraged (Lerner and Simmons, 1966). They need to appreciate the value of their care if they are to continue to give it in the face of so much frailty and disability. Slowing the rate of decline must be seen as positive achievement.

Likewise policymakers, and indeed the general public, are unlikely to support needed efforts to improve chronic care if they do not believe that such care can make a difference. They must be educated to appreciate these differences and be given the information to demonstrate these differences.

Transitional Care

Transitions from hospitals have been targeted for special attention. Currently, discharges, and other times when care is transferred, represent danger zones. There is great concern about the high rate of rehospitalizations, which represent signs of care failure and add to the costs of care. When medical regimens are changed, the relevant information may be poorly communicated (both between clinicians and with patients and families). Careful coordination and follow-up are associated with lower rates of rehospitalization and lower costs (Coleman et al., 2006; Naylor et al., 1994). Transitional care consists of a set of specific actions.

Prior to discharge, a coach meets with the patient and her family to establish a rapport and assist with discharge planning.

The coach meets with the patient soon after discharge to be sure she understands the discharge plan and is comfortable with her medication regimen and any other instructions.

The coach stays in close contact during the ensuing period to be sure things are going well.

The patient’s primary care physician is urged to get involved soon after discharge and gets all relevant information.

End‐of-Life Care

Eliminating excessive, futile, or unnecessary care and attention to preventing iatrogenic events can improve care and save money. Two ready targets are medications and end-of-life care, including palliative care. Medication management in geriatric patients is discussed in detail in Chapter 14. In addition to the section that follows, end-of-life care is discussed in Chapters 16 and 17.

The physician’s concern with the patient’s functioning continues throughout the course of the chronic disease. Elderly patients will die. In many cases, death is not a reflection of medical failure. The approach to the dying patient will often raise difficult dilemmas. No simple answers suffice. Too often the dying patient is treated as an object. Ignored and isolated, the patient may be discussed in the third person.

Physicians who treat elderly patients must come to terms with death. Often the patients are more comfortable with the subject than are their physicians (and their families). Fleeing from the dying patient is inexcusable. Dying patients need their doctors. At a very basic level, everything should be done to keep the patient as comfortable as possible. One simple step is to identify the pattern of discomforting symptoms and arrange the dosage schedule of palliatives to prevent rather than respond to the symptoms.

Patients need an opportunity to talk about their death. Not everyone will take advantage of that chance, but a surprising number will respond to a genuine offer made without time pressure. Such discussions are not conducted on the run. Often several invitations accompanied by appropriate behavior (eg, sitting down at the bedside) are necessary.

Some physicians are unable to confront this aspect of practice. For them, the challenge is to recognize their own behavior and get appropriate help. Such help is available at various levels: help for the physician and for the patient. Groups and therapy are readily available to assist doctors to deal with their feelings. Patients of doctors who fear death need the help of other caregivers. Often other professionals (nurses, social workers) who are working with these patients already can play the lead role in helping them work through their feelings. But the active intervention of another caregiver is not a justification to ignore the patient.

The rise of the hospice movement has created a growing cadre of persons and settings to help with the dying patient. The lessons coming from this experience suggest that much can be done to facilitate this stage of life, although the formal studies done to evaluate hospice care do not show dramatic benefits.

Patients should be encouraged to be as active as possible and as interactive as they wish. Even more than in other aspects of care, the unique condition of the dying patient necessitates that the physician be prepared to listen carefully to the patient and to share decision making about how and when to do things.

Medical care has evolved in such a way that special exemptions are made for the period at the end of life. Hospice care was created to reverse the overuse of technology and denial of dying (see Chapter 18). It can be viewed as both a success and a failure. On the one hand, it is still probably used too little and too late, only after more drastic measures have been tried. At the same time, it has led to serious reconsideration of how medicine handles the process of dying. It has spawned the concept of palliative care, an idea that many aspects of support and comfort can be applied coincident with active treatment (Morrison and Meier, 2004). It has forced a reassessment of how pain is managed, with more attention to proactive treatment in adequate doses. Palliative care is discussed in detail in Chapter 18.

Special Issues in Chronic Disease Management

Chronic care requires proactive primary care supported by better data systems. The whole approach to care needs to be rethought. The idea of scheduled revisits needs to be replaced with a system of ongoing monitoring and interventions when there is a significant change in the patient’s condition. Information technology is probably the most important technological breakthrough for chronic care.

Structuring data helps to focus the clinician’s attention on what is most relevant. The goal of a good information system should be to present clinicians with pertinent information at the right time in the form that will capture their attention. Identifying what is salient at the moment is critical, especially in view of the brief contact times allowed. Too much information can be as dysfunctional as too little, because the pertinent facts get lost in a sea of data.

Providing effective chronic care that avoids catastrophes relies on a longitudinally oriented information system that is sensitive to change. Each clinical encounter with a chronically ill patient is essentially a part of a continuing episode of care; it has a history and a future. Caring for a chronically ill patient, especially one with multiple problems, demands an enormous feat of memory as the patient’s list of problems is unearthed and the history, treatments, and expectations associated with each are reviewed. Clinicians caring for such patients (often under enormous time pressures) may find themselves either overwhelmed with large volumes of data from which they must quickly extract the most salient facts or, alternatively, relying on inadequate data from which to reconstruct the patient’s clinical course. Moreover, because patients live with their disease 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, they are best positioned to make regular observations about its progress. Such patient-constructive involvement responds to another principle of chronic care. These goals can be achieved using a simple information system that can focus the clinician’s attention on salient parameters.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree