Chapter 5

Chest pain and atrial fibrillation

Part 1: Chest pain

Introduction

Chest pain in an older person can signify a wide range of conditions from the benign and self-limiting to the life-threatening and rapidly fatal. The spectrum of causes of chest pain in older people is similar to that in younger people, but a higher index of suspicion is required because of reduced severity of symptoms in relation to the seriousness of the cause in some older people.

Many of the management principles for a patient with chest pain are the same in young and older patients; this chapter will provide guidance on how to efficiently assess an older person presenting with chest pain. Basic general management principles of the three most common life-threatening causes of chest pain will be suggested under the subheading ‘therapies to consider’, but this chapter will focus on particular anomalies or challenges relating to the presentation and management of these conditions in older people. For detailed advice on disease-specific management, supplementary use of general medical texts and local protocols is recommended.

Background

Chest pain is a common symptom, accounting for 5% of ED visits in the United Kingdom and 25% of emergency hospital admissions. In the United States, over 6 million patients present with chest pain to the ED each year. Despite the common nature of chest pain as a presenting complaint, it is a complex clinical phenomenon with a wide range of causes.

Chest pain in older adults is more likely to be associated with a serious underlying cause; however, older adults are more likely to present with vague or atypical symptoms and a delay in seeking medical care (1, 2). Older patients presenting with chest pain have a higher overall mortality (2, 3) and healthcare professionals responsible for assessing older adults with chest pain need to be systematic and thorough in their initial evaluation in order to safely rule out life-threatening causes (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Common causes of chest pain in older patients

| Life-threatening causes | Non-life-threatening causes |

| Acute coronary syndrome Pulmonary embolism Aortic dissection Myocarditis Pneumonia Tension pneumothorax Sickle cell crisis Oesophageal rupture Peptic ulcer disease Acute pancreatitis Acute cholecystitis Renal colic | Gastro-oesophageal reflux Pleurisy Costochondritis Herpes zoster Musculoskeletal pain Anxiety disorders Mitral valve prolapse Pericarditis |

Source: Adapted from Kelly BS. Evaluation of the elderly patient with acute chest pain. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007 May;23(2):327–349, vi. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.

History

A focused history of the nature of the chest pain is necessary to obtain potentially useful information when formulating a differential diagnosis.

Patients with cognitive impairment may have difficulty providing this information, and obtaining a collateral history is important in these circumstances. For more information on collateral history-taking, see Chapter 2.

Particular challenges in taking a history from patients with:

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

In a large review (4), a third of older patients with acute myocardial infarction did not present with chest pain but instead had ‘atypical’ presenting features. These included:

- Dyspnoea (49.3%)

- Diaphoresis (26.2%)

- Nausea and vomiting (24.3%)

- Syncope (19.1%).

Other ‘atypical’ symptoms experienced by older patients include worsening cardiac failure, fatigue and delirium.

Pulmonary embolism (PE)

This is common and underdiagnosed; chest pain is the second most common presenting symptom, occurring in 40–60% of patients as a presenting feature (5, 6). The PIOPED (prospective investigation of pulmonary embolism diagnosis) study found no significant difference in the frequency of chest pain as a presenting feature between young and old patients, although it did note that other common features such as dyspnoea and tachycardia were present in fewer older patients than younger patients (5). Some smaller studies have found that older patients are less likely to present with chest pain and more likely to present with non-specific symptoms such as syncope (7, 8).

Co-existing chest pathology such as cardiac failure or COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) can complicate the diagnosis of PE placing it further down on the list of differentials. Dyspnoea and chest pain can be erroneously attributed to ‘old age’ and significantly delay patients seeking medical help. A high index of suspicion is required when assessing an older patient with any chest symptoms, as morbidity and mortality associated with PE increases with age (1, 9).

Pre-test probability of D-dimer is less helpful in older patients, as many patients will have a raised D-dimer. This means that the clinician should have a lower threshold for requesting CTPA (computed tomography of pulmonary angiogram) to exclude PE in older patients.

Aortic dissection

This is an uncommon but often fatal condition, and peak incidence is in adults aged between 60 and 80 years. Timely diagnosis and early treatment have a significant impact on survival. Abrupt onset, severe central chest pain remains the commonest presenting symptom in older patients, although it occurs in only 76% of cases compared to 85–95% of younger patients (10).

Other symptoms that occur more commonly in older patients are:

- Syncope: this is the primary presenting symptom in 12–13% of cases and the only presenting symptom in 3% (1).

- Symptoms suggestive of branch vessel involvement: differing blood pressure in upper limbs, acute neurological symptoms or ischaemic limbs presenting in combination with chest pain should be considered as diagnostic of aortic dissection until proven otherwise.

A useful mnemonic (SOCRATES) to assist in taking a focused chest pain history can be found in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2 ‘Typical’ associated features of the three most common life-threatening causes of chest pain

| History | Acute coronary syndrome (likelihood ratio of acute MI) | Pulmonary embolism | Aortic dissection |

| Site | Central and left arm pain (2.7) | Lateralising | Anterior chest wall or intrascapular |

| Onset | Gradual and worsening. Time of worst pain and time of onset is important for checking cardiac biomarkers | Sudden onset | Sudden onset and maximal severity at onset |

| Character | ‘crushing’ ‘dull’ ‘heavy’ | ‘sharp’ pleuritic | Abrupt onset, sharp or ‘tearing’ ‘stabbing’ |

| Radiation | Into right shoulder (2.9) Left arm (2.8) Both arms (7.1) | – | Into back and then abdomen |

| Associated symptoms | Sweating (2.0) Nausea and vomiting (1.9) | Shortness of breath/ haemoptysis/syncope | Neurological symptoms/syncope |

| Timing | Worsens over 5–15 min | Abrupt onset maximally severe | Abrupt onset maximally severe |

| Exacerbating and relieving factors | Worsened by exertion, cold weather, emotional stress, relieved by rest or GTN | Worsened by deep breathing or position | – |

| Severity | Severity is a subjective feature useful for comparison after treatment | Severity is a subjective feature useful for comparison after treatment | Severity is a subjective feature useful for comparison after treatment |

Likelihood ratios from Panju AA, Hemmelgarn BR, Guyatte GH, et al. Is this patient having a myocardial infarction? JAMA 1998;280(14):1256.

Examination

Physical examination: general

Older patients presenting with chest pain are potentially very unwell and require an ABCDE (airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure) approach to initial assessment; physiological abnormalities should also be identified and treated at the same time.

General observation is also very important in patients with chest pain. Do they look well or unwell? Do they appear distressed or frightened? In particular, observe for signs of pallor, sweating or elevated respiratory rate.

Specific areas of focus on examination

Acute coronary syndrome

Examine the chest closely for heart murmurs or signs of associated cardiac failure. Check the pulse and promptly obtain an ECG to identify any underlying contributory or resultant arrhythmias.

Consider any underlying factors that may be contributing to the ACS such as sepsis, hypovolaemia, hypoxia or arrhythmia.

Aortic dissection

Hypertension is common in patients with aortic dissection but up to 20% of older patients can present with hypotension.

When considering aortic dissection as a diagnosis, measurement of blood pressure in both arms to identify discrepant pulse pressure of >20 mmHg is an insensitive sign of aortic dissection.

Peripheral pulse examination and neurological examination can be helpful in identifying branch vessel involvement. The presence of new, peripheral neurological signs is insensitive but highly specific in patients with chest pain.

Pulmonary embolus

Examine the legs for signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and consider any other underlying prothrombotic factors such as malignancy, recent surgery or prolonged immobility.

Look for signs of right ventricular failure, haemoptysis and cyanosis.

Investigations

Initial investigations

All patients presenting with chest pain should have:

Blood tests

FBC (full blood count), U&Es (urea and electrolytes), LFTs (liver function tests), appropriately timed cardiac biomarkers, amylase, lactate and consideration of D-dimer.

ECG

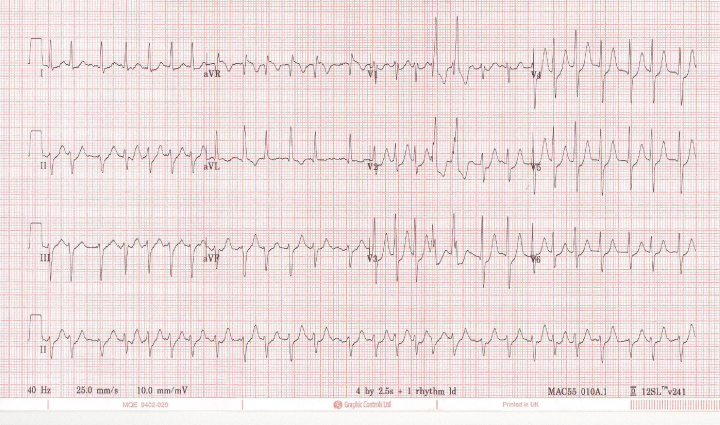

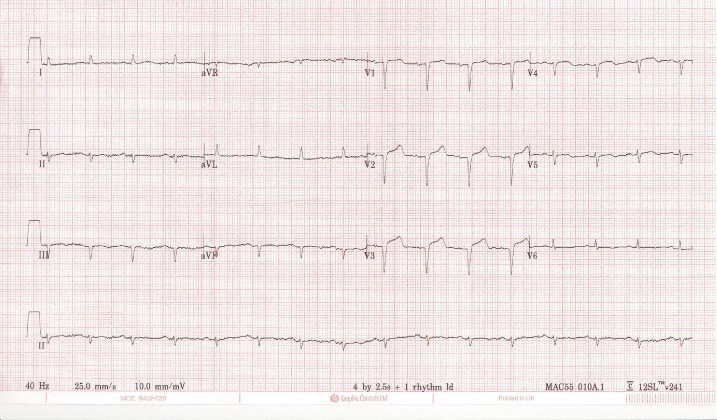

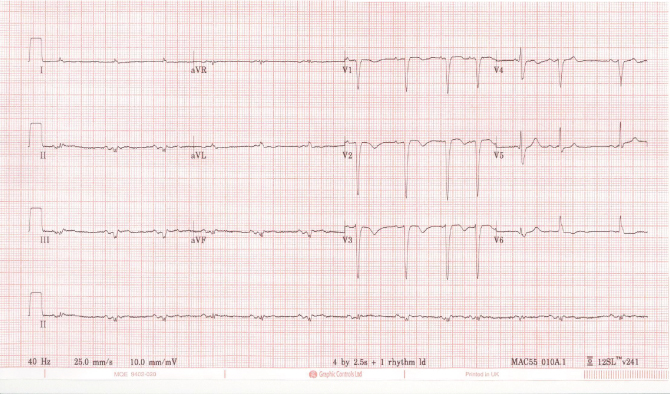

Serial ECGs every 5–15 minutes may reveal evolving ischaemic changes in a symptomatic patient. Right side ECG or extended, 15 lead, ECG can be helpful in identifying a posterior or right ventricular infarct. See Figures 5.1 and 5.3.

Figure 5.1 Uncontrolled atrial fibrillation with lateral ischaemia.

Figure 5.2 Late presentation of ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Figure 5.3 Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).

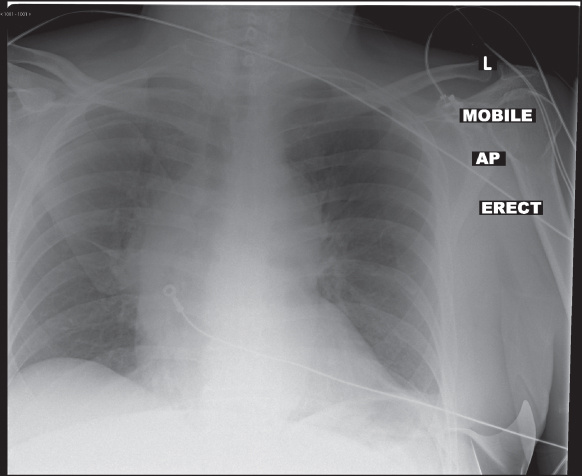

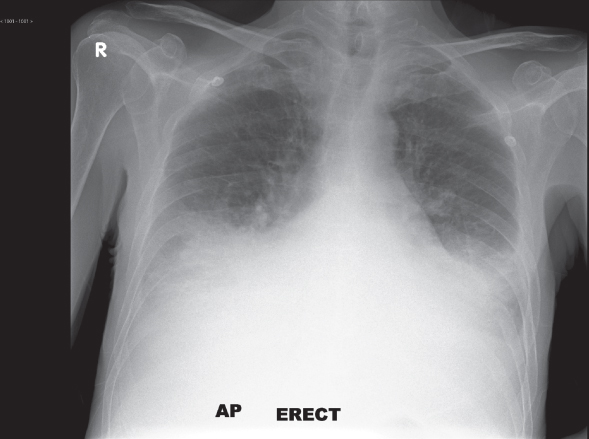

Chest radiograph

Chest radiograph is an essential investigation in all patients with chest pain. It may be normal; however, it may show relevant abnormalities, for example, pulmonary oedema in patients with cardiac failure, or a widened mediastinum in patients with aortic dissection (Figures 5.4 and 5.5).

Figure 5.4 Widened mediastinum in aortic dissection. Look also for an indistinct aortic knuckle, apical cap, and pleural effusions.

Figure 5.5 Pulmonary oedema.

Bedside ultrasound

In an ED or AMU with access to ultrasound, a quick bedside echocardiogram or thoracic ultrasound performed by an emergency physician or cardiology consultant can assess for wall motion abnormalities, pericardial effusion, pleural effusion or pneumothorax.

Further investigation

In suspected acute coronary syndrome

Patients with possible ACS should be connected to continuous cardiac monitoring in an environment with resuscitation equipment nearby. Serial troponin measurement can be helpful in identifying an evolving ACS. Consider serial ECGs to detect dynamic ST segment changes and repeat the ECG if the patient experiences further episodes of pain.

A historical ECG should be obtained for comparison if possible as many older patients have longstanding ECG abnormalities such as bundle branch blocks which can make assessing for new ischaemic changes challenging.

In suspected pulmonary embolism

Arterial blood gas (ABG)

This will typically show type 1 respiratory failure or an increased A-a gradient, and may show a respiratory alkalosis if patients are tachypnoeic. A normal ABG does not exclude a PE.

D-Dimer

PE is usually diagnosed by calculating a pre-test probability using a validated scoring system such as the Well’s score (Table 5.3), checking D-dimer and progressing to clinical imaging if necessary. In many older patients, the D-dimer will be raised at baseline and this makes excluding pulmonary embolus using this method more difficult.

Table 5.3 The two-level wells score used to calculate the pre-test probability of a hospital inpatient with suspected pulmonary embolism. Note: This test has not been validated for use in older patients

| Clinical feature | Points | Patient score |

| Clinical signs and symptoms of DVT (minimum of leg swelling and pain with palpation of the deep veins) | 3 | |

| An alternative diagnosis is less likely than PE | 3 | |

| Heart rate >100 bpm | 1.5 | |

| Immobilisation for >3 days or surgery in the previous 4 weeks | 1.5 | |

| Previous DVT/PE | 1.5 | |

| Haemoptysis | 1 | |

| Malignancy (on treatment, treated in the last 6 months, or palliative) | 1 | |

| Clinical probability simplified scores | ||

| PE likely | >4 points | |

| PE unlikely | 4 points or less | |

Clinical imaging

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree