Characteristics of Cancer Pain

It is useful to develop a scheme for the classification of cancer-related pain. One example of such a scheme is presented in Table 6.1.

CHRONICITY

Acute pain is known to occur during and after certain diagnostic procedures and various anticancer therapies, particularly postoperative pain following surgical intervention,1 pain during chemotherapy,2 or radiation therapy3 (Table 6.2). The course of acute pain is usually predictable and self-limiting, and the diagnosis of acute pain rarely is difficult. On the other hand, the assessment of patients with chronic pain tends to be much more difficult and complex. Onset of pain in these patients is often insidious, the precipitating factor less clear, and the course is prolonged and variable.

INTENSITY AND SEVERITY

It is common for health care workers to underestimate the severity of a patient’s pain,4,5 particularly when relying exclusively on their own observations. This is problematic, because pain is often undertreated when patients and physicians differ in their judgment of the pain’s severity.6 Although both severity and the degree of interference with function are crucial to the adequate assessment of pain, severity is the primary factor determining the impact of pain on the patient, and it drives the urgency and energy of the treatment process.7 Thus, the consistent measurement of pain intensity helps assess patients’ progress, provides outcome measures for research purposes, and should guide therapy.8

Patient self-report should always be the primary source of information for the measurement of pain-related issues. Observer ratings of symptom severity correlate poorly with patient ratings and are usually inadequate substitutes for patient reporting. Grossman et al.4 found a low correlation between patients’ visual analog scores for pain and those of health care providers. The discrepancies were most pronounced in those patients reporting severe pain. Although one can monitor some objective signs to clarify the manifestations and impact of certain symptoms, these signs only complement subjective assessment.

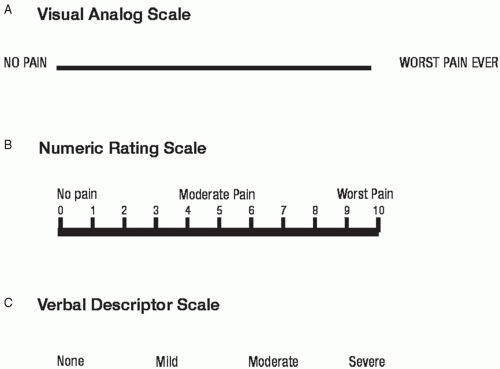

An assessment of pain intensity should include an evaluation of not only the present pain intensity but also pain at its least and worst. For research purposes, a variety of instruments are used to assess pain intensity. These instruments measure pain intensity alone, or in combination with different pain dimensions combined into a single composite score. Examples of these different dimensions include pain interference, pain affect, pain quality, and multidimension composite measures.9 Pain interference refers to the extent to which pain interferes with important activities such as mood, sleep, and interaction with others. The most common measure of pain interference in cancer pain research is the interference scale of the Brief Pain Inventory. Examples of single rating scales include the visual analog scale, numeric rating scale, verbal rating scale, graphic rating scale, faces scale, and mechanical visual analog scale (Fig. 6-1). Typically, the scale involves placing a slash mark corresponding to intensity of pain on a 100 mm line ranging from “No pain,” at one end, to the other end, “Pain as bad as it could possibly be.” The VASI has consistently demonstrated sensitivity to changes in cancer pain associated with treatment or time and usually shows strong associations with other pain intensity ratings.9 The VAS-I has also shown validity in its association with performance status, clinical setting (inpatient versus outpatient), measures of psychological distress, and measures of global quality of life.9 Despite its validity in clinical trials, there is some evidence that patients with advanced disease have more difficulty in understanding and completing the VAS-I.10 The Numerical Rating Scale of pain intensity (NRS-I) consists of a range of numbers (usually 0 to 10) and patients are asked to rate their pain intensity if 0 represents no pain and 10 the worst imaginable. NRS-I scales are used less often in research than VAS-I scales. For pain assessment in clinical settings, the VAS-I, VDS, and NRS-I approach equivalency,11 so that clarity, ease of administration, and simplicity of scoring become justifiable criteria in response scale selection. In some clinical trials, NRS-I has proven more reliable than the VAS-I, especially with less educated patients.12 Numerical scales work well as cancer clinical trial instruments, because they are easier to understand and easier to score.13 NRS-I is also sensitive to changes in pain associated with radiation therapy14 and physical therapy.15 In our practice, we commonly use numerical rating scales for the assessment of pain intensity. Verbal rating scales of pain

intensity (VRS-I) consist of a list of descriptors (eg, none, some, moderate, severe) that represent varying degrees of pain intensity. Like VAS-I and NRS-I, VRS-I demonstrates sensitivity to changes in pain with treatment, tumor size and stage, analgesic use, disease stage, and anxiety about pain.9

intensity (VRS-I) consist of a list of descriptors (eg, none, some, moderate, severe) that represent varying degrees of pain intensity. Like VAS-I and NRS-I, VRS-I demonstrates sensitivity to changes in pain with treatment, tumor size and stage, analgesic use, disease stage, and anxiety about pain.9

TABLE 6.1 CRITERIA FOR PAIN CLASSIFICATION IN THE PATIENT WITH CANCER | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 6.2 ACUTE PAIN ASSOCIATED WITH CANCER MANAGEMENT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

There are excellent correlations between all three instruments. Research has shown that differences between categorical pain severity items are not linear.16, 17 For instance, when pain severity is rated at the midpoint or higher on numeric rating scales, patients report disproportionately more interference with daily function.18 Many people, both with and without cancer, function quite effectively with a background level of mild pain that does not seriously impair or distract them. As pain severity increases to moderate intensity, a threshold is passed beyond which it is hard for the patient to ignore the pain. The pain now disrupts many aspects of the patient’s life. When pain is severe, it becomes a primary focus of attention and prohibits most activities. Pain severity and the degree to which the patient’s function is impaired are highly associated. As a way of delineating different levels of cancer pain severity, Serlin et al.19 explored the relationship between numerical ratings of pain severity and ratings of pain’s interference with such functions as activity, mood, and sleep. Based on the degree of interference with function, ratings of 1-4 correspond to mild pain, 5-6 to moderate pain, and 7-10 to severe pain. In a follow-up study in categorizing the severity of cancer pain, Paul et al.20 confirmed a nonlinear relationship between cancer pain severity and interference with function and that the boundary between a mild and a moderate level of cancer pain was at 4. However, they failed to confirm the boundary between moderate and severe cancer pain, and reported that a rating of 7 was in the moderate category and ratings >7 in the severe category.

In assessment of pain intensity, our practice is simply to use a numeric rating scale. In the interpretation of severity, we correlate the patient’s average and worst ratings with a functional assessment.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/MECHANISMS

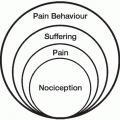

The distinction between nociceptive (both somatic and visceral) and neuropathic pain is fundamental in assessment because it influences therapy. In principle, pain results from stimulation of nociceptors or by lesions of

afferent peripheral or central nerve fibers. Pain is nociceptive if the sustaining mechanisms are related to ongoing tissue pathology. Pain is neuropathic when there is evidence that the pain stems from injury to neural tissues and aberrant somatosensory processing in the periphery or in the central nervous system. Physical influences such as pressure, traction, compression, and tumor infiltration, as well as metabolic or chemical disturbances, can produce pain. Obviously, classification by physiologic mechanism would be ideal, but sufficient information to do this is not currently available.

afferent peripheral or central nerve fibers. Pain is nociceptive if the sustaining mechanisms are related to ongoing tissue pathology. Pain is neuropathic when there is evidence that the pain stems from injury to neural tissues and aberrant somatosensory processing in the periphery or in the central nervous system. Physical influences such as pressure, traction, compression, and tumor infiltration, as well as metabolic or chemical disturbances, can produce pain. Obviously, classification by physiologic mechanism would be ideal, but sufficient information to do this is not currently available.

Tumor Involvement of Encapsulated Organs

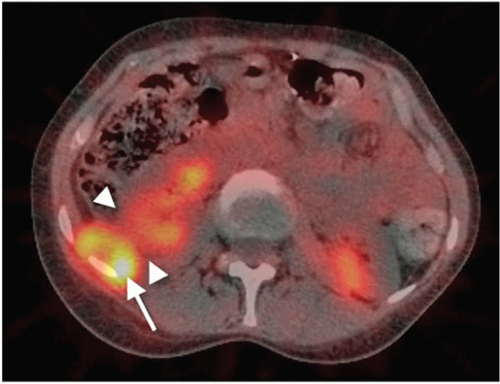

Tumors of the liver, both primary and secondary, are the most frequent examples of tumors of encapsulated organs. These can enlarge the organ to several times the normal size. Since the organ capsule of connective tissue grows less rapidly than the tumor, the intracapsular pressure rises as capsular distention develops. In addition, tumor infiltrates the capsule locally, producing dull, and, on rare occasion, stabbing pains. The massive growth of the organ not only stimulates intracapsular nociceptors, but it also irritates larger nerves by pressure or traction on the tissue suspending the organ. Similar organ-enlarging processes in the spleen and kidneys do not lead to pain to the same extent as in the liver, perhaps because of the more stable suspension or embedding of these organs, which are farther away from the midline with its abundant nerve pathways. Kidney tumors produce pain only when the kidney has been almost completely destroyed and the tumor has invaded the pararenal tissue, or when it destroys the renal pelvis. Extrarenal tumor compression on the kidney or ureter can result in severe flank pain (Fig. 6-2).

The brain is also an encapsulated organ. Its unique feature is that the bony skull prevents any generalized enlargement after puberty. Pain arises not by destruction of parenchyma but by the increase of intracranial pressure with stimulation of the meningeal and blood vessel nociceptors. Such an increase of intracranial pressure occurs with space-occupying tumor growth or in focal or generalized brain edema. Focally, edema can develop around neoplasms or damaged brain from trauma or vascular compromise. Generalized edema develops in diffuse metastatic invasion of the meninges due to disturbance of the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Such a tumor invasion of the leptomeninges is frequent in malignant lymphomas. However, metastatic invasion of the leptomeninges can also occur in patients with solid tumors, eg, bronchial and breast carcinoma, and malignant melanoma, with the predominant symptom being headache (Fig. 6-3). In such cases, tumor infiltration of cranial nerves may also occur and lead to focal pain.

Tumor Infiltration of Peripheral Nerves

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree