As the population ages, oncologists will be faced with managing an exploding number of older patients with breast cancer. The primary challenge of caring for older cancer patients is providing treatment options that maximize long-term survival while accounting for comorbidities, life expectancy, and effects of treatment. There is a paucity of data from trials on the risks and benefits of effective treatments in elderly breast cancer patients. This article discusses how to evaluate older breast cancer patients and provides guidelines for optimal therapies in the adjuvant and metastatic treatment settings.

Key points

- •

The US population is aging, and increasing age is the major risk factor for breast cancer.

- •

Treatment decisions are not based on age but estimated survival.

- •

Adjuvant therapy decisions are based on breast cancer stage and phenotype, patient goals, treatment options, potential toxicity, and estimated survival.

- •

All therapy is palliative in the metastatic setting, and controlling symptoms and maintaining quality of life are the key goals of treatment.

- •

Partnering with geriatricians, internists, and family practitioners optimizes patient management.

Introduction

In the United States and other developed nations, the incidence and mortality rates for breast cancer rise dramatically with increasing age, making aging the major risk factor for breast cancer. For example, at present, the risk of developing a new breast cancer is 1 in 15 for women 70 years old as contrasted to 1 in 203 for those younger than 39 years old. Moreover the current aging of the US population will compound these numbers and lead to major increases in the number of older women with breast cancer. The median age of onset of breast cancer is approximately 61 years in the United States and a majority of women who die of breast cancer are 65 years and older. Of the 130,000 estimated new breast cancers in the United States, in 2013, 40% will be in women older than 65 years. In addition, of the approximately 3 million breast cancer survivors in 2012, a majority are greater than 65 years. The challenge of caring for older women is tailoring the treatment to fit the patient. Although this is true for all patients, it is germane in elders, in whom comorbidity and functional loss can lead to undertreatment and the risk for shorter breast cancer–specific survival or to overtreatment and needless toxicity.

Most practicing oncologists have not had geriatric training but still may think they have the necessary knowledge and skills to make optimal treatment decisions; available data suggest this is not the case. A common error is to equate chronologic age with physiologic age in making treatment decisions. There can be wide variability in estimated survival for patients of the same age, however, depending on their comorbidities and general health status. As an example, a 75-year-old woman in average health has an estimated survival of 12 more years whereas an 85-year-old woman has approximately 7 years ( http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0105.pdf ). This article focuses on issues directly related to treatment decisions for older women with breast cancer, including defining the goals of treatment, estimating survival, and selecting appropriate therapy in the adjuvant and metastatic settings. Other outstanding reviews on this topic have also been published. Table 1 provides a list of Web sites that are helpful resources when making treatment decisions for older patients with breast cancer and other cancers.

| Site | Web Address |

|---|---|

ePrognosis

| www.eprognosis.org |

POGOe

| www.pogoe.org |

Adjuvant! Online

| www.adjuvantonline.com |

PREDICT

| www.predict.nhs.uk |

Cancer and Aging Research Group

| www.mycarg.org |

Moffitt Cancer Center CRASH Score

| www.moffitt.org/saoptools |

UNC Lineberger Geriatric Oncology

| http://unclineberger.org/geriatric |

| World Health Organization FRAX | www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX |

Introduction

In the United States and other developed nations, the incidence and mortality rates for breast cancer rise dramatically with increasing age, making aging the major risk factor for breast cancer. For example, at present, the risk of developing a new breast cancer is 1 in 15 for women 70 years old as contrasted to 1 in 203 for those younger than 39 years old. Moreover the current aging of the US population will compound these numbers and lead to major increases in the number of older women with breast cancer. The median age of onset of breast cancer is approximately 61 years in the United States and a majority of women who die of breast cancer are 65 years and older. Of the 130,000 estimated new breast cancers in the United States, in 2013, 40% will be in women older than 65 years. In addition, of the approximately 3 million breast cancer survivors in 2012, a majority are greater than 65 years. The challenge of caring for older women is tailoring the treatment to fit the patient. Although this is true for all patients, it is germane in elders, in whom comorbidity and functional loss can lead to undertreatment and the risk for shorter breast cancer–specific survival or to overtreatment and needless toxicity.

Most practicing oncologists have not had geriatric training but still may think they have the necessary knowledge and skills to make optimal treatment decisions; available data suggest this is not the case. A common error is to equate chronologic age with physiologic age in making treatment decisions. There can be wide variability in estimated survival for patients of the same age, however, depending on their comorbidities and general health status. As an example, a 75-year-old woman in average health has an estimated survival of 12 more years whereas an 85-year-old woman has approximately 7 years ( http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0105.pdf ). This article focuses on issues directly related to treatment decisions for older women with breast cancer, including defining the goals of treatment, estimating survival, and selecting appropriate therapy in the adjuvant and metastatic settings. Other outstanding reviews on this topic have also been published. Table 1 provides a list of Web sites that are helpful resources when making treatment decisions for older patients with breast cancer and other cancers.

| Site | Web Address |

|---|---|

ePrognosis

| www.eprognosis.org |

POGOe

| www.pogoe.org |

Adjuvant! Online

| www.adjuvantonline.com |

PREDICT

| www.predict.nhs.uk |

Cancer and Aging Research Group

| www.mycarg.org |

Moffitt Cancer Center CRASH Score

| www.moffitt.org/saoptools |

UNC Lineberger Geriatric Oncology

| http://unclineberger.org/geriatric |

| World Health Organization FRAX | www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX |

Defining the goals of treatment

It is key before discussing treatment options with a patient that an oncologist makes clear to the patient the goals of therapy. Is treatment recommended to improve survival, as in the adjuvant setting, or to improve quality of life and control cancer-related symptoms, as in the venue of metastatic disease? The purposes of treatment in the adjuvant and metastatic settings are easily defined, but the functional (and today the financial) price paid to achieve them may differ greatly in older versus younger women. Treatment goals in elders are likely to differ substantially from younger women. For younger patients maintaining relationships, raising children, and being gainfully employed are major issues and result in younger patients more willing to accept serious toxicities for longer survivals. Older patients frequently have different goals. In a seminal study in which older patients were offered a treatment that would improve survival, 75% would refuse treatment if it were associated with a risk of severe functional impairment whereas almost 90% would refuse for a risk of severe cognitive loss. For older women living independently, not being a burden on their families is a major concern and oncologists must factor this in to their treatment recommendations. Being clear on the goals of treatment is essential in the care of all patients, but especially in elders, where a physician’s preferences may not be similar to the patient’s.

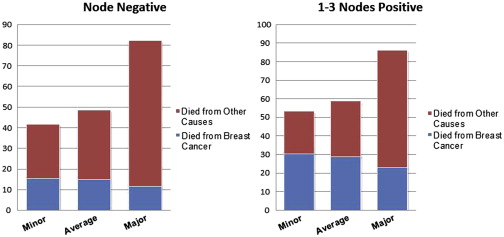

Estimating survival and geriatric assessment

Once the goals of treatment are defined, a patient’s estimated survival from non–breast cancer causes should be assessed. Such estimates can be obtained from Web-based calculators available on www.eprognosis.org and derived from key studies of elders. These calculators, although not perfect, are generally better than an educated guess and rely on clinical as well as functional information that can be obtained as part of the history and physical examination and a brief geriatric assessment. An example of how these calculators can help estimate survival is shown in Table 2 . For women with breast cancer, survival can also be estimated using the calculator in Adjuvant! Online ( www.adjuvantonline.com ). This program uses US census data to estimate life expectancy based on age at breast cancer diagnosis and allows clinicians to provide an estimate of general health that may also influence survival and potential benefits of treatment. Such information can be of great help because for most breast cancer patients, especially elders, the likelihood of dying of a non–breast cancer cause is greater than that of breast cancer ( Fig. 1 ). The likelihood of non–breast cancer–related mortality helps put the benefits of breast cancer adjuvant therapy into better perspective.

| Variable | Patient 1 | Patient 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 75 | 75 |

| Gender | Female | Female |

| Smoking | Never | Former |

| BMI | 30 | 23 |

| History of Ca | No | No |

| Diabetes | No | Yes |

| COPD | No | Yes |

| Hospitalizations past year | None | Once |

| Self-rated health | Excellent | Fair |

| Dependent IADL | None | 1 |

| Difficulty walking 1/4 mile | No | Yes |

| 5-y Mortality | 6% | 43% |

| 9-y Mortality | 16% | 75% |

The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) and Karnofsky Performance Status are commonly used by oncologists as a global assessment of function in cancer patients. Although these measures correlate well with cancer-related mortality, they are an inadequate measure of functional impairment in elders. A comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) assesses functional status, comorbidity, medication use, cognition, social support, and nutritional status, all key domains related to quality of life and longevity. The CGA can help identify problems that can be improved or overcome by interventions that have been shown beneficial in improving quality of life and reducing morbidity in older patients. Unfortunately, CGA is a time-consuming process, which, coupled with the lack of available geriatricians, makes it impractical for older cancer patients. To compensate, several validated screening tools can be used to identify vulnerable and frail patients who can then be referred for a more comprehensive assessment.

An abbreviated geriatric assessment that evaluates key domains has also been shown feasible in the clinical trials setting. This assessment takes approximately 10 minutes of professional time to perform a brief mental status evaluation and up-and-go test and approximately 20 minutes of a patient’s time to provide self-reported information on other key domains, such as activities of daily living (which evaluates tasks, such as washing and dressing, that are necessary for caring for oneself), instrumental activities of daily living (tasks, such as cooking and paying bills, that allow living independently), depression and anxiety (common problems in older patients that are frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated), comorbidity, medications, nutritional status, and social support. Information from the CGA can be used to inform models that predict survival (such as the www.eprognosis.com calculator [discussed previously]) and chemotherapy-related toxicity (discussed later) as well as to identify other problems, such as poor function, lack of social support, polypharmacy, and poor nutrition—all which lend themselves to potentially beneficial interventions. The International Society of Geriatric Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend that CGA be performed on older patients with cancer.

Predicting chemotherapy toxicity

Toxicity is a concern of all breast cancer patients offered treatment, but especially elders, in whom side effects, such as neuropathy and fatigue, can convert an independent community living elder to someone needing institutional care. Two tools are now available that use both clinical information generally collected as part of the standard patient evaluation and items collected in a geriatric assessment. The Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score, available online at www.moffitt.org/saoptools , provides 2 subscores that predict the risk of grade 4 hematologic toxicity and grades 3 to 4 nonhematologic toxicity. This tool assigns a toxicity risk to different chemotherapy regimens and includes diastolic blood pressure, activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, ECOG performance status, mental status, and nutritional status to predict toxicity.

A second calculator has been developed by the Cancer and Aging Research Group ( www.mycarg.org ). Like the CRASH score, this tool uses clinical and geriatric assessment data and provides a score predictive of grades 3 to 5 toxicity. The score was derived from a study of 500 patients 65 years and older who had a brief geriatric assessment prior to chemotherapy and included patients with different stages I to IV cancers; grades 3 to 5 toxicity were noted in 53% of the entire group and 2% died of treatment-related toxicity. Karnofsky Performance Status in this study was not predictive of toxicity, although the model clearly distinguished between low-risk and high-risk groups.

Ductal carcinoma in situ

With the advent of routine screening mammography, an increasing proportion of breast cancer patients are diagnosed with preinvasive in situ cancers. Although some patients with extensive ductal cancer in situ (DCIS) may undergo mastectomy, another proved approach to management includes lumpectomy (with re-excision if necessary to achieve negative margins) and adjuvant breast radiation. There may also be favorable subsets of patients with DCIS for whom it is reasonable to consider deferring adjuvant radiation.

In a meta-analysis incorporating individualized patient data from 4 randomized trials in patients with DCIS, the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group found that adjuvant radiotherapy reduced the absolute 10-year risk of ipsilateral breast events by approximately half (28.1% with breast conservation surgery alone to 12.9% with breast conservation surgery plus RT), with an absolute reduction in breast recurrence of 15.2% at 10 years. The proportional reduction in breast cancer recurrence was greater for the more advanced age cohorts. Although approximately half of recurrences were invasive cancers, the addition of radiation did not increase breast cancer–specific or overall survival.

Prospective observational studies have been performed in low-risk patients with DCIS treated with lumpectomy alone. In one trial the 5-year ipsilateral recurrence rate was 12% in patients who did not receive tamoxifen and had tumors smaller than 2.5 cm that were low or intermediate grade, and with at least a 1-cm surgical margin. In this series, approximately half of the patients enrolled were premenopausal. Another trial found an overall 6.1% 5-year ipsilateral recurrence rate in patients with tumors smaller than 2.5 cm, low or intermediate grade, and 3-mm surgical margins. The median age in that series was 60, and the median tumor size was 5 mm. There was a 15.3% recurrence rate in the subset of patients with high-grade tumors and 10% of patients in this trial received tamoxifen. The investigators concluded that, for patients with low-grade or intermediate-grade tumors meeting these clinical criteria, that radiation could be omitted. A randomized trial of breast conserving surgery with or without radiation in this good-risk DCIS population (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 9804) has been reported in abstract only. This trial closed early due to poor accrual (n = 636), but a statistically different difference in ipsilateral recurrence at 5 years was seen (3.2% no radiation vs 0.4% with radiation). These data suggest that it is reasonable to omit breast radiation in elderly DCIS patients with low-grade to intermediate-grade lesions smaller than 2.5 cm with negative margins (at least 3 mm) given the low rate of in breast recurrence and lack of impact on breast cancer–specific or overall survival.

Early-stage breast cancer

Selecting Systemic Adjuvant Therapy

In women 70 years and older, a majority of breast cancers are hormone receptor positive (HR+) and HER2-negative (HER2−). These breast cancers have significantly different clinical courses and outcomes compared with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) (estrogen receptor [ER] negative, progesterone receptor negative, and HER2−) and with HR−, HER2+ cancers. For HR+, HER2− tumors, a majority of relapses for patients given adjuvant endocrine therapy are seen years after initial diagnosis, with a continued hazard for relapse of 1% to 2% per year after 5 years, and a vast majority of cancer deaths in this group are seen well after 5 years. Conversely, a majority of patients with TNBC or HR−, HER2+ breast cancers relapse much earlier (generally within 5 years), with cancer deaths occurring earlier as well. This difference in clinical course, based solely on HR phenotype, has profound treatment implications, particularly for older patients with short estimated survival times.

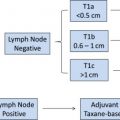

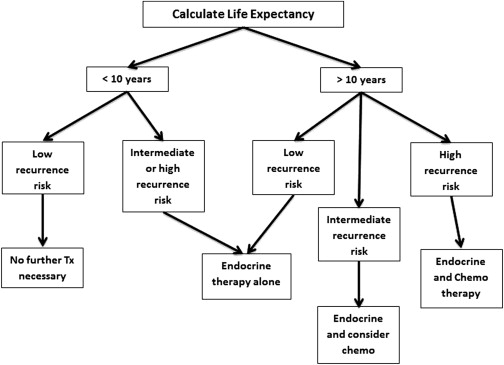

Endocrine therapy is the linchpin of adjuvant treatment of older women with HR+, HER2− breast cancer. The major challenge in older patients with HR+, HER2− breast cancer is determining who would potentially benefit from chemotherapy. The addition of chemotherapy to endocrine therapy improves survival in some women with HR+ early-stage breast cancer but for the majority, chemotherapy provides modest or no survival benefit. Unfortunately the data on chemotherapy are sparse for patients 70 years and older and the likely benefits of chemotherapy can vary greatly depending on the biologic characteristics the tumor. Older patients with HR+, node-negative, 1 to 3 node-positive tumors, and a life expectancy less than 10 years are excellent candidates for endocrine therapy. Few of these patients will benefit from chemotherapy and treatment can cause substantial toxicity, including potential loss of function and diminished quality of life that are unacceptable. (See Fig. 2 for a general algorithm to the approach of an older patient with HR+, HER2− breast cancer based on life expectancy.) Only after estimating non–breast cancer–related life expectancy can the potential benefits of chemotherapy be determined. For patients with T1 and T2 node-negative, HR+ tumors who receive adjuvant endocrine therapy, the added value of chemotherapy can be estimated by the Oncotype DX assay (Genomic Health, Redwood City, California). Recent data from this assay suggest that the primary benefit of chemotherapy in this patient group is in those with high recurrence scores, with minimal value among patients with low recurrence scores, including women with 1 to 3 positive nodes. The authors suggest that patients with intermediate recurrence scores also be evaluated using Adjuvant! Online to estimate the added value of chemotherapy in reducing breast cancer mortality. The value of chemotherapy in patients with T1 and T2 node-negative lesions with a low-intermediate recurrence score is also being evaluated in a randomized clinical trial (Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment [Rx]); clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00310180 ). The trial is closed to accrual, and the results are expected in 2015. A similar trial is ongoing in women with 1 to 3 positive lymph nodes.

TNBC and HER2+ breast cancers are each seen in approximately 15% of older patients. For TNBC, chemotherapy is the only systemic therapy of benefit and should be considered for most fit older patients. HER2+ cancers that are HR−, the most ominous phenotype when untreated, have a better outcome than TNBC since the advent of chemotherapy and trastuzumab (Herceptin). For those patients with small HR+, HER2+ (triple-positive) lesions, who have a better short-term prognosis than those with HR−, HER2+ tumors, the decision regarding the use of chemotherapy and trastuzumab must be individualized, especially in less fit patients.

Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy

Randomized trials in patients older than 70 years with HR+ tumors have shown that adjuvant tamoxifen reduces the annual risk of recurrence of breast cancer by approximately half and the annual odds of dying from breast cancer by 37%, irrespective of nodal status. The absolute benefit can vary greatly, however, and is small for patients with cancers that have a low risk of recurrence. Tamoxifen is generally well tolerated in older patients and is available at a low cost. Tamoxifen can also maintain or improve bone density and lower cholesterol levels in postmenopausal women. There is, however, an approximately 1% risk of endometrial cancer and venous thrombosis associated with 5 years of use. In older patients, the requirement for a pelvic examination and Papanicolaou smear yearly can be an obstacle.

Many large clinical trials have been performed that compared tamoxifen to aromatase inhibitors (AIs) and a small improvement in relapse-free survival of a few percentage points has been shown with the use of AIs; however, there is no convincing improvement in overall survival. Updated American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines for use of endocrine therapy are available. Although there are many strategies regarding endocrine therapy, the initiation of tamoxifen and then changing to an AI 2 to 3 years later has been shown to improve survival by approximately a percentage point and may represent the best strategy. Until recently, AIs were expensive, but their cost has significantly dropped since going off patent. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines have recommended that AIs be considered for use in all postmenopausal patients at some time during their endocrine treatment. AIs, although not associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer or thromboembolism, can cause severe arthralgia and myalgia that can impede function, although the toxicity of AIs seems less in elders. Changing to another AI can be helpful in some patients experiencing these symptoms, but, if symptoms persist, switching to tamoxifen is probably the best strategy.

AI therapy is associated with accelerated bone loss and an increased risk of fracture. Many older patients already have baseline osteopenia or osteoporosis at diagnosis, and these patients are particularly at risk from further bone loss. Older adults on AI therapy should be encouraged to exercise regularly as well as take the recommended daily doses of vitamin D and calcium. For patients with osteoporosis, treatment with either bisphosphonates or other bone-protecting agents, such as denosumab, should be considered. The World Health Organization fracture risk assessment tool, FRAX, can be used to estimate fracture risk from clinical and bone densitometry data ( www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX ) that can assist in decision making.

Nonadherence to medications can occur for a variety of reasons and older adults are particularly susceptible. Many are prescribed several medications for treatment of comorbidities, making for complicated medication regimens and polypharmacy. Other factors related to adherence include cognitive, visual, and physical impairments. In a recent systematic review of adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors, adherence ranged from 41% to 72% and discontinuation ranged from 31% to 73%, with older age a risk factor for nonadherence. Although the best way to improve medication adherence is unclear, educating older patients and their families about the value of treatment and possible side effects is important. Many family members and other caregivers play a vital role in assisting patients with their medications. Patients should also be queried on each clinic visit as to the medications they are taking and specifically asked about their adherence to their prescribed endocrine treatment.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy

The decision to recommend chemotherapy to an older patient is complicated. The decision requires consideration of the effect of treatment on improving survival as well as balancing potential toxicity that may result in loss of function or reduced quality of life. To further complicate the decision, the social (increased need for family support) and financial costs of treatment must also be considered. Like endocrine therapy, chemotherapy results in similar proportional reductions in recurrence and survival, irrespective of nodal status. Once the decision to recommend chemotherapy is made, a second difficult decision for the medical oncologist is which chemotherapy regimen to recommend.

Adjuvant! Online is a useful tool to use when making treatment selections because it directly compares survival outcomes for different chemotherapy regimens. It categorizes regimens as to first, second, and third (the most aggressive) regimens for defining treatment benefit ( Table 3 ). Older first-generation chemotherapy regimens, such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil and doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC), have been supplanted by newer, more-effective second-generation and third-generation treatments. The second-generation regimen of 4 cycles of docetaxel cyclophosphamide (TC) is superior to 4 cycles of AC and has been tested in large numbers of older patients and is generally well tolerated. Estimates of effectiveness of second-generation and third-generation chemotherapy regimens by Adjuvant! Online for older patients have not been validated in clinical trials and it is possible that the value of such regimens is overestimated in older patients. For fit patients who are at a high risk of relapse, treatment with third-generation regimens improves survival by a few percentage points compared with first-generation or second-generation regimens. For patients who are not at high risk of relapse, the authors suggest consideration of second-generation regimens, such as TC, to avoid potential anthracycline cardiac and hematologic (myelodysplasia and acute leukemia) toxicity. For those at high-risk, a third generation regimen should be considered if estimates suggest an improvement of a few percent or more in 5-year survival. These third-generation, anthracycline-containing regimens should generally be reserved for patients who are highly functional with minimal comorbidity. A large retrospective study of node-positive patients in randomized trials compared less-intense with more-intense chemotherapy and showed that treatment with more-intensive regimens in both older and younger patients resulted in a similar proportional improvement in relapse and survival rates.