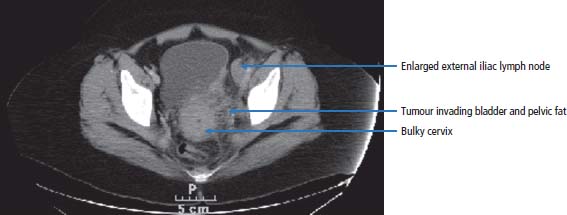

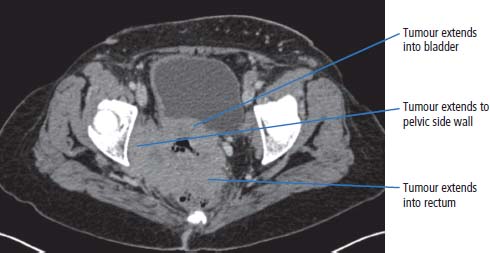

17 We are at a point where we may be able to consider the elimination of cervical cancer from our population. This is because of the development of effective vaccines against the cause of the vast majority of cervical cancers. The only major obstacles against the implementation of vaccination programmes are religious prejudice and the financial backing to support vaccination programmes in non-industrialized countries. Cervical cancer cells are one of the most important of the tools in the laboratory armamentarium. The history of the development of cervical cancer cell lines tells a story that encapsulates research developments and contemporary attitudes to research. In 1951, George Otto Gey developed HeLa, the first human cancer continuous cell line. These cells proliferate in tissue culture and have been the basis of a great deal of research into cancer biology and drug development. The sample originated from the cervical cancer of a young black woman, Henrietta Lacks of Baltimore. Many thousands of tons of HeLa cells are now found in the incubators and freezers of laboratories around the world. Unfortunately the patient died less than a year after the cell line was established, and her family are said to be shocked by the development and proliferation of the cell line, which was obtained presumably without consent at the time. Cancer of the cervix is thought to affect over one-third of a million women worldwide and represents 10% of all female cancers (see Figure 1.15). Eighty per cent of all cases of cervical cancer occur in the developing world. The incidence in the United Kingdom, as in many developed countries, is decreasing. In 2011, 3064 women were diagnosed and 972 women died of cervical cancer in the United Kingdom (Table 17.1). Invasive cervical cancer is believed to be the final stage in a continuum that starts with infection of the cervix by high-risk genotypes of human papillomavirus (HPV) and progresses via cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) to invasive cancer (see Box 1.2). CIN is a cytological diagnosis and is divided into three grades (CIN1–3). The histological equivalent of CIN is the squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL), which is divided into low-grade SIL (LGSIL) that is similar to CIN1 and high-grade SIL (HGSIL) analogous to CIN2 and CIN3. There are over 100 genotypes of HPV and some are associated with a higher risk of cancer than others (see Chapter 2). Three-quarters of cervical cancers contain either HPV 16 or HPV 18 the two most common high risk HPV genotypes and a further 10% harbour HPV 31 or HPV 45. It is thought that cervical cancer only occurs in the presence of HPV and that HPV is the first identified example of a “necessary cause” of a human cancer. The risk of acquiring HPV infection rises with the number of sexual partners, whilst the risk of CIN3 increases with age at first sexual intercourse and with smoking. Smoking is not a risk factor for HPV infection but appears to co-operate with HPV infection in the pathogenesis of CIN and cervical cancer. HPV infection is also associated with cancers of the vulva, vagina, penis, anus and oropharynx. HPV infection has been estimated to cause 4.8% of the world’s cancers. Table 17.1UK registrations for kidney cancer 2010 In 1928, a Greek cytopathologist Georgios Papanicolau invented a cervical cytology smear test to detect cancer cells that has saved thousands of lives. Despite living until 1962, Papanicolau never received a call from the Nobel committee in Stockholm, although he did appear on the 10,000 drachma banknote before Greece adopted the Euro. Cervical smear screening was introduced in the United Kingdom in 1964 and the current programme is for women aged 25–49 to have screening every 3 years and women aged 50–65 to have smears every 5 years. Around 80% of women attend for their screens and 4.5 million women are screened every year. Screening has reduced the incidence of cervical cancer by over 50%. Of the women who have an abnormal smear test, 0.1% have cancer, 7% CIN3, 11% CIN2 and 25% CIN1. Screening by smear cytology is a subjective process, which, although well regulated, may be subject to human error. The introduction of liquid cytology has improved the diagnostic accuracy and this may be further improved when testing for HPV infection is added to the screening. It has been estimated that cervical cancer screening saved over 8000 lives in the United Kingdom in the decade 1988–1997. The central role of HPV infection in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer led to vaccination strategies. Recombinant HPV viral coat proteins self-assemble into hollow virus-like particles that lack DNA so are unable to replicate but are immunogenic. A quadrivalent vaccine made up of VLP of HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18 protects against 98% of CIN and cancer caused by HPV 16 and 18. In the United Kingdom, girls aged 12–13 years have been offered this vaccine since 2008. The quadrivalent vaccine also confers immunity against HPV 6 and 11, the main causes of genital warts. Women with cervical cancer usually present to their doctors with inter-menstrual bleeding, post-coital bleeding or painful intercourse. There may be a vaginal discharge that can be bloody or offensive or symptoms suggestive of a urinary infection such as urinary frequency or urgency. When the cancer has spread, common symptoms include back pain due to enlarged abdominal lymph nodes or referred pain in the legs due to involvement of the nerve plexuses of the pelvis. These symptoms may be accompanied by loss of weight. The examination should include an assessment of the patient’s general state of health together with palpation of the abdomen and a vaginal assessment. This may confirm the presence of a discharge and reveal a cervical mass (Figure 17.1). The GP should refer the patient to a gynaecologist who will repeat the examination, take smears from the cervix for cytological examination and then organize admission for examination under anaesthesia and cervical biopsy. Colposcopy should be performed as an outpatient procedure prior to admission. This technique allows direct visualization of the cervix with properly directed biopsies. After these assessments have been performed and a histological diagnosis has been obtained, staging investigations should be organized. These should include a full blood count, profile, chest X-ray and a CT or magnetic resonance scan of the abdomen and pelvis. Figure 17.1 Cervical cancer with extensive, locally infiltrating tumour. This CT scan of a 65-year-old woman who had never had a cervical smear shows a bulky cervix with loss of the normal fat plane that separates it from the bladder. There is extension of the invasive cervical cancer into the posterolateral bladder wall anteriorly and into the pelvic fat laterally. There is also an enlarged left external iliac lymph node. The staging was therefore T4N1M0 (Stage 4A). Carcinoma of the cervix is staged as a result of these findings as follows: Figure 17.2 Stage 4B cervical cancer. Tumour invasion into the bladder and rectum denotes T4 disease but in addition there was spread to regional lymph nodes (N1) and to retroperitoneal lymph nodes (M1). Hence the FIGO stage is 4B. Sixty-six per cent of cervical cancers are squamous cell tumours. These are graded as G1, G2 or G3 tumours, according to their microscopic appearance: G1 tumours are well differentiated, G2 tumours moderately and G3 tumours poorly differentiated. Fifteen per cent are adenocarcinomas, and these are also graded G1–3. Other rarer tumours include small cell cancers and lymphomas. Carcinomas in situ are graded I–III and abbreviated to CIN or cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia (CGIN), depending on whether squamous or adenocarcinoma cells are present. The treatment of cervical cancer depends upon the stage of disease. Stage 0 carcinoma of the cervix should be treated by cone biopsy or by surgical excision. Stage 1A disease is usually treated by hysterectomy, although more limited approaches with cone biopsy, local excision or radical trachelectomy have their advocates. Stage 1B and 2A cervical cancer is usually treated by either radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy or by pelvic irradiation. Both methods are equally effective in the long-term control of the disease. Stage 2B and 3 carcinoma of the cervix should be treated by pelvic radiotherapy and stage 4 carcinoma with chemotherapy. Patients treated with pelvic radiotherapy with curative intent are frequently prescribed additional concurrent adjuvant chemotherapy. Typically, patients will be treated with weekly courses of single-agent cisplatin. Chemoradiation has been subjected to a number of randomized trials, and it has been concluded that concomitant chemoradiation appears to improve overall survival and progression-free survival in locally advanced cervical cancer. Consideration is also given to treatment with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in some centres, but its role is not defined in cervical cancer. The side effects of radiotherapy include an early menopause and radiotherapy-related bowel and bladder toxicity. Ovarian conservation is offered to younger patients treated by hysterectomy. Progressive or metastatic cervical carcinoma is treated with combination chemotherapy usually using a regimen that includes cisplatin. As a result of treatment, virtually 100% of patients with CIN disease are cured. Approximately 0.05–0.3% of treated women subsequently develop invasive carcinoma. If CIN is left untreated, then over a 30-year follow-up period, 10–40% of patients will develop invasive cancer. The evidence for this is based on data from a single study carried out in New Zealand of untreated patients with CIN, by a clinician who apparently was convinced that CIN did not progress. The standard management for CIN is colposcopy with local ablation by cone biopsy, cryotherapy, laser therapy or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). Approximately 5% of patients treated for stage 1A carcinoma of the cervix will progress to develop advanced disease. Sixty-five to eighty-five per cent of all patients with stage 1B and 2A carcinoma of the cervix survive 5 years after treatment by a radical hysterectomy or radiation. The chance for a cure is smaller in stage 2B disease, and the expectation is that approximately 50–65% survive with radiotherapy alone. About 40–60% of patients with stage 3A disease and 25–45% of patients with stage 3B disease survive 5 years and are treated with radiotherapy and frequently with chemotherapy. These statistics are relevant to patients with squamous cancers or adenocarcinomas. Variant histologies, such as small cell carcinomas, are associated with a poor prognosis, with the expectation that, even at an early stage, survival is less than 5% at 5 years. Patients with stage 4 cervical cancer do very poorly. In this situation, it is very unlikely that a cure will be achieved. Chemotherapy is the treatment of first choice. A number of agents have activity in the order of 15% and their combination is accompanied by some synergy of effect. Cisplatin is the single agent with the greatest activity, but it is commonly used in combination with paclitaxel or topotecan. About 30–40% of patients will respond to treatment, but durable responses are rare. Chemotherapy is associated with toxicity, and this includes nausea and vomiting, hair loss, infections and kidney failure. Because of the toxicities of treatment, an alternative approach is to palliate symptoms with pain killers alone. In the terminal phases of illness, patients with cervical cancer may have a number of problems that prove difficult to manage. These include fistulae from the vagina to bladder and from the rectum to vagina or bladder, as a result of local progression of the tumour. Obstruction of kidney function may occur as a result of blockage of the ureters, either by enlarged lymph nodes or by tumour from the cervix growing within the pelvis, blocking the ureters. These situations can be treated surgically, in which case a colostomy or ileostomy may be formed, relieving bowel or ureteric obstruction or radiologically by the passage of a stent to reverse obstructive damage to the kidneys. A good life quality can be obtained by limited interventions. Case Study: The dignified Rwandan.

Cervical cancer

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registrations

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5-year overall survival

Cervical cancer

2

12th

1 in 139

+10%

67%

Screening

Prevention (vaccination)

Presentation

Outpatient diagnosis

Staging and grading

Treatment

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

Prognosis

Terminal care

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree