E1

E2

E4

E5

E6

E7

L1

L2

ATPase

Regulator of E6 and E7

Disrupts cytokeratin matrix for release of virions

Potentiation of membrane bound EGF receptors

Bind and inactivate p53

Bind pRB leading to E2F activity

Major capsid (conserved)

Minor capsid (variable)

Fig. 2.1.

Human papillomavirus genome [4]. Reprinted from Clinical Gynecologic Oncology, 7th Edition, Di Saia PJ, Creasman WT. Chapter 3 Invasive Cervical Cancer, Monk BJ, Tewari KS, Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier. Clinical gynecologic oncology by Di Saia PJ, Creasman WT. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier Mosby in the format reuse in a book/textbook via Copyright Clearance Center.

HPV is detectable in over 95 % of squamous cell carcinomas and 30–40 % of adenocarcinomas.

High-risk strains cause a mutation of cells in the squamocolumnar junction leading to cervical dysplasia and cancer.

Incidence of progression without treatment:

CIN1 (16 %), CIN2 (30 %), CIN3 (70 %).

CIN3 → invasive disease: 0–20 years.

Risk factors:

Lower socioeconomic status.

Multiple sexual partners, early age of first intercourse, promiscuous partners, co-infection with other sexually transmitted diseases.

Tobacco use.

Immunocompromised conditions (HIV or pharmacologic).

The greatest risk for developing cervical cancer is infrequent or no prior screening.

In many South American, African, and Asian countries, cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer related death in women.

Prevention

Abstinence prevents HPV related cervical carcinomas, but the large majority of women are sexually active and therefore at risk for exposure to HPV infection.

Two US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved vaccines indicated to prevent cervical cancer (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2.

HPV directed vaccines.

Gardasil

Cervarix

HPV types

6,11, 16, 18

16, 18

Dose schedule

0.5 mL IM 0, 2, 6 months

0.5 mL IM 0, 1–2, 6 months

Indications

Cervical cancer, CIN, AIS, Vulvar cancer, VIN, Vaginal cancer, VAIN, Anogenital warts

Cervical cancer, CIN, AIS

Population approved

Males and females aged 9–26 years

Females aged 9–25 years

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations

Females aged 11 and 12 years with catch-up vaccination for females aged 13–26 years. Permissive for boys aged 9–26 years

Technology used

Yeast

Insect cell substrate

Adjuvant

Amorphous hydroxyphosphate sulfate (Merck and Co., Inc)

Aluminum hydroxide + 3 = deacetylated monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL, Coixa/GSK)

Quadravalent Vaccine: GARDASIL.

FDA approved in 2006.

In 2007 the Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease (FUTURE) II reported results from a randomized, double-blind trial of 12,167 women aged 15–26 years who received Gardasil or placebo. For 3-year follow-up, vaccine efficacy for preventing dysplasia or invasive disease was 98 % in the per-protocol population (44 % for the intention-to-treat population).

FUTURE I was a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 5,455 women aged 16–24 years. Vaccine efficacy for preventing anogenital warts as well as dysplasia or invasive disease associated with HPV types 16 or 18 was 100 %.

In a double-blind, randomized trial of 3,817 women aged 24–45 years, GARDASIL efficacy against infection related to HPV-6, -11, -16, and -18 was 90.5 %.

Merck is currently comparing the efficacy of GARDASIL to a nanovalent HPV vaccine.

Bivalent Vaccine: CERVARIX.

Phase II, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial known as Papilloma TRIal against Cancer In young Adults (PATRICIA) published in 2009. In this study, 18,644 women aged 15–25 years received placebo or were vaccinated with CERVARIX.

Vaccine efficacy against HPV-16 and -18 CIN II–IIII was 92.9 %.

Evidence of cross-protection efficacy.

There has not been a direct head-to-head efficacy trial between GARDASIL and CERVARIX.

Diagnosis

First symptom of early cervical cancer: frequently thin, clear or blood-tinged vaginal discharge usually unrecognized by the patient.

Classic symptom: intermittent, painless metrorrhagia or postcoital spotting, although this is not the most common symptom.

With progression, bleeding becomes heavier, more frequent, and ultimately continuous. Usually if this bleeding occurs in a postmenopausal woman, it leads to earlier medical attention.

Late stage disease involves spread into the parametria or the pelvic sidewalls and causes flank or leg pain, which is usually a sign of involvement of the ureters or sciatic nerve. Bladder or rectal invasion frequently leads to hematuria, rectal bleeding, and possibly vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistula. Lymphedema may be a sign of late stage or recurrent disease due to venous blockage from extensive sidewall disease.

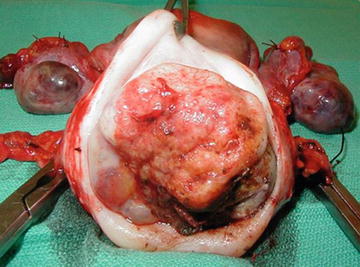

Gross clinical appearance.

Most common: exophytic, large, friable polypoid lesion arising from the ectocervix (Fig. 2.2). These lesions may arise within the endocervcial canal creating a barrel-shaped lesion.

Fig. 2.2.

Gross image of invasive cervical carcinoma (Image provided courtesy of Dr. Krishnansu S. Tewari).

Lesions within the endocervical canal are more commonly adenocarcinomas, which arise in the endocervical mucous-producing gland cells. Because of the origin within the cervix, the lesion may be present for longer time before it is clinically evident.

Firm cervix with little visible ulceration or mass.

An ulcerative tumor that erodes through the cervix.

Screening

Prevention, screening, and early treatment are imperative.

Cervical dysplasia and cancer is slow to progress, able to be diagnosed early with current screening modalities, and almost always cured when diagnosed early.

Late diagnosis most frequently results in incurable disease and death.

Cytology, using the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, and colposcopy are both valuable screening tools.

Cervical cancer screening guidelines according to American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3.

ASCCP cervical cancer screening guidelines.

Population

Screening recommendation

<21 years

No screening

21–29 years

Cytology every 3 years without HPV testing

30–65 years

Cytology and HPV co-testing every 5 years

>65 years

No screening if negative adequate prior screening (as long as no prior history of CIN or cervical cancer)

After hysterectomy

No screening (as long as cervix removed and no prior history of CIN or cervical cancer)

After HPV vaccination

Same as unvaccinated women

Abnormal pap smears may require further workup with colposcopy with possible need for biopsy.

Colposcopy involves use of 5 % acetic acid applied to the cervix and inspection with a colposcope that magnifies the cervix and allows for visualization with color filters.

A satisfactory colposcopy requires that the entire squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) be visualized.

Concerning findings for which biopsy should be obtained:

Acetowhite changes.

Irregular contour.

Atypical vessels.

Coarse mosaicism or punctation.

Large multiquadrant lesions.

An endocervical curettage (ECC) should be done as long as the patient is not pregnant.

Cervical dysplasia or early invasive cervical cancer (Stage IA1) can be treated with loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) or cold knife cone (CKC).

ASCCP guidelines (www.asccp.org) should be used to triage abnormal cytology and histology.

Pathology (Refer to Table 2.4) [4]

Stage | Rate of pelvic lymph node metastases (%) | Rate of para aortic lymph node metastases (%) |

|---|---|---|

I | 15 | 6 |

II | 29 | 17 |

III | 47 | 30 |

There are four main routes of spread of cervical carcinoma:

Direct spread into the vaginal mucosa.

Spread into the myometrium, particularly with lesions originating in the endocervix.

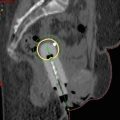

Spread into the paracervical and parametrial lymphatics and then further (primarily: obturator, hypogastric, external iliac, and sacral nodes and secondarily: common iliac, inguinal, and para-aortic nodes) (Fig. 2.3) [4].

Fig. 2.3.

Patterns of lymphatic spread in cervical carcinoma [4]. Reprinted from Clinical Gynecologic Oncology, 7th Edition, Di Saia PJ, Creasman WT. Chapter 3 Invasive Cervical Cancer, Monk BJ, Tewari KS, Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier. Clinical gynecologic oncology by Di Saia PJ, Creasman WT. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier Mosby in the format reuse in a book/textbook via Copyright Clearance Center.

Direct extension into adjacent structures (parametria, bladder, bowel).

Adenocarcinomas arise from the endocervical mucous-producing glands and, because they originate within the endocervical canal, it takes longer until these tumors are clinically evident. This growth pattern results in the classic barrel-shaped cervix.

No difference in survival between cervical adenocarcinomas and squamous carcinomas after correction for stage (see Tables 2.5 and 2.6 [5]).

Stage

Surgery only (%)

Radiation only (%)

Surgery + radiation (%)

Ib1

94.5

80.1

83.6

Ib2

91.4

73.7

76.7

IIa

72.6

64.5

76.2

IIb

73.0

64.2

64.3

Table 2.6.

Histologic types of cervical cancer.

Pathology

Prevalence

Nonglandular

Squamous cell

65–85 %

Verrucous

Rare

Sarcomatoid

Rare

Glandular

Endocervical

10–25 %

Endometrioid

Rare

Clear cell

Rare

Mucinous

Rare

Serous

Rare

Adenoid cystic

Rare

Villoglandular

Rare

Other, mixed epithelial tumors

Adenosquamous

5 %

Glassy cell

Rare

Small cell

Rare

Nonepithelial tumors

Rare

Carcinosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, endometrial stromal sarcoma, germ cell tumors, melanoma, lymphoma, neuroendocrine

1998 FIGO Annual Report of over 10,000 squamous cell carcinomas and 1,138 adenocarcinomas noted no difference in survival in Stage I cancers.

Staging

Cervical cancer is clinically staged based on (Table 2.7):

Table 2.7.

Cervical cancer staging according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) revised in 2009.

FIGO Stage

Description

0

Carcinoma in situ

Ia1

Invasion of stroma <3 mm in depth and ≤7 mm in width

Ia2

Invasion of stroma >3 mm and ≤5 mm in depth and ≤7 mm in width

Ib1

Clinical lesions greater than Stage Ia but no greater than 4 cm

Ib2

Clinical lesions confined to the cervix that are greater than 4 cm

IIa

Involvement of the upper 2/3 vagina

IIb

Involvement of the parametria without sidewall involvement

IIIa

Extension to lower 1/3 vagina

IIIb

Extension to pelvic sidewall or hydronephrosis or non-functional kidney

IVa

Extension to bladder or rectum

IVB

Distant metastasis or disease beyond the pelvis

Exam.

CKC or LEEP.

Imaging—CXR, IVP, CT urogram, Barium enema.

Cystoscopy.

Proctosigmoidoscopy.

PET/CT Staging

In 2005 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approved coverage for FDG-PET for staging newly diagnosed and locally advanced cervical cancers and screening for cervical cancer recurrence.

Sensitivity of PET in detecting pelvic nodal metastases in patients with untreated cervical cancer = 80 %, sensitivity of CT = 48 % [6].

A 2007 meta-analysis of 41 studies concluded that PET/CT had the highest sensitivity (82 %) and specificity (95 %) for detection of positive nodes compared to CT (50 and 92 %) and MRI (56 and 91 %). PET positive nodes have been found to be a prognostic biomarker predicting treatment response, pelvic recurrence risk, and survival [6].

Genetics

There is no known genetic basis for cervical cancer.

Indication for and Modes of Treatment (Surgery/Chemotherapy/Radiation Therapy)

During the past several decades, staging definitions and treatment recommendations for cervical cancer have changed significantly (Table 2.8).

Table 2.8.

Treatment of cervical cancer by stage.

Stage

Standard treatment

Fertility preserving treatment

IA1, −LVSI

Extrafascial hysterectomy

Cervical cone biopsy

IA1, +LVSI

Extrafascial hysterectomy, +/− pelvic lymph node dissection

Cervical cone biopsy and laparoscopic pelvic lymph node dissection

IA2, occult IB1

Modified radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection, +/− adjuvant therapy

Radical trachalectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection

IB1, IB2, IIA

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access