Case 80

Presentation

A 72-year-old woman with a history of diffuse osteopenia presents to your office after she was seen by her primary medical doctor and found to have elevated serum calcium on routine blood screening. Bone densitometry reveals the bone mineral density of the L2-L4 spine to be 2.2 standard deviations below age-matched controls.

She denies a history of nephrolithiasis, pathologic fractures, pancreatitis, peptic ulcer disease, fatigue, or depression. She does admit to occasional back pain. There is no family history of endocrinopathies, and she denies irradiation to her neck. On examination, there are no palpable masses in the neck. The serum calcium is 10.6 (normal, 8.5 to 10.4) mg/dL, and her corresponding intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) level is 145 (normal, 10 to 65) pg/mL.

Differential Diagnosis

Contemporary series of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism are dominated by elderly women with mild to moderate degrees of hypercalcemia and few, if any, overt symptoms and signs of the disorder. These patients often have nonspecific symptoms such as depression, decreased cognitive ability, myalgias, and arthralgias. The women often exhibit mild skeletal complications of hyperparathyroidism (osteopenia or osteoporosis) and have a very low incidence of renal stones. Prospective analyses have suggested that even apparently asymptomatic patients with hyperparathyroidism may have subtle psychiatric symptoms, which can be reversed by treatment.

Among the differential diagnoses for hypercalcemia in an elderly woman, primary hyperparathyroidism is the most likely explanation. However, it is important to establish the biochemical diagnosis with additional testing and to exclude other possible diagnoses, including secondary hyperparathyroidism, benign familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (BFHH), malignancy (i.e., squamous cell, breast, or colon cancers), granulomatous disease (i.e., sarcoidosis, tuberculosis), and dietary (i.e., large amounts of supplemental calcium or vitamin D, yogurt and antacids, or betel nuts) and pharmacologic (i.e., lithium, thiazide diuretics) causes.

The most common pathologic cause of primary hyperparathyroidism is a parathyroid adenoma (85%). Adenomas are benign and typically affect only one gland, but in 5% of cases, there are two. Primary hyperparathyroidism is more frequent in women than in men, at a ratio of 3:1. Macroscopically, the affected adenoma is enlarged, tan-brown, ovoid, encapsulated, and occasionally has areas of hemorrhage or cystic spaces. Histologically, they are composed of cohesive sheets of chief cells, oncocytic cells, transitional oncocytic cells, or a mixture of these cells.

Parathyroid hyperplasia affects all glands and is the underlying cause of primary hyperparathyroidism in 10% of cases. It can be associated with the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) 1 and 2a syndromes. MEN 1 includes hyperparathyroidism, pituitary adenoma, and pancreatic tumors (most commonly gastrinomas or insulinomas). MEN 2a includes hyperparathyroidism, medullary carcinoma of the thyroid, and pheochromocytoma. Parathyroid carcinoma is a rare (<1% of cases) cause of primary hyperparathyroidism.

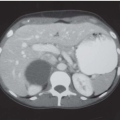

The biochemical diagnosis is established with elevated serum calcium, elevated iPTH, normal blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (to exclude secondary hyperparathyroidism), and normal or elevated 24-hour urinary calcium (to exclude BFHH). After the diagnosis is established, noninvasive preoperative imaging should be performed to facilitate minimally invasive parathyroidectomy (MIP). Localization can include Sestamibi-technetium 99 (Tc 99m) scintigraphy, ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). There is a general consensus that the single best study is Sestamibi, especially when combined with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

Sestamibi scan utilizes Tc 99m, which diffuses into cells and concentrates in the mitochondria. Parathyroid adenomas have a generous blood supply, high metabolic rate, and an absence of p-glycoprotein on the cell surface, which allows for a rich uptake of Tc 99m. When combined with SPECT, Sestamibi is an especially powerful tool, because it allows for three-dimensional localization. Ultrasound of the neck is often combined with Sestamibi to exclude underlying thyroid abnormalities, which can distort Sestamibi findings. The combined specificity of the two studies is 90%.