Case 61

Presentation

A 53-year-old minister presents to your office with a 7- to 8-month history of swelling and bruising of the right posterior thigh. There was initial improvement in the ecchymosis, but the mass persisted and then recently increased in size. He denies any neurovascular symptoms in the right lower extremity. Examination of the right lower extremity reveals a 21 × 17-cm mass in the distal aspect of the right thigh. The distal aspect of the mass can be felt at the level of the popliteal fossa. The femoral and the dorsalis pedis pulses are palpable.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a soft-tissue mass includes benign lesions such as lipomas, leiomyomas, neuromas, lymphangiomas, and soft-tissue sarcomas. Besides sarcomas, other malignant lesions (e.g., primary or metastatic carcinoma, melanoma, or lymphoma) should also be considered.

Discussion

Soft-tissue sarcomas represent a diverse histologic group of rare tumors, but they share a common embryonic origin, the mesoderm. Exceptions include neurosarcomas, Ewing sarcoma, and peripheral neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) that arise from the ectoderm. Of particular note, although more than 75% of the human body weight consists of soft tissue skeleton, these tumors comprise only 1% of adult malignancies and 15% of all pediatric malignancies. In 2004, approximately 8,680 new cases were expected to have been diagnosed in the United States, with 3,660 deaths, thus underscoring the relatively high overall mortality associated with this malignancy. Soft-tissue sarcomas can occur anywhere in the body but most commonly originate in the extremities (upper extremity, 13%; lower extremity, 32%), the trunk (19%), the retroperitoneum (15%), or the head and neck (9%).

Case Continued

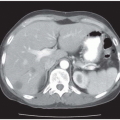

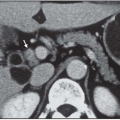

Given the antecedent history of local trauma, the primary care physician orders an ultrasound scan, which demonstrates a mass in the posterior thigh measuring 9 × 5 cm that was thought to be a hematoma. Subsequently, due to continued increase in size of the mass, a computed tomography (CT) scan is obtained, which reveals a 12 × 12-cm mass with areas of central necrosis. Prior to referral to the tertiary center, an incisional biopsy is performed, which reveals a high-grade leiomyosarcoma.

Diagnosis and Recommendation

Pretreatment radiologic imaging provides valuable information that aids in the diagnosis by defining the local extent of the tumor, which also assists in local staging of the disease and planning of the biopsy. Plain radiographs are useful for providing information on primary bone tumors, but are not as useful for evaluating soft-tissue tumors of the extremities, except for chronic hematomas for which they may reveal diagnostic calcification. Ultrasonography is also of limited value, except to guide percutaneous biopsies. The current imaging modalities of choice are either contrast-enhanced CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and the debate continues regarding which one is superior. A large multi-institutional trial by the Radiology Diagnostic Oncology Group compared these modalities, correlated their interpretations of the histologic and intraoperative findings, and found no statistical differences. Nevertheless, MRI is the preferred imaging modality for extremity sarcoma because it can provide multiplanar images with better spatial orientation. It also has the advantage of permitting concurrent MR angiography, which allows delineation of the tumor’s relationship to adjacent vascular structures. Behavior of the primary tumor following administration of gadolinium contrast allows differentiation from lipomatous benign tumors. Dynamic postcontrast images may also facilitate differentiating viable tumor in adjacent muscle from tumor-associated edema. For low-grade sarcomas, chest radiography should be performed to look for lung metastases, while CT of the chest should be considered for patients with high-grade sarcomas or tumors larger than 5 cm.

To establish a histologic diagnosis, fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) may be used at centers where experienced cytopathologists are available. The diagnostic accuracy of FNAB in finding sarcomas ranges from 60% to 96%. If tumor grading is essential for treatment planning, then FNAB has limitations due to the small amount of material obtained. Office-based core needle biopsy has a diagnostic accuracy of about 95%, and its yield can be further enhanced by the use of ultrasonography to avoid sampling necrotic and cystic areas, and importantly avoiding neurovascular bundles that may have been displaced superficially. The core biopsy provides enough tissue to establish a histologic diagnosis and tumor grade, and in difficult cases allows additional diagnostic tests, such as electron microscopic examination and cytogenetic analysis. It also has an advantage over open biopsies, which can delay preoperative radiation therapy, and are particularly fraught with wound complications, particularly if the tumor is very large and primary closure can be under tension. If a core biopsy reveals nondiagnostic material, then an incisional biopsy can be performed, but should ideally be part of a well-planned treatment strategy. With a history of a rapidly growing soft-tissue mass, mass larger than 5 cm, and all the deep lesions (deep to the superficial fascia), the clinician should maintain a high degree of suspicion for the possibility of a sarcoma. When performing a biopsy, proper placement of the incision is vital, and it should be performed at a site that can be excised en bloc during the definitive surgery resection. Transverse incisions in the extremities are always contraindicated. The principles of incisional biopsy are as follows: (a) use a small longitudinal incision; (b) avoid flaps; (c) do not expose neurovascular structures; (d) sample the peripheral tumor, which is the most viable representative of the diagnostic portion; (e) avoid crushing the specimen with forceps; (f) obtain frozen section to determine adequacy of the sample; (g) achieve meticulous hemostasis; (h) avoid suction drains; (i) close the wound carefully to prevent necrosis or ulceration of the skin; and (j) biopsy tracks should not traverse normal anatomical muscular skeletal compartments.

Recommendation

Obtain an MRI scan with MR angiogram to determine proximity of the tumor to the neurovascular bundle, as well as determine vessel patency. Obtain CT scan of the chest to exclude metastatic disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree