Case 57

Presentation

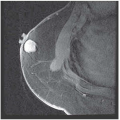

A 39-year-old woman underwent a routine screening mammogram and is found to have clustered microcalcifications in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast. The patient’s mother had undergone a mastectomy for “breast cancer” at age 47 and is alive and free of disease. There is no other family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Review of systems and physical examination are normal. There is no palpable breast mass or axillary/supraclavicular lymphadenopathy.

Differential Diagnosis

The analysis of microcalcifications can be challenging. If they are scattered, the most important determination is whether or not there are casting calcifications present. If so, malignancy cannot be excluded. If clustered, then analysis of their form becomes critical. Teacup or pearl-type calcifications are benign. Granular or casting calcifications are malignant. Clustered calcifications that appear obviously malignant or highly suspicious for malignancy warrant a biopsy whether or not an associated mass is clinically palpable. Some of the pathological entities that can cause calcifications include ductal ectasia, fat necrosis, atypical ductal hyperplasia, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and invasive carcinoma with extensive intraductal component (EIC). If calcifications are obviously benign, then routine follow-up at 4- to 6-month intervals is recommended if there is a high probability that they are benign. Otherwise, biopsy should be performed at the discretion of the clinician.

Discussion

Cancer cells are classified as in situ or invasive depending on whether or not they invade through the basement membrane. Broder’s original description of in situ breast cancer stressed the absence of invasion of cancer cells into the surrounding stroma and their confinement within natural ductal and alveolar boundaries. Because areas of invasion may be minute, the accurate diagnosis of in situ cancer necessitates the analysis of multiple microscopy sections to exclude invasion. In 1941, Foote and Stewart published a landmark manuscript, which distinguished lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) from DCIS. In the late 1960s, Gallagher and Martin published a descriptive study of whole breast sections and described a stepwise progression from benign breast tissue to in situ cancer and subsequently to invasive cancer. They coined the term minimal breast cancer (LCIS, DCIS, and invasive cancers smaller than 0.5 cm in size) and stressed the importance of early detection.

DCIS accounts for 20% of all breast cancers in women and up to 5% of breast cancers in men. It occurs most commonly in the fifth decade of life. The term intraductal carcinoma is frequently applied to DCIS, which carries a high risk for progression to an invasive cancer. DCIS is suspected when clustered microcalcifications are detected on screening mammogram. These clusters demonstrate pleomorphic or fine, linear, and branching microcalcifications. Palpable DCIS tumors have been described, but these are uncommon. DCIS presents as a single lesion (unifocal DCIS) or as multiple lesions, which may be limited to one quadrant of the breast (multifocal DCIS) or may involve two or more quadrants (multicentric DCIS).

Before the widespread use of mammography, diagnosis of breast cancer was by physical examination. At that time, in situ cancers constituted approximately 5% of all breast cancers and, by a ratio of more than 2:1, LCIS was diagnosed more frequently than DCIS. However, now that screening mammography is widely utilized, a 10-fold increase in the incidence of in situ cancer (50%) has been seen and, by a ratio of more than 2:1, DCIS is more frequently diagnosed than LCIS.

Tissue for histological diagnosis can be obtained by percutaneous stereotactic core biopsy. However, negative core biopsy of a suspicious mammography lesion should be followed by confirmatory needle-localization excisional biopsy to avoid diagnostic failure secondary to sampling error. Similarly, a stereotactic core biopsy diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia should result in a confirmatory needle-localization excisional biopsy to avoid missing associated DCIS.

Specific classification of DCIS is problematic because of tumor heterogeneity and interobserver variation in histological classification. However, two broad categories for DCIS are agreed upon: comedo and noncomedo types. DCIS is classified as comedo type based on the presence of necrotic cellular debris within the ducts, the presence of numerous mitoses and large pleomorphic nuclei, and the absence of specific architectural changes.

Recommendation

Compression mammography is recommended for this patient to further characterize the microcalcifications. Stereotactic core biopsy is recommended to establish tissue diagnosis. However, if this is not available, then a needle-localized excisional breast biopsy should be performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree