Case 47

Presentation

A 52-year-old white woman is referred to your office with a 4-week history of pruritus, jaundice, and dark urine. The patient denies abdominal pain but noted intermittent nausea without vomiting. She has mild anorexia with a 10-pound weight loss over the past 4 weeks. She denies any change in bowel habit or hematochezia but reports pale stools. There is no prior history of these symptoms. Patient had previously undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy. On physical examination, the patient has icteric sclera, but does not appear cachectic or in any acute distress. There are scratch marks on her extremities and trunks from the pruritus. Her abdomen is soft, nontender, and nondistended with no evidence of intra-abdominal masses or hepatosplenomegaly.

Differential Diagnosis

The presence of progressive painless jaundice with associated constitutional symptoms points toward a malignant neoplasm of the extrahepatic biliary tree, head of the pancreas, or ampulla of Vater. Given the prior history of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, benign biliary stricture or choledocholithiasis should also be considered. Injury resulting from the laparoscopic cholecystectomy would have presented soon after the operative procedure period. Although only about 10% of patients with postoperative strictures are actually suspected within the first week after cholecystectomy, nearly 70% of patients are diagnosed within the first 6 months, and over 80% within 1 year of surgery. In the remaining patients, presentation may be delayed for many years after the initial operative procedure. However, patients with postoperative bile duct strictures who present months to years after the initial operation frequently have evidence of repeated episodes of cholangitis. Less commonly, patients may present with painless jaundice and no evidence of sepsis.

Recommendation

Obtain liver function tests, complete blood count, and coagulation studies. The first imaging test recommended is abdominal ultrasonography, which can be subsequently complemented with computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis for further anatomical definition of the hepatobiliary and pancreatic system.

▪ Ultrasonogram

Ultrasonography Report

There is a dilated bile duct extending throughout the right and left hepatic lobe emanating from the porta hepatis. There is a hypoechoic mass at the portal bifurcation and extending toward the left hepatic duct. The common bile duct is of normal caliber and does not contain any stones. The gallbladder is not distended and does not show evidence of wall thickening.

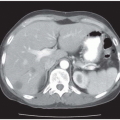

Case Continued

Liver function test results are total bilirubin 24.9, alkaline phosphatase 336, ASD 82, albumin 2.7, and cancer antigen (CA) 19.9: 64,154. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis reveals the presence of a hepatic duct confluence mass, which is confirmed with associated dilated intrahepatic biliary tree. There is no evidence of suspicious lymphadenopathy.

Diagnosis and Recommendation

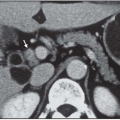

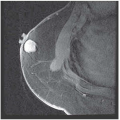

The clinical, laboratory, and radiologic studies strongly indicate the presence of a hilar cholangiocarcinoma with possible extension to the left hepatic duct. To further delineate the extent of local disease, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is traditionally obtained. However, recent developments in magnetic resonance (MR) technology allow detailed noninvasive imaging of the biliary tree, that is, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography (MRCP). It also provides additional valuable information regarding parenchymal involvement by tumor, nodal metastasis, and vascular invasion. On the other hand, PTC has the advantage of allowing concurrent placement of a biliary stent for relief of jaundice and also obtaining brushings to establish a tissue diagnosis. However, it should be stated that if the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicates that the presumed hilar cholangiocarcinoma is judged to be resectable, then a percutaneous cholangiogram or tissue diagnosis is not necessary, because it does not influence the choice of resection.

The presence on ultrasound scan and MRI of a 4.5-cm mass in the patient with a history of jaundice supports the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma that may have initially arisen in the left or the right biliary tree before extending to the confluence, at which time jaundice appears. When the tumor arises in the confluence of the common hepatic duct (type 1 and 2), the mass is much smaller at the time of presentation with jaundice. The greatly dilated intrahepatic branches on the left and some degree of atrophy of the left lobe (segment II and III) are in favor of the initial location of this tumor to be on the left side with subsequent extension to the confluence. This pattern of progression provides orientation to the treatment approach: no drainage of the left duct is necessary because it is not

functional, and the appropriate option is to manage with resection by means of a left hemihepatectomy (segment II, III, IV, and segment I).

functional, and the appropriate option is to manage with resection by means of a left hemihepatectomy (segment II, III, IV, and segment I).

Discussion

Bile duct cancers are very uncommon tumors. In autopsy series, the incidence ranges from 0.01% to 0.2%. The frequency of proximal bile duct carcinomas ranges from 1 in 40,000 to 4 in 100,000. In the United States, approximately 4,500 tumors of the extrahepatic bile duct occur each year, and of these, 2,500 are limited to the confluence of the hepatic duct. Cholangiocarcinomas located at the hepatic duct bifurcation are known as Klatskin tumors, named after Dr. Klatskin who described this condition in 1965. Bile duct cancers have a slight male predominance and occur primarily in older individuals, with a median age of 70 years at diagnosis. The risk of developing bile duct cancer is distinctly elevated in patients with ulcerative colitis. Patients with ulcerative colitis have an incidence 9 to 22 times higher than that of the general population, and predisposition is independent of whether patients have had adequate therapy of their inflammatory colonic disease. Although there is an association between bile duct cancers and gallstones, no clear causal relationship has been demonstrated. Chronic infections, such as Clonorchis sinensis infection, have been shown to increase the risk of developing bile duct cancer. Other risk factors include sclerosing cholangitis, choledochal cysts, and congenital hepatic fibrosis.

About 90% of malignant bile duct tumors are adenocarcinomas. These tend to grow very slowly, and the pattern of spread is most frequently by local extension, though 30% may develop nodal metastasis. Distal metastases are seen less frequently than in other cancers. Morphologically, these tumors are described as nodular, papillary, sclerosing, or diffusely infiltrating with the nodular variant being the most frequent variety. Longmire proposed a classification according to location, with 60% occurring in the upper third of the ductal system, which includes the confluence of the hepatic ducts. The middle third is located between the cystic duct and the upper part of the duodenum. Finally, the lower third is located between the upper border of the duodenum and up to, but not including, the ampulla of Vater. The hilar cholangiocarcinomas are further classified into four types according to Bismuth: type 1, common hepatic duct to the level of the confluence; type 2, extension to the confluence of the hepatic duct up to the communication between the two branches; type 3, extension into either the right or left hepatic duct; and type 4, extension into both the right and left hepatic ducts. The distinct morphologic varieties also show a pattern of occurrence; the nodular variety commonly occurs in the upper duct and presents as a small localized mass. The papillary lesions seldom present in the hilar region, but are commonly seen in and near the ampulla and may be multifocal. The diffusely infiltrating variant presents as a thickening or an extensive area of the extrahepatic biliary tree, and can be difficult to distinguish from sclerosing cholangitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree