Case 44

Presentation

A 56-year-old man is referred to your office by his primary care physician for evaluation of a rising carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level. Two years previously, the patient underwent a sigmoid colectomy for a T3 N1 (American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] stage III) colon cancer, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and leucovorin. At that time, he had no evidence of metastatic disease. Recently, he has been found on routine follow-up to have an elevated CEA level (19.2 mg/dL).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for liver lesions commonly includes hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, hepatic adenoma, metastatic tumor, hemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), and a benign cyst.

Discussion

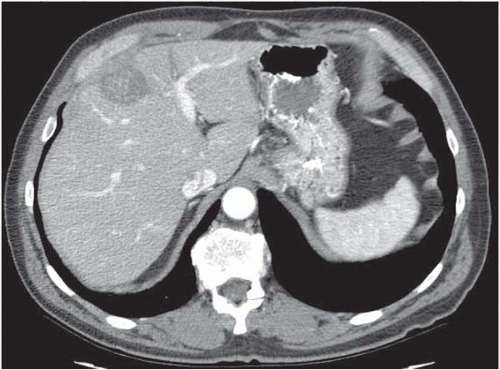

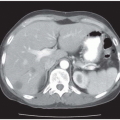

A computed tomography (CT) scan using a quadphase liver protocol is currently the study of choice to evaluate liver tumors at most institutions. In a

patient with a history of colorectal cancer with an elevated CEA level, and with CT findings consistent with metastatic colon cancer (low-attenuation irregular lesion with punctate calcifications), the diagnosis is all but certain. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is not routinely indicated for a tissue diagnosis if surgical exploration is contemplated. A negative biopsy will not alter management if there is no evidence of metastatic carcinoma elsewhere.

patient with a history of colorectal cancer with an elevated CEA level, and with CT findings consistent with metastatic colon cancer (low-attenuation irregular lesion with punctate calcifications), the diagnosis is all but certain. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is not routinely indicated for a tissue diagnosis if surgical exploration is contemplated. A negative biopsy will not alter management if there is no evidence of metastatic carcinoma elsewhere.

Case Continued

The CT scan demonstrates a single tumor in the medial segment of the left lobe (segment IV). A chest x-ray shows no evidence of metastatic lesions, and a colonoscopy demonstrates no recurrence or new primary.

Case Continued

The patient has no other significant medical problems, takes no medications, and reports good exercise tolerance. Laboratory studies, including platelet count, total bilirubin, and prothrombin time, are normal.

Diagnosis and Recommendation

The patient has metastatic colorectal cancer, which appears to be confined to the liver. He is a good operative candidate, and should be offered exploratory laparotomy. If there is no evidence of disease outside the liver upon surgical exploration, he will undergo resection and/or ablation of the metastatic tumor.

▪ Approach

Hepatic resection remains the only potentially curative intervention for these patients as long as R0 resection can be achieved while preserving adequate functional residual liver volume. If additional lesions are discovered during resection, these can either be resected or destroyed with radiofrequency ablation. The role of postresection adjuvant hepatic intra-arterial chemotherapy is uncertain, particularly given the recent availability of new systemic chemotherapeutic and biologic agents that appear to yield significantly improved response rates compared to traditional agents (e.g., 5-FU). Hepatic intra-arterial chemotherapy, at this time, should not be routinely used outside of clinical trials.

Discussion

The American Cancer Society estimated that approximately 150,000 cases of colorectal cancer would be diagnosed in 2004 in the United States. One fourth of these were expected to have hepatic metastases at presentation (synchronous metastases), and another quarter were expected to develop hepatic metastases during the course of their disease (metachronous metastases). The median survival time for patients with untreated (but potentially resectable) hepatic metastases is on the order of 14 to 18 months, with essentially no survivors beyond 3 years.

Initially, metastasectomy for colorectal liver metastases was met with some skepticism, given the morbidity of liver resection historically and the perception that liver metastases were a harbinger of widespread disease. However, since the initial reports in the early 1980s, mounting data have supported an aggressive approach. Specialized centers consistently report 5-year survival rates after metastasectomy of 30% to 50% with a perioperative mortality of less than 5%. Similar to other complex surgical procedures, outcome closely correlates with the case volume performed at a given medical center. Therefore,

evaluation and treatment of these patients should be performed at centers where the staff—surgical, anesthesia, interventional radiology, oncology, intensive care unit, and nursing—routinely care for patients who undergo major hepatic resections.

evaluation and treatment of these patients should be performed at centers where the staff—surgical, anesthesia, interventional radiology, oncology, intensive care unit, and nursing—routinely care for patients who undergo major hepatic resections.

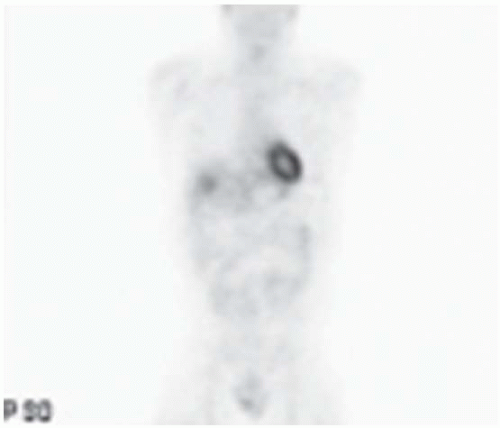

The curative resection of metachronous colorectal liver metastases is generally predicated on the absence of metastases outside the liver. Routine evaluation therefore includes plain radiographs of the chest to identify possible pulmonary metastases. Chest CT scan only minimally improves detection of metastatic lesions in a patient with negative chest radiographs and has a high false-positive rate, and is therefore not routinely utilized. Either colonoscopy or barium enema is essential to rule out recurrence at the anastomosis or metachronous primary colonic tumors. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (quadphase liver protocol) allows careful evaluation of the liver, as well as the remainder of the abdomen, for nodal disease or evidence of carcinomatosis. Helical CT scan also allows three-dimensional volumetry, which assists in operative planning to ensure adequate hepatic reserve after resection. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is sometimes used as an alternative to delineate hepatic tumors and provide detailed information about the relation of a tumor to vascular and biliary structures. However, MRI is less useful for evaluating the remainder of the abdomen and is more expensive than CT. Whole-body PET, though not mandatory, is used with increasing frequency. PET is the most specific imaging modality in cases of uncertain hepatic lesions, and is especially useful for detecting extrahepatic disease, although its sensitivity is probably not greater than that of CT for liver lesions. Bone scans are not indicated in the absence of bony symptoms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree