Case 43

Presentation

A 39-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician. She has a history of intermittent upper abdominal pain but is otherwise healthy. There is no history of nausea, vomiting, or troublesome heartburn. Past medical history is essentially unremarkable except for migraines. Her medications include ibuprofen for her headaches and oral contraceptive pills for the past 5 years. The primary care physician orders an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and right upper quadrant ultrasound. Upper GI endoscopy reveals antral gastritis with biopsy positive for Helicobacter pylori. She is started on an anti-H. pylori regimen. Ultrasound shows no evidence of gallstones but an incidental finding of a 1.5-cm solid hypoechoic mass. The patient’s symptoms resolve with the anti-H. pylori regimen, and she is referred for further evaluation of the solid hepatic mass.

Differential Diagnosis

Disease processes that may present as a hepatic mass can be broadly categorized into benign and malignant conditions. A variety of benign liver tumors have been described, but the common lesions include hemangiomas, hepatic adenomas, focal nodular hyperplasia, and bile duct hematomas. In the malignant category, primary malignancies include hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and angiosarcoma. Malignancy can also include metastatic disease from an extrahepatic primary tumor.

Discussion

Solid hepatic lesions often create a diagnostic challenge, and management should incorporate a cost-effective diagnostic and therapeutic approach. The first step involves a careful history and physical examination with attention given to constitutional and gastrointestinal symptoms, with particular attention to prior exposure to hepatitis, carcinogens, or oral contraceptives. Physical examination should be directed at outlining any stigmata of chronic liver disease. Careful examination of the skin, eyes, and breast, as well as a pelvic and rectal examination should be performed to identify sources of primary tumor that may have metastasized to the liver. Laboratory tests include a complete blood cell count, coagulation profile, liver function tests, hepatitis A, B, and C screen, and measurement of serum tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9).

Many hepatic lesions can have overlapping radiographic features, causing a diagnostic dilemma. The ultrasound findings of focal liver lesions are frequently nonspecific, making differentiation between benign and malignant liver lesions problematic. The limitations of ultrasound scan include its dependence on the operator and patient limitations

such as obesity and biliary tree distention. Prior to the development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the diagnostic algorithm included obtaining nuclear medicine examinations, such as tagged red blood cell (RBC) scan to detect liver hemangiomas, and Tc-sulfur colloid scan (which enhances Kupffer cells) to distinguish focal nodular hyperplasia, which contains Kupffer cells, from hepatic adenoma, which contains hepatocytes. Spiral computed tomography (CT) scans with three-phase (arterial, portal, and parenchymal) images are obtained to categorize the vascularity of the various lesions according to the timing of the contrast bolus. With experience gained in bolus injection techniques, characteristic patterns of enhancements can be used to suggest a particular diagnosis, though no specific CT criteria can distinguish benign from malignant liver masses with absolute certainty. Many investigators have demonstrated that the sensitivity and accuracy of MRI in the detection and categorization of liver lesions exceed those of ultrasound scan and spiral CT. Unenhanced MRI helps the diagnosis of focal liver lesions because of the excellent information on morphology provided by T2-weighted and T1-weighted sequences. A variety of contrast media, including gadolinium, hepatobiliary, and tissue-specific MR contrast agents, have been investigated to improve the differential diagnostic potential of this modality. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has become an important tool in the staging of malignancies, but its role in evaluating solid hepatic lesions remains to be defined.

such as obesity and biliary tree distention. Prior to the development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the diagnostic algorithm included obtaining nuclear medicine examinations, such as tagged red blood cell (RBC) scan to detect liver hemangiomas, and Tc-sulfur colloid scan (which enhances Kupffer cells) to distinguish focal nodular hyperplasia, which contains Kupffer cells, from hepatic adenoma, which contains hepatocytes. Spiral computed tomography (CT) scans with three-phase (arterial, portal, and parenchymal) images are obtained to categorize the vascularity of the various lesions according to the timing of the contrast bolus. With experience gained in bolus injection techniques, characteristic patterns of enhancements can be used to suggest a particular diagnosis, though no specific CT criteria can distinguish benign from malignant liver masses with absolute certainty. Many investigators have demonstrated that the sensitivity and accuracy of MRI in the detection and categorization of liver lesions exceed those of ultrasound scan and spiral CT. Unenhanced MRI helps the diagnosis of focal liver lesions because of the excellent information on morphology provided by T2-weighted and T1-weighted sequences. A variety of contrast media, including gadolinium, hepatobiliary, and tissue-specific MR contrast agents, have been investigated to improve the differential diagnostic potential of this modality. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has become an important tool in the staging of malignancies, but its role in evaluating solid hepatic lesions remains to be defined.

Recommendations

Perform liver function tests, hepatitis profile, and measurements of tumor markers including AFP, CEA, and CA 19-9, followed by a contrast-enhanced MRI of the liver.

Case Continued

The liver function tests are normal and the hepatitis profile was nonreactive. None of the tumor markers were elevated.

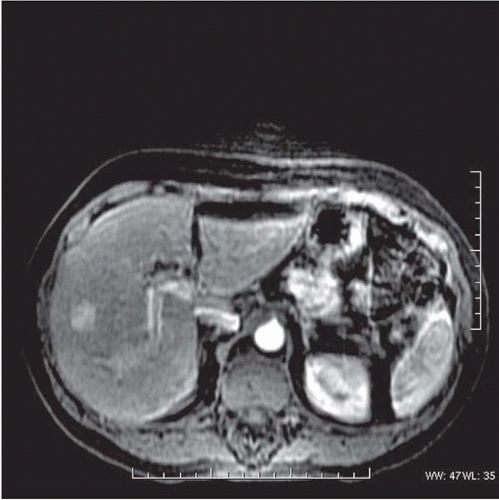

▪ MRI

MRI Report

There is a well-demarcated hypervascular hepatic lesion with indistinct hypodense areas suggestive of a focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), though a hepatic adenoma cannot be excluded.

▪ Approach

In the case of solid hepatic tumors without clinical evidence of malignancy or serum elevation of tumor markers, a benign lesion must be considered during the differential diagnosis, most frequently hemangioma, FNH, or hepatic adenoma. Although not specific, findings of an avascular central scar or a feeding artery to the mass are highly supportive of FNH, and the presence of intralesional hemorrhage with necrosis is similarly supportive of hepatic adenoma. The possible presence of fibrolamellar hepatoma should be kept in the differential diagnosis because the clinical and biochemical characteristics of this carcinoma are nonspecific and the appearance of tumor on imaging may mimic FNH.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree