Case 34

Presentation

A 38-year-old otherwise healthy white man who has suffered from constipation, painful defecation, and anal/rectal bleeding for several months is referred to your clinic. At admission he complains about weight loss and fatigue for over a month. There is no family history of colorectal cancer (CRC).

Digital rectal examination is painful, and allows detection of a solid and fixed rectal mass 4 cm above the anal verge (i.e., at the upper border of the anal canal). Anal sphincter pressures at rest and under squeezing are clinically within the normal range. A slight anemia is present.

Differential Diagnosis

Constipation is a common complaint, but when associated with symptoms such as painful defecation, anorectal tenesmus, anal bleeding, or sudden change in bowel habits, it should promptly lead to a diagnostic workup. In many patients, hemorrhoidal disease may be found to be the source of bleeding, with constipation having developed secondary to painful defecation. CRC does usually present with occult blood loss rather than hematochezia, but rectal carcinoma or advanced primaries of the colon can also lead to lower intestinal bleeding. In young patients without a family history of CRC or other risk factors, symptomatic therapy may be considered; however, in patients over the age of 45 years, especially with a change in bowel habits, colorectal cancer must be excluded.

Discussion

Because sporadic CRC rarely occurs before the age of 45 (see also Case 33), hereditary CRC should be considered in the present case. Therefore, family history must be carefully assessed. The Amsterdam criteria may help to identify families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). These criteria are fulfilled if three first-degree relatives experienced CRC, if at least two generations are involved, and if one of these three patients is younger than 50 years old. Any suspicion should be verified by genetic testing of the patient and, if genetic testing results are positive, all first-degree relatives. The consequence of a positive genetic test in relatives is colonoscopy starting at the age of 25 and repeated within short intervals (1 to 2 years). If HNPCC or multiple polyps are present, subtotal or total colectomy should be recommended. In our case, the family history and the Amsterdam criteria are negative.

In distal rectal carcinoma, changes in stool form, anorectal tenesmus, or painful defecation are typical. Other symptoms such as pelvic or back pain, malaise, or total mechanical obstruction are less frequent and often indicate advanced disease.

Digital rectal examination is the initial diagnostic tool and is crucial to estimate tumor size, location, and relation to the surrounding structures such as the sphincter muscle. Rigid or flexible proctosigmoidoscopy is used to visualize the tumor, to take biopsies for histologic confirmation of the suspected diagnosis, and to give an accurate measurement of the distance of the tumor from the anal verge.

To determine local tumor margins and the depth of infiltration as well as to evaluate mesorectal lymph node metastases, patients should undergo endorectal ultrasound examination (EUS) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), including endorectal MRI. Computed tomography (CT) is less accurate than EUS and MRI for assessing locoregional tumor spread, especially when the primary is located in the distal part of the rectum. However, CT scan is the best means of evaluating distant metastasis, with special attention to the liver, the lungs, the locoregional lymph nodes, and the peritoneal cavity. Liver ultrasound is a reliable alternative to detect liver metastasis, particularly if any question remains after reviewing the CT scan. However, the liver can also be evaluated effectively with intraoperative ultrasound. In distal (and mid-) rectal cancer, pulmonary metastasis may be present as the sole distant metastasis because venous drainage does not entirely follow the splanchnic pathway but may bypass the portal vein through the hemorrhoidal venous plexus and the iliac veins. The tumor markers carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 19-9 should not be used as screening tools, but have proved valuable in monitoring for tumor recurrence

during routine follow-up if the markers were elevated preoperatively.

during routine follow-up if the markers were elevated preoperatively.

Recommendation

Biopsies of the primary tumor should be sent for histologic analysis. Complete flexible colonoscopy should be performed to exclude a synchronous secondary colon cancer.

Case Continued

Histology of the biopsies of the rectal primary reveals moderately differentiated carcinoma of the rectum. Colonoscopy reveals a polypoid, partially ulcerated tumor that involves one third of the rectal circumference and is located on the left side. Apart from the known rectal carcinoma, the remaining colonic mucosa is normal.

Diagnosis and Recommendation

Distal rectal adenocarcinoma. Perform endorectal ultrasound, and CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis for local staging and to exclude distant metastases. Determine preoperative CEA level for comparison in follow-up examinations.

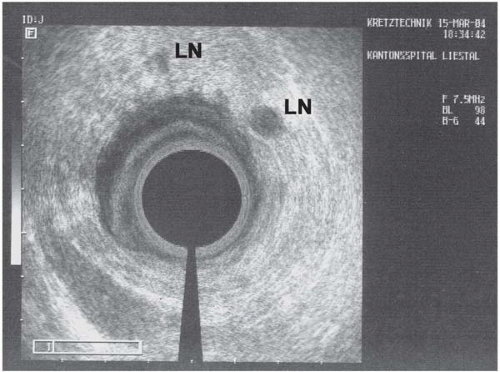

▪ Endorectal Ultrasonographic Image

Endorectal Ultrasonography Report

Hypodense 4-cm large rectal tumoral mass (M) penetrating all layers of the rectal wall (RW) and infiltrating the mesorectum (arrow). No evidence of tumor spread into the prostate, vesicles, pelvic floor, or anal sphincter. Several enlarged mesorectal lymph nodes (LN) up to larger than 10 mm, suspicious for lymph node metastasis.

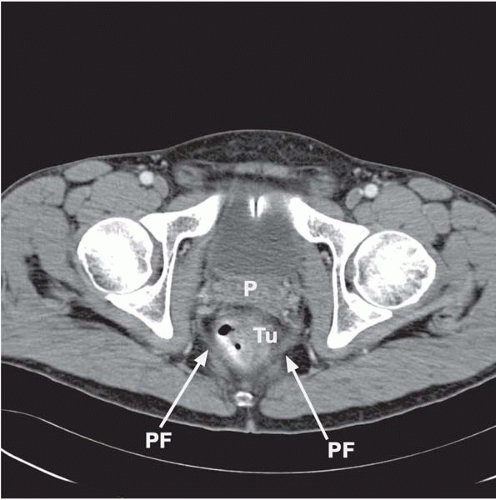

▪ CT Scans

Figure 34.2A

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|