Case 31

Presentation

A 65-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presents to the emergency department with a several-week history of increasing abdominal pain, vomiting, distension, bloating, and worsening constipation. She admits to a 20-lb weight loss over the past 2 months.

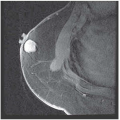

▪ Clinical Photograph

Physical Examination Report

On physical examination, she has no tenderness but her abdomen is markedly distended. Her vital signs are normal and she is afebrile. She denies a family history of colon carcinoma or polyps and has never undergone a colonoscopy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of left-sided colonic obstruction includes carcinoma, incarcerated hernia, inflammatory bowel disease, extrinsic compression from noncolonic pathology (i.e., ovarian cancer), volvulus, fecal impaction, anastomotic stricture, colonic pseudo-obstruction, constipation with megacolon, intussusception, and stricture from diverticulitis or ischemic colitis. In this case, the insidious onset of symptoms over several weeks indicates a chronic process involving neoplasia, stricture, or megacolon. The most common cause (78%) of large bowel obstruction in adults is adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum.

Discussion

Patients with chronic large bowel obstruction complain of pain, distension, and constipation over several weeks. The distension is progressive dilation of the proximal large bowel by the closed-loop obstruction formed by a competent ileocecal valve. Because of the chronicity of this process, ischemia and gangrene of the cecum in association with tenderness and leukocytosis are usually absent. Vomiting is a late manifestation accompanying complete obstruction or involvement of the small bowel. Peritonitis may result from perforation at the site of the obstruction or of the cecum.

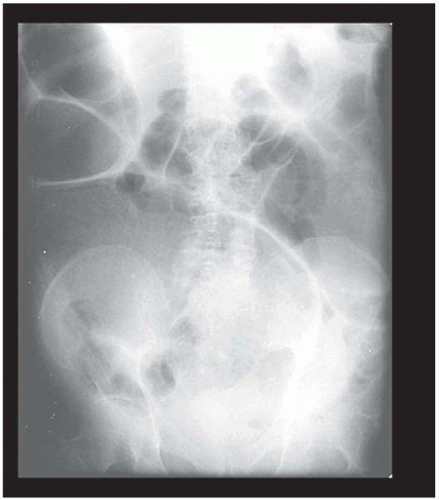

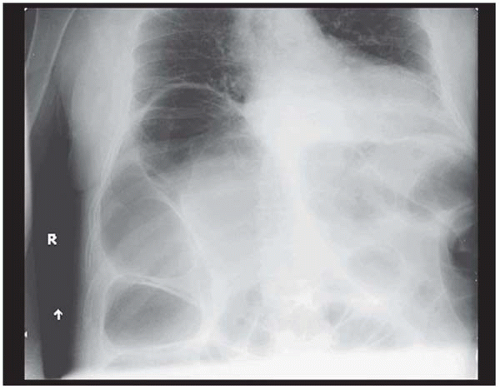

An abdominal radiograph is a simple and effective method of diagnosing large bowel obstruction. The proximal colon is often distended with air and a cutoff is seen at the level of the obstruction. The next step is to determine the degree, partial versus complete, and location of the obstruction using a water-contrast enema (with Hypaque or Gastrografin). Partial obstructions are amenable to endoscopic dilation (for strictures), endoscopic stenting (for strictures or carcinoma), and preoperative bowel preparations. Complete obstructions require early surgical intervention for proximal decompression. Location with respect to right colon, left colon, or rectum is important in planning any therapeutic intervention. In addition, length of the obstruction and presence of mucosal irregularities give clues to the etiology and candidacy for stenting.

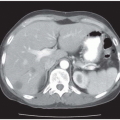

Following the water-soluble enema, a computed tomography (CT) scan is performed, which provides extraluminal information about the cause and nature of the obstruction and associated pathology, such as extrinsic compression, tumor size, presence of metastases, perforation, or signs of diverticulitis. However, if the patient requires an exploratory laparotomy, then a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is unnecessary because the time can be spent resuscitating. Any pathology present can be evaluated intraoperatively, and appropriate decisions can be made at that time.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree