Case 19

Presentation

A 60-year-old man presents to his physician with dyspepsia and mild anemia. He is referred to the endoscopic unit. Except for these vague symptoms, the patient is in good condition. The abdominal examination is normal.

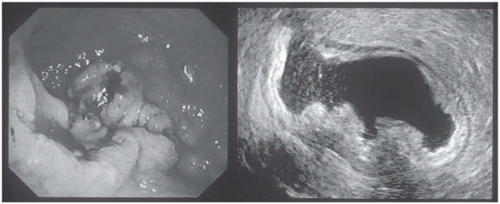

▪ Endoscopic and Endosonographic Images

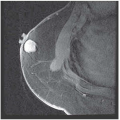

Endoscopy and Endosonography Report

The esophagus is normal, but in the body of the stomach (corpus region) there is a tumor with ulceration, with no signs of active bleeding. Endosonography demonstrates that the tumor encompasses the entire gastric wall and is considered as category T3 (Union Internationale Contre le Cancer [UICC]/American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC]).

Case Continued

Biopsies are obtained. Histologic study reveals adenocarcinoma of the stomach, intestinal type (Lauren classification).

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis for a gastric mass includes malignancies such as gastric adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, and gastrointestinal (GI) stromal tumors (GISTs). The initial diagnostic modality for gastric cancer is upper GI endoscopy. Following that, endoscopic ultrasound might be used to reveal the depth of tumor infiltration. Endosonography has the advantage of identifying early gastric cancer that can be treated by minimally invasive procedures.

Typically in the development of adenocarcinoma of the stomach, symptoms are minimal until relatively late in the course of the disease. A high index of suspicion must be maintained to avoid delay in diagnosis. Weight loss and abdominal pain are the most frequent initial symptoms. Weight loss often indicates more advanced disease, and patients with weight loss have a shorter survival than those without. Abdominal pain begins as insidious upper abdominal discomfort that ranges in intensity from a vague sense of postprandial fullness to a severe, steady pain. Anorexia and nausea are quite common. Dysphagia may indicate a cancer in the cardia or gastroesophageal junction. Vomiting is more consistent with an antral carcinoma obstructing the pylorus. Patients with scirrhous carcinomas (e.g., linitis

plastica) may develop early satiety. Although 20% of patients have melena, massive hemorrhage is more common with leiomyoma or GIST. Physical examination cannot detect an early carcinoma. An epigastric mass, enlarged liver, ascites, jaundice, or palpable supraclavicular lymph nodes indicate extensive and incurable disease.

plastica) may develop early satiety. Although 20% of patients have melena, massive hemorrhage is more common with leiomyoma or GIST. Physical examination cannot detect an early carcinoma. An epigastric mass, enlarged liver, ascites, jaundice, or palpable supraclavicular lymph nodes indicate extensive and incurable disease.

Identification of asymptomatic patients at high risk for developing gastric cancer is warranted. However, mass screening programs, as in Japan, are not cost-effective in Western countries.

GI lymphomas and especially mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue (MALT) lymphomas have to be ruled out prior to therapy; these patients are treated primarily by chemotherapy. Furthermore, if MALT lymphoma is present, Helicobacter pylori status has to be considered.

Discussion

Despite the diminishing prevalence, adenocarcinoma of the stomach still has significant clinical importance. Between 1980 and 2000, the incidence of gastric cancer declined by about 45% and the location of the tumor has changed. The tumors used to be primarily located in the distal part of the stomach, but now they are predominantly present in the subcardial region. Gastric cancer is extremely rare in patients younger than the age of 30; thereafter, it increases rapidly and steadily reaches the highest rates in the oldest age groups, both in males and females (median age: 68 for men and 74 for women).

Case Continued

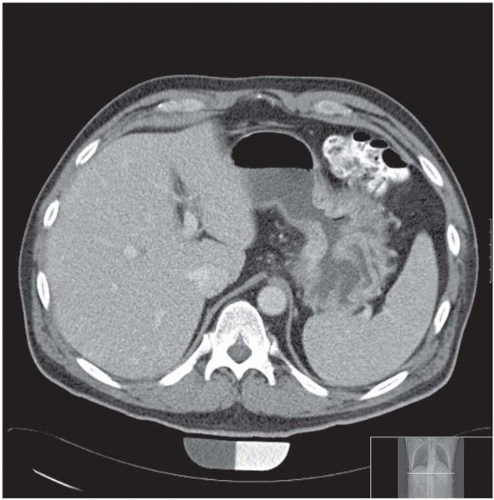

The patient is admitted to a specialized surgical unit for evaluation. The patient undergoes a staging computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen.

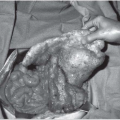

Diagnosis and Recommendation

Using endoscopy and CT scan, locally advanced adenocarcinoma in the body of the stomach is diagnosed. The patient is referred to surgery. Prior to proceeding with surgical exploration, distant metastases have to be excluded. On CT scan, secondary signs of peritoneal carcinomatosis such as ascites may be recognized. If there is any suspicion of peritoneal carcinomatosis, a diagnostic laparoscopy should be performed. If there is evidence of peritoneal spread, prognosis of the patient cannot be altered by surgery. In women, metastases to the ovaries (Krukenberg tumors) must be ruled out by CT scan.