Case 17

Presentation

A 59-year old man with no significant past medical history presents with symptoms of progressive dysphagia lasting 2 months. He can only tolerate a semisolid to liquid diet. The hold-up sensation resides at the thoracic inlet; he also regurgitates sometimes. He used to be a heavy smoker but has given up smoking for about 5 years. He drinks heavily, and has consumed a bottle of whiskey every week for many years. He has lost about 10 pounds in weight. Physical examination is unremarkable.

Differential Diagnosis

In an elderly man with symptoms of progressive dysphagia and weight loss, an obstructive malignant growth has to be considered. In areas where esophageal cancer is common, this should be high on the list of the differential diagnosis. Smoking and alcohol intake are both predisposing factors. Bronchogenic carcinoma with extrinsic compression of the esophagus by the primary tumor or mediastinal metastatic lymph nodes is also possible. The location of the complaint of dysphagia, however, does not necessarily equate to the level of the obstruction. The sensation of hold-up is usually above, but not below, the actual site of cancer.

Recommendation

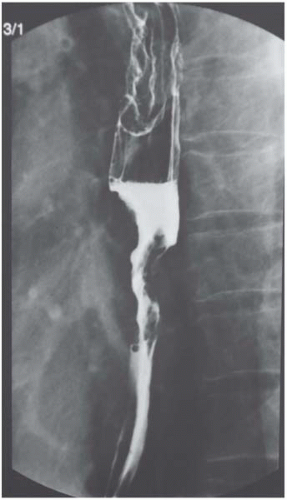

Barium contrast swallow and endoscopy.

Case Continued

The endoscopy reveals two ulcerative tumors, one measuring 26 to 30 cm from the incisor and the other 31 to -36 cm. The intervening mucosa seems normal. Staining with Lugol’s iodine does not reveal other lesions. Biopsies later confirm squamous cell cancers for both tumors. A bronchoscopy is also performed, which shows that both vocal cords are mobile, and there is no mucosal lesion seen in the tracheobronchial tree.

Diagnosis

Squamous cell esophageal cancer.

Discussion

In the West, adenocarcinoma of the lower esophagus and gastric cardia has surpassed squamous cell cancer as the predominant cell type, believed to be related to gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity, and Barrett’s esophagus, which are uncommon in Asian populations. When found, squamous cell cancers tend to locate in the midesophagus; they can be multicentric, and have the propensity for submucosal spread. Both are reasons prompting the use of special stains like Lugol’s iodine to look for unsuspected lesions in the rest of the esophagus. A panendoscopy is also a necessity to examine the tracheobronchial tree for involvement by the esophageal tumor. This is of particular importance for tumors that are located in the upper or midesophagus because of the close proximity to the airway. Tumor involvement of the tracheobronchial tree contraindicates resection. The rest of the upper aerodigestive tract is also screened for synchronous tumors because of the phenomenon of field cancerization.

Recommendations

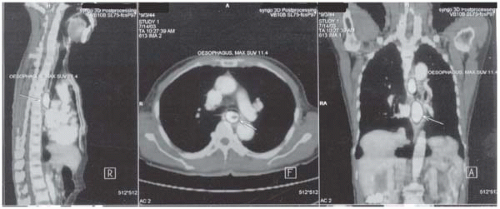

Further staging and diagnostic workup are undertaken. Positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) scan and endoscopic ultrasound are carried out.

Case Continued

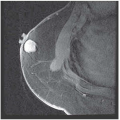

On endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), both tumors are found to involve the full thickness of the esophageal wall. Multiple small lymph nodes, up to 1.5 cm in size, are seen. The celiac lymph node is not enlarged. The staging on EUS is therefore T3 N1. Pulmonary function tests show no contraindication to proceed with major surgery.

Discussion

Accurate staging of esophageal cancer has gained more importance because of stage-directed therapy. The sensitivity and specificity of a conventional CT scan for local tumor infiltration and local-regional lymph node are suboptimal. PET with 18-F-fluoro-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) is increasingly used, and is of particular use in identifying distant nodal or systemic metastases. Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy rates for the detection of distant metastases of 88%, 93%, and 91%, respectively, have been reported, but local-regional staging of N1 disease seems much inferior to EUS. On EUS, lymph nodes that are typically identified as harboring metastatic disease usually are larger than 5 mm in size and oval in shape, with an echo-poor pattern and smooth borders. The accuracy of determining T stage ranges between 85% and 90%, while nodal staging accuracy approximates 70% to 90%. When EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (EUS-FNA) is used, the diagnostic accuracy extends beyond 90%.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree