Case 14

Presentation

A 67-year-old man who is a retired shipyard worker with a 30-year asbestos exposure is seen in the emergency department with a history of progressive shortness of breath and cough for 6 months. Prior to this 6-month history of progressive dyspnea, he was performance status 0, with a past medical history of hypertension, and he relates a loss of appetite as well as a cough over this period. Physical examination of this former 16-pack-year smoker reveals dullness to percussion and distant breath sounds on the right side. Fortunately, the hospital had an old chest radiograph taken after an automobile accident 1 year ago, for comparison. A complete blood cell (CBC) count reveals a platelet count of 450,000/mL.

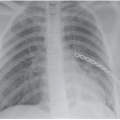

▪ Chest X-Rays

X-Ray Report

Compared with a previous film taken 1 year earlier (left), there has been the development of a large right-sided pleural effusion (above). The cardiac silhouette is similar to previous studies. The lung fields demonstrate scarring but no dominant masses.

Differential Diagnosis

The development of new pleural effusion in a person with asbestos exposure is a particularly ominous sign. The differential diagnosis must include mesothelioma, stage IIIB lung cancer (because the risk for development of lung cancer in asbestos-exposed former or present smokers is 40 times higher than in nonsmokers), postpneumonic effusion, pleural metastases from another primary tumor (specifically of gastrointestinal origin), and a traumatic hemithorax. In the absence of a history of injury and other constitutional symptoms, the primary differential must be between lung cancer and mesothelioma.

Discussion

Mesothelioma usually affects older men in their 50s, 60s, and 70s with a 25- to 40-year latency period between occupational asbestos exposure and the development of the tumor. The duration of symptoms will vary from 2 weeks to 2 years, with most series having a median time to diagnosis from symptoms of 2 to 3 months. The right side is affected more than the left side (60% vs 40%) most likely due to its greater volume.

Dyspnea will be present in 50% to 70% of the cases and, indeed, 80% of the patients will present with dyspnea and effusion. In 95% of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma, a pleural effusion will be documented at some time in the course of the disease.

Nonspecific laboratory findings seen in mesothelioma patients include hypergammaglobulinemia, eosinophilia, and/or anemia of chronic disease. The most striking laboratory abnormality is thrombocytosis (platelet count greater than 400,000), which is seen in 60% to 90% of patients, and approximately 15% of patients will have platelet counts greater than 1,000,000. At present, validated serum markers that are both sensitive and specific for mesothelioma do not exist.

A large, unexplained pleural effusion and minimal or moderate evidence of pleural thickening demands immediate workup, which includes thoracentesis and pleural biopsy or thoracoscopy. Multiple closed pleural biopsies can be performed to avoid sampling error with the Abrams or Cope needle, and this will be able to aid in the diagnosis in 30% to 50% of the cases.

Patients who develop a large effusion and who have negative studies on thoracentesis and pleural biopsy or who recur with effusion after initial thoracentesis should have a video-assisted thoracoscopy. Thoracoscopic examination allows for targeted biopsies, which can then be analyzed with the proper pathologic markers, as well as to determine whether the lung will expand. Thoracoscopy can estimate the amount of disease on the diaphragm, pericardium, chest wall, and nodes. A chest wall mass from seeding of the biopsy site or surgical scar is an uncommon complication (approximately 10%).

Open biopsy (using an incision that can be incorporated into the definitive incision if a major resection is entertained after diagnosis) is required if there is no free pleural space due to previous treatment of pleural effusion and the bulk of the disease in the hemithorax is solid.

Recommendation

Thoracentesis with pleural biopsy and computed tomography (CT) scan.

Case Continued

The thoracentesis revealed 1,000 mL of straw-colored fluid, but only atypical mesothelial cells were seen, and the cytological examination of the cell block using immunohistochemistries was not able to diagnose epithelial malignancy. The pleural biopsy revealed fibrous tissue compatible with a pleural plaque.

Recommendation

Video-assisted thoracoscopy with targeted pleural biopsies.

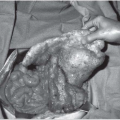

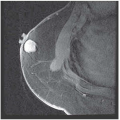

▪ Endoscopic Images

Endoscopy Report

Thoracoscopic examination reveals 3 L of strawcolored fluid and multiple nodular densities over the chest wall and diaphragm (upper image), as well as the lung and pericardium, along with asbestos plaques. A closer examination of the chest wall and intercostal bundles is provided in the lower image. Multiple biopsies were taken of the pleural nodules.

Diagnosis

Tubulopapillary neoplasm consistent with epithelial mesothelioma.

Discussion

With the diagnosis of mesothelioma now finalized, it is important to define the extent of disease, the patient’s performance status, and his suitability for a multimodality approach using surgery and chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. Before proceeding with these tests, a discussion with the patient must define his options. The patient is informed that the median survival of patients who select supportive care only for mesothelioma ranges widely from 4 to 13 months. Patients who elect for only chemotherapy will have a median survival of approximately 12 months even with the newest combination of pemetrexed and cisplatin, which has a 41% response rate. Patients who are eligible for multimodality approaches involving a cytoreduction of their disease by pleurectomy decortication or extrapleural pneumonectomy will have median survivals that approach 24 months, depending upon their postoperative pathologic staging status.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree