I. ANATOMY

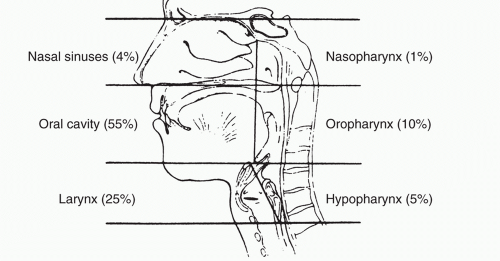

Understanding HNC begins with an understanding of aerodigestive anatomy. There are five sites within the head and neck region. These include the larynx, pharynx, oral cavity, paranasal sinuses, and the major salivary glands. Each site is composed of specific subsites (Table 5.1). A cross-sectional view of the anatomic regions and the relative frequency of cancer occurring in each area are shown in Figure 5.1. Identification of the primary site and extent of disease are critical for treatment planning, as will be discussed at length subsequently. Although thyroid cancers are frequently treated by otolaryngologists, they have unique pathologic and treatment issues and are covered in Chapter 13. Skin cancers, which are also common in the head and neck region, are discussed in Chapter 14.

II. EPIDEMIOLOGY

Approximately 40,000 cases of SCAs of the head and neck are diagnosed annually within the United States. Although SCAs of the head and neck are often considered together because of their anatomic proximity, it is important to recognize that HNC is comprised of a variety of distinct disease entities that may be distinguished based on etiology, histology, epidemiology, and natural history. These include the following: (1) SCA associated with traditional risk factors of smoking and drinking, (2) nasopharyngeal carcinomas (NPCs), and (3) human papillomavirus (HPV) associated oropharyngeal cancers. The distinction between these entities is critical in order to make appropriate treatment decisions.

TABLE 5.1 Upper Aerodigestive Tract Sites and Subsites

Region

Area

Site

Oral cavity

—

Lip

Oral tongue

Upper gum

Lower gum

Floor of mouth

Hard palate

Cheek mucosa

Vestibule of mouth

Retromolar area

Pharynx

Nasopharynx

Superior wall

Posterior wall

Lateral wall

Anterior wall

Oropharynx

Base of tongue

Soft palate

Uvula

Tonsil, tonsillar fossa, and pillar

Valleculae

Lateral wall of oropharynx

Hypopharynx

Piriform sinus

Postcricoid region

Hypopharyngeal aspect of aryepiglottic fold

Posterior wall of hypopharynx

Larynx

Supraglottis

Suprahyoid epiglottis

Infrahyoid epiglottis

Laryngeal aspect of aryepiglottic folds

Arytenoid

Ventricular band (false cords)

Glottis

True vocal cords

Anterior commissure

Posterior commissure

Subglottis

Subglottis

Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

Nasal cavity

Septum

Floor

Lateral wall

Vestibule

Maxillary sinus

Anteroinferior

Superoposterior

Ethmoid sinus

Frontal sinus

FIGURE 5.1 Anatomic divisions of the head and neck. Percentages indicate the relative frequencies of carcinoma in these regions.

A. SCA with traditional risk factors

Historically, HNCs have been associated with exposure to mucosal irritants such as tobacco and alcohol. Strong epidemiologic data demonstrates that there is a dose-response relationship between cigarette use and the incidence of HNC. Of note, alcohol use interacts synergistically with tobacco use, dramatically increasing the risk of cancer. Chewing tobacco is associated with oral cavity cancers. The median age at diagnosis for tobacco-associated HNC ranges from 55 to 67 years, depending on the site. There is a marked male predominance (3:1), which is felt to reflect the patterns of prior tobacco use within the general population. Of note, there has been a decreasing incidence of HNC associated with traditional risk factors.

B. NPC

NPCs have a highly variable rate of occurrence depending on geographic region. Areas with high rates of NPC include China, Southeast Asia, and North Africa. In low-risk areas, NPC is quite uncommon. Epidemiologic studies are ongoing to identify potential differences in the etiology and behavior of NPC in low- and high-risk regions. In low-risk areas, NPC has a bimodal age distribution with peak incidence occurring between the ages of 15 and 25 years, and again between the ages of 56 and 79 years. In high-risk areas, the initial peak is lacking, and incidence rates start to decline at an earlier age.

Risk factors for the development of NPC include infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), environmental factors, and genetic predisposition. In the low-risk areas, the early peak in incidence is thought to be due to genetic susceptibility in conjunction with exposure to EBV and/or other environmental contacts. EBV appears to be associated with NPC in high-risk areas; however, in the low-risk population, more traditional risk factors such as tobacco and alcohol use may play a role. Of note, the incidence of EBV infection far exceeds the rate of cancer development, thus research is ongoing to try and identify determinates that favor the development of overt cancer.

NPC is usually classified histologically using one of two systems. The first is a World Health Organization classification that breaks NPC into three subtypes: type 1, keratinizing SCA; type 2, nonkeratinizing, well differentiated SCA; and type 3, nonkeratinizing, undifferentiated SCA. Alternatively, cancers may be categorized as (1) well differentiated keratinizing SCA and (2) undifferentiated SCA. Keratinizing SCA, is most common in the low-risk and older patients, whereas undifferentiated SCA is more common in the high-risk areas.

C. HPV-associated oropharyngeal carcinomas

Over the past decade, there has been a marked increase in the incidence of oropharyngeal carcinomas, specifically tumors arising from tonsillar tissue. Data now indicates that a substantial percentage of these tumors are related to infections with HPV. The vast majority of cases within the United States are associated with serotype 16. In general, HPV-associated tonsillar cancers have a better prognosis. It should be noted, however, that a heavy smoking history mitigates the favorable outcome to a significant degree. Histologically, HPV-associated tumors are frequently described as poorly differentiated due to the immature appearance of the cells. This is a misconception as tumors cells are similar in appearance to the specialized epithelial lining of the tonsillar crypts. In addition, tumor cells are frequently basaloid in appearance. It is important to distinguish tonsillar cancers with a basaloid appearance from “basaloid SCAs,” which are an aggressive subtype thought to have a poor outcome.

III. PRESENTING SYMPTOMS

The presenting symptoms of HNC vary based on the primary site; thus, a careful history may help guide the diagnostic work-up. For example, patients with hoarseness may have cancers of the larynx and should undergo endoscopic evaluation for a laryngeal mass. Common presenting complaints include pain, nonhealing ulcerative lesions, dysphagia, odynophagia, hemoptysis, epistaxis, sinus congestion, globus sensation, headaches, nonhealing dental infections, and a nonpainful

neck mass. Presenting complaints of HNC are similar to symptoms associated with benign problems such as bacterial pharyngitis or sinusitis. This may lead to a protracted delay in diagnosis. Occasionally, patients may also present with complications secondary to local disease such as airway obstruction or aspiration pneumonia.

Although the bulk of patients present with symptoms related to local disease, it is important to assess systemic manifestations as well. Patients with more advanced disease may present with weight loss due to decreased oral intake and/or cancer cachexia. Other systemic manifestations of such as fatigue, neurocognitive changes, and debility should also be ascertained.

IV. STAGING AND WORK-UP

A. Initial work-up

Treatment is based on the extent of disease at presentation, so an accurate staging work-up is critical. A careful history may help point to the primary site and suggest involved structures. A thorough head and neck evaluation will include an assessment of the primary site and the extent of nodal disease. An endoscopic exam is usually performed on initial exam by an otolaryngologist to identify and/or confirm the primary site. Most patients with laryngeal or pharyngeal tumors will undergo direct laryngoscopy with biopsy to determine the extent of disease and to rule out a second primary tumor. Imaging studies are considered a standard component of the work-up in patients with locally advanced disease. The purpose of radiographic studies is to clearly define the extent of local disease, to identify nodal spread, and to rule out metastatic disease or a second primary tumor. Computed tomography scans, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography scans may each contribute unique clinical information; it is therefore important to discuss the appropriate radiographic evaluation with the radiologist in order to optimize the staging work-up and to provide clinicians with the information needed for treatment planning.

B. TNM classification

The American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system integrates clinical and pathologic information regarding size of the primary tumor (T-stage); the size, number, and location of regional lymph nodes (N-stage); and the presence of distant metastases (M-stage). Each disease site within the head and neck region has a T-staging system. However, all sites, with the exception of NPCs, share a common nodal staging system. Because NPCs are associated with extensive nodal disease, a specific N-staging system has been developed that is applicable only to this cohort of patients.

Based on the T, N, and M stages, patients are grouped into overall stages I through IV (Tables 5.2 and 5.3). In general, stage I and II

cancers are small and do not have evidence of nodal or distant spread. Stage III includes either larger primary tumors or tumors with early regional node involvement. Stage IV lesions may be either large tumors with significant local extension, extensive nodal disease, or distant metastatic disease. The stage grouping has been developed so that advancing stage is associated with worsening prognosis. With the recognition that patients with HPV-positive disease have an improved survival despite advanced disease, changes to the TNM classification may be anticipated.

TABLE 5.2 TNM Staging System for Carcinomas of the Oral Cavity

Primary Tumor

TX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

No evidence of primary tumor

Tis

Carcinoma in situ

T1

Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension

T2

Tumor >2 cm but not >4 cm

T3

Tumor >4 cm in greatest dimension

T4a

Tumor invades adjacent structures (e.g., through cortical bone) into deep extrinsic muscle of the tongue, maxillary sinus, and skin of face

T4b

Tumor invades masticator space, pterygoid plates, or skull base and/or encases internal carotid artery

Regional Nodal Status

NX

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0

No regional lymph node metastasis

N1

Metastasis in a single ipsilateral node ≤3 cm in greatest dimension

N2a

Metastasis in a single ipsilateral node >3 cm but not >6 cm in greatest dimension

N2b

Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral nodes not >6 cm in greatest dimension

N2c

Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes not >6 cm in greatest dimension

N3

Metastasis in a lymph node >6 cm in greatest dimension

Distant Metastasis

M0

No distant metastasis

M1

Distant metastasis

Adapted from Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CA(eds). AJCC cancer staging manual (7th ed.).

New York: Springer; 2010, p. 37 .

C. Assessment of comorbid disease and psychosocial issues

An initial evaluation is not complete without a detailed assessment of medical comorbidities, psychological issues, social supports, and financial status. Patients with SCA secondary to smoking and drinking frequently have comorbid diseases such as cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and alcohol-related disorders. Risk stratification systems specific to HNC patients have been developed to assess long-term prognosis

based on common comorbidities. Understanding the patient’s long-term prognosis may help guide treatment decisions. A substance abuse history should be obtained from all patients, and patients with active abuse issues should be referred for appropriate counseling. Patients who are actively smoking should be advised to quit and should be referred to appropriate support services to aid in this effort. Depression and suicide are common in HNC patients, thus initial and ongoing screening for mood disorders is appropriate. Patients with the traditional risk factors of smoking and drinking may have poor support systems and lower socioeconomic status. Defining these issues at the time of initial diagnosis is important because treatment may need to be adjusted based on the patient’s capacity to comply with therapy.

TABLE 5.3 Stage Grouping for Carcinomas of the Oral Cavity, Pharynx, Hypopharynx Larynx, and Paranasal Sinuses

Stage

Groups

0

Tis, N0, M0

I

T1, N0, M0

II

T2, N0, M0

III

T3, N0, M0

T1 or T2 or T3, N1, M0

IVa

T4a, N0 or N1, M0

T1-4a, N2, M0

IVb

T4b, any N, M0

Any T, N3, M0

IVc

Any T, any N, M1

Adapted from Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CA (eds). AJCC cancer staging manual (7th ed.).

New York: Springer; 2010.

In addition to general considerations in the work-up of HNC as noted above, there are also specific health-related issues that may impact on the decision to use specific chemotherapy agents. Specific issues are delineated below.

1. Bone marrow function. Chronic alcoholism, malnutrition, and tumor-related weight loss contribute to a significant incidence of folate deficiency and decreased bone marrow reserve in many patients.

2. Pulmonary function. Current or distant heavy smoking increases the likelihood of COPD and chronic bronchitis, leading to an increased risk of pulmonary infection during treatment. In addition to impaired pulmonary reserve, patients have a propensity to aspirate secondary to swallowing abnormalities and may have difficulty handling their secretions.

3. Renal function. Platinum compounds are used as first-line agents in HNC therapy. Adequate baseline renal function and continued monitoring of renal function is needed for administration. Methotrexate is renally excreted and may accumulate in patients with renal insufficiency, leading to increased toxicity.

4. Hepatic function. The presence of cirrhosis, whether related to alcoholism or viral hepatitis, can complicate management as it can impair the ability to accomplish forced hydration by leading to third space accumulations of ascites or edema. Routine use of diuretics may exacerbate treatment-related electrolyte abnormalities.

5. Neuropathy. Platinum compounds and taxanes may cause peripheral or autonomic neuropathy. Hearing loss may develop secondary to chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Patients should be screened for baseline neuropathy or hearing loss and have their therapies adjusted accordingly. Comorbidities that may be associated with baseline neuropathy include alcoholism and diabetes.

6. Fertility. All chemotherapy agents may impair fertility either temporarily or permanently. For male patients who wish to ensure their reproductive capacity, sperm donation should be accomplished promptly. For female patients, induced ovulation and harvesting and preservation of ova may be considered.

7. Concomitant drugs. Antihypertensives, diuretics, and drugs used for glycemic control all need careful assessment, monitoring, and adjustment during therapy as patients undergo treatment. Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and limited oral intake often lead to dehydration and weight loss, making hypotension a common occurrence during therapy. Patients may need to be weaned off antihypertensives. The use of glucocorticoids as an adjunct to antiemetics and to prevent anaphylactic reactions, coupled with irregular feeding patterns, make glycemic control difficult. It is best to emphasize careful monitoring to avoid hypoglycemia rather than focus on hyperglycemia, which is not metabolically (homeostatically) significant.

V. NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of SCA of the head and neck can be quite variable. Tumor growth rates range from slow progression over years to rapidly expanding masses that progress measurably over days to weeks. There is a correlation between histologic grade and the rate of tumor growth, though this association is weak. The rapidity of growth may play a role in treatment decisions as surgeons may be reluctant to operate on large, rapidly expanding tumors.

Early stage cancers (stage I and II) are associated with a high cure rate. Unfortunately, the majority of patients present with locally advanced disease (T3, T4, or nodal disease). Of note, prominent nodal disease is common in patients with both NPC and HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Metastatic disease at presentation is infrequent in all types of HNC, but it may develop following initial therapy. The most powerful predictor for development of metastatic disease

is the extent of nodal disease at presentation. Patients who present with N0-N1 disease have a less than 5% chance of developing distant metastases, whereas patients with N2 or greater nodal disease have a 25% to 30% chance of subsequent distant spread. The most common sites of metastatic disease are lung, liver, and bone. Brain metastases are rare for patients with SCA of the head and neck.

Most recurrences appear within 18 months of primary treatment, and 90% appear within 2 years. Patients who are not cured usually die from the cancer within 3 to 4 years of diagnosis. Patients who succumb to the cancer generally experience local, regional, and distant failure in equal proportions. The manifestations of end-stage disease are typified by inanition, cachexia, aspiration, respiratory difficulty due to trouble with secretions or obstruction, fistulas, oral or neck ulceration, edema of the mucosal structures or face, and pain. Among survivors, the risk of second primary head and neck, lung, and esophagus tumors is a significant problem, thus long-term surveillance is indicated.

VI. TREATMENT: GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Treatment of HNC, regardless of histologic cell type or causal factors, requires a multidisciplinary approach with a team of experienced clinicians including head and neck surgeons, radiation and medical oncologists, nutritionists, speech and language pathologist, and oral health providers. Working with the patient, the treatment team must come to a consensus regarding (1) the goals of therapy, (2) treatment options that will adequately meet those goals, and (3) optimal methods for implementation and monitoring of treatment and treatment-related side effects. Although treatment paradigms are evolving rapidly, therapeutic principles for each of the major clinical entities are reviewed below.

A. SCA with traditional risk factors of tobacco and alcohol use

1. Early-stage disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Carcinomas of the Head and Neck

Carcinomas of the Head and Neck

Barbara A. Murphy

Head and neck cancers (HNCs) are defined as those arising from the upper aerodigestive system. Although a variety of histopathologic subtypes have been associated with the anatomic region, the vast majority are squamous cell carcinoma (SCA); thus, the following chapter will focus specifically on this subtype.