I. CARCINOMA OF THE ESOPHAGUS

A. General considerations and aims of therapy

1. Epidemiology. Cancer of the esophagus is more common in men than women and occurs more often in black patients than in white patients. The average patient is in his or her 60s at presentation. Esophageal cancers are either adenocarcinoma (EAC) or squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Smoking and regular alcohol use are strong risk factors for ESCC and only moderate risk factors for EAC; the risk is reduced with smoking cessation in ESCC but not EAC. A unique risk factor for ESCC is other aerodigestive tract malignancies, such as head and neck or lung cancer. Risk factors associated with EAC only appear to be gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and Barrett esophagitis.

EAC tends to involve the lower third of that organ, whereas the middle third is the most common site for ESCC. Although ESCC remains the most common in Asian countries, especially East Asia, the incidence of EAC has been increasing over the past two decades in Western countries. In the United States over this time, the incidence of EAC has increased three- to eightfold. The ratio of ESCC:EAC during this time has changed from 4.7:1 in 1975 to 0.43:1 in 1998. This is believed primarily to be due to increased GERD from rising rates of obesity in these regions of the world.

Optimal chemotherapy for the two histologic types of esophageal cancer is not known to be different in terms of overall survival (OS). There does appear to be an improved rate of response to neoadjuvant therapy with ESCC, but EAC patients who experience a response have an improved long-term prognosis compared to their ESCC counterparts, likely explaining the lack of OS difference.

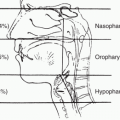

2. Clinical manifestations and pretreatment evaluation. Carcinoma of the esophagus is usually associated with progressive and persistent dysphagia. Pain, hoarseness, weight loss, and chronic cough are unfavorable manifestations that indicate spread to regional structures (e.g., mediastinal nodes), recurrent laryngeal nerves, or fistula formation between the esophagus and the airway. The most common sites of metastasis are regional lymph nodes (which may include cervical, supraclavicular, intrathoracic, diaphragmatic, celiac axis, or periaortic lymph nodes), the liver, and the lungs.

Diagnosis is usually made by barium swallow, endoscopy, and biopsy or lavage cytology. Staging should be based on computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and chest, careful physical examination of the cervical and supraclavicular nodes, and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT imaging to rule

out distant metastatic disease. In patients without metastatic disease, endoscopic esophageal ultrasound (EUS) may be useful in assessing the depth of tumor invasion, given the difference in management of T1-T2 lesions versus T3-T4 lesions. The preoperative staging of esophageal cancer with EUS is still inadequate, owing to the inability to evaluate lymph nodes accurately; PET/CT does not seem to improve this detection for locoregional nodal status. Laparoscopy has the advantage of changing management in approximately 20% of patients who have otherwise been fully staged with CT, PET/CT, and EUS. Bronchoscopy should be done for upper- and middle-third tumors to rule out a bronchoesophageal fistula. A bone scan is useful in patients with bone pain or tenderness. Survival is related to pathologic stage, which only can be defined surgically (Table 7.1).

3. Treatment and prognosis. The primary treatment of stage I and II carcinoma of the esophagus is surgical resection. About half of esophageal cancers are operable, and half of these are resectable. Complete surgical resection results in a median survival of approximately 18 months with 15% to 20% of patients surviving 5 years. Patients with more advanced disease (stage III) are best treated, at least initially, with nonsurgical means, usually a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy. In patients who respond to such treatment, the carcinoma may subsequently be operable, whereas patients with metastatic disease are best treated with systemic therapy. Palliative feeding procedures such as with a jejunostomy or gastrostomy tube may be useful if subsequent surgical resection is not to be done. For metastatic disease, the overall median survival time is less than 1 year, and the overall 5-year survival rate is 5% to 10%. The prognosis is related to the size of the lesion, the depth of penetration of the esophagus, and nodal involvement. Current controlled clinical trials are helping to evaluate the optimal chemotherapy regimen and combination with radiation in the neoadjuvant setting.

B. Combined-modality treatment for potentially curable patients

The poor results with immediate surgery, due in part to inadequate staging techniques, have focused attention for some years on preoperative combined-modality treatment with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or both, followed by surgery (or, in some instances, not followed by surgery). This approach is controversial because of uncertainty of staging and conflicting results from randomized clinical trials. When this approach is used, aggressive staging including EUS, CT scanning, and laparoscopy is needed and is often combined with jejunostomy feeding tube placement for nutritional support. Despite conflicting results from randomized trials, patients with stage II and III disease are often treated in this fashion.

TABLE 7.1 TNM Stages for Carcinoma of the Esophagus

Primary Tumor

Tis

HGD

T1

Invades lamina propria or submucosa

T1a

Invades lamina propria or muscularis mucosa

T1b

Invades submucosa

T2

Invades muscularis propria

T3

Invades adventitia

T4

Invades adjacent structures

T4a

Resectable tumor invading pleura, pericardium, or diaphragm

T4b

Unresectable tumor invading other adjacent structures such as aorta, vertebral body, trachea, etc.

Regional Lymph Nodes

N0

No regional nodal metastasis

N1

Metastasis in one to two regional nodes

N2

Metastasis in three to six regional nodes

N3

Metastasis in seven or more regional nodes

Distant Metastasis

M0

None

M1

Present

Stage Grouping for Squamous Cell Carcinoma* using TNM, grade (G), and tumor location†

0

Tis(HGD), N0, M0, G1/X, any location

IA

T1, N0, M0, G1/X, any location

IB

T1, N0, M0, G2-3, any location

T2-3, N0, M0, G1/X, lower/X

IIA

T2-3, N0, M0, G1/X, upper/middle

T2-3, N0, M0, G2-3, lower/X

IIB

T2-3, N0, M0, G2-3, upper/middle

T1-2, N1, M0, any G, any location

IIIA

T1-2, N2, M0, any G, any location

T3, N1, M0, any G, any location

T4a, N0, M0, any G, any location

IIIB

T3, N2, M0, any G, any location

IIIC

T4a, N1-2, M0, any G, any location

T4b, any N, M0, any G, any location

Any, N3, M0, any G, any location

IV

Any T, any N, M1, any G

Stage Grouping for Adenocarcinoma using TNM and G

0

Tis(HGD), N0, M0, G1/X

IA

T1, N0, M0, G1-2/X

IB

T1, N0, M0, G3

T2, N0, M0, G1-2/X

IIA

T2, N0, M0, G3

IIB

T3, N0, M0, any G

T1-2, N1, M0, any G

IIIA

T1-2, N2, M0, any G

T3, N1, M0, any G

T4a, N0, M0, any G

IIIB

T3, N2, M0, any G

IIIC

T4a, N1-2, M0, any G

T4b, Any N, M0, any G

Any T, N3, M0, any G

IV

Any T, Any N, M1, any G

HGD, high-grade dysplasia.

* Or mixed histology including a squamous component or not otherwise specified.

† Location of the primary cancer site defined by position of the upper (proximal) edge of the tumor in the esophagus. Upper = 10 to <25 cm, middle = 25 to <30 cm, and lower = 30 to 45 cm, esophagogastric junction/cardia = 5 cm below esophagogastric junction.

Modified from American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual (7th ed.). New York: Springer; 2010.

1. Preoperative chemotherapy. The National Cancer Institute Gastrointestinal Intergroup has reported a randomized trial of 440 patients with either EAC or ESCC that compared preoperative chemotherapy (cisplatin and fluorouracil [CF] for three cycles) versus surgery alone. After a median follow-up of 55.4 months, there were no median, 1-year, or 2-year survival differences between the two groups. These results differ compared with data from the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit in the United Kingdom, which included 802 patients randomized to receive either two cycles of preoperative CF followed by surgery versus surgery alone. Approximately 66% of patients had adenocarcinoma. Long-term follow-up at 6 years revealed a significant difference in 5-year OS (chemotherapy versus surgery alone, 23% versus 17.1%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-0.98; p = 0.03) regardless of histological subtype. Different proportions of the two different histologies contribute to the difficulties in interpretation of these trials.

2. Radiation therapy with surgery, chemotherapy, or both. Radiation therapy, as either a preoperative or a postoperative adjunct to surgery, has not improved OS in most series, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 0% to 10%. Combined-modality treatment of radiotherapy with chemotherapy has been superior. In addition, concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy is superior to sequentially-administered treatment. In a randomized trial, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 85-01, comparing radiotherapy alone with radiotherapy plus chemotherapy

in 121 patients, 88% of whom had squamous cell cancer, the RTOG reported a 5-year survival rate of 27% for the combined-modality group and 0% for the radiation therapy alone group, with median survival times of 14.1 months and 9.3 months, respectively. Most patients had stage T2 disease and were node negative by CT scanning.

a. Radiation therapy plus CF

(1) Radiation therapy 180 to 200 cGy/day for 3 weeks, 5 days weekly, then 2 additional weeks to the boost field for a total of 5040 cGy, and

(2) Fluorouracil 1000 mg/m2/day by continuous infusion for 4 days on weeks 1, 5, 8, and 11, with cisplatin 75 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) at 1 mg/min on the first day of each course. Reduce fluorouracil for severe diarrhea or stomatitis and cisplatin for severe neutropenia or thrombocytopenia.

More recent phase II trials are exploring radiation with alternative chemotherapy combinations, including cisplatin with a taxane as well as the addition of a targeted agent, namely epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antagonists.

Surgery, when it can be done, is probably appropriate because most patients treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy still have residual tumor. Even though a high proportion of patients, 25% in many series, have complete pathologic responses at surgery, the preoperative identification of these patients is not accurate. A large meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgery to surgery alone included nine randomized trials with 1116 patients. The meta-analysis demonstrated that neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgery improved the 3-year survival (p = 0.016) and reduced distant and local regional cancer recurrence (p = 0.038). There was also a higher rate of complete resection, although there was a nonsignificant trend toward increased treatment mortality with neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy is therefore a reasonable approach for patients who refuse surgery or whose disease is unresectable for anatomic or physiologic reasons, particularly those with ESCC.

C. Treatment of advanced (metastatic) disease

Various agents with modest activity when used alone are available. These include cisplatin, carboplatin, fluorouracil, bleomycin, paclitaxel, docetaxel, irinotecan, gemcitabine, methotrexate, mitomycin, vinorelbine, and doxorubicin. Response rates range from 15% to 30% and are usually brief. Most data are for ESCC, the exception being paclitaxel, which appears equally effective in

both histologic types. The most active drugs appear to be cisplatin, paclitaxel, and fluorouracil. Patients with no history of prior chemotherapy are more likely to respond than those who have had previous treatment. Single agents are less helpful than combination chemotherapy because of their lower response rates and brief duration of response. Cisplatin-based regimens have been most extensively tested. Among the most active are the following (for adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and gastroesophageal junction, see Section II).

1. CF

a. Cisplatin 75 to 100 mg/m2 IV on day 1.

b. Fluorouracil 1000 mg/m2/day as a continuous IV infusion on days 1 to 5. Repeat every 28 days.

2. Paclitaxel plus cisplatin

a. Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 IV on day 1.

b. Cisplatin 75 mg/m2 IV on day 1. Repeat every 21 days.

3. Carboplatin plus paclitaxel

a. Carboplatin area under the curve 5 IV on day 1.

b. Paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 IV on day 1. Repeat every 21 days.

4. Paclitaxel plus cisplatin plus fluorouracil

a. Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 IV over 3 hours on day 1.

b. Cisplatin 20 mg/m2/day IV on days 1 to 5.

c. Fluorouracil 750 mg/m2/day continuous IV on days 1 to 5. Repeat every 28 days.

5. Cisplatin plus irinotecan

a. Irinotecan 65 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 8, 15, and 22.

b. Cisplatin 30 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 8, 15, and 22. The regimen is repeated every 6 weeks.

6. Irinotecan plus fluorouracil plus leucovorin

a. Irinotecan 180 mg/m2 IV over 30 minutes followed by a 30-minute break.

b. Leucovorin 125 mg/m2 IV over 15 minutes.

c. Fluorouracil 400 mg/m2 IV over 3 to 4 minutes.

d. Fluorouracil 1200 mg/m2/day continuous IV for 2 days. The regimen is repeated every 2 weeks.

7. Cetuximab. The addition of cetuximab to a chemotherapy backbone has yet to demonstrate a significant progression-free survival or OS advantage, but does appear to improve response rates. A large clinical trial (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] 1206/Cancer and Leukemia Group B 80403) recently completed accrual and should further clarify the benefit of cetuximab in this disease.

8. Second-line therapy may be chosen from the list of alternative combination therapies or the single agents, including methotrexate 40 mg/m2 IV weekly; bleomycin 15 U/m2 IV twice weekly; vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 IV weekly; or mitomycin 20 mg/m2 IV

every 4 to 6 weeks. However, these therapies are not currently included in disease treatment guidelines, such as those of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).

D. Supportive care

Esophagitis during a combined-modality treatment program is nearly universal, and nutritional support frequently is required, preferably using alimentation by feeding tube placed by enterostomy. Peripheral alimentation is difficult with the continuous chemotherapy administration. Gastrostomy tubes are to be avoided in patients with potentially resectable lesions because of the usual requirement for a gastric pull-up after resection of the esophageal tumor.

E. Follow-up studies

For asymptomatic patients who have had potentially curative therapy, history and physical examination may be done every 3 to 6 months for years 1 to 3, every 6 months for years 3 to 5, and then annually. CT scans, endoscopy, chemistries, and complete blood count should be evaluated as clinically indicated.

II. GASTRIC CARCINOMA

A. General considerations and aims of therapy

1. Epidemiology. The incidence of stomach cancer has decreased dramatically in the United States since the beginning of the century, although it has stabilized in the last 20 years. The leading cause of cancer death in 1930, it now ranks 12th; however, worldwide it is the 4th most lethal cancer. No improvement has been seen over the last two decades though, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 45% to 71% in node-negative disease to 5% to 30% in node-positive or metastatic disease. The male-to-female ratio is nearly two to one. Stomach cancer is still the leading cause of cancer deaths among men in Japan and is also common in China, Finland, Poland, Peru, and Chile. A high rate of chronic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia of the stomach is associated with a high incidence of gastric cancer. Helicobacter pylori has been implicated in such changes and in gastric cancer, particularly the more distal “intestinal” type, as well as in peptic ulcer disease. Although the incidence in the United States has decreased, the location of gastric cancers has migrated proximally. Nearly half the stomach cancers occurring in white men are located proximally (gastroesophageal junction, cardia, and proximal lesser curvature).

2. Clinical manifestations and evaluation. The most common symptoms are weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, changes in bowel habits, fatigue, anorexia, and dysphagia. The diagnosis generally is made by endoscopy and biopsy, although barium swallow is frequently helpful. Endoscopic ultrasonography is

increasingly used; it is more accurate in gauging the depth of the cancer in the gastric wall than in determining nodal involvement. Laparoscopy is also helpful in improving clinical staging as it can more accurately identify peritoneal metastases and further evaluate the liver. Metastases are to the liver, pancreas, omentum, esophagus, and bile ducts by direct extension and to regional and distant lymph nodes such as those in the left supraclavicular area. Pulmonary and bone metastases are a late finding. Staging of suspected gastric cancer should initially include CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen (CA) 19-9, and CA 72-4 may be useful for subsequent assessment of the response to therapy. Prognosis is reflected by accurate staging (Table 7.2). The revised staging method classifies patients according to the number of pathologically involved regional lymph nodes. The groupings are one to two (N1), three to six (N2), and seven or more involved lymph nodes (N3).

3. Treatment and prognosis. Most stomach cancers are adenocarcinomas. Important prognostic factors include tumor grade and gross appearance. Diffusely infiltrating lesions are less likely to be cured than sharply circumscribed, nonulcerating lesions. The presence of regional lymph node involvement or involvement of contiguous organs in the surgical specimen indicates an increased likelihood of recurrence, as does the presence of dysphagia at the time of diagnosis. Patients with proximal lesions or lesions requiring total, rather than distal subtotal, gastrectomy are also at greater risk.

There has been controversy as to the contribution of extensive lymphadenectomy (D1 versus D2 dissection) to survival benefit. Japanese surgeons have widely promoted the D2 dissection; however, randomized clinical trials including the Dutch Gastric Cancer Group and the Medical Research Council trials did not show a survival benefit of D2 over D1 lymphadenectomy. However, there was increased morbidity and mortality for those patients who underwent the D2 dissection.

B. Treatment of advanced (metastatic, locally unresectable, or recurrent) disease

1. Single agents with activity include epirubicin, mitomycin, doxorubicin, cisplatin, etoposide, fluorouracil, irinotecan, hydroxyurea, the taxanes, and the nitrosoureas. Single agents have low response rates (15%-30%), brief durations of response, and few complete responses, and they have little impact on survival.

2. Combinations of drugs are more widely used than single agents, largely because of higher response rates, more frequent complete responses, and the potential of longer survival. A large randomized phase III study (V325) enrolling mostly patients with metastatic gastric cancer found improved response rate (36% versus 26%), delayed time to progression (5.6 months versus 3.7 months), improved OS (18.4% versus 8.8% at 2 years), delayed decline in functionality, and delayed deterioration of quality of life with docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil (DCF) compared to CF. Significant differences in grade 3 to 4 toxicities of DCF including diarrhea (19% versus 8%), neutropenia (82% versus 57%), neutropenic fever (29% versus 12%), and neurosensory (8% versus 3%) as compared to CF have limited its use as a standard regimen. DCF as a treatment for advanced disease, therefore, represents an important proof of principle; however, the toxicity is of significant concern.

TABLE 7.2 TNM Stages for Carcinoma of the Stomach

Primary Tumor

Tis

Carcinoma in situ

T1

Invades lamina propria, muscularis mucosa, or submucosa

T1a

Invades lamina propria or muscularis mucosa

T1b

Invades submucosa

T2

Invades muscularis propria

T3

Penetrates subserosal connective tissue without invasion of visceral peritoneum or adjacent structures*

T4

Invades serosa (visceral peritoneum) or adjacent structures*

T4a

Invades serosa (visceral peritoneum)

T4b

Invades adjacent structures*

Regional Lymph Nodes

N0

No regional nodal metastasis

N1

Metastasis in one to two regional lymph nodes

N2

Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes

N3

Metastasis in seven or more regional lymph nodes

Distant Metastasis

M0

None

M1

Present

Stage Grouping

0

Tis, N0, M0

IA

T1, N0, M0

IB

T1, N1, M0

T2, N0, M0

IIA

T1, N2, M0

T2, N1, M0

T3, N0, M0

IIB

T1, N3, M0

T2, N2, M0

T3, N1, M0

T4a, N0, M0

IIIA

T2, N3, M0

T3, N2, M0

T4a, N1, M0

IIIB

T3, N3, M0

T4a, N2, M0

T4b, N0-1, M0

IIIC

T4a, N3, M0

T4b, N2-3, M0

IV

Any T, any N, M1

* Adjacent structures: spleen, transverse colon, liver, diaphragm, pancreas, abdominal wall, adrenal gland, kidney, small intestine, retroperitoneum.

Modified from American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual (7th ed.). New York: Springer; 2010.

a. DCF. Dexamethasone 8 mg by mouth twice a day 1 day prior to chemotherapy, on the day of treatment, and the day after.

(1) Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 as a 1-hour infusion IV.

(2) Cisplatin 75 mg/m2 as a 2-hour infusion IV.

(3) Fluorouracil 750 mg/m2 daily as a continuous infusion IV on days 1 to 5. The regimen is repeated every 21 days.

b. CF

(1) Cisplatin 100 mg/m2 IV over 2 hours on day 1.

(2) Fluorouracil 1000 mg/m2 daily as a continuous infusion IV on days 1 to 5. The regimen is repeated every 21 days.

A UK study randomized 274 patients to receive either epirubicin, cisplatin, and protracted infusional fluorouracil (ECF) or fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and methotrexate, which was the standard at the time. The results favored ECF with improved response rate (45% versus 20%), a 2-month improvement in median survival, and an improved 2-year OS (14% versus 5%).

c. ECF

(1) Epirubicin 50 mg/m2 IV bolus on day 1 followed by CF.

(2) Cisplatin 60 mg/m2 IV over 2 hours on day 1.

(3) Fluorouracil 200 mg/m2 daily as a continuous infusion IV on days 1 to 21. The regimen is repeated every 21 days.

The REAL 2 study enrolled 1,002 patients with mostly metastatic gastric and gastroesophageal cancer and randomized patients in a two-by-two design to receive one of four anthracycline containing regimens: epirubicin and fluorouracil with either cisplatin (ECF) or oxaliplatin (EOF) as well as epirubicin and capecitabine with either cisplatin (ECX) or oxaliplatin (EOX). They concluded that capecitabine was noninferior to fluorouracil and that oxaliplatin was noninferior to cisplatin. Of note, oxaliplatin-containing regimens appeared to be better tolerated then cisplatin-containing regimens. In a secondary subset analysis, there was suggestion of a survival benefit of EOX compared with ECF.

d. EOF

(1) Epirubicin 50 mg/m2 IV bolus on day 1 followed by oxaliplatin and fluorouracil.

(2) Oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 IV over 2 hours on day 1.

(3) Fluorouracil 200 mg/m2 daily as a continuous infusion IV on days 1 to 21. The regimen is repeated every 21 days.

e. EOX

(1) Epirubicin 50 mg/m2 IV bolus on day 1 followed by oxaliplatin and capecitabine.

(2) Oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Carcinomas of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Carcinomas of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Maxwell Vergo

AI B. Benson III

Cancers of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, and anus) account for nearly 14% of all cases of cancer in the United States and for about 20% of cancer deaths. Colon cancer is by far the most common of these malignancies, with cancer of the rectum, stomach, esophagus, small intestine, and anus occurring with decreasing frequency. Surgery continues to be the principal curative modality, but radiation and chemotherapy have increasingly important roles and, in certain adjuvant situations, improve the cure rate produced by surgery. Select patients with isolated, resectable metastatic colorectal cancer lesions also may be cured with surgical resection. Chemotherapy alone is not curative in patients with overt metastatic disease. Recent combination drug regimens have produced objective responses in up to 60% of patients, with increasing numbers of individuals obtaining stabilization of their disease. There is little question that meaningful palliation and an increase in survival can be achieved in patients who respond to chemotherapy or achieve disease stabilization. Controlled clinical trials, often by cooperative groups, have been useful in defining the natural history and therapeutic benefit of various treatment modalities. Participation in such clinical trials is encouraged.