Fig. 26.1

Octreoscan (left) with a soft tissue mass in the distal ileum demonstrating increased radiotracer uptake, likely representing the primary carcinoid. There are also two hepatic lesions (arrows) in the inferior aspect of the right hepatic lobe concerning for multifocal metastatic disease (with corresponding CT scan showing the two liver metastases) (Courtesy of Dr. Tobias Else, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI)

Biochemical analysis includes plasma chromogranin A and urine 5-HIAA levels. Elevated chromogranin A levels are currently the most important blood marker for the disease, and a level greater than 5,000 μg/l correlates with a poor outcome [28, 29]. Chromogranin A levels, however, may also be elevated in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [30]. Collection of 24 h urine 5-HIAA levels is a useful marker for carcinoid tumors with a specificity of 88 % [31]. Patients should avoid eating nuts, bananas, plantains, pineapple, plums, kiwis, or tomatoes prior to collection as these foods may significantly increase urine 5-HIAA levels.

There is a lack of consensus for a unified staging system. Consequently, a number of different systems from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), World Health Organization (WHO), and European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) exist to stage NETs. In many cases, GI carcinoids are often staged using similar system with minor variations that is used for other cancers of the same organ. For example, stomach carcinoids are similarly staged as stomach adenocarcinoma with some variations such as the inclusion of tumor size for stomach carcinoids (Table 26.1).

Table 26.1

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging for gastric carcinoid (7th edition)

Primary tumor (T) | |

|---|---|

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis | Carcinoma in situ/dysplasia (tumor size less than 0.5 mm), confined to mucosa |

T1 | Tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa and 1 cm or less in size |

T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria or more than 1 cm in size |

T3 | Tumor penetrates subserosa |

T4 | Tumor invades visceral peritoneum (serosal) or other organs or adjacent structures (Fig. 17.9) |

For any T, add (m) for multiple tumors | |

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

|---|---|

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis (Fig. 17.10) |

Distant metastases (M) | |

|---|---|

M0 | No distant metastases |

M1 | Distant metastasis |

Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIA | T2 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIB | T3 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIA | T4 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIB | Any T | N1 | M0 |

Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Regardless, a number of these staging systems do take into account prognostic information such as tumor size, location of tumor origin, extent of invasion into organ of origin, evidence of regional/distant disease, and tumor grade (mitotic rate and/or Ki67 proliferation index).

The current AJCC proposed staging system for appendiceal carcinoid tumors has yet to be validated prospectively with survival statistics. T1 tumors are ≤2 cm in diameter; T2 tumors are between 2 and 4 cm, or involving the cecum; T3 tumors are >4 cm or extending into the ileum; and T4 tumors directly invade other structures. Stage I disease consists of T1 tumors, Stage II disease includes T2 and T3 tumors, Stage III disease includes T4 tumors or positive regional lymph nodes, and Stage IV disease involves distant metastatic disease [32] (Table 26.2). Most cases of appendiceal carcinoid present as localized disease (60 % of cases). However, regional spread (28 %) and metastatic disease (12 %) can be present at the time of diagnosis [33].

Table 26.2

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging for appendiceal carcinoid (7th edition)

Primary tumor (T) | |

|---|---|

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

T1 | Tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension |

T1a | Tumor 1 cm or less in greatest dimension |

T1b | Tumor more than 1 cm but not more than 2 cm |

T2 | Tumor more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm or with extension to the cecum |

T3 | Tumor more than 4 cm or with extension to the ileum |

T4 | Tumor directly invades other adjacent organs or structures, e.g., abdominal wall and skeletal muscle* |

Note: Tumor that is adherent to other organs or structures, grossly, is classified cT4. However, if no tumor is present in the adhesion, microscopically, the classification should be classified pT1-3 depending on the anatomical depth of wall invasion | |

*Penetration of the mesoapppendix does not seem to be as important a prognostic factor as the size of the primary tumor and is not separately categorized | |

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

|---|---|

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

Distant metastasis (M) | |

|---|---|

M0 | No distant metastasis |

M1 | Distant metastasis |

pTNM Pathologic Classification. The pT, pN, and pM categories correspond to the T, N, and M categories except that pM0 does not exist as a category | |

pN0. Histological examination of a regional lymphadenectomy specimen will ordinarily include 12 or more lymph nodes. If the lymph nodes are negative, but the number ordinarily examined is not met, classify as pN0 | |

Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

Stage II | T2, T3 | N0 | M0 |

Stage III | T4 | N0 | M0 |

Any T | N1 | M0 | |

Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

The ENETS/UICC staging for small bowel such as jejunoileal primaries is similar to colorectal cancer with T1 tumors confined to the submucosa and ≤1 cm, T2 tumors invade the submucosa or >1 cm, T3 tumors invade the subserosa, and T4 tumors invade adjacent structures. Stage I, IIA, IIb, and IIIA correspond to T1–T4 tumors, respectively. Stage IIIb represents metastatic disease to regional lymph nodes and Stage IV denotes distant metastatic disease [34, 35] (Table 26.3).

Table 26.3

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging for duodenum/ampulla/jejunum/ileum carcinoid (7th edition)

Primary tumor (T) | |

|---|---|

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

T1 | Tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa and size 1 cm or less* (small intestinal tumors); tumor 1 cm or less (ampullary tumors) |

T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria or size >1 cm (small intestinal tumors); tumor >1 cm (ampullary tumors) |

T3 | Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into subserosal tissue without penetration of overlying serosa (jejunal or ileal tumors) or invades pancreas or retroperitoneum (ampullary or duodenal tumors) or into non-peritonealized tissues |

T4 | Tumor invades visceral peritoneum (serosa) or invades other organs |

For any T, add (m) for multiple tumors | |

*Note: Tumor limited to ampulla of Vater for ampullary gangliocytic paraganglioma | |

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

|---|---|

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

Distant metastases (M) | |

|---|---|

M0 | No distant metastases |

M1 | Distant metastasis |

Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIA | T2 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIB | T3 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIA | T4 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIB | Any T | N1 | M0 |

Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

TNM staging system for carcinoid tumors of the colon and rectum is as follow: T1 are lesions that have not invaded the muscularis propria and ≤2 cm in size, T2 are lesions that have invaded the muscularis propria or >2 cm in size with invasion of lamina propria or submucosa, T3 are those that invade through the muscularis propria into the subserosa or into non-peritonealized pericolic or perirectal tissues, and T4 are those that invade peritoneum or other organs. Stage 1 is T1N0M0; stage 2 is T2N0M0 or T3N0M0; stage 3 is T4N0 or evidence of nodal disease, regardless of T-stage; and stage 4 is evidence of distant metastasis (Table 26.4). Lung carcinoid tumor is staged the same as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Table 26.4

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging for colorectal carcinoid (7th edition)

Primary tumor (T) | |

|---|---|

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

T1 | Tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa and size 2 cm or less |

T1a | Tumor size less than 1 cm in greatest dimension |

T1b | Tumor size 1–2 cm in greatest dimension |

T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria or size more than 2 cm with invasion of lamina propria or submucosa |

T3 | Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into the subserosal or into non-peritonealized pericolic or perirectal tissues |

T4 | Tumor invades peritoneum or other organs. For any T, add (m) for multiple tumors |

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

|---|---|

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

Distant metastases (M) | |

|---|---|

M0 | No distant metastases |

M1 | Distant metastasis |

Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIA | T2 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIB | T3 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIA | T4 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIB | Any T | N1 | M0 |

Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Carcinoid tumors can also be classified into one of the three stages: localized disease, regional spread and distant disease. In a localized carcinoid tumor, disease is confined within the wall of the primary organ, such as the stomach, colon, or intestine. Tumors with regional spread include spread through the wall of the primary organ to nearby tissues, such as fat, muscle, or lymph nodes. Finally for distant spread, the carcinoid tumor has spread to tissues or organs far away from the primary organ, such as the liver, bones, or lungs.

Genetic and Prognostic Factors

The genetic alterations leading to carcinoid tumorigenesis is an ongoing scientific investigation. Pancreatic NETs are associated with numerous genetic syndromes such as MEN-1, von Hippel-Lindau, neurofibromatosis type 1, and tuberous sclerosis [36]. More in-depth discussion of this topic is found in Chap. 24, Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PNETs). Genomic aberrations in gastrointestinal carcinoids seem to be fewer than those seen in pancreatic NETs, which suggests a different molecular pathogenesis. Loss of heterozygosity mutations of chromosome 18 are the most common genetic abnormality [37]. The most frequently reported mutated gene in gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors is beta-catenin, which plays an important role in the Wnt signaling pathway. Cyclin D1 and cMyc overexpression have also been reported in these tumors, while a set of genes (NAP1L1, MAGE-2D, and MTA1) has been correlated with malignant behavior of small intestinal carcinoids [38].

For appendiceal carcinoids, tumor characteristics that predict aggressive behavior include tumor size greater than 2 cm, mesoappendiceal involvement, and histologic subtype [39]. Mesoappendiceal invasion has been shown to correlate with malignant potential and nodal spread in tumors less than 2 cm in size [40].

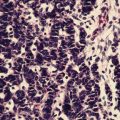

The World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed a tumor grading system for neuroendocrine tumors based on mitotic rate and the Ki67 proliferation index where G1 is Ki67 ≤ 2 % or mitotic count <2/10 high powered fields (HPF), G2 is Ki67 3–20 % and mitotic count 2–20/10 HPF, and G3 if Ki67 > 20 % and mitotic count >20/10 HPF [41] (Table 26.5). Multi-institutional studies have demonstrated increasing age at diagnosis, plasma chromogranin A levels, high tumor volume, and Ki67 level to be associated with a poorer prognosis [42].

Table 26.5

World Health Organization Grading System for Neuroendocrine Tumors

Grade | Mitotic count per 10 HPF | Ki-67 index (percent) |

|---|---|---|

G1 | <2 | ≤2 |

G2 | 2–20 | 3–20 |

G3 | >20 | >2 |

For bronchial carcinoids, atypical histology predicts a poorer outcome as these tumors have higher mitotic rates as well as nodal metastases with an overall 5-year survival of 60 %. In gastric carcinoids, type 3 tends to be larger and more likely to have metastatic spread than types 1 and 2; it carries a 50 % 5-year survival rate. Type 4 gastric carcinoids tend to be unresectable at the time of presentation and carry the poorest outcome. Colorectal carcinoid tumors tend to be diagnosed later than small bowel carcinoid tumor and are associated with a worse prognosis (5-year survival 40–50 %).

Medical Management of Advanced Disease and the Carcinoid Syndrome

Patients with metastatic disease to the liver are more likely to develop carcinoid syndrome, a clinical situation that is a result of the overproduction of biologically active substances and hormones produced by carcinoid tumors and secreted directed into the systemic circulation. Although nonmetastatic carcinoids can secrete bioactive products, these products are inactivated by the liver as they enter the portal circulation. Thus, nonmetastatic carcinoids do not generally produce carcinoid syndrome, except for ovarian and bronchial carcinoids, which can secrete bioactive hormones directly into the systemic circulation.

Symptoms associated with the carcinoid syndrome include flushing, bronchospasm, hypotension, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, or even right-sided heart failure. It occurs in only 5 % of patients with carcinoid tumors. In the past, supportive care was the mainstay of treatment. Bronchodilators were prescribed for bronchospasm and wheezing. Antidiarrheals such as loperamide were used for diarrhea, although severe cases were sometimes given cyproheptadine which decreased diarrhea in up to 50 % of patients [43]. Heart failure was treated with diuretics and if severe, valve replacement.

Modern management of carcinoid syndrome and advanced carcinoid tumors involves surgical resection and debulking of identified disease combined with medical management of unresectable disease utilizing a multidisciplinary approach. Somatostatin analogs (SA) have been the mainstay of medical therapy for advanced carcinoid tumors. These substances inhibit the symptoms of carcinoid syndrome quite effectively in many patients. Octreotide is administered by subcutaneous injection every 6–12 h and has a half-life of approximately 90 min [44]. Numerous retrospective studies exist suggesting that a partial response to SAs are demonstrated in less than 10 % of patients and stable disease is seen in 40–87 % of patients without evidence of prior disease progression [45–50]. In addition to standard octreotide injections, long-acting depot injections are available and provide an excellent option for patients requiring long-term maintenance therapy.

The placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors (PROMID) study group presented a compelling randomized control trial with evidence of enhanced disease-free survival in patients receiving octreotide long-acting repeatable (LAR) injections compared to placebo. The median time to tumor progression was 14.3 months in the octreotide LAR group compared to 6 months in the placebo group [51]. The benefit was most pronounced in those patients who underwent primary resection and those with a lower hepatic tumor burden.

Interferon-alpha (IFN-α) has also been explored as a second-line therapy for patients with carcinoid symptoms refractory to SA monotherapy. Prospective, randomized data exists demonstrating a statistically insignificant increase in survival with combination therapy versus SA therapy alone (5-year survival 57 % vs. 37 %) [52]. There did appear to be a significantly reduced risk of tumor progression with combination therapy. Several other studies of IFN-α have similarly failed to demonstrate significant progression-free and long-term survival advantage to combination treatment over SA monotherapy and increased side effects in the groups receiving IFN-α [53–55].

Chemotherapy has been evaluated in multiple phase II clinical trials evaluating single agent regimens as well as combination regimens utilizing agents such as 5-fluorouracil, streptozocin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. Results have overall been poor, with no trial demonstrating a sustained partial response rate greater than 15 % [56–58]. Trials have been reported using hepatic arterial vascular occlusion therapy in selected patients with metastatic disease to the liver [59–67]. Tumor responses were observed in up to 60 % of patients with a reduction in biochemical symptoms in 12–75 % of patients [65, 67].

Novel agents utilizing targeted radiotherapy such as [111In-DTPA-D-Phe] octreotide, yttrium-labeled compounds [90Y-DOTATOC], and lutetium-labeled SA analogs [177Lu-DOTA0, Tyr3] octreotate have shown promise for the treatment of metastatic or inoperable carcinoid tumors. Indium-labeled compounds have shown response rates between 13 and 20 %, symptomatic improvement in 60 % of patients, and biochemical responses in as high as 80 % of subjects [68–71]. Yttrium-labeled compounds have shown a similar tumor regression in 14 % of patients with stable disease in an additional 41 % of patients [72, 73]. The newest SA radiolabeled analog, lutetium, has shown the most promising results with one study reporting a 48 % tumor regression 3 months after therapy [74, 75].

Recently, bevacizumab (vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor) has been explored as a target for carcinoid therapy. Patients with metastatic or unresectable carcinoid tumor on octreotide therapy were randomized to receive bevacizumab or pegylated IFN-α. Progression-free survival was significantly higher in the bevacizumab group (95 %) when compared to the pegylated IFN-α group (68 %) at 18 weeks [76].

Phase 3 trials in patients with advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors have shown that the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, everolimus, significantly increased median progression-free survival versus placebo when used in addition to octreotide LAR (16 months vs. 11 months) [77]. Although everolimus has shown potential benefit in progressive pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, it has not yet been used in the treatment of carcinoid tumors.

Principles of Surgical Resection by Site

Bronchopulmonary Carcinoids

Bronchopulmonary carcinoid tumors account for approximately 2 % of lung neoplasms. As high as 25 % of well-differentiated NETs are located in the bronchopulmonary tree [78]. Carcinoid syndrome occurs in less than 2 % of patients who present with pulmonary carcinoid compared to 10 % of patients presenting with a gastrointestinal tract primary [79]. The overall prognosis of pulmonary carcinoid depends heavily on the underlying histological appearance, typical versus atypical carcinoid. Atypical carcinoid tumors have increased mitotic activity, nuclear pleomorphism, and tumor necrosis while typical carcinoid tumors have more organized architecture and rarely show mitotic figures [80].

Typical carcinoid tumors behave more indolently than atypical carcinoid tumors, but lymph node metastasis does occur in 10–15 % of cases with distant metastatic disease occurring in 3–5 % of cases [81, 82]. The 5-year survival rate exceeds 90 % following resection. In contrast, atypical carcinoids have nodal metastases 50 % of the time, distant metastases 20 % of the time, and a 5-year survival of 60 % [83].

The standard surgical treatment for bronchial carcinoids involving complete surgical resection with regional lymphadenectomy [84]. Lobectomy is most often required, but lung-sparing operations such as a sleeve resection or wedge resection can occasionally be adequate. Endoscopic resection is typically inadequate and is associated with high recurrence rates [79]. In cases where resection is not possible, palliation can often be achieved with external beam radiation where a course of 45–50 Gy can achieve partial responses in many cases but long-term responses are not expected. Additionally spinal or bone metastases often will respond to XRT while liver metastases do not.

Gastric Carcinoids

Gastric carcinoid tumors compromise 20 % of gastroentero-pancretic NETs and 1 % of gastric neoplasms [85]. These tumors are divided into four distinct types based on clinical presentation and histological features (Table 26.6). Type 1 gastric carcinoid tumors are typically small and behave in a benign fashion [86]. These tumors are the most common type of gastric carcinoid tumors (75 %) and are associated with chronic atrophic gastritis and hypergastrinemia. Most type 1 tumors are <2 cm and are amenable to endoscopic resection if endoscopic ultrasound does not demonstrate regional lymph node involvement or wall invasion [87, 88]. Yearly endoscopic surveillance is recommended because these lesions are highly recurrent. Surgical excision is recommended for larger type 1 tumors >3 cm due to their higher malignant potential and those tumors that are demonstrated to be invasive. For patients with multiple type 1 gastric carcinoids, somatostatin analogs have been shown to halt regression and prevent recurrence [89, 90]. Death as a result of type 1 lesions is uncommon.

Table 26.6

Characteristics of subtypes of gastric carcinoids

Type | Gastrin level | Treatment | Prognosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Type 1 | Most common (70–80 %) | High in response to gastric achlorhydria | Endoscopic resection for tumors ≤2 cm | Good |

Tend to be small and multiple | Gastrectomy for tumors >3 cm or suspicious for invasion | |||

Associated with chronic atrophic gastritis and hypergastrinemia | Somatostatin analog | |||

Type 2 | Occurs in 5 % of gastric carcinoids | High due to gastrinoma from MEN or ZES | Resection | Good |

Associated with MEN and ZES | Somatostatin analog | |||

Tend to be small and multiple | ||||

Type 3 | Occurs in 20 % of gastric carcinoids | Normal | Treat like gastric adenocarcinoma (gastrectomy and lymph node dissection) | 50 % 5-year survival for nonmetastatic |

Sporadic type | ||||

Tend to be solitary lesion | 15 % 5 year survival for metastatic | |||

Aggressive |

Type 2 gastric carcinoid lesions are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. These tumors tend to be somewhat larger than type 1 tumors, but also usually behave in a benign fashion. Often patients will present with multiple tumors [90]. Surgical treatment is aimed at correcting the hypergastrinemia by resection of the gastrinoma as long as the lesions do not demonstrate invasion. Somatostatin analogs are used to halt tumor growth for this type of gastric carcinoid as well [91]. Death due to type 2 gastric carcinoid tumors is rare, but these tumors do require yearly surveillance similar to type 1 tumors.

Type 3 gastric carcinoid tumors arise sporadically in the setting of a normal gastrin level and gastric pH, unlike type 1 and type 2 carcinoid tumors. These tumors tend to behave similar to gastric adenocarcinoma and are usually 3–5 cm at the time of their discovery [92]. Most of these tumors show infiltration into the gastric wall. Treatment for type 3 lesions involves surgical resection which may require subtotal or total gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy [93]. Five-year survival for type 3 gastric carcinoid tumors is 50 % overall and 15 % in those that present with metastatic disease [94]. Type 4 gastric carcinoids are poorly differentiated neuroendocrine cancers that will often present with disseminated disease at the time of diagnosis. Curative surgical therapy is usually not possible, but surgical debulking with chemotherapy can be considered in selected patients.

Jejunoileal Carcinoids

Carcinoid tumors of the small intestine tend to progress slowly with an extended disease course. These tumors often will present with symptoms of obstruction or ischemia and are typically located within the distal ileum. Five-year survival rates are 50–60 %; however, the prognosis is better in patients who present with localized disease (5-year survival of 80–90 %) than those who present with lymph node metastasis or distant spread (5-year survival 70 % and 55 %, respectively) [94]. The histological grading of the tumor is also important in the overall prognosis. Tumors with low Ki-67 and well-differentiated tumors show an overall survival advantage [55]. Although surgical resection can relieve symptoms, patients must have lifelong surveillance due to the high risk of recurrence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree