Andrea Valeri, Carlo Bergamini, Ferdinando Agresta and Jacopo Martellucci (eds.)What’s New in Surgical OncologyA Guide for Surgeons in Training and Medical/Radiation Oncologists10.1007/978-88-470-5310-6_17

© Springer-Verlag Italia 2013

17. Cancers of Unknown Origin

(1)

Medical and Surgical Scineces, University of Brescia, Italy

(2)

Local Healthcare Unit ULSS 19 — Veneto, Adria, Italy

(3)

Division of General Surgery, Andosilla Hospital, Civita Castellana (Viterbo), Italy

(4)

Laparoscopic Surgical Unit, M.Mellini Hospital, Chiari (Brescia), Italy

Abstract

Cancers of unknown primary origin (CUP), or occult primary tumors, are malignancies, documented in a metastatic localization, without an identified primary origin. This malignant syndrome accounts for approximately 3–5% [1,2] of all cancer diagnosis. An estimated 31,000 patients have been diagnosed with an occult primary tumor during 2001 in the USA [3]. An analysis of the Swedish Family-Cancer Database demonstrated that incidence of CUP was between 6.00 and 6.98 cases per 100,000 from 1987 to 2008 [4]. Herein we report new developments in the diagnosis and treatment of CUP.

Cancers of unknown primary origin (CUP), or occult primary tumors, are malignancies, documented in a metastatic localization, without an identified primary origin. This malignant syndrome accounts for approximately 3–5% [1,2] of all cancer diagnosis. An estimated 31,000 patients have been diagnosed with an occult primary tumor during 2001 in the USA [3]. An analysis of the Swedish Family-Cancer Database demonstrated that incidence of CUP was between 6.00 and 6.98 cases per 100,000 from 1987 to 2008 [4]. Herein we report new developments in the diagnosis and treatment of CUP.

Introduction

The definition of cancers of unknown primary origin (CUP) varies among authors because a uniform set of inclusion and exclusion criteria is not available. Almost one-third of advanced tumors is diagnosed after its metastases have been discovered. In some of those cases, the organ site of the primary lesion becomes evident shortly thereafter, upon completion of a first set of clinical, pathological and imaging evaluations; those patients should be treated accordingly to a specific protocol. An extensive diagnostic workup determines the origin of some of those neoplasms; however, it is estimated that a primary site is eventually found in <30% of patients who present initially with an occult primary tumor. In 20% to 50% of cases, the primary tumor is not identified even after post mortem examination [5,6].

Guidelines [7] set by the UK National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in 2010 provide some practical definitions related to the stage of the workup. A metastatic malignancy without an obvious primary site, before comprehensive investigation, is called a “malignancy of undefined primary” (MUO). If a careful review of histological specimens (or cytological specimens for pleural effusions or ascites) can then exclude non-epithelial tumors (melanoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, germ cell) and a selected initial screen of investigations (complete history and physical examination, routine laboratory tests, chest radiograph, routine imaging and endoscopy guided by signs, symptoms or laboratory abnormalities) cannot identify the primary source, the tumor is defined as a “provisional carcinoma of unknown primary” (“provisional CUP”). Only after specialist review and further appropriate specialized investigations, the lesion should be defined as metastasis of an occult primary tumor and termed “confirmed carcinoma of unknown primary” (“confirmed CUP”).

The classification described above constitutes a straightforward and practical framework. However, it cannot account for the lack of consensus about the basic tests required in the initial diagnostic phase, and for the extreme complexity and variability of the “specialized investigations” available today.

In fact, many technological advances have been proposed as an aid in the diagnosis of CUPs, and several of them have been introduced in clinical practice. An initially confirmed CUP can be attributed to a putative origin by a more sophisticated level of diagnosis, even without anatomical localization of the original tumor. Typically, the quest for a primary origin of an occult lesion may include positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), immunohistochemistry (IHC), assessment of serum markers and gene-expression profiling essays. Interestingly, research on this topic has focused on the relationship between the metastatic lesion and the original tissue, but is far from being established if thorough identification of the histological origin translates into a better outcome [8]. Recent research shows that cancers originating from the same tissue or organ do not necessarily respond to therapy in the same manner, and specific genetic factors can influence the response to treatment. This is particularly true for CUPs (with the exception of the most favorable subsets), which seem to behave more aggressively than metastatic tumors whose origin is known.

Recent Technological Developments that Aid Diagnoses

A comprehensive coverage of the diagnostics for CUPs is beyond the scope of this chapter, which focuses on the role of surgery. Technological advances in the diagnosis of CUPs are among the most important achievements in recent research on this topic. Their impact on outcome has yet to be demonstrated, but their potential influence on the knowledge of tumor biology (and even therapy) should not be underestimated. New biological and pathological features (including IHC profiling and gene expression-based assays) could be integrated, in the future, in algorithms to better define subsets of patients who could benefit from specific treatments, targeted to the identified tissue of origin, or even addressing the genomic abnormalities responsible for a certain behavior of the tumor itself. All this body of knowledge will certainly have an impact on the role of surgery in the treatment of these situations.

Immunohistochemistry

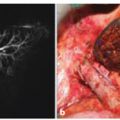

In general, hematoxylin and eosin staining can be used to determine the diagnosis, but the role of IHC has been increasing in recent years. Most guidelines consider at least a limited IHC study to be necessary for the diagnosis of CUP to exclude a non-epithelial origin of the lesion and to determine the origin of a carcinoma. IHC can accurately predict the origin of ≈35–40% metastatic cancers [9]. We cannot examine all the suggested IHC stains, but screening panels including cytokeratins (CK-7, CK-20), thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) and breast/ovarian markers are taken into consideration in most guidelines. Some authors have identified a new favorable subset of patients called “adenocarcinoma with colon cancer profile” that have a specific pattern of keratins and tumor-specific antigens (CK20+, CK7., CDX2+). This subset responds to colon cancer-specific combination chemotherapy regimens with a median survival of 20–24 months [10]. Even if experiences on the surgical treatment of this subset have not been published, a role for hepatectomy in selected patients showing this IHC pattern can be foreseen.

Molecular Profiling

Different organ tissues show different patterns of gene expression, with some genes showing greater expression in one organ than another. The specific pattern of gene expression constitutes a “signature” of that tissue. Neoplasms share some of the patterns of the original tissue. Cell type-specific differential gene expression profiles have been used to develop assays that can provide additional information for the classification of tumors, including unknown primary cancers. The accuracy of the classification of these assays is >80% [11]. Multiple gene signatures for the prediction of primary sites have been generated, and there are several commercial tests available using this technology. All of them can be used to identify accurately types and subtypes of cancer on specimens with extremely low numbers of neoplastic cells. The ability to detect tumor signatures on particularly small specimens is extremely relevant for reducing the invasiveness of the diagnostic phase. A molecular profile consistent with six primary sites (lung, breast, colon, ovary, pancreas, and prostate) has been found, evaluating the expression of a 10-gene panel [12], and 10 cancer types could be distinguished by a second panel using 495 predictive genes [13]. Even though validation of this method to predict the origin of a CUP has not been established, its potential role in typing an otherwise “orphan” tumor (and even in determining specific drug response signatures) is enormous.

Advances in Imaging Methods

The widespread availability of complex (but highly effective) technologies such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) means that these imaging modalities are included in most diagnostic protocols for CUPs. The same definition of “putative CUP” cannot be obtained from a chest and abdominal multislice spiral CT, and MRI is often used in the diagnosis of occult tumors of the breast, head or neck.

The need to localize exceptionally small tumors, however, has prompted considerable interest in 18-F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18-FDG-PET), especially if combined with CT (PET-CT). CUPs are supposedly too small to be detected in the initial investigation phase, which generally includes CT. The ability of PET-CT to provide functional and metabolic information, along with the imaging, makes this technology particularly useful [14]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated the excellent sensitivity and specificity of PET-CT in the localization of the primary tumor of an occult metastasis [15]. However, FDG remains a rather non-specific agent that can also accumulate in non-neoplastic tissues. Several other radiotracers are being evaluated for use in PET-CT to enhance its specificity [16,17]. Clinical use of tracers aimed at specific molecular tumor targets and the use of PET-MRI could induce substantial changes to the approach to these tumors.

Overview of Surgical Treatment

It could be argued that the role of surgery is extremely limited in a disease that, by definition, is already diffuse at diagnosis and whose biology is probably more aggressive for its early metastatic potential. However, such heterogeneous conditions can be divided into subsets with relatively homogeneous clinicopathological features. Most patients have aggressive disseminated disease that is relatively resistant to chemotherapy and with little curative potential, but 15–20% of subjects belong to subsets with a more favorable prognosis for whom a better outcome can be achieved [18].

Examining this topic under an evidence-based prospective is very difficult. Obtaining a series large enough to achieve a solid level of evidence for each of the significant subsets is not easy in such a heterogeneous group of conditions. Moreover, as research advances and our ability to determine the origin of the tumor increases, more lesions become associated with their putative primary origin, sometimes even if their diagnosis is likely but, in fact, uncertain. These lesions are often studied within a specific group of tumors and excluded from the CUP series (which are left only with unidentified cases). The same technological progress does not allow consideration of series collected over a long timespan because it is extremely likely that the diagnostic methods used in the most recent cases were not available for patients enrolled just few years earlier, making the group inhomogeneous. This is probably the only situation in which the passing of time does not help in accruing larger and more significant series and obtaining a better level of evidence.

Even with the limitations mentioned above, several organizations have recently issued guidelines for the diagnosis and management of CUPs [7, 19– 21] using different methodologies.

A complete and detailed overview of all the diagnostic and multidisciplinary treatments of CUPS lies outside the scope of this chapter. Complete diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms can be found in the guidelines mentioned above. There is no question, however, that identification of potentially treatable anatomoclinical entities, in which it is possible to obtain long-term disease control with appropriate multidisciplinary management, has been one of the most relevant scientific achievements in this matter. Surgery plays a pivotal role for some of these subsets. We will examine the treatment of these subsets but not discuss those with minimal surgical interest.

Women with Papillary Adenocarcinoma of the Peritoneal Cavity

Ascitic fluid is a common manifestation of CUP. Cytology is sometimes sufficient to provide the diagnosis. In other cases, imaging can show definite peritoneal or omental implants that can be subjected to percutaneous ultrasoundguided biopsy. Diffuse peritoneal disease, without bulk localizations and a negative cytological diagnosis, require diagnostic laparoscopy and biopsy.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis, with papillary serous histology (serous papillary carcinoma), is considered to be consistent with ovarian histology even in the absence of ovarian involvement and, as such, is treated. Serum levels of cancer antigen Ca125 is elevated in ≈80% of cases. The origin of this type of tumor (and also of the “ovarian” cancer) is incompletely understood, and several theories have been proposed based on morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular findings [22]. Clinical reports seem to suggest that ovarian cancer and serous papillary carcinoma behave as distinct (although similar) entities [23]. As ovarian carcinoma, this condition is highly sensitive to platinum- based chemotherapy, and all guidelines agree that it should be treated as FIGO stage III ovarian cancer, with aggressive surgical cytoreduction followed by platinum-based postoperative chemotherapy. This indication is based on the analogy with ovarian cancer and to the fact that the outcome after cytoreduction and chemotherapy is similar to that obtained in the stage-III and -IV ovarian cancer [24].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree