and Karl Reinhard Aigner3

(1)

Department of Surgery, The University of Sydney, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(2)

The Royal Prince Alfred and Sydney Hospitals, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(3)

Department of Surgical Oncology, Medias Clinic Surgical Oncology, Burghausen, Germany

In this chapter, you will learn about:

Cancer of the penis

Cancer of the testis

Cancer of the prostate gland

16.1 Cancer of the Penis

Penile cancer is uncommon, particularly in Western societies. It is almost unknown in Jewish males who are circumcised soon after birth but is a little more common in Muslim males who are circumcised at about 10 or 12 years. Most that are seen are in uncircumcised men. Lack of genital hygiene and cleanliness may be a factor or sometimes this cancer is associated with the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus.

It is essentially a squamous cell cancer similar to the common skin cancers but somewhat more aggressive. It tends to spread rather more readily to draining lymph nodes in the groins than is usual for other squamous cancers of the skin.

Most cases are first seen when a small crusty, papillomatous or small ulcerated skin lesion is present, and these can usually be well treated by surgical removal of the lesion, keeping a close watch on draining groin lymph nodes thereafter. Occasionally very advanced cases are seen, usually in men living in remote places or undeveloped communities. These usually respond well to induction chemotherapy especially if given by intra-arterial infusion. Involved lymph nodes should be surgically resected. A series of quite spectacular responses of very advanced cancers on the penis have been reported from Taiwan using intra-arterial infusion chemotherapy, followed by surgery or radiotherapy. A high incidence of cure was reported.

16.2 Cancer of the Testis

Testicular tumours are not common but when they do occur they are almost always malignant. Most occur in young adult males between the ages of 18 and 40. They are almost all classified as “germ-cell” tumours. Germ cells are embryonic type cells capable of developing into different cell types. Germ-cell cancers are uncommon, but they occur most often in a testis. Occasionally they occur in midline structures like the mediastinum or retroperitoneum or pineal gland usually in children or young adults. Some cancers of the ovary are also germ-cell cancers.

There are no known causes of testicular cancer. They are more common in developed than developing countries but the reason for this is not known. They are distinctly more likely to occur in undescended testes. Cryptorchidism is a condition in which the testes have not descended from the abdomen, where they develop, into the scrotum where they should be present at birth. If one or both testes are not present in the scrotum of infant boys, they are retained in the abdomen or the inguinal canal or somewhere nearby. Surgical operation (orchidopexy) should be performed before the age of 8 or 10 to place the testes into their normal position. This will reduce the risk of development of testicular cancer sometime later in life, after puberty. It is postulated that the warmer temperature of the testes in the abdomen may be responsible for the increased risk of testicular cancer in undescended testes.

Similarly there is an increased risk in men with Klinefelter’s syndrome. This is an abnormal genetic condition in which rather than having XX or XY sex chromosomes, the affected individuals have three chromosomes, XXY. This gives some female characteristics in otherwise apparently tall, thin, underdeveloped males with small underdeveloped testes that are more prone to malignant change.

16.2.1 Presentation

Cancer of the testis is usually found as a painless and non-tender swelling of a testis.

Cancer of the testis is usually found as a painless and non-tender swelling of a testis although occasionally the swelling is tender and possibly painful. Occasionally no swelling is noticed in the testis until there is evidence of metastatic spread of a cancer. Metastases may be noticed as a mass of enlarged and sometimes tender lymph nodes in the abdomen; enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, usually the left side known as Virchow’s nodes (Sect. 5.4); or as metastases in the lungs seen in chest X-rays. Occasionally the first evidence of a testicular cancer may be swelling of a man’s breasts due to hormonal changes. In other patients the first evidence may be of general debility, anorexia (loss of appetite) and weight loss.

16.2.2 Investigations

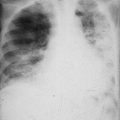

If a swelling is detected in a testis, ultrasound of the testis will help confirm if a solid tumour is present. If found, it is almost always a cancer. In such cases investigations are carried out to look for evidence of metastatic spread. CT scans and excretory urograms (IVP X-rays described in Sect. 7.3.2) may be helpful in detecting any enlarged lymph nodes in the abdomen. Chest X-rays may help detect metastases in the lungs or in lymph nodes in the chest (mediastinal lymph nodes).

An operation is recommended to confirm the diagnosis and allow the testis to be examined and removed if a tumour is clearly present.

16.2.3 Pathology

A number of tumour markers in the blood will help detect and classify testicular cancers.

There are two broad types of testicular cancer, of about equal incidence, seminomas and non–seminomas most of which are teratomas. Seminomas tend to occur in slightly older age groups (mean 35 years) and are very sensitive to radiotherapy. Non-seminomas, or non-seminoma germ-cell tumours (NSGCT), often contain a mixture of histologies including embryonal and yolk sac carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, teratomas and seminomas. They are most often in younger age groups (mean 25 years) and are less sensitive to radiotherapy but are highly responsive to chemotherapy.

A number of tumour markers in the blood will help detect and classify testicular cancers and so indicate most appropriate treatment and help assess response to treatment. Alpha-foetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) can all be useful testicular cancer markers. If the level of a tumour marker is elevated, it helps establish a diagnosis of tumour type, and if the level falls to normal after treatment, it indicates a good response to treatment and probably a cure.

16.2.4 Treatment

Cancer of a testis is treated by surgical removal of the testis (through an inguinal approach), and radiotherapy is given to draining lymph nodes in the abdomen or to any other lymph nodes likely to be involved, especially if seminoma was diagnosed.

In the case of teratoma even if the cancer is widespread into the lungs or elsewhere, good results, with a high proportion of long-term cures, are achieved with chemotherapy.

From being among the cancers with a poor prognosis a few years ago, with present-day integrated and combined treatment programmes using surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, testicular cancers are now among the most curable cancers.

Patients should be advised that it is still possible to lead a normal sex life and to father children with only one testis.

Exercise

Drawing on case reports in this chapter and other chapters of this book, construct a case report of a typical patient presenting with and being investigated and managed for a testicular cancer.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16.3 Cancer of the Prostate Gland

Almost all men over the age of 90 have microscopic evidence of at least early prostate cancer.

Cancer of the prostate is uncommon before the age of 45, but in Western countries, other than skin cancer, it is the most common cancer in men over the age of 65 and became increasingly common during the twentieth century, especially in the latter part of the twentieth century.

This rapid rise in recorded incidence is due in part to the use of the prostate-specific antigens (PSA) test for detecting early subclinical prostate cancers or “latent” prostate cancers that might not have otherwise progressed to a clinical stage. The rise in apparent incidence of prostate cancer after the common use of PSA as a screening test is somewhat similar to the increased numbers of early breast cancers in the 1980s and 1990s after common use of mammography as a screening test. However, the PSA test is much less specific for prostate cancer; a raised index simply indicates increased prostate cell activity that may be due to benign prostate disease, latent prostate cancer or established prostate cancer. Evidence suggests that early breast cancers are unlikely to remain “latent” for any length of time, but “latent” prostate cancer may well remain non-invasive indefinitely.

The cause of prostate cancer is largely unknown but its association with old age is illustrated by the fact that in Western countries almost all men over the age of 90 have microscopic evidence of at least early prostate cancer.

There is a familial association of prostate cancer especially in younger men (below 55 years) and some of these are linked to mutations of the BRCA2 gene (see Sects. 2.4 and 2.5). The increased familial association is greater if male relatives have had prostate cancer, but there is also some increase in families with a high incidence in men on the mothers’ side of the family.

There is also an increased risk in men with a history of prostatitis.

Prostate cancer is now the second most common cancer in males in Western countries, after skin cancers, and it is second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer death in men. In stark contrast epidemiological studies show that Asians, Africans and native Americans living in their traditional lifestyles have a low incidence of prostate cancer (see Appendix and Table 1).

The highest incidence is in black males in the United States followed by white males in the United States, Europe and other Western countries. The lowest incidence of prostate cancer is in men in India and Southeast Asia and also in black males living in Africa. Men of Asian or African ethnicity who have lived all their lives in Western countries have a high risk and in Afro-Americans an even higher risk than in white males of those countries. This suggests that causes are more closely related to environmental factors rather than racial or genetic factors. It is likely that differences in diet may play a part because prostate cancer is less common in communities that have predominantly vegetarian diets.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree