and Karl Reinhard Aigner3

(1)

Department of Surgery, The University of Sydney, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(2)

The Royal Prince Alfred and Sydney Hospitals, Mosman, NSW, Australia

(3)

Department of Surgical Oncology, Medias Clinic Surgical Oncology, Burghausen, Germany

In this chapter you will learn about:

Cancer of the oesophagus

Stomach cancer

Cancers of the liver

Primary liver cancer (hepatoma or hepatocellular carcinoma

Secondary (metastatic) liver cancer

Cancer of the gall bladder and bile ducts

Cancer of the pancreas

Cancers of the small intestine

Cancer of the large bowel (colon and rectum)

Cancer of the anus

13.1 Cancer of the Oesophagus

Cancer of the oesophagus is a comparatively common disease in Eastern Asia, especially China, and some African countries, particularly Southern African countries, including South Africa. It also has a relatively high incidence in males in France and Eastern Europe, especially Hungary (see Appendix). Although less common in Britain, America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the white population of South Africa, the incidence is rising in some of these countries, particularly in Britain. The reasons for this difference in incidence are not fully understood although consumption of alcohol and perhaps different diets play a part. In those parts of China and Africa that have a high incidence, a fungus that grows on stored food may be at least partly responsible. Oesophageal cancer is more common in men than in women especially in the middle and lower thirds of the oesophagus, but in the upper end, it is more common in women. Oesophageal cancer, like cancers in the mouth and throat, is more common in smokers and especially in smokers who are heavy drinkers.

Cancer of the lower end of the oesophagus is most often seen in people who have a history of inflammation or degeneration (metaplasia) or an ulcer in the lower oesophagus caused by long-standing regurgitation of stomach contents. Such an inflammatory degeneration with metaplasia in the lower oesophagus is now called Barrett’s oesophagus, but if an ulcer develops, it is known as Barrett’s ulcer. The conditions were first described by Dr Barrett, an Australian surgeon working in London. Barrett’s ulcer is becoming more common in Western countries, so too is cancer of the lower oesophagus.

13.1.1 Pathology

Most cancers of the upper and middle regions of the oesophagus are of the flat pavement or squamous cell type, having developed in the squamous mucosal lining. At the lower end of the oesophagus, where there may be glandular mucosa similar to that of the stomach, increasing numbers of cancers are of glandular-type cells. That is, adenocarcinoma is more common and increasingly so in association with long-standing Barrett’s ulcer.

13.1.2 Symptoms

Cancer of the oesophagus is usually well established before it is diagnosed.

Unfortunately, cancer of the oesophagus is usually well established before it is diagnosed. The most common symptom is dysphagia (difficulty with swallowing). First, there is difficulty in swallowing solid foods that seem to get caught in the throat or chest. Later, there is difficulty in swallowing liquids. A person with cancer of the oesophagus thus soon loses weight and may become quite wasted and even dehydrated.

13.1.3 Signs

The earliest sign of oesophageal cancer is for the doctor to observe the patient having difficulty with swallowing. A later sign will be evidence of weight loss and even dehydration.

13.1.4 Investigations

Barium swallow or barium meal X-rays (described in Sects. 7.3.2 and 7.3.3) will usually show an obstruction to swallowing in the oesophagus. An irregular, “apple-core”-shaped narrowing is a common feature at the site of this cancer.

Oesophagoscopy is carried out (described in Sect. 7.4.6), and through the oesophagoscope, the doctor can usually see an irregular tumour mass or an ulcerated tumour. A biopsy will establish the diagnosis microscopically.

Cancers of the oesophagus have usually spread up and down and under the mucous membrane lining of the oesophagus and into lymph nodes and other structures in the chest before the patient notices much in the way of symptoms. Thus, they are very often incurable when first diagnosed.

13.1.5 Treatment

Very early intramucosal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s oesophagus can sometimes be treated effectively by endoscopic resection. However, long-term cure of well-established or invasive oesophageal cancer is all too infrequent but the best hope of cure is by operation. The oesophagus is removed and either the stomach or a section of bowel is used to make a new oesophagus for passage of food.

Radiotherapy is also used to treat this cancer. Although it often makes a cancer smaller for a period and relieves symptoms temporarily, it does not often cure the cancer.

Even when radiotherapy and surgery are used together, results have been disappointing.

Chemotherapy alone has also been disappointing in treating this cancer.

The earliest attempts to improve results by using chemotherapy first to reduce the cancer and then surgery to remove the remaining cancer did not improve patient outcomes. However, more recently some encouraging results have been reported using different drug combinations in integrated treatment programmes in which chemotherapy has been integrated and synchronised with radiotherapy and possibly followed by surgery. Further studies are needed before a change in standard practice can be recommended with confidence.

Sometimes attempts at removing an oesophageal cancer are not possible, and the most helpful treatment is for the surgeon to pass a plastic tube through the oesophagus and past the cancer into the stomach, to allow the patient to swallow food through the tube. Otherwise, some alternative food passage, possibly by putting a feeding tube directly into the stomach, or another method of feeding, like intravenous nutrition, may be required.

Screening. Because of the increased risk of cancer of the lower oesophagus and upper stomach associated with Barrett’s metaplasia or Barrett’s ulcer, it is recommended that people with persistent or uncontrolled reflux or a known Barrett’s oesophagus be regularly screened by oesophagoscopy or endoscopy for early detection of any malignant change.

Case Report

Lower oseophageal cancer

Michelle is a 63-year-old nurse.

She was 59 years old when she first complained of reflux and “burning” in her lower oesophagus. It had been troubling her for some months or possibly a year when she first consulted her family doctor. Her doctor arranged oesophagoscopy that confirmed gastric reflux and some mucosal irritation suggestive of Barrett’s oesophagus. The doctor advised Michelle to avoid bending, to lose some weight, to elevate the head end of her bed and sleep with extra pillows under her head. He also prescribed an antacid medication. He asked Michelle to return for consultation in 3 months. Michelle explained that she was committed to working in an African mission for 2 years. The doctor then proscribed a “proton pump” medication for Michelle to take with her in case her symptoms were not distinctly better in 3 months. He advised Michelle to return to Brussels or another major centre for reassessment in no longer than 6 months.

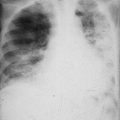

Initially Michelle got some relief from the antacid medication but symptoms returned so she took a course of the “proton pump” medication. It too gave her initial relief but symptoms returned and worsened. She continued with her work but eventually had trouble swallowing and lost a great deal of weight. After 13 months she returned to Brussels where her doctor arranged a further gastroscopy. An ulcer with raised edges was seen in the gastro-oesophageal junction. Biopsies showed it to be an adenocarcinoma. Chest X-rays and CT scans did not show any evidence of tumour spread.

Possible treatments were discussed with Michelle. She was advised that surgery alone would offer her no more than a 20 % chance of cure. Radiotherapy alone would probably give her temporary relief but an even less chance of cure. The specialist involved advised that his oncology group was taking part in a clinical trial using either pre-operative (induction) chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy or pre-operative chemotherapy followed by surgery to determine whether better results could be achieved.

Michelle agreed to take part in the study. After five treatments with chemotherapy at weekly intervals, her cancer had become significantly smaller. Surgical resection of the lower oesophagus and proximal stomach with draining lymph nodes was then performed, and the residual oesophagus was anastomosed to the remaining stomach in the chest.

After initial trouble with eating and some anaemia, Michelle is now taking smaller nutritious meals more frequently and some treatment for anaemia and is beginning to gain some weight. To date, 6 months post-operatively, she feels relatively well but has reduced energy. So far there is no evidence of cancer recurrence.

13.2 Cancer of the Stomach

Stomach cancer is uncommon before the age of 40, but thereafter, the incidence increases with age, reaching a peak between the ages of 60 and 65. For some unknown reason, in most countries males are affected about two or three times more commonly than females.

In the past, cancer of the lower or middle stomach was one of the more serious and more common cancers affecting mankind, but fortunately, over recent years, it has become less common.

Stomach cancer has distinct racial, geographic and dietary associations. It is about seven times more common in Japan and Korea and three or four times more common in Eastern Europe than in the United States (see Appendix).

Epidemiological studies suggest it has a direct close and relationship to diet. People who have a diet that is high in animal fats (especially chemically preserved meats) and low in fresh fruit and vegetables have a greater risk of developing stomach cancer. It may be related to a high intake of chemical food preservatives and other methods of food preparation, curing, storage and preservation. For example, the high intake of smoked fish in Japan has been incriminated. There is also a high incidence among people of northern Iceland who eat large amounts of crude smoked fish as opposed to a lower incidence in the people of southern Iceland who have a different diet. In Korea, the custom of eating a great deal of red pepper and possibly other irritating spices in food is thought to be significant.

It has been suggested that a reason for the decreasing incidence of stomach cancer in modern industrialised societies is the greater availability of fresh fruit and vegetables due to modern transport and the greater use of refrigeration to store foods rather than chemical preservatives and additives.

Medical conditions that increase a person’s risk of developing stomach cancer are pernicious anaemia (six times the normal risk), chronic gastritis, polyps in the stomach and gastric ulcers that may be due to Helicobacter pylori infection. Smokers also have an increased risk and the risk is greater in smokers who are also heavy consumers of alcohol.

13.2.1 Pathology

Having developed in gastric mucosa, most gastric cancers are glandular type (adenocarcinoma). In the past, gastric cancer was much more common in the lower stomach but the pattern is now changing. It is now becoming less common in the lower stomach and increasingly more common in the upper end, especially about the gastro-oesophageal junction. This change in pattern is at least partly due to effective treatment of the Helicobacter pylori bacillus that commonly caused ulceration and other mucosal changes in the lower stomach. Effective treatment of this infection appears to have reduced the incidence of cancer in the lower stomach.

13.2.2 Symptoms

Like cancer of the oesophagus, cancer of the stomach is usually quite advanced before pain or other symptoms cause most patients to seek medical attention. The earliest symptom is usually vague indigestion that gradually becomes worse and more persistent. Persistent indigestion occurring for the first time in someone over the age of 40 must always be considered with suspicion. Sometimes an early feature is loss of appetite especially for certain foods. Loss of appetite for meat is common. Other symptoms may be of fullness or even feeling “blown-up” in the stomach after eating small amounts of food or vomiting after food. Vomiting may become frequent, regular or blood stained. If a cancer has blocked the stomach, vomiting becomes persistent. Pain is sometimes the first symptom noticed, but when pain is persistent, the cancer is often quite advanced. Sometimes a patient has not been aware of any symptoms but has found a lump in the upper abdomen. Other patients feel weak and tired due to anaemia or have experienced recent unexplained weight loss that may be the reason they seek medical attention, rather than any particular indigestion or abdominal complaints. Occasionally the first evidence of trouble is due to the cancer having spread to other organs or tissues, for example, an enlarged liver or jaundice or back pain from the pancreas or other tissues behind the stomach.

13.2.3 Signs

Clinical examination may detect one or more of the following features: a swelling or lump in the upper abdomen, evidence of enlarged liver or lymph nodes, evidence of spread into the pelvis or onto an ovary (felt on vaginal or rectal examination) or evidence of fluid in the abdominal cavity (ascites). Evidence of anaemia or weight loss should also be checked. A palpable involved lymph node just above the medial end of the clavicle, and usually on the left side, is called Virchow’s node and is often a feature of advanced intra-abdominal cancer, especially stomach cancer, because these nodes drain lymph from around the thoracic duct which comes up from the abdomen.

13.2.4 Investigations

Blood tests for anaemia or other abnormalities and examination for blood in the faeces are standard investigations for possible cancer of stomach or bowel.

Endoscopy (or gastroscopy as described in Sect. 7.4) is a very useful test. Endoscopy may allow a cancer to be seen (as an ulcer with raised edges, a cauliflower-like mass or rigid abnormal distortion of the stomach wall) and a biopsy to be taken. Present-day endoscopy is now so readily practised and without stress to the patient that it is usually performed before barium meal X-ray studies.

A CT scan may be useful to determine the size and exact position of a cancer. It may show, for example, that the cancer has spread into the pancreas or liver or enlarged adjacent lymph nodes.

Barium meal X-rays (Sect. 7.3.2) may show an ulcer (usually with raised, rounded edges), or they may show a lump on the stomach wall looking something like a small cauliflower. The X-rays and screening may show a blocked stomach, a change in its shape or size (bigger, or shrunken and smaller) or a more rigid and stiff-walled stomach.

13.2.5 Treatment

The only present curative treatment of cancer of the stomach is surgery.

The only present curative treatment of cancer of the stomach is surgery: to remove all of the stomach (total gastrectomy), most of the stomach (sub-total gastrectomy) or part of the stomach (partial gastrectomy). Because of the high risk of lymph node involvement, draining lymph nodes are removed with the gastric resection.

If a cancer has already spread beyond the stomach region, surgical cure may not be possible, but it may still be possible to relieve symptoms, for example, a gastro-enterostomy to relieve stomach obstruction.

After total gastrectomy, the small intestine is anastomosed (joined) to the oesophagus or, in the case of a sub-total or partial gastrectomy, the small intestine may be anastomosed to the small remaining part of the stomach to allow food to pass through normally. After surgery the patient can eat only small meals and therefore needs to eat frequently to avoid too much weight loss. Without a stomach, the patient will also be given treatment to prevent anaemia. Anaemia may be a macrocytic anaemia due to loss of gastric intrinsic factor or a microcytic iron deficiency anaemia due to inadequate iron absorption or, possibly, blood loss.

In the past results of surgery alone in treating apparently resectable stomach cancers have been disappointing (about 25–30 % cures), but in general, the smaller a cancer is at surgery, the better the chance of cure. For this reason, endoscopy and other diagnostic tests may be used to look for evidence of cancer as soon as a patient complains of early symptoms. If the patient is a male over the age of 40 years, there is a greater risk that persistent symptoms of indigestion, lack of appetite and local epigastric pain and discomfort are due to a cancer. In some countries, and especially Japan, screening tests are often carried out in people at risk even though they may have no symptoms. When stomach cancers are found whilst they are small and in the early stages of the disease (as is now often the case in Japan), surgery results are good with a high rate of cure (more than 80 % cure rates have been reported). However, this is not often the case in Western countries where stomach cancer is less common and is not often diagnosed until troublesome symptoms have developed, by which time the cancers are more advanced and less likely to be cured by surgery alone.

Presently available anti-cancer drugs do not cure this cancer but they may be useful in treating people whose cancers cannot be cured by operation. The drugs will often make the cancers smaller and may give the patients good but temporary relief.

More recently, anti-cancer drugs have been given to some patients before the operation is carried out (see Sect. 8.3.4). Some reports have shown that if the cancers are made smaller by the drugs and then the operation (gastrectomy) is carried out, the results will be better and the chances of cure improved. The most effective way of giving the anti-cancer chemotherapy before operation may be by giving drugs directly into the coeliac axis artery that supplies blood to the stomach. After 5 or 6 weeks of this therapy, the cancer is usually smaller and, with following surgery, better results have been reported. These studies continue but as yet there has been no agreement about the most effective plan for integrated treatment.

More studies of these techniques are needed but there is some hope of better results with treatment of stomach cancer in the future: firstly, by earlier diagnostic tests to detect cancers at an earlier and more curable stage and, secondly, by the use of induction or neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery for those people who present for treatment with established, invasive, but removable cancers.

Studies in the use of post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy are in progress, but at the time of writing, although some positive results have been reported, there is no agreement on the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy.

After gastrectomy it is important to carefully follow up these patients not only for possible tumour recurrence but for general nutrition and to avoid both microcytic anaemia (possibly a feature of poor nutrition and iron deficiency) and macrocytic anaemia (due to loss of gastric intrinsic factor).

Exercise

List predisposing factors that may be associated with cancers of the stomach and the oesophagus.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

13.3 Cancers of the Liver

Cancers in the liver are either cancers that began in the liver cells (primary) or cancers that have spread to the liver from another primary site (secondary or metastatic).

13.3.1 Primary Liver Cancer (Hepatoma or Hepatocellular Carcinoma)

Cancer starting in liver cells (primary cancer) is uncommon in European races but is common in Africans, Southeast Asians, Chinese and Japanese (see Appendix). It ranges as high as half of all cancers in African Bantu men. The reasons for this difference in incidence are not completely understood although differences in diet and food storage and preparation are probably important. Long-standing liver infection with hepatitis B and hepatitis C and parasitic infestation, particularly by the liver fluke, are responsible for much of the increased incidence in some Asian countries. Certain fungi that commonly contaminate food in parts of Africa and Asia may also play a part, whereas food stored by refrigeration in Westernised societies should be free from fungus contamination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree