Major salivary gland malignancies are a rare but histologically diverse group of entities. Establishing the diagnosis of a malignant salivary neoplasm may be challenging because of the often minimally symptomatic nature of the disease, and limitations of imaging modalities and cytology. Treatment is centered on surgical therapy and adjuvant radiation in selected scenarios. Systemic therapy with chemotherapeutic agents and monoclonal antibodies lacks evidence in support of its routine use.

Key points

- •

Major salivary gland malignancies are a rare but histologically diverse group of entities.

- •

Establishing the diagnosis of a malignant salivary neoplasm may be challenging because of the often minimally symptomatic nature of disease, and limitations of imaging modalities and cytology.

- •

Treatment is centered on surgical therapy and adjuvant radiation in selected scenarios.

- •

Systemic therapy with chemotherapeutic agents and monoclonal antibodies lacks evidence in support of its routine use.

Salivary gland malignancies are rare tumors with an estimated population incidence of 1.2 per 100,000. These tumors constitute about 5% of all head and neck malignancies and tend to occur most frequently among men. Most salivary gland tumors arise in the parotid gland. Although benign neoplasms outnumber malignant tumors, most malignant salivary gland tumors involve the parotid gland; typically in the superficial lobe. The other major salivary glands, the submandibular and sublingual glands, have a higher proportion of malignant versus benign tumors, but these constitute a minority of all primary salivary malignancies.

The cause for malignant salivary gland tumors has not been clearly defined. Ionizing radiation may play a role in development of these malignancies. Tobacco and alcohol use have not been reliably proven to be causative in salivary gland malignancies. Similarly, exposure to wireless phones has not been associated with these tumors.

Histologic classification and staging

Salivary gland malignancies represent a cohort of varied histopathologic subtypes, and the revised World Health Organization (WHO) classification identifies 23 separate primary salivary gland malignant tumors ( Box 1 ). In addition, several tumors may show a spectrum of histologic grades that have disparate clinical profiles relating to their local aggression, risk for regional and distant metastases, and overall prognosis. The diverse nature and clinical behavior of these tumors pose unique difficulties in generating uniformity in staging and prognostic information.

Acinic cell carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma

Clear cell carcinoma, not otherwise specified

Basal cell adenocarcinoma

Sebaceous carcinoma

Sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma

Cystadenocarcinoma

Low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

Oncocytic carcinoma

Salivary duct carcinoma

Adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified

Myoepithelial carcinoma

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma

Carcinosarcoma

Metastasizing pleomorphic adenoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Small cell carcinoma

Large cell carcinoma

Lymphoepithelial carcinoma

Sialoblastoma

The current staging system offered by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) accounts for characteristics of the primary tumor (T stage), regional lymph node status (N stage), and presence or absence or distant metastases (M stage). However, the staging system does not factor the histologic grading of tumors, and fails to distinguish more indolent forms of disease from aggressive variants ( Table 1 ). Thus, staging information should not be the sole determinant of the management offered, and histologic information and other variables should be considered before assignment of treatment options and prognostication.

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| T1 | Tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension without extraparenchymal extension |

| T2 | Tumor more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm in greatest dimension without extraparenchymal extension |

| T3 | Tumor more than 4 cm and/or tumor having extraparenchymal extension |

| T4a | Moderately advanced disease Tumor invades skin, mandible, ear canal, and/or facial nerve |

| T4b | Very advanced disease Tumor invades skull base and/or pterygoid plates and/or encases carotid artery |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, 3 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2a | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2b | Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2c | Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node, more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

| Anatomic Stage/Prognostic Groups | |||

| Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage III | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| T1 | N1 | M0 | |

| T2 | N1 | M0 | |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| Stage IVA | T4a | N0 | M0 |

| T4a | N1 | M0 | |

| T1 | N2 | M0 | |

| T2 | N2 | M0 | |

| T3 | N2 | M0 | |

| T4a | N2 | M0 | |

| Stage IVB | T4b | Any N | M0 |

| Any T | N3 | M0 | |

| Stage IVC | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Histologic classification and staging

Salivary gland malignancies represent a cohort of varied histopathologic subtypes, and the revised World Health Organization (WHO) classification identifies 23 separate primary salivary gland malignant tumors ( Box 1 ). In addition, several tumors may show a spectrum of histologic grades that have disparate clinical profiles relating to their local aggression, risk for regional and distant metastases, and overall prognosis. The diverse nature and clinical behavior of these tumors pose unique difficulties in generating uniformity in staging and prognostic information.

Acinic cell carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Adenoid cystic carcinoma

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma

Clear cell carcinoma, not otherwise specified

Basal cell adenocarcinoma

Sebaceous carcinoma

Sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma

Cystadenocarcinoma

Low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

Oncocytic carcinoma

Salivary duct carcinoma

Adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified

Myoepithelial carcinoma

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma

Carcinosarcoma

Metastasizing pleomorphic adenoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Small cell carcinoma

Large cell carcinoma

Lymphoepithelial carcinoma

Sialoblastoma

The current staging system offered by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) accounts for characteristics of the primary tumor (T stage), regional lymph node status (N stage), and presence or absence or distant metastases (M stage). However, the staging system does not factor the histologic grading of tumors, and fails to distinguish more indolent forms of disease from aggressive variants ( Table 1 ). Thus, staging information should not be the sole determinant of the management offered, and histologic information and other variables should be considered before assignment of treatment options and prognostication.

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| T1 | Tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension without extraparenchymal extension |

| T2 | Tumor more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm in greatest dimension without extraparenchymal extension |

| T3 | Tumor more than 4 cm and/or tumor having extraparenchymal extension |

| T4a | Moderately advanced disease Tumor invades skin, mandible, ear canal, and/or facial nerve |

| T4b | Very advanced disease Tumor invades skull base and/or pterygoid plates and/or encases carotid artery |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, 3 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension; or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2a | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2b | Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N2c | Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node, more than 6 cm in greatest dimension |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

| Anatomic Stage/Prognostic Groups | |||

| Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage III | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| T1 | N1 | M0 | |

| T2 | N1 | M0 | |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| Stage IVA | T4a | N0 | M0 |

| T4a | N1 | M0 | |

| T1 | N2 | M0 | |

| T2 | N2 | M0 | |

| T3 | N2 | M0 | |

| T4a | N2 | M0 | |

| Stage IVB | T4b | Any N | M0 |

| Any T | N3 | M0 | |

| Stage IVC | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Presentation and work-up

Patients with major salivary gland tumors often present with an asymptomatic mass. Findings such as rapid increase in size of the mass, pain, and local soft tissue invasion suggest malignancy. In addition, facial nerve or other cranial neuropathy and presence of clinically evident regional adenopathy are strong predictors of a malignant process. Most patients have no specific clinical symptoms and the establishment of a malignant diagnosis requires additional investigations and/or invasive procedures.

Individuals presenting with a neoplasm of a major salivary gland should undergo a detailed history and physical examination. Historical features such as pain, trismus, skin changes, paresthesias, rapid growth, facial weakness, or other cranial neuropathies suggest a malignant neoplasm. Patients should be asked about history of skin malignancies, lymphoproliferative disorders, and autoimmune processes that may suggest a systemic secondary malignancy involving salivary tissue.

A comprehensive head and neck examination should include evaluation of the primary site (size of primary neoplasm, mobility of the mass, characteristics of overlying skin and soft tissue, and any extension to deep/parapharyngeal space), functional assessment of cranial nerves, and pathologic adenopathy in the draining nodal basins. Mucosal and cutaneous surfaces should be inspected for alternative sources of malignancy.

Imaging modalities should be directed at answering clinical questions and shaping the diagnostic and therapeutic pathways. The typical modalities used include ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and PET.

Ultrasonography is useful for anatomic and morphologic characterization of salivary gland tumors in the absence of deep parapharyngeal extension. In addition, it can assess regional nodes and assist guided aspiration biopsy where indicated. Ultrasonography is cost-effective and is often available in the outpatient clinical setting as an extension of the physical examination. Sonographic distinction of malignant neoplasms from benign masses may be possible, and malignancy should be suspected when features such as prominent heterogeneity in internal echo patterns, unclear borders, and increased internal vascular flow are seen. However, accuracy is diminished in small and low-grade malignant tumors. Other limitations of ultrasonography include its inability to identify and evaluate the parapharyngeal space, skull base, mandible, and perineural spread of tumor.

Cross-sectional imaging modalities, including CT scan and MRI, provide accurate localization and assessment of the extent of the tumor. These modalities assess nodal status and may provide clinically relevant information relating to neurotropic spread of tumor. MRI is considered the investigation of choice when a malignant neoplasm of a major salivary gland is suspected. Malignant tumors in the parotid are often less intense on T2-weighted images compared with benign counterparts. Other features on MRI that may point to a malignant tumor include ill-defined margins, infiltration of surrounding soft tissue, diffuse growth pattern, and pathologic lymphadenopathy.

PET-CT scans may not be useful in the initial assessment of salivary gland tumors for a variety of reasons, including inherent inability to distinguish between malignant and benign tumors, because many benign tumors accumulate fluorodeoxyglucose similarly to salivary malignancies. Moreover, PET-CT is cost intensive, and routine use is not advisable in the increasingly cost-sensitive health care environment. However, there is some evidence that, compared with conventional CT scans, PET-CT may provide a more accurate prediction of disease extent associated with a known high-grade salivary gland malignancy. It may also have some additional value in identification of locoregionally recurrent and metastatic disease.

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is variably incorporated by physicians in the management of major salivary gland neoplasms. The controversy relating to the utility of FNA is rooted in the histologic diversity shown by salivary gland malignancies. Several members of this morphologically complex group of malignancies may display close resemblance to histologically distinct entities. Although FNA has shown high sensitivity and specificity in several studies, these results may not be reproduced in community settings where experience with salivary cytology may be limited. Additional concerns about the ability of FNA to distinguish between benign and malignant salivary neoplasms persist. Despite reliable overall sensitivity and specificity of FNA, Colella and colleagues found that the final histopathology was discordant from the FNA results in more than 20% of salivary gland malignancies. Another study recognized that FNA might miss the malignant nature of salivary mass in 40% of cases investigated. In contrast, false-positives may lead to unnecessary interventions.

FNA could be significant in providing preoperative information distinguishing high-grade malignancies from low-grade malignant and nonmalignant disorders. This information may be critical in alteration of intraoperative management of high-grade malignancies, which differs from others in potential use of elective nodal dissection. However, Zbaren and colleagues found that tumor grade could be predicted with accuracy in one-third of parotid carcinomas subjected to FNA; another study noted high sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy (94%, 99%, and 99%, respectively) in identifying high-grade malignancy. This information contributed to additional imaging or change in extent of surgery in most of the included patient cohort. Because of controversies related to routine use of FNA in major salivary neoplasms and its limitations, some investigators propose the use of image-guided core needle biopsies as an alternative strategy with acceptable safety.

Selected histologic subtypes of major salivary gland malignancies

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) is the most common malignant neoplasm of the major salivary glands. It represents nearly one-third of all malignancies involving the major salivary glands. MEC occurs most commonly in women in their third to seventh decades of life. Parotid gland is most frequently involved, followed by submandibular and sublingual gland in that order.

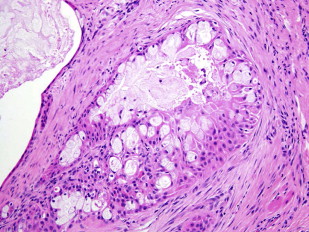

On histology, MEC is composed of mucin-secreting cells, intermediate cells, and epidermoid cells. Tumors vary in the proportion of cell types, degree of cellular maturation, and frequency of mitoses and neurovascular invasion, and degree of necrosis. In addition, tumor foci may show variable degrees of solid and cystic morphology. Mucoepidermoid carcinomas can therefore be classified as low-grade, intermediate-grade, or high-grade tumors. This differentiation is relevant to prediction of oncologic behavior, and affects choice and extent of therapy. A variety of grading systems, including 2 tiered (low and high grade) and 3 tiered (low, intermediate, and high grade), have been proposed; however, no system is universally accepted and they have traditionally been cumbersome to use.

Clinical presentation of MEC depends on histologic grade. Low-grade and intermediate-grade tumors often present as slow-growing, solitary masses with a lack of symptoms. In contrast, high-grade tumors may progress rapidly and may present with symptoms including pain, nerve deficits, and local soft tissue invasion.

Because of the indolent nature of low-grade and intermediate-grade tumors, surgical resection of the primary site with negative margins may be considered sufficient. Overall, survival at 5 years approaches 80% to 90%. In contrast, high-grade histology in mucoepidermoid carcinoma is an independent factor predictive of poor overall survival (40%–50% at 5 years), and for increased risk for locoregional failure and distant metastases. Recommended therapy for tumors with high-grade histology includes surgical resection with adjuvant radiation therapy. In patients with high-grade histology, elective nodal dissection may be considered at the time of primary surgical intervention. However, information about histologic grade of the tumor is seldom available preoperatively.

Other factors associated with poor outcome include advanced T stage, clinically evident nodal metastases, and identification of distant metastases at presentation. Presence of perineural invasion implies high-grade histology and associated poor outcomes ( Fig. 1 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree