Fig. 5.1

Continuum of translational research (Khoury et al. 2010; Glasgow et al. 2012) T0 scientific discovery research, T1 translational research from discovery to candidate application, T2 translational research from candidate application to evidence-based recommendation or policy, T3 translational research from recommendation to practice and control programs, T4 translational research from practice to population health impact (Modified from Khoury et al. (2010))

5.4.2 Challenges to Conducting Research in SSA

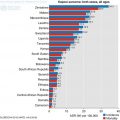

Effective health research has four pre-requisites: individual research skills and abilities, appropriate infrastructure, relevance to national policies, and the ability to contribute to global research and policy needs (Trostle 1992; Chu et al. 2014). Despite the repository or natural resources, intellectual capital, and indigenous knowledge and culture, SSAn are nevertheless limited in their research capacity due to several reasons. Most of these reasons can be grouped into one of three categories: funding, logistical, and ethical barriers (Runyon et al. 2013). Lack of time and funding have been described as the most significant barriers to conducting cancer care research, and this is especially true in most countries in SSA where physician salaries are generally smaller and patient loads higher than in high-income countries. Moreover, obtaining grant funding for projects in developing countries can be far more difficult than obtaining funding for similar projects in developed countries. Hence only 10% of global research funding goes to diseases which comprise 90% of the global burden (Ad Hoc Committee on Health Research 1996) (Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.2

UNESCO science citation index 2010 for Sub-Saharan Africa. Scientific publications in sub-Saharan Africa, 2000–2008. For those countries that produced more than 100 publications in 2008. Top 7 countries shown in the top graph and next 10 countries in the bottom graph

Some of the international funding agencies have recognized the funding gap in resource sparse countries and have begun to make some opportunities available which can only be applied for by or in collaboration with researchers from LMIC. A good example is funding opportunities through the National Cancer Institute RFA-CA-15-024 Cancer Detection, Diagnosis, and Treatment Technologies for Global Health, the UG3/UH3 mechanism and the Emerging Global Leader Award, K43 mechanism. Despite these welcome emerging opportunities, they remain small and relatively short term for the burden of cancer in SSA.

In addition to funding barriers, most countries in SSA have significant logistic challenges to research. This includes lack of well-equipped laboratories and other physical infrastructure, including electricity, water, quiet areas for informed consent, computers, printers, copiers, Internet access, telephones and airtime (Runyon et al. 2013; Tinto et al. 2013). The busy and chaotic work settings of clinics and hospitals in most of SSA also makes research challenging. On top of this is poor record keeping system and a lack of data or tissue banks. All these make it difficult to call up information when necessary.

Lack of an established research infrastructure, including institutional review boards, dedicated research administrative staff, and research mentors, can be another important challenge (Adewole et al. 2014). Worse still is the lack of expertise in preparing manuscripts for publication. Because of a lack of research infrastructure, the research agenda is often imposed by researchers from HIC.

Understanding these challenges is integral to designing a high-quality research study in SSA. To be successful, the initial clinical or translational research plan should take into account the local burden of disease and the barriers to conducting research in resource-limited settings.

5.5 Way Forward

A lot needs to be done to improve the opportunity for more primary, translational and clinical trials in SSA. In the first place, it is necessary to invest in the rebranding and repositioning of the universities and research centres in SSA to enable researchers and scientists that work in these institutions engage in world-class research without having to emigrate. Developing and utilizing these existing institutions is the only way by which sustainability can be guaranteed. While not giving excuses to the home government in each country, it may be difficult for them to achieve this without the support of international partners such as International Funding bodies, Non-Governmental Organizations, Centres of Excellence in respective fields.

One way to achieve the repositioning of the research centres is through formation of partnerships and networks. Such partnerships carry the potential in building sustainable cancer research programmes while fostering improvements in multidisciplinary cancer care in SSA (Adewole et al. 2014; Elzawawy 2015). The level of partnership can be by North to South, South to South collaboration or Public private partnership. In North to south collaboration, colleagues from high income institutions bring expertise, funding, and resources to SSA for the purpose of research. Incorporated in this programme is a structured educational programme to build the research workforce in SSA. Technology transfer should be integrated into these educational training programs.

In the long term, the process of twinning occurs between the HIC health care institutions or medical schools with counterparts in Africa and other LMIC (Tinto et al. 2013; Pallangyo et al. 2012). HIC collaborators may develop structured mentorship programs with African counterparts between the twinned institutions. This collaboration should also provide their African counterparts with access to distant learning resources such as online libraries, protocol development, statistical expertise, database development, and management. While integrating new avenues in cancer treatment and diagnosis is important, modern approaches in descriptive, analytical and molecular epidemiology should also be prioritized in Africa to provide the evidence-base for the establishment of relevant and effective public health policies to prevent cancer. In terms of causes and prevention of cancer, interdisciplinary approaches linking the basic sciences to both the clinical treatment and management of cancer but also to epidemiology and public health should be a priority (Adewole et al. 2014).

A good example of successful and mutually beneficial North to South collaboration is between Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), United States and Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria. This initiative which was first nicknamed ‘African Colorectal Cancer Group (ACCG)’ when it started in 2010, has recently been expanded to African Research Group in Oncology (ARGO). The process has led to initiation of two large cooperative researches, development of a matched tissue bank, training of many surgical oncologists and pathologists in Nigeria, development of research infrastructure at OAU which can be utilized by all researchers in SSA and organization of three large cancer symposia where hundreds of interested local faculties were trained. MSKCC has benefited from this initiative as their faculty staffs have unique opportunity to learn about global oncology and the dynamics involved in the management of cancer in LMIC.

Other examples include the Swiss Tropical Institute and the Ifakara Center of the Tanzanian National Institute of Medical Research; (Edejer 1999) University of Ibadan and the University of Chicago international partnership for Interdisciplinary Research Training in Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Disorders Across the Lifespan; the African Breast Cancer Study (NBCS) which is a collaboration between University of Chicago and many academic centres in Nigeria, Uganda and Cameroon. More recently is the collaboration between the College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Nigeria and the Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom. All these collaborations have shown significant benefit to both parties.

For successful North to South collaboration, the following principles must be adhered to. This includes both teams deciding on the objectives together; building up mutual trust; sharing information, and developing networks using the relative advantages of each partner. It is important that they share responsibility equally based on the capability of the team; create transparency on all issue including publication; monitor and evaluate the collaboration regularly; disseminate the results of the research widely; be the first to implement the results of their finding; share the profits equitably; increase research capacity in less developed centers; and build on achievements (Edejer 1999).

In addition, South to South collaborations which entails leveraging on the research skills of countries within SSA are possible. These regional partnerships should focus on providing technical support and research skills for local faculties. Other types of support might include the provision of information and communication technologies, helping with obtaining local funds or international grants, instructions on how to collaborate on international work in their own countries, suggestions for ways to provide help and training in managing the financial and secretarial (administrative) aspects of a research project, helping with defining ethical considerations in research, and providing assistance with editing of manuscripts intended for international publications (Chu et al. 2014). The Training Health Researchers into Vocational Excellence in East Africa (THRiVE) initiative is another successful South to South collaboration which aims to improve regional research capacity by linking academic institutions from Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Kenya. Also several British universities provide financial and technical support (Chu et al. 2014).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree