Carcinoma of unknown primary origin (CUPO) is estimated to represent between 3% and 5% of all head and neck cancer presentations, and can pose a challenge in assessment when diagnosed.1 Metastatic carcinoma from an occult upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) source carries a different prognosis than cancers metastatic to the neck from an infraclavicular source. When patients have a primary site identified, they benefit from the ability to offer site-specific therapy that can reduce the morbidity of treatment. Identification of a primary site also improves the capacity for prognostic counseling while facilitating the long-term assessment for recurrence. With advances in diagnostic imaging, development of new surgical techniques, and the expansion of immunohistochemical (IHC) and gene expression studies for tissue specimens, the assessment of CUPO patients continues to evolve.

The majority of patients initially considered to have a CUPO, in particular when seen with isolated lymphadenopathy of level II/III of the neck, are ultimately diagnosed with a squamous cell carcinoma of UADT.1 Additional sources for CUPO in the head and neck (beyond mucosal-based UADT sources) include skin cancers, lung, breast, ovary, testicular, esophageal/gastric, colon, salivary gland, and thyroid cancer. Metastases to the lower neck (level IV/low level V) are typically from an infraclavicular source and are frequently adenocarcinomas. Greater than 50% of CUPO primary sites, undetected by initial routine clinical examination, are identified after tissue biopsy and radiologic examination.1

Overall, CUPO presentations in the head and neck can be broadly categorized into two groups based on prognosis:

“Unfavorable prognosis”—metastatic adenocarcinoma to the bone, brain, and/or viscera

“Favorable prognosis”—germ-cell tumors, adenocarcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck metastatic to a lymph node

For patients diagnosed with CUPO that fall within the first category, median survival ranges between 7 and 11 months. For individuals in latter group, prognosis typically aligns with the biologic behavior of the tumor at the associated primary site. This chapter will focus on them.1

Once a fine needle aspiration (FNA) or open biopsy of a neck mass establishes the diagnosis of a malignancy without an identified primary site, a structured CUPO evaluation should occur. The pathology from the lymph node can provide guidance for the subsequent assessment. Undifferentiated carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma can be viewed differently for potential primary sites; however the assessment approach is similar for all of these pathologies. IHC studies on FNA specimens from the neck can also provide guidance for endoscopy and biopsy, but are not a substitute for a systematic assessment.

Individuals with a history of a prior cancer (e.g., lung, breast, colon, stomach, hematologic, cutaneous) should undergo assessments that include an evaluation for possible recurrence and distant spread of these cancers to the head and neck. The patient history should take into account any unique risk factors. Patients with a significant history of sun exposure require a detailed examination for tumors of dermatologic origin. Individuals from Southeast Asia, in particular the Cantonese regions of China, should be viewed as having an increased risk for nasopharyngeal carcinoma and should undergo endoscopic examination and biopsy of this region (with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) testing of tissue specimens) as part of their assessment.

Symptom assessment should include a review for complaints that may be suggestive of a potential primary site location such as:

UADT—dysphagia, odynophagia, otalgia, throat pain, dyspnea/cough, hoarseness, dysarthria

Lower aerodigestive tract—melena, hematemesis, hemoptysis, back pain, gastrointestinal irregularities

Additional symptoms of concern—hematuria, new onset gynecologic/prostate symptoms, night sweats/fevers, unexplained weight loss, change in tolerated diet

Reviewing the patient’s social history, detailing prior tobacco and alcohol use, and reviewing occupational exposures, can also be helpful in evaluating the risk for particular cancers.

A detailed head and neck examination is critical to the appropriate assessment of the CUPO patient. Examination for a mucosal-based UADT primary should include inspection of the oral cavity, oropharynx, nasal cavity, nasopharynx, larynx (including supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis), and hypopharynx surface anatomy and subsites. Bimanual exam of the tongue and floor of mouth can reveal submucosal tumors in this region, and may reveal masses of the sublingual and submandibular glands not readily noted on neck exam. Nasal endoscopy, indirect mirror exam, and flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy allow for visual examination of the nasopharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx. Asymmetry, ulceration, or pooling of secretions, and fullness of an anatomic subsite should provoke review of the site at the time of imaging and serve as a site for potential biopsy at the time of operative evaluation.

Carcinoma of unknown primary origin in the head and neck requires consideration for potential cutaneous sites of origin and should include careful examination of the scalp, external ear and auditory canal, and face for potential primary lesions.

The location of the involved lymph node can help provide clues for the potential primary site of origin. Level I nodes are most consistent with regional spread of disease from the oral cavity, lips, and cutaneous chin. Upper level II lymph nodes are more likely from tumors of the oral cavity, oropharynx, supraglottis, and nasopharynx. Upper level V nodes suggest a primary cancer in the nasopharynx. An isolated level III node is more likely to reflect an oropharyngeal, supraglottic, thyroid, or hypopharyngeal primary tumor. Lower level IV and level V nodes can indicate an infraclavicular source.

As with the assessment of any head and neck cancer, imaging plays a critical role in evaluation, yet should be tailored to optimize efficient use of resources.

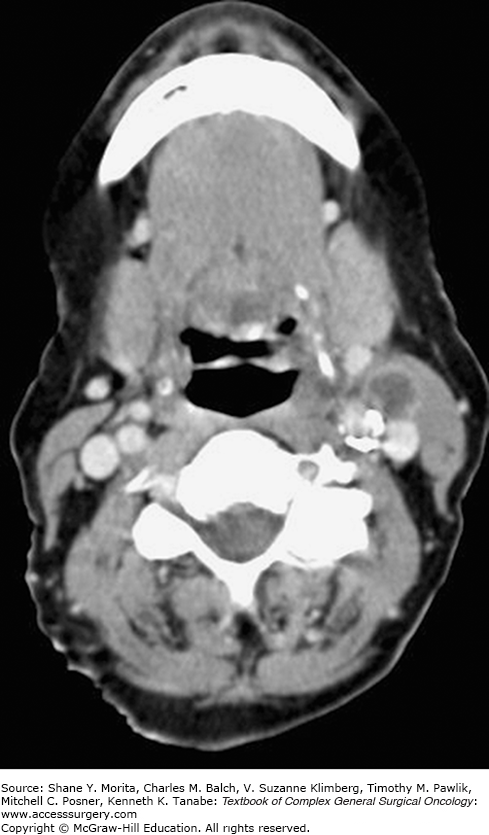

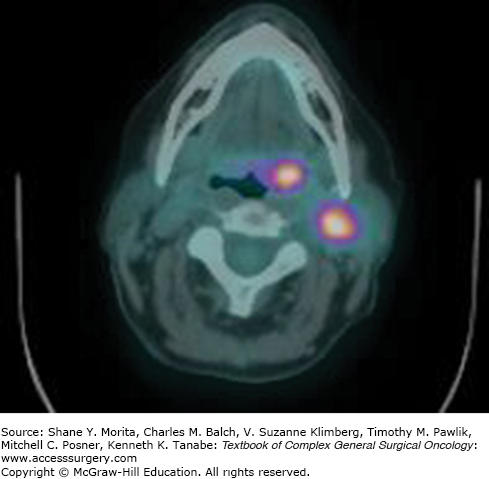

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines advocate chest imaging, CT with contrast or MRI with gadolinium (from skull base to thoracic inlet), and PET/CT (before biopsy) for the initial diagnostic evaluation of CUPO of the head and neck. (Figs. 53-1 and 53-2 demonstrate a patient with left neck lymphadenopathy notable on CT scan while the primary site is more clearly demonstrated through PET/CT imaging.) The NCCN guidelines also suggest abdominal/pelvic CT imaging for individuals presenting primarily with supraclavicular level V or level IV lymphadenopathy.2

Miller et al reported on a series of 31 patients who underwent a standard assessment that included CT and/or MRI, and subsequent PET imaging if the primary site remained undetected. PET imaging detected a primary site in nine patients. In another five patients, whose PET imaging was negative, primary sites were detected with panendoscopy (two tongue base, three tonsil). The combination of PET and panendoscopy ultimately led to the detection of a primary site in 45% of patients. In the patients who retained the diagnosis of CUPO, only one patient (less than 6% of study population) subsequently manifested a primary site with local progression after treatment.3

When reviewing the literature, the reader should be aware that PET imaging is not the same as PET/CT and some of the earlier experiences with this technology report the experience of PET alone in the assessment of these patients. A list of these reported detection rates, sensitivity, and specificity in the setting of CUPO are displayed in Table 53-1.

Zhu et al reviewed the results of seven studies, including 246 patients, to assess the efficacy of PET/CT in the detection of a primary site in CUPO patients. The sensitivity and specificity of PET/CT were 0.97 and 0.68, respectively. The detection rate was 0.44. The authors concluded that PET/CT possesses a high sensitivity and low specificity in the detection of a primary site in patients with the diagnosis of CUPO.4 In another series, the identification of the primary site in CUPO patients rose from 25% (with standard approach of clinic and OR assessment) to 55% with the adoption of PET/CT.5

Pattani et al reported on a series of patients with CUPO where PET/CT localized the primary site in 52% that were subsequently confirmed with operative biopsy. Empiric panendoscopy and biopsy identified a primary site in only one patient who was considered to be PET/CT-negative. With an increasing focus on cost containment, the authors expressed concern about the empiric use of panendoscopy with biopsy in the setting of a negative PET/CT, since it had revealed less than 10% of primary sites in their series.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree