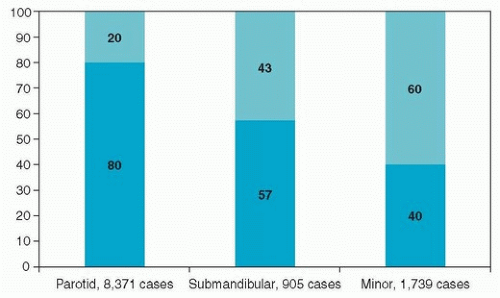

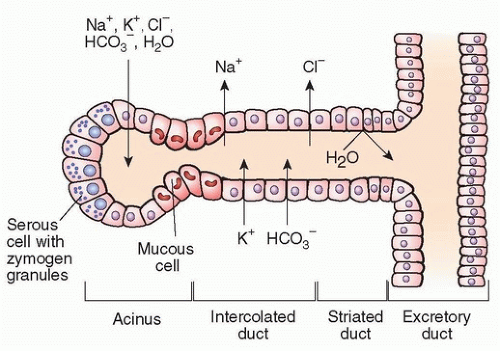

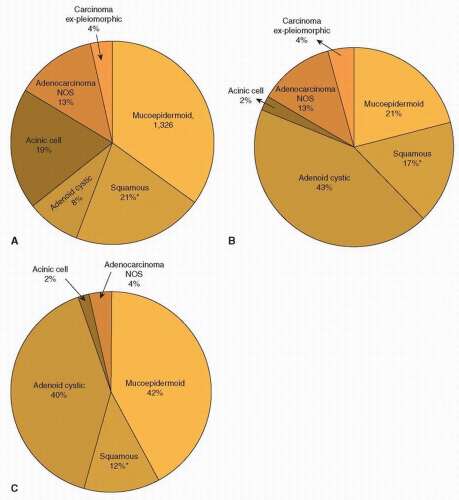

There are two types of salivary glands; the major salivary glands, which are readily identifiable, with anatomically distinct excretory ducts, and the minor salivary glands, which are less easily identifiable, smaller, and lack distinct ducts. The parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands are the major salivary glands, whereas the minor salivary glands are not individually named and are found throughout the length of the upper aerodigestive tract.

Parotid Gland

The paired parotid glands are the largest of the major salivary glands and form the lateral portions of the facial contour. The parotid gland is bounded by the cartilage of the external auditory canal posteriorly, the mandibular ramus and the masseter muscle medially, and the buccinator muscle anteriorly. The superior border is the zygoma, whereas the inferior aspect, also known as the “tail,” lies over the posterior belly of the digastric muscle medially and sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle laterally. The medial portion of the parotid gland abuts and sometimes extends into the parapharyngeal space

(Fig. 21.1). Accessory parotid tissue may be found anterior to the body of the gland, along the course of Stensen duct, in 21% of the population.

1 The gland is encased by a capsule derived from the deep cervical fascia and is further enveloped by the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) in the face and the platysma in the neck. The parotid (Stensen) duct travels along the surface of the masseter and turns medial at its anterior border, transversing the buccal adipose tissue pad and the buccinator, and opens into the oral cavity opposite the second maxillary molar.

The arterial supply of the parotid gland comes from the two terminal branches of the external carotid artery: the superficial temporal and internal maxillary arteries. The venous outflow is collected by the respective superficial temporal and internal maxillary veins, which then join to form the retromandibular vein. The anterior division of the retromandibular vein along with the anterior facial vein forms the common facial vein. The posterior division joins the posterior auricular vein to drain into the external jugular vein.

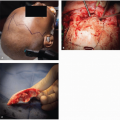

There are as many as 20 lymph nodes within and adjacent to the capsule of the parotid gland, and these nodes are the first echelon of nodes to receive lymphatic drainage from the soft tissues of the temporal scalp, cheek, ear, and external auditory canal. Hence, the parotid lymph nodes may harbor metastatic foci from cancers that arise from these sites. Efferent parotid lymphatics drain into the lymph nodes of the superior and middle deep jugular chain.

Another important anatomic structure that must be considered in the management of parotid tumors is the facial nerve, which runs through the gland and serves as a landmark that separates the parotid into superficial and deep lobes. The main trunk of the facial nerve exits the stylomastoid foramen and enters the parenchyma of the parotid gland, where it typically divides into an upper and lower division. It then further subdivides into its five principal branches, but the arborization of the nerve can be quite varied.

2 The point at which the main trunk of the facial nerve divides for the first time is referred to as the pes anserinus. The lower division contains the branches to the platysma (cervical branch) and the lower lip depressors (marginal mandibular branch). The marginal mandibular nerve is located deep to the platysma muscle and lateral to the facial vein and the capsule of the submandibular gland. The midface division (zygomaticobuccal branches) supplies innervation to the buccal, zygomatic, and lower eyelid muscle groups. The buccal branch is identified in the vicinity of the parotid (Stensen) salivary duct. The upper face division (frontal branch) travels lateral to the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia to supply the frontalis and superior orbicularis oculi muscles.

Other nerves of importance encountered during parotid gland surgery are the greater auricular and auriculotemporal nerves. The greater auricular nerve is found on the lateral surface of SCM muscle, along the lateral border of the parotid gland. Its anterior and posterior branches provide sensation to the inferior aspect of the auricle and periauricular skin. The auriculotemporal nerve is a branch of the fifth cranial nerve (trigeminal nerve), which travels along with the superficial temporal vessels, posterior to the parotid, providing sensation to the temporal region. The auriculotemporal nerve also provides parasympathetic innervation to the parotid gland from the otic ganglion. After resection of the parotid salivary tissues, these fibers may form an aberrant innervation with sweat glands leading to perspiration in response to the gustatory stimuli, a phenomenon known as gustatory sweating (Frey syndrome).

Submandibular Gland

The paired submandibular glands are located in the superior aspect of the anterior neck, bounded superiorly and laterally by the body of the mandible. The platysma muscle covers the gland’s lateral border, and the hyoglossus muscle lies medial to the gland. The gland resides posterior to the lateral border of the mylohyoid muscle. The submandibular (Wharton) duct originates from the multiple smaller branches originating from the medial aspect of the gland. It courses anteriorly and superiorly first between the mylohyoid and the hyoglossus muscles and then between the sublingual gland and the genioglossus muscle. The duct is situated between the lingual and hypoglossal nerves while on the surface of the hyoglossus, but at the anterior border of the muscle, the branches of the lingual nerve cross the duct to assume a more medial position. The submandibular duct travels

a total distance of ˜5 cm and empties into the anterior floor of the mouth.

The facial artery provides the main blood supply to the submandibular gland. This artery courses deep to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and travels either along the medial aspect of the gland or through the gland parenchyma and traverses the lower border of the mandible at the antegonial notch curving over the insertion of the masseter muscle into the anterior border of the mandible. Venous drainage is supplied by the anterior facial vein.

Although there is no lymphoid tissue within the parenchyma of the submandibular gland, there are a number of pre- and postvascular lymph nodes adjacent to the facial vessels, which run over the lateral aspect of the gland, which serve as the first echelon nodes for lymphatic drainage from the lip, oral cavity, and skin of the anterior face. These lymphatics can also drain into the deep jugular chain of nodes. Enlargement of the submandibular nodes can be difficult to distinguish from a primary tumor of the submandibular gland, and a metastatic process within these nodes may also invade the adjacent gland by direct extension.

Similar to the parotid, the submandibular gland lies in anatomical proximity to the facial nerve. The marginal mandibular branch runs along the inferior border of the mandible, just deep to the platysma muscle and lateral to the fascia of the gland. Additionally, the lingual and hypoglossal nerves are located deep to the medial surface of the gland, whereas the nerve to the mylohyoid is adjacent to the superior aspect of the gland

(Fig. 21.2).

Minor Salivary Glands

There are over 600 minor salivary glands distributed throughout the length of the upper aerodigestive tract, and approximately half of them are located on the hard palate. Tumors can arise in these glands in such diverse sites as the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, pharynx, nose, nasopharynx, and paranasal sinuses. Additionally, small rests of heterotopic salivary tissue can be located within the cervical lymph nodes, mandible, thyroid gland, and the middle ear.

3