45 Cancer of the Prostate

Epidemiology

Incidence, Etiology, and Genetics

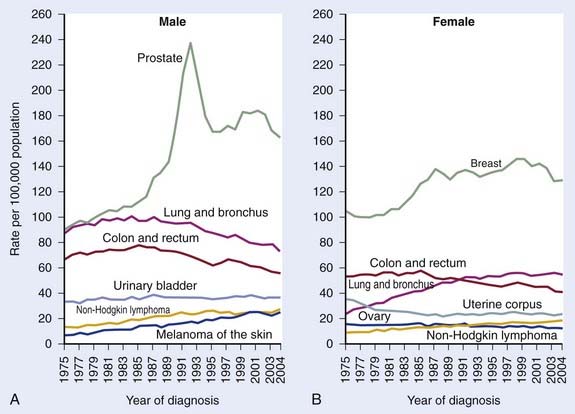

It was estimated that 186,320 men would be diagnosed as having prostate cancer in 2008.1 It is also estimated that approximately 28,660 men would die of prostate cancer, making prostate cancer the number two cause of cancer death in men.1 The annual age-adjusted cancer incidence lifetime risk of a man developing prostate cancer appeared to peak between 1991 and 1993, reflecting the initial “harvesting effect” from widespread screening in the early to mid 1990s (Fig. 45-1A,B). The role of serum testosterone levels in the development of prostate cancer remains controversial; however, one recent study suggests that higher levels of serum-free testosterone are associated with an increased risk of aggressive prostate cancer among older men.2 On the other hand, another recent study suggests that baseline serum testosterone levels have no prognostic significance in men treated with ADT and external-beam radiotherapy (EBRT).3

FIGURE 45-1 • A and B, Annual age-adjusted cancer incidence and death rates among males, US, prostate cancer by year.1

Early trials conducted in Canada and Europe supported PSA screening and early treatment, but two recently completed large prospective trials reached conflicting conclusions.4–10 The American Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovarian Cancer screening trial included nearly 77,000 men, but at least 52% of the men on the control arm (“not screened”) got screened such that the relative risk of being treated was only 17% higher in the screened arm. Not surprisingly with short follow-up this was a negative study. In contrast, the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer included 182,000 men with a likelihood of being treated for prostate cancer 70% higher in the screened group. Not surprisingly, with far less screening in the control group they noted a 20% reduction in death from prostate cancer (P = 0.04).

Prostate cancer is generally considered a disease of “older men,” with an average age of 70 years at diagnosis. With routine screening, the number of men diagnosed at younger than 60 years of age will increase. There are wide variations in the incidence of prostate cancer internationally, with men from Scandinavian countries experiencing the highest rates and men from Asia the lowest. The highest incidence of prostate cancer in the United States is in black men (the ratio of blacks/ whites is 1.5-2.0 : 1). Diet, obesity, or environmental exposures related to urban living may account for a portion of the predisposition noted among black men. Black men also tend to present at an earlier age and with more advanced disease.11 Biological differences have been proposed by some investigators; however, socioeconomic and lifestyle factors are a more likely basis for this phenomenon. It appears to be reasonably well-established that the incidence of cytosine adenine glutamine (CAG) repeats is higher in black men.12 However, variations in polymorphisms in different populations are expected and alone are not proof of a cause-and-effect relationship.13 Most studies based on data from prospective randomized trials fail to identify race as an independent prognostic factor and therapy should not be modified based on race alone.11,13

A genetic predisposition may profoundly affect the risk of developing prostate cancer but a detailed description of this topic is beyond the scope of this chapter and can be found elsewhere.14 Recent studies have identified a number of genes that seem to correlate with susceptibility for prostate cancer in different populations. For example, single-nucleotide polymorphism–based, genome-wide linkage scans performed on 131 white families with a history of prostate cancer found the strongest evidence for linkage at 16q23 (LOD = 2.70). Prostate cancer linkage to the same region of 16q23 has been observed by others, but was not detected in other prior linkage studies.15 Genome-wide linkage analysis performed on another large prostate cancer pedigree from a population of cases and first-degree relatives identified a 14 Mb haplotype on chromosome 5 (5p13-q12). Two polymorphisms were associated with prostate cancer risk: rs3212649 (odds ratio [OR] = 1.67 [1.07-2.6], P = 0.0009) and rs1126643 (OR = 1.52 [1.01-2.28], P = 0.0088) with an association in both familial and sporadic prostate cancer.16 Screening first-degree relatives of prostate cancer patients may improve the cost-effectiveness of this practice. Thus the precise cause of prostate cancer is unknown, but it is likely to be multifactorial.

Prostate cancer does not appear to be related to benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH); however, BPH increases the risk of a high PSA, which may lead incidentally to a diagnosis of disease.17 Vasectomy does not appear to be a risk factor.18–20 The number of sexual partners, venereal disease, dietary fat, alcohol, cadmium, and exercise have inconsistently been supported by studies as risk factors.21–26 Consumption of high doses of multivitamins and supplements is associated with an increased risk of advanced and fatal prostate cancer.27 Early epidemiologic and in vitro studies suggest a possible role of vitamin D and calcium, but larger and more recent studies do not.28–31 Early studies also suggested that a high intake of vitamin E was associated with a lower incidence of prostate cancer in one prospective randomized trial, but more recent large prospective studies have shown that vitamin E does not protect against prostate cancer, but increased consumption of gamma-tocopherol is associated with a reduced risk of clinically relevant disease.32–37 Another small study suggests that pomegranate juice may have a modest effect on PSA in patients failing therapy.38 Several studies suggest that smoking may be associated with more extensive and aggressive disease cancer.39,40 In general, smoking appears to be at most weakly related to the risk factor of developing prostate cancer.41–45

Alcohol consumption has not been studied as extensively as might be thought, with early reports finding no association.22 Velicer and co-workers examined the association between alcohol use and prostate cancer among 34,565 men, in the Vitamins and Lifestyle cohort in Washington State.46 White wine consumption was associated with increased risk (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.27; confidence interval [CI] = 1.08-1.49), but red wine, liquor, and beer were not associated with prostate cancer. In the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, 3348 cases of prostate cancer were diagnosed among 45,433 eligible participants.47 No linear trend was observed between red wine consumption and prostate cancer in the full analytic cohort. Among men younger than 65 years of age with unchanged alcohol consumption in the prior 10 years, slightly lower risks were observed for men who consumed four or fewer glasses of red wine per week, whereas null or slight increased risks were observed for men who consumed more than four glasses per week, with a trend noted for an increase in the risk with moderate white wine consumption. Most recently a meta-analysis was performed to address this question. Despite many caveats in a recently completed meta-analysis, investigators concluded, “the alcohol-prostate cancer association remained significant despite controlling for the degree to which studies endeavored to eliminate false negatives from their control groups.”48 Clearly, more work is needed in this area.

Natural History

Many men may not benefit from treatment because the risk of death from early-stage, low-volume, low-grade disease has been estimated to be approximately 10% at 10 years, with conservative management and delayed hormonal therapy (HT) considered reasonable initial options for such men if their life expectancy is less than 10 years.49,50 However, local progression to bulky (T3) disease approaches 50% at 10 years, and beyond 10 years the risk of death seems to climb substantially.51 Historically, many men have been treated with HT alone because only recently has it become clear that HT alone is not as effective as HT combined with radiotherapy.52

Patients at a reduced risk for death from prostate cancer were those with T1a stage disease (10%), low grade (43%), and age of 70 or older.3 For patients with higher stage and grade disease, the need for treatment appears to be less controversial. Such patients have a higher risk of death and the benefits of therapy have now been well-established.6,53–58

Anatomy

External Anatomy

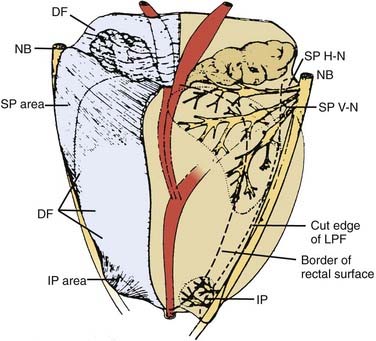

The normal prostate in a young man is walnut-sized (20 cc) and similar in consistency to the tip of the nose. The average gland in a patient of 65 years is approximately 40 cc. The prostate is penetrated by the urethra as the urethral canal, which then descends to the urogenital diaphragm and then to the bulb of the penis. The distal (apical) portion of the prostate rests against the urogenital diaphragm and the proximal (base) portion of the prostate rests against the bladder. The surface anatomy of the prostate is shown diagrammatically in Fig. 45-2.59 The prostate is surrounded by a complex array of fibroconnective tissue that is penetrated by bundles of nerves and vessels that run superior-laterally and inferior-laterally called the superior and inferior pedicles, which are attached to the pubic symphysis by puboprostatic ligaments.

FIGURE 45-2 • Distribution of nerve branches to prostate—right posterolateral view. Nerves within neurovascular bundle (NB) branch to supply prostate in large superior pedicle (SP) at prostate base and small inferior pedicle (IP) at prostate apex. Branches leave lateral pelvic fascia (LPF) to travel in Denonvilliers fascia (DF), which has been cut away from right half of prostate. Nerve branches from superior pedicle fan out over large pedicle area (thickened area of DF). Small horizontal subdivision (H-N) crosses base to midline; large vertical subdivision (V-N) fans out extensively over prostate surface as far distally as midprostate. Branches continue their course within prostate after penetrating capsule within large nerve penetration area (dotted line). Small inferior pedicle has limited ramification and nerve penetration area (dotted line).59

As the prostate narrows distally, the inferior pedicles course medially and it becomes more difficult to spare these nerves during a prostatectomy without increasing the risk of positive apical margins. Efforts to obtain wide margins in this region may result in a shortened external sphincter and a higher risk of incontinence. Up to 80% of patients have apical involvement, so it is not surprising that positive margins in this region following radical prostatectomy are not uncommon.60 Suboptimal surgical technique is the cause of positive apical margins in 50%, with the remaining cases attributed to extracapsular extension (ECE).61 True ECE is most common at the base in the rectolateral and superior pedicle, in association with regions that are penetrated by nerves (considered “routes of least resistance”).

Investigators from Johns Hopkins have argued that focal penetration with low-grade disease is of little clinical significance but “established extracapsular extension” (defined as a penetration of approximately 1 cm into surrounding fat) is a major unfavorable prognostic factor if the tumor Gleason score (GS) is grade 7 or higher.62 It is unclear whether their generalizations hold true for patients with unfavorable pretreatment characteristics for whom less rigorous histopathologic evaluations are conducted. Data from the Mayo Clinic suggest patients with GSs of 7 or greater experience an increased risk of recurrences regardless of margin status.63,64

Internal Anatomy

The distribution of cancer does not appear to be random, with adenocarcinoma involving the first 5 to 8 mm of the apical portion of the gland in up to 80% and multifocal in up to 85% of patients. Even among the earliest cases, with mean volumes of only 0.11 ml, 40% are multifocal65 Historically, perineural invasion (PNI) was a common finding seen in up to 84% of patients. Because of stage migration and a higher incidence of pathologically confined disease, this incidence of PNI may be decreasing.66 In a study of men with T2 disease, ECE within perineural spaces was noted in 50% and in the remaining cases it occurred with PNI.59 This fact is in part responsible for discouraging the use of nerve sparing in patients with adverse pretreatment features.

Pathologic Considerations

Approximately 95% of all prostate cancers are adenocarcinomas. Small cell anaplastic carcinomas with neuroendocrine features and lymphomas are best managed with chemotherapy with or without EBRT, whereas sarcomas and various other types of carcinomas are frequently managed by surgery with or without EBRT. Patients with these unusual histologic types tend to do poorly. Tumors displaying a signet-ring pattern, for example, represent an uncommon subtype with a 3-year survival of less than 20%.67

The most widely used histologic grading system was described by Gleason and colleagues.68 The Gleason pattern score, a sum of the two most common histologic patterns (“primary” and “secondary”), correlates with survival. The GS may range from 2 to 10, with contemporary series dividing patients into GS 6 or lower, GS of 7, and GS of 8 to 10.58,66,69 Patients with an unusually low GS (e.g., 4 or less) should have their slides re-reviewed by an expert pathologist. When this is done, some will have no cancer, but most will have higher-grade cancers.70 The presence of a tertiary pattern 5 significantly affects prognosis.71–74 Patients with a GS of 7 on biopsy and a tertiary pattern 5 are by convention upgraded to a GS of 8.

Fine-needle aspiration of the prostate is very specific (false-positive rate, 0%-2%), but not nearly as sensitive as once thought when six or fewer biopsies are taken.75,76 There has been a dramatic increase in the number of biopsies taken during the preceding 10 years. In the mid 1980s a single biopsy was usually taken based on a palpable abnormality. By the early to mid 1990s, random or “blind” biopsies were in response to an elevated PSA in addition to those areas with a palpable abnormality. Sextant biopsy became standard in the 1990s. By the late 1990s, it became clear that sextant biopsies were no longer adequate for patients with an elevated PSA.77,78 Obtaining at least two additional lateral cores substantially reduces that risk of missing foci of disease, whereas midline biopsies increase morbidity although rarely increasing the yield. In addition to reducing the number of false negative biopsies, obtaining six or more cores may provide prognostic information (see following discussion).79–81

The clinical significance of PNI remains controversial in part because pathologists do not uniformly comment on its presence or absence, intraprostatic versus extraprostatic PNI, nor the extent of involvement.82–88 The significance may also be different for patients treated by surgery and radiotherapy and may depend on the dose of radiation delivered.84,87,89,90 It appears that PNI correlates with more advanced pathologic stage, and worse outcomes with EBRT in the postoperative and definitive setting, but less so after brachytherapy.91–97 In a “borderline patient” (i.e., features straddling between low- and intermediate-risk disease) it may be prudent to consider PNI a “tie-breaker.”

Routes of Spread

Tumor volume, grade, and serum PSA are independent risk factors for ECE. The initial enthusiasm for PSA as a marker resulted from the belief that the serum PSA correlated with the tumor volume. Because of BPH, the correlation between PSA and tumor volume is poor for patients with PSAs less than 9 ng/ml, with the correlation driven by large cancers with serum PSAs greater than 22 ng/ml.17

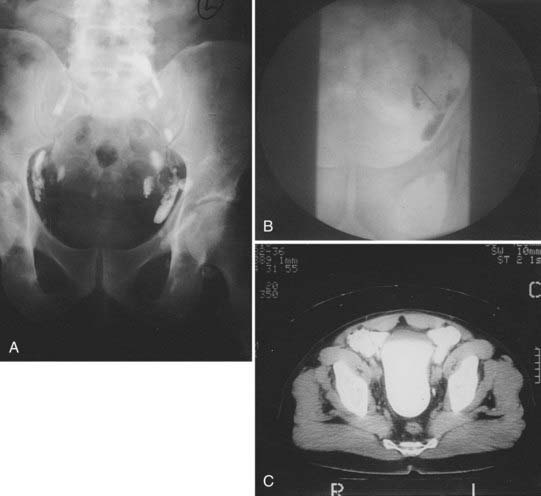

After local extension beyond the capsule of the prostate and seminal vesicles, tumor spreads to the pelvic lymph nodes.98 In addition to the classic involvement of the obturator nodes, high-risk patients frequently harbor metastasis to the external iliac, presacral, and presciatic nodes. Fig. 45-3 demonstrates by lymphangiography the location of the major nodal drainage areas. A more detailed discussion of the incidence of lymph node involvement by prostate cancer can be found in the subsection of “Clinical Presentation” later in this chapter.

Prognostic Factors

Prostate-Specific Antigen, Gleason Score, Stage, and Risk-Stratification Schemes

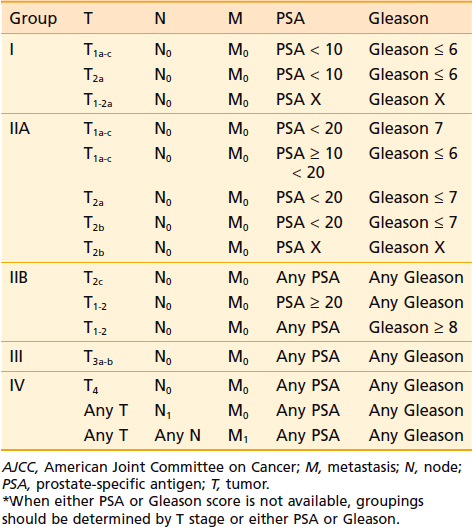

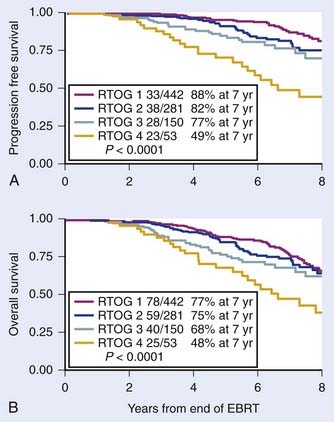

The major predictors of the extent of disease for men with localized prostate cancer are clinical stage, GS, pretreatment PSA, PNI, and the percentage of positive biopsies.91,92 Pretreatment PSA is the most important predictor of PSA failure, whereas GS, T stage, and age are the more important predictors of survival. Table 45-1 and Table 45-2 summarize the seventh edition of 2009 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system.99 This major revision includes PSA, finally acknowledging the effect of pretreatment PSA on survival (Fig. 45-4A,B) making it more useful in the clinic,100,101

FIGURE 45-4 • First study to demonstrate progression free survival (PFS) defined as death after PSA failure (A) and overall survival for patients treated with radiotherapy alone by pretreatment PSA (B), respectively.100

A large number of risk-stratification schemes and predictive algorithms have developed, and the number keeps growing.102 These predictive algorithms fall into four major categories: (1) simple additive models initially designed to predict PSA failure, (2) computational approaches initially designed to predict PSA failure, (3) computational approaches to predict pathologic endpoints, and (4) computational approaches to predict disease-specific and overall survival. There is overlap between these models because factors that predict PSA failure or pathologic stage tend to correlate with survival, with long-term follow-up.

The most commonly used risk stratification schemes defined “low risk” as a GS of 2 to 6, PSA less than 10 ng/ml, and stage T1c to T2a.103,104 So-called intermediate risk included patients with T2b, a GS of 7 or PSA of 10 to 20; and “high risk” as GS to 8 to 10, T2c or T3, or PSA greater than 20 ng/ml. The clinical significance of a GS of 7 is assumed to be equal to having a PSA between 10 and 20 ng/ml and that a GS of 8 is similar in importance to having a PSA greater than 20 ng/ml. Patients with two or more intermediate factors behaved more like a high-risk patient.105 Including the percentage of positive biopsies improves the predictive outcome for intermediate risk patients, but may depend on treatment type.79,106,107

Models using multivariate statistical approaches have been developed and some incorporated into the design of clinical trials.108–111 Nomograms developed using well-established statistical methods, based on relatively large number of patients, and validated by several institutions are available on the Internet. These nomograms are useful tools for providing estimates of expected outcomes for the average patient. However these nomograms should be used cautiously because the follow-up is limited, the data are not based on the results of prospective trials, and most of these nomograms don’t address survival. The Kattan nomogram for predicting the risk of metastasis has been shown to be useful for predicting cause-specific and overall survival in patients treated with EBRT.112

Nomograms have been described that predict the probability of pathologic endpoints, including the risk of ECE, seminal vesicle involvement (+SV) and lymph node involvement (+LN) based on pretreatment stage, PSA, and biopsy GS.66,113,114 Based on Partin’s original report, Roach described three relatively simple equations that allowed estimates to be made of the risk of ECE, +SV, and +LN without a calculator.115 The simplicity of these equations in part comes from the fact that each uses a very similar format, as shown in the following equations.

The equation used for estimating the risk of ECE is:

The equation used for estimating the risk of +SV is:

The equation used for estimating the risk of lymph node involvement is:

These equations are simple enough to memorize, they have been validated, and they have been shown to predict biochemical failure in patients undergoing EBRT and have been used for stratification in a large phase I and II three-dimensional (3-D) dose escalation trial (9406) and defined eligibility for a large phase III trial (9413) conducted by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG).116–120

Recently investigators have questioned the merits of the so-called Roach lymph node equation.121 They concluded that the Roach scores overestimated the actual rate of positive lymph nodes in contemporary patients. However, their series included men who underwent a node sampling or conventional node dissection, which may result in missing 40% or more of involved nodes when compared with an extended lymph node dissection.98,122,123 Their series also suffered from the fact that the average number of nodes examined was only five (two to nine), resulting in an observed incidence of lymph node involvement of only 3.3%. In contrast, in a cohort of patients with similar clinical features, Briganti and colleagues have shown that the likelihood of finding lymph node involvement is critically dependent on the number of lymph nodes taken.124 They showed that in a cohort of patients with the mean number of nodes examined of 15, the observed incidence of lymph node involvement noted was 10.2%. They also noted that the rate of lymph node involvement increased with the number of nodes removed 2 to 10 (5.6%), 10 to 14 (8.6%), 15 to 19 (10.2%), and 20 to 40 (17.6%) and on multivariate analysis the number of lymph nodes removed was a major predictor of finding lymph node involvement (P < 0.001). Briganti et al.124 concluded 28 nodes were required to yield a 90% ability to detect lymph node involvement and conversely that examining 10 nodes or fewer resulted in nearly a zero probably of finding lymph node involvement. It is also now clear that with more sensitive processing of nodal tissue or the application of molecular assays (such as reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction [RT-PCR], or determining PSA n–ribonucleic acid [n-RNA] copy number), lymph node involvement that would otherwise be missed can be identified.125–127

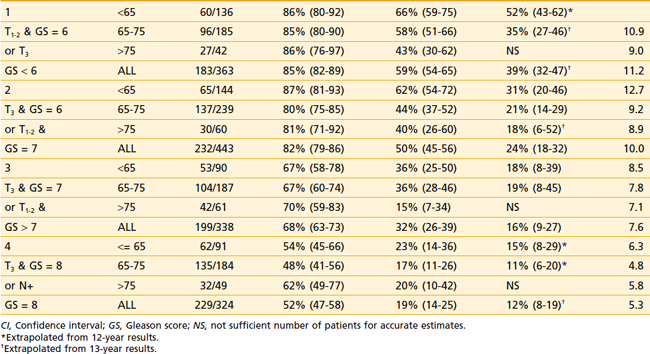

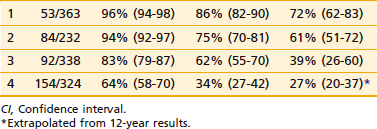

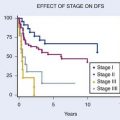

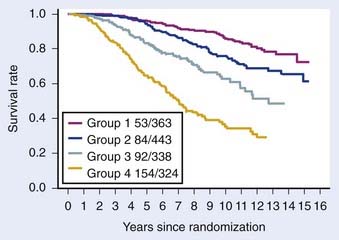

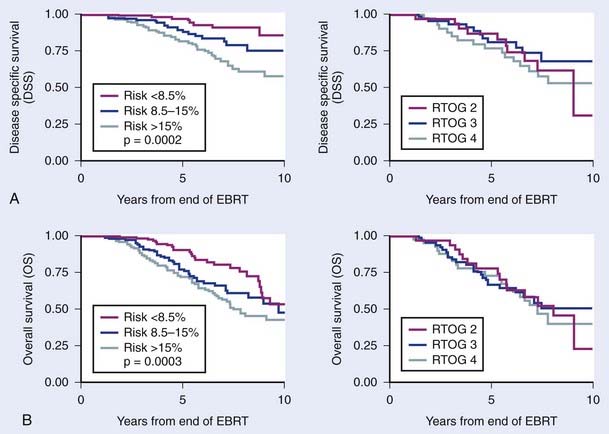

The first empirical model created to predict overall and disease-specific survival was described by investigators from the RTOG (Fig. 45-5); since then a number of others have been described (Table 45-3A,B).69,112 The Kattan nomogram for predicting the risk of metastasis appears to be a more robust model for predicting survival (Fig. 45-6).112

FIGURE 45-5 • Disease-specific survival, respectively, by four risk groups. From top to bottom: (1) group 1 patients had a GS = 2-6, and clinical stage T1-2Nx; (2) group 2 patients had a GS = 2-6, and T3Nx or N+ or GS = 7, T1-2Nx; (3) group 3 patients were clinically staged as T3Nx, with a GS = 7, or T1-2Nx, GS = 8-10; and (4) group 4 patients were clinically staged a T3Nx, S = 8-10, or N+, GS = 8-10.69

FIGURE 45-6 • Difference in freedom from biochemical failure, disease-specific survival, and overall survival among the three tertiles created by the nomogram using the cutoff points less than 8.5%, 8.5% to 15%, and greater than 15% (P < 0.001, 0.0002, and 0.0003, respectively). The risk of metastases using the categorized nomogram score (less than 8.5% and 8.5% to 15% versus greater than 15%), note preradiotherapy prostate specific antigen or Radiation Therapy Oncology Group risk (2 versus 3), was a significant predictor of disease-specific and overall survival for intermediate- and high-risk patients and intermediate- and high-risk patients with 15% or less risk for metastases.112

Predictive Markers for Prostate Cancer

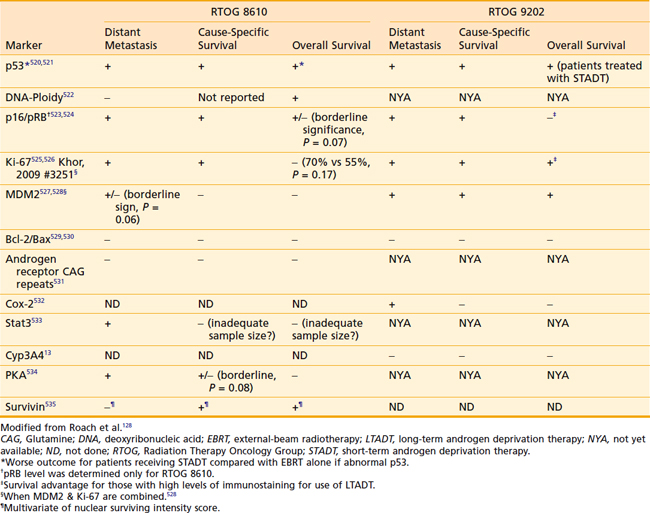

Increasingly, biomarkers are being added to predictive models in an effort to strengthen them but a detailed discussion of predictive markers is beyond the scope of this chapter. The RTOG has completed the largest number of studies to date including a wide range of markers using tissue from two phase III trials (RTOG 8610 and 9202). Preliminary assessments of p53, deoxyribonucleic acid ploidy, p16/pRB, Ki-67, MDM2, Bcl-2/Bax, CAG repeats, Cox-2, Stat3, Cyp3A4, and PKA have been completed and the findings are summarized in Table 45-4.128 Combining these markers with traditional pretreatment- and treatment-related variables may improve our ability to predict outcome and select the optimal treatment, but currently they do not appear to be ready for routine use.

Prostate-Specific Antigen, Lymphadenectomy, and Laparoscopic Nodal Sampling

There is no agreement on the indications for a lymphadenectomy or laparoscopic nodal sampling and there are widely disparate opinions as to the true incidence of lymph node involvement.121,129 Low-risk patients can be spared this procedure because they are very low-risk for lymph node involvement. High-risk patients who are found to have positive lymph nodes may benefit because of the potential benefits associated with early androgen deprivation.130,131 If a high-risk patient is going to undergo long-term androgen suppression and pelvic nodal irradiation, it may or may not be worth the cost and morbidity to undergo node sampling, particularly because of the false negative rate (see discussion later in this chapter).

The standard lymph node dissection is generally described as extending from the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels medially to the pelvic floor and to the inferior border of the prostate, and then superiorly along the hypogastric vessels back to the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels. If pelvic lymph nodes are negative, periaortic nodes are generally assumed to be negative, although skip metastases have been reported.132 There is a clear correlation between the side of palpable tumor and the side on which metastatic nodes are likely to be found.133 Frozen sections are highly specific (100%), but the sensitivity is modest at 65% or less.134 Although a standard lymph node dissection is usually considered a sensitive method of establishing lymph node status, it is far from 100% sensitive. In the series reported by Freeman and colleagues, 16% of patients who by standard approaches were defined as being pathologic stage T3N0 were found by a monoclonal epithelial PSA assay to have occult metastases.135 A more recent update of these data confirmed the highly important relevance of identifying occult positive nodes in approximately 13% of men with T3 disease.125 This estimate is likely to be an underestimation of the true incidence because not all of the nodes were sampled and occult nodal involvement may be more common than previously recognized.136 Some studies question the value of the extended node dissections but most confirm the problem of sampling errors and false negatives when limited sampling is done.137–139 Of note, however, studies including men undergoing extended dissections may underestimate the true incidence of metastatic disease, when assays thought to be more sensitive than a histopathologic evaluation are used.

The issue of occult nodal involvement was noted by Shariat et al.126 They compared the detection of human glandular kallikrein 2 (hK2) messenger RNA expression in archival lymph nodes and the risk of progression of disease and survival in patients who were found to have pathologically unfavorable but node-negative disease following prostatectomy.126 They evaluated total RNA extracted from fixed, paraffin-embedded, histopathologically normal pelvic lymph nodes from 199 pT3N0 prostate cancer patients for hK2-expressing cells using an RT-PCR/hK2 assay. RT-PCR/hK2 result was associated with disease progression (P = 0.001), distant metastases (P = 0.001), and cancer-specific survival (P = 0.005). These data suggest that the reported incidences of lymph node involvement in multiple surgical series must be taken with “a grain of salt” and provide a rationale for prophylactic pelvic nodal radiotherapy.66,140

The Significance of Lymph Node Involvement and Staging Studies

Ten-year survivors have been noted among patients with pathologically proven positive lymph nodes despite initial treatment with radiotherapy with and without HT, with the former generally doing substantially better than the latter group.58,69,141,142 Thus, there may be a subpopulation of patients with nodal disease that is controllable.140,143–145 Routine chest x-ray studies and cystoscopic examinations are unwarranted unless accompanied by the presence of a smoking history or urinary symptoms. Bone scans are not justified if the PSA is less than or equal to 10 ng/ml with a relatively poor yield for this test until the PSA exceeds 50 ng/ml when the serum alkaline phosphatase is normal or if the GS 7 or less. Routine lymphangiography has no role in the staging of prostate cancer. Neither abdominal-pelvic computed tomography (CT) nor conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appears to be warranted if the PSA is less than 20 ng/ml.146,147 These scans may be of limited value in this setting because of the poor correlation between the size of lymph nodes and the presence of cancer.148

Pelvic nodal disease can also be evaluated by using an MRI-compatible, nanoparticle-based imaging agent such as dextran-coated ferrous material (see discussion on whole-pelvic radiotherapy [WPRT] later in this chapter).149 Although the findings from this study were quite impressive, the United States Food and Drug Administration declined to give clearance to the use of this agent and as a result it was available only in Europe.150 The use of sentinel-node imaging techniques is also a promising strategy for identifying areas at risk to undergo lymph node radiotherapy.151,152 In a study of 25 patients, Ganswindt et al.151 concluded that using a standard CT-based planning target volume, relevant sentinel lymph nodes would have been missed in 19 of 25 patients (76%), mostly involving the presacral and perirectal nodes.

Endorectal MRI combined with magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) may prove to be useful in staging and treatment planning for selected patients, but its use is not routinely supported by American College of Radiology Guidelines.153–156 In a study of 62 patients undergoing radical prostatectomy followed by an evaluation of histopathologic step-sections, they reported that the addition of MRSI (high specificity) to MRI (high sensitivity) resulted in improved localization of prostate cancer within the prostate. When both MRI and MRSI were positive, they reported a specificity of up to 91% (P < 0.05 versus MRI alone). MRSI may also improve the accuracy of cancer detection by MRI in patients with postbiopsy hemorrhage. An improvement in sensitivity and specificity of cancer localization can be attained when MRI and MRSI data are combined with biopsy data.157 MRSI might provide new insights into tumor aggressiveness, leading to an improvement in risk assessment in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer.158

Definitions of Failure Following Definitive Local Therapies

Definitions of Failure Following Radiation Therapy

Post-treatment biopsies have been used to assess local tumor eradication with a much higher incidence of residual tumor noted than suggested by palpation alone. The identification of histologically viable tumor after more than 3 years is usually reflective of persistent disease. A wide range of results in the incidence of positive biopsies following radiotherapy can be found in the literature. These differences reflect patient selection bias, differences in the effectiveness of treatment, and the PSA level at the time of biopsy. If patients with locally advanced disease or with palpable regrowth are biopsied, the positive biopsy rate approaches 90%. If patients with low PSAs, clinically controlled disease, and nonrising PSAs are biopsied, the positive biopsy rate is much lower.159–161 Routine post-treatment biopsies are hampered by the reluctance of patients to undergo this invasive procedure for which a certain course of action is lacking. Cost and ambiguity in interpretation of biopsies are also problematic. Pathologic interpretations may include “persistent disease with treatment effect” versus “persistent disease without treatment effect,” with the latter being considered “positive” and the former “equivocal” or “negative.”

Studies involving cohorts of consecutive patients undergoing post-treatment biopsies following conventional EBRT are instructive but post-treatment biopsies are not considered the gold standard after radiotherapy.160 Some studies support a relationship between the dose of radiation delivered and the risk of a positive biopsy, although others do not, leaving this issue unresolved. These conflicting results may reflect problems with sample size, duration of follow-up, differences in patient selection, the number of biopsies obtained, and the use of ADT (ADT reduces the risk of positive biopsies).

The use of the serum PSA has improved our ability to identify treatment failure much earlier. Eradication of local tumor results in a substantial decline (>90% reduction) in the serum PSA. An empirical “rule of thumb” is that the PSA half-life following EBRT is approximately 3 months. The lowest PSA value achieved following EBRT is typically reached at 24 to 36 months but continued declines may be seen at 4 to 5 years and beyond. The rate of decline following brachytherapy tends to be more variable, but the median nadir tends to be lower and to occur later.162

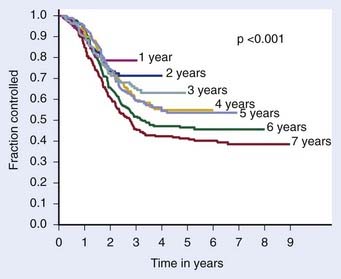

The definition of biochemical (PSA) failure following radiotherapy has evolved during the preceding 10 years, with the definition having a substantial effect on the percentage of patients considered free of disease. The first Consensus Conference sponsored by the American Society of Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO) defined failure based on three consecutive rises in the PSA.163 However, the ASTRO Consensus definition did not specify how much of a rise was significant.164 Because of random variations, occasionally three consecutive rises may occur by chance alone. It is well-known that the PSA tends to increase normally with age, so very small increases separated over a long period might not represent progression. The ASTRO definition also fails to specify whether the lowest value ever achieved should be used to define the nadir or whether the lowest value prior to rising should be used. The ASTRO definition also did not address how tied values (e.g., 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.3, 0.7, and 0.9 ng/ml) should be dealt with or the slope of the PSA curve. Using the ASTRO definition after brachytherapy was particularly problematic because “PSA blips” or benign bounces are known to occur in 20% of patients. There is also a bias against PSA control in patients treated with short-term ADT because the PSA may rise in response to the recovery of a patient serum testosterone in the absence of true biochemical failure.164 One of the most important shortcomings associated with the ASTRO definition is the importance of the duration of follow-up and effect of backdating on creating an artificial flattening of the PSA control curve.164 Several studies have shown that to obtain an accurate outcome using the ASTRO consensus definition requires long-term follow-up.165,166 Fig. 45-7 demonstrates how duration of follow-up affects the estimated control rate and suggests the median follow-up should exceed the estimated date of biochemical control at 2 years before estimates of control stablize.165 For example, if the median follow-up is 5 years, only estimates at 3 years or less are likely to be accurate.

The “Phoenix Definition” for Prostate-Specific Antigen Failure after Radiotherapy

As a result of the shortcomings of the first ASTRO definition described previously, a second Consensus Conference jointly sponsored by ASTRO and the RTOG was held in 2005 in Phoenix, Arizona.164 The expert panel recommended that biochemical failure be declared when the PSA rose by 2 ng/ml or more above the nadir PSA after the completion of EBRT with or without HT and that the date of failure be determined “at call” (not backdated). This definition was shown to have a higher sensitivity and specificity than the previous ASTRO definition and to correlate more closely to clinical failure. The authors of the consensus statement acknowledge that it may not be the most accurate definitive for “cure.” They also recommended that investigators continue to be allowed to use the 1996 ASTRO consensus definition after EBRT alone (no HT) with strict adherence to guidelines as to “adequate follow-up.” To avoid the artifacts resulting from short-term follow-up, they recommended that the reported date of control should be listed as 2 years short of the median follow-up. They argued that by retaining a (stricter) version of the ASTRO definition, investigators would retain the opportunity to compare their outcomes with those found in a vast existing body of literature. This definition should not be used after cryosurgery or HIFU or other modalities without validation with long-term follow-up and clinical data.

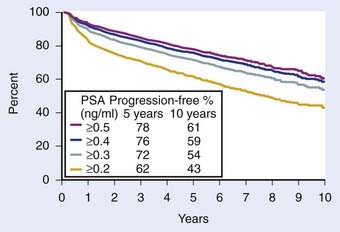

Definitions of Disease-Free Survival Following Surgery

The most appropriate definition for biochemical (PSA) failure following a radical prostatectomy is controversial. Some have defined a PSA failure as a PSA greater than 0.5 ng/ml, greater than 0.4 ng/ml, and greater than 0.3 ng/ml, although 0.2 ng/ml is the most commonly used threshold in the literature.167–169 Some argue that a PSA greater than 0.4 ng/ml should become the new standard170 (Fig. 45-8). Because many normal men have PSAs of 0.4 ng/ml with an intact prostate, it is not logical that such a high value can be considered to be consistent with the notion of a “radical prostatectomy with curative intent.” Furthermore, Zincke et al.171 at the same institution previously demonstrated that the relative risk of failure was 1.3 times higher at 5 years if failure was defined as greater than 0.2 ng/ml compared with greater than 0.4 ng/ml. The importance of a detectable PSA was recently explored in detail, with a detectable PSA defined as failure to achieve PSA less than 0.03 ng/ml.172 A detectable PSA was associated with increased PSA recurrence and death (P < 0.001 and 0.041, respectively). In such patients the 1- and 5-year biochemical recurrence-free survival was 68% and 36%, significantly lower than 95% and 72%, respectively, in men without persistently detectable PSA. Overall survival at 10 years in patients with persistently detectable PSA was 63% versus 80% in patients without a persistently detectable PSA. Thus a persistently detectable PSA should not be ignored.172

FIGURE 45-8 • Biochemical progression-free percent using different prostate-specific antigen cut points to define progression after radical prostatectomy. Number of patients at risk for progression at 5, 7, and 10 years ranged 1354 to 1728, 497 to 703, and 53 to 83, respectively. Amling curves.170

Of note, however, there does exist a small subset of patients with a detectable PSA after radical prostatectomy but with little or no subsequent rise in PSA and no clinical progression with long-term follow-up.173 In one series they identified 14 patients (8.8% of PSA failures) with a detectable serum PSA level and a mean PSA velocity after recurrence of 0.028 ng/ml per year after radical prostatectomy but without clinical or continued PSA progression at 10 years. They concluded that there is a subset of patients with PSA failure after prostatectomy who will not progress and cautioned against the use of early salvage therapy without first observing the kinetics of PSA progression. The presence of benign glands in the resection bed may account for this uncommon phenomenon.174–176

Some investigators have chosen to use the ASTRO consensus definition for patients treated surgically.177 However, if such an approach was used following prostatectomy, it would seem most reasonable to require the use of an ultrasensitive definition, so that the date of first rise is not missed because of an insensitive assay.178,179

Standard Therapeutic Approaches

Radical Prostatectomy: Surgical Technique and Complications

The radical perineal prostatectomy and the radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP) for prostate cancer were first described by Young and Millin in 1905 and 1947, respectively.180,181 It was not until 1949 that Memmelaar first reported the successful use of the retropubic approach (RRP) for treatment of prostate cancer.182 However, in the 1950s and 1960s it was believed that radiotherapy provided comparable results with less morbidity. In late 1970s and early 1980s, Walsh and others demonstrated the value of performing a more sophisticated “anatomic” RRP to reduce blood loss, minimize the risk of incontinence, and preserve potency.183,184 With this advancement, the RRP became the surgical approach of choice in the eyes of most urologists. Thus the modern anatomic radical prostatectomy is only a few years older than 3-D conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT). Brachytherapy has been around longer than both.

Although there was a surge in the use of brachytherapy in the late 1990s and early 2000s, in recent years there has been a shift toward an increased number of radical prostatectomies driven by robotic approaches.185–187 It appears that the major outcomes (cancer control, potency, positive margin rates) with the robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) are comparable to open prostatectomies when performed by expert hands.188 Despite this fact, in the next 5 years, RALPs are projected to account for as many as 80% of the radical prostatectomy procedures performed in the United States. Most experts believe that RALP is associated with shorter recovery, less blood loss, lower use of pain medications, earlier catheter removal, and an improved ability to perform a nerve-sparing operation because of the magnified images. Up to 98% of patients can be expected to achieve continence (no pad use at 12 months) following either RALP or an open prostatectomy.189,190 However there is no good evidence that outcomes are better and in some series they are worse following a RALP (see discussion below).

Recent series have demonstrated potency rates following open prostatectomy of 68% to 90% within 6 to 18 months, with potency rates of 68% to 84% within 6 to 24 months following RALP.191–194 In a trial of 2702 men treated by the so-called minimally invasive prostatectomy or open prostatectomy, the risk of salvage radiation or HT up to 6 months after surgery was substantially higher in the former compared with the latter group (28% versus 9%).195 Also of note, Schroeck and colleagues evaluated patient satisfaction and regret following RALP or open RRP, and found that patients were three times more likely to be dissatisfied and regret their treatment decision following RALP than following open RRP. Presumably this reflected unmet patient expectations as they related to urinary morbidity, sexual function, and cancer-control rates.196 To date, studies have shown that RALP results in lower transfusion rates, lower use of pain medications, and shorter convalescence, but without an advantage in continence or potency; RALP is associated with higher cost.197 Hu investigated the merits of the so-called minimally invasive radical prostatectomy (MIRP) and compared it with the open RRP to determine the comparative effectiveness.198 They performed a population-based observational cohort study using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Medicare-linked data based on men who underwent MIRP (N = 1938) versus RRP (N = 6899) between 2003 and 2007. They noted that the use of MIRP increased from 9% in 2003 to 43% in 2006 and 2007. They also noted that use of the MIRP was associated with shorter length of stay (median, 2 versus 3 days; P < 0.001) and lower rates of blood transfusions (2.7% versus 20.8%; P < 0.001), postoperative respiratory complications (4.3% versus 6.6%; P = 0.004), miscellaneous surgical complications (4.3% versus 5.6%; P = 0.03), and anastomotic stricture (5.8% versus 14.0%; P < 0.001). However, they also noted that the use of the MIRP was associated with an increased risk of genitourinary complications (4.7% versus 2.1%; P = .001), including incontinence (15.9 versus 12.2 per 100 person-years; P = 0.02) and erectile dysfunction (26.8 versus 19.2 per 100 person-years; P = 0.009). Failure rates did not appear to differ by surgical approach.198

Although the evidence that RALP is associated with clinically meaningful outcomes is lacking, it is clear that surgical experience can have a significant effect on outcomes.199 Based on an analysis of surgery performed on more than 7000 patients by 72 surgeons, there appears to be a statistically significant association between biochemical recurrence and surgeon experience.199

Complications of Radical Prostatectomy

One of the major criticisms of radical prostatectomy is that, although it is a widely performed procedure, the results that are usually quoted by urologists are those of a relatively small handful of experts. The rates of postoperative and late urinary complications are significantly reduced if the procedure is performed in a high-volume hospital and by a surgeon who performs a large number of prostatectomies. Unfortunately, less than 10% of urologists qualified as “high-volume surgeons”; thus the results reported by a relatively small handful of surgeons are not likely to be representative of the results of the other 90% of urologists.200 Given this limitation, it is clear that numbers quoted in the following text are based on the published literature and once again have to be taken with “a grain of salt.” The randomized trial of watchful waiting versus prostatectomy provides an important assessment of the effect of surgery on the overall quality of life (QOL).201 Urinary leakage occurred in 49% versus 21% after radical prostatectomy compared with “watchful waiting”; however, bowel dysfunction, anxiety, depression, well-being, and subjective QOL were similar in the two groups.

Pelvic pain, impotence, transient incontinence, and slight shortening of the penile length are among the immediate complications associated with radical prostatectomy.202 The reported intraoperative blood loss is typically in the order of 500 ml to 1 L (range, 300-4320 ml). Techniques that minimize injury to the anterior periprostatic veins, the dorsal vein complex, the numerous small branches from the neurovascular bundles (NVBs), the seminal vesicles, and the base of the bladder reduce the risk of blood loss. Among most urologists, the retropubic radical prostatectomy appears to be favored because of the reduced risk of rectal injury and the ease of completing a pelvic lymphadenectomy.

Operative mortality nationally has been reported to be nearly 2%, but in the hands of an experienced surgeon the risk is reported to be substantially lower.203 Similarly, rectal injury may occur infrequently in less than 1% of patients when reported by experienced surgeons, but is substantially more common based on national statistics. Thromboembolic events have been reported to occur in approximately 1% to 3% of patients, whereas myocardial infarctions and wound infections are reported to occur in 1% or less in selected series. However, based on a national sample of 20% of Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older, nearly 8% suffered major myocardial infarctions within 30 days of surgery.203 Urinary stress incontinence is reported by experienced surgeons to occur in 5% to 14% of patients, but is much more common based on national statistics or surveyed patients.

Potency After Radical Prostatectomy

The most widely quoted result of potency preservation after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy has been reported in series from Johns Hopkins Medical Center and Washington University. Potency was reportedly maintained in approximately 60% of patients, with markedly better results in younger patients. At Washington University, patients younger than 60 years of age were reported to have a 68% likelihood of maintaining potency, versus 55% in patients 60 years or older. This patient selection phenomenon is highlighted by the prostatectomy series from Johns Hopkins, in which 86% of treated patients were potent preoperatively compared with only 50% of patients in the radiation series. It follows, as with other types of surgically induced morbidity, that the maintenance of potency depends on the skill and experience of the surgeon.200

In contrast, Robinson et al.204 recently updated a 1997 meta-analysis of rates of erectile function after treatment of localized prostate cancer. They conducted a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis of the rates of erectile dysfunction associated with the use of nerve-sparing and non–nerve sparing prostatectomies, brachytherapy (permanent seed implants) with and without EBRT and cryosurgery for localized prostate cancer. The probability of maintaining erectile function after brachytherapy, brachytherapy plus EBRT, EBRT alone, nerve-sparing and non–nerve sparing prostatectomy and cryosurgery were 0.76, 0.60, 0.55, 0.34, 0.25, and 0.13, respectively. The major shortcoming of this analysis, however, is the fact that these are physician-reported rates of erectile dysfunction.

A more contemporary assessment of the effect of radical prostatectomy (with and without nerve sparing), EBRT, and brachytherapy on the QOL of men undergoing treatment for localized prostate cancer can be found in the report by Sanda et al.205 They prospectively measured outcomes reported by 1201 patients and 625 spouses or partners at multiple centers before and after radical prostatectomy, brachytherapy, or EBRT using the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) and the Service Satisfaction Scale for Cancer Care.205–207 In their abstract they concluded, “Adjuvant hormone therapy was associated with worse outcomes across multiple quality-of-life domains among patients receiving brachytherapy or radiotherapy … and … [a]dverse effects of prostatectomy on sexual function were mitigated by nerve-sparing procedures.”

Unfortunately, the abstract failed to mention the most significant findings, and highlighted two of the least-relevant observations.208 Because adjuvant hormonal therapy (AHT) is supported by level I evidence for intermediate to high-risk patients treated with EBRT, highlighting the modest effect on QOL is misleading. In contrast, the single most remarkable QOL finding of this study was not even mentioned in the abstract. Despite starting with a higher mean sexual score at baseline and being 5 to 10 years younger, the mean sexual score of patients receiving prostatectomy had a much larger decline in sexual functioning at 2 years compared with those of patients receiving radiotherapy or brachytherapy. This finding should have been emphasized in the abstract and provided to patients who are attempting to make informed decisions about treatment.205

The randomized trial of watchful waiting versus prostatectomy provides an important multicenter international assessment of the effect of surgery on potency.201 These investigators surveyed 376 men treated on this trial and 87% of the men responded to the survey. All patients included were younger than 75 years of age, with the mean age being approximately 64.5 and 68.5 years at time of surgery and at the time of the survey, respectively. All were followed in excess of 1 year with the median follow-up being approximately 49 months, ample time for full recovery of function. In this study, erectile dysfunction occurred in 80% of men after radical prostatectomy compared with 45% on the watchful-waiting arm. To complicate matters further, potency is not an all-or-none phenomenon after prostatectomy. For example, in one report the authors noted that “no patient could get a hundred percent rigid penis any more” or “experience the exquisite sensation of inevitability, the so-called point ‘of no return,’ which is caused by contractions of seminal vesicles and prostate capsule.”209 These authors noted that it was not uncommon for men to abandon sexual intercourse because of orgasm-induced acute urinary incontinence.

Postoperative Radiotherapy: Adjuvant and Salvage Radiotherapy

Evidence for Adjuvant Radiotherapy

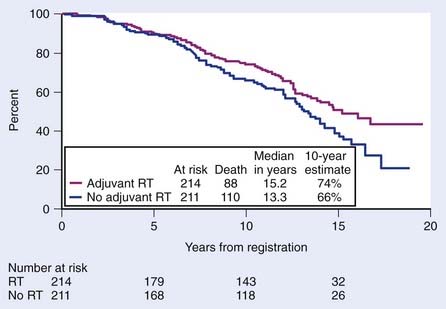

Support for postoperative EBRT following prostatectomy has grown with the completion of three phase III randomized trials demonstrating an improvement in biochemical failure, progression-free survival (PFS), time to metastasis, and overall survival.210–212 The most mature of these three trials conducted by the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) was recently updated.211 SWOG set out to determine whether adjuvant radiotherapy (ART) improves metastasis-free survival in patients with stage pT3N0M0 prostate cancer. In this study, 425 men were randomly assigned to receive 60 to 64 Gy of EBRT delivered to the prostatic fossa or observation (although, ultimately, 70 of these men received radiotherapy as well). ART resulted in an improvement in metastasis-free and overall survival compared with deferred therapy (HR 0.71; P = 0.016 and HR 0.72; P = 0.023, respectively). Among men randomized, there were 88 deaths of 214 on the radiotherapy arm versus 110 deaths of 211 on the observation arm (Fig. 45-9). Although adverse effects were more common with radiotherapy versus observation, by 5 years there were no differences in health-related QOL, and a subset analysis suggests that earlier treatment is better than delayed treatment.213,214

FIGURE 45-9 • Metastasis-free survival was significantly greater with radiotherapy (93 of 214 events on the radiotherapy arm versus 114 of 211 events on observation; hazard ratio [HR] 0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.54, 0.94; P = 0.016). Survival improved significantly with adjuvant radiation (88 deaths of 214 on the radiotherapy arm versus 110 deaths of 211 on observation; HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.55, 0.96; P = 0.023).211

The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) confirmed the value of ART, which reduces the risk of biochemical failure and prolongs the time to clinical progression.210 Patients eligible for this study had pN0M0 tumors and one or more pathologic risk factors (capsule perforation, positive margins, seminal vesicles invasion). After a median follow-up of 5 years, biochemical and clinical PFSs were significantly improved in the radiotherapy group (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0009, respectively). The rate of local regional failure was also lower in the radiotherapy group. Severe toxic toxicity (grade 3 or higher) was similar, being 2.6% versus 4.2% at 5 years in the postoperative radiotherapy group (P = 0.07). Most recently, a German series confirmed the benefits of ART with a low incidence of late complications from radiotherapy.212 With modern techniques it is expected that the relatively small risk of late complications could be reduced further (see the following discussion).

Salvage Radiotherapy

Salvage radiotherapy is the only curative option for patients experiencing biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy. There is a growing body of literature suggesting that early intervention with radiotherapy is better than delayed intervention for patients with biochemical failure.215,216 Support can be found in a matched-pair analysis from a multi-institutional database of 2299 patients undergoing postoperative radiotherapy. This analysis included patients with pT3-4N0 who received either salvage radiation therapy (SRT) or early ART.215,216 In total, 211 patients receiving ART and 238 patients receiving SRT were matched in a 1 : 1 ratio according to preoperative PSA GS, seminal vesicle invasion, surgical margin status, and follow-up from date of surgery. Early ART for pT3-4N0

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree