A neck dissection is the mainstay of the surgical treatment of many patients with cancer of the head and neck. A thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the neck is necessary to perform a neck dissection well. Such a discussion of the anatomy of the neck is not within the scope of this chapter. However, it is appropriate to highlight the pertinent surgical anatomy of certain structures that are particularly relevant, in the course of performing neck dissections.

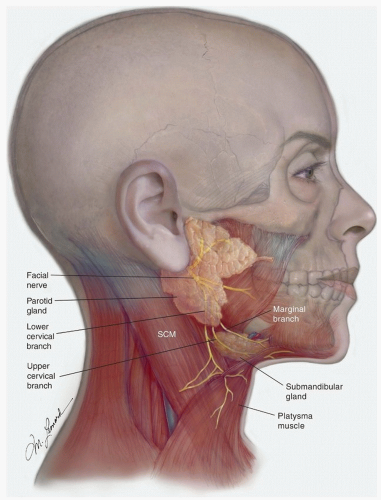

Marginal Mandibular Branch of the Facial Nerve

The inferior division of the facial nerve divides into cervical and marginal branches, a short but variable distance behind the anterior border of the lower portion of the parotid gland

(Fig. 18.2). The “lower” cervical branch runs downward and forward and, after exiting the parotid, is located between the anterior border of the parotid and the submandibular gland; it “terminates” in the platysma muscle, a variable distance below the submandibular gland. The marginal branch subdivides further, at about the level of the angle of the mandible, into an “upper” cervical branch and the marginal branch. The upper cervical branch overlies the posterior and then the inferior portions of the submandibular gland, as it curves upward to enter the platysma about 1.5 to 2 cm below the inferior border of the mandible. It is usually not possible to preserve the cervical branches of the facial nerve when performing a neck dissection that includes the submandibular triangle (level I). However, it is often possible to preserve these branches when performing a submandibular gland excision.

The marginal branch runs forward, in a slightly oblique, upward direction; it is located deep to the superficial cervical fascia, between the inferior border of the mandible and the superior border of the submandibular gland. When performing a neck dissection, this nerve is usually identified about 1 cm in front of and inferior to the angle of the mandible by incising the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia that envelops the submandibular gland, immediately above the gland, in a direction parallel to the direction of the nerve. The incised fascia then is gently pushed superiorly, exposing the nerve that lies deep to it but superficial to the adventitia of the anterior facial vein. The submandibular retrovascular lymph nodes are usually in close proximity and medial to the nerve and must be carefully dissected away from it. As this is done, the facial vessels are exposed and can be divided.

Identifying the marginal mandibular branch is essential in performing an adequate excision of the lymph nodes in the submandibular triangle. The practice of ligating the anterior facial vein low in the submandibular triangle and retracting it superiorly to “protect the marginal branch” can also result in elevation of the prevascular and retrovascular lymph nodes, thus precluding their appropriate removal. When indicated, it is preferable to identify the nerve and thoroughly remove these lymph nodes.

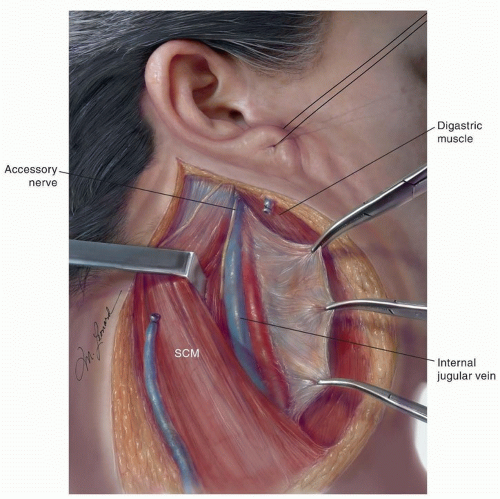

Spinal Accessory Nerve

The spinal accessory nerve (SAN) is located medial to the digastric and stylohyoid muscles and lateral or immediately posterior to the internal jugular vein (IJV)

(Fig. 18.3). Occasionally, the superior portion of the nerve is posterior-medial to the vein. The nerve then runs obliquely inferior and backward to reach the medial surface of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) near the junction of its superior and middle thirds (two to three fingerbreadths below the mastoiditis). Although the nerve can continue its downward course entirely medial to the muscle (18%), more commonly, it traverses and appears in the posterior border (82%).

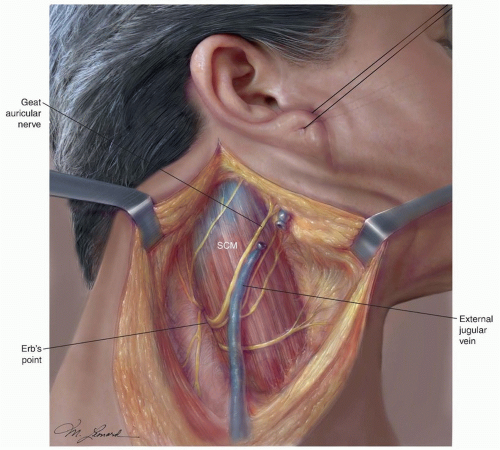

3 Here, the nerve is always located above the point where the greater auricular nerve turns around the posterior border of

the SCM, also known as Erb point

(Fig. 18.4).

4 The mean distance between the Erb point and the SAN is 10.7 mm, SD ± 6.3. It then runs through the posterior triangle of the neck and crosses the anterior border of the trapezius muscle. The mean distance between this point and the clavicle is 51.3 mm, SD ± 17.

4 Two anatomic characteristics of this portion of the nerve are relevant to avoid injuring it in the course of a neck dissection. First, the SAN is located rather superficially as it courses through the middle and low posterior triangle of the neck, and it can be easily injured while elevating the skin flaps in the posterior neck. Second, the nerve does not enter the trapezius muscle at the anterior border of it but courses along the deep surface of the muscle in close relationship with the transverse cervical vessels. Therefore, isolating the nerve to the level of the anterior border of the trapezius does not ensure its preservation during surgical dissection below this point, particularly in a bloody operative field.

A common sequela in patients who undergo neck dissection is related to the removal of the SAN or to dysfunction of this nerve subsequent to its dissection during surgery. The resulting paralysis or paresis of the trapezius muscle, one of the most important shoulder abductors, causes destabilization of the scapula with progressive flaring of it at the vertebral border, drooping, and lateral and anterior rotation. The loss of the trapezius function decreases the patient’s ability to abduct the shoulder above 90 degrees at the shoulder. Paralysis of the trapezius muscle causes a clinical syndrome characterized by weakness and deformity of the shoulder girdle, usually accompanied by pain.

5 The shoulder pain appears to be secondary to increased supportive demands on and strain of the levator scapulae and rhomboid muscles. Furthermore, adhesive capsulitis of the glenohumeral capsule may result in a “frozen shoulder” leading to a chronic disability and impaired quality of life.

6Preservation of the SAN to avoid this cumbersome sequela has been one of the reasons for the development of the modified radical and selective neck dissections (SNDs) that are commonly used today. Interestingly, varying degrees of shoulder dysfunction can occur, even when the SAN is preserved during a neck dissection. Therefore, it is important for the surgeon to understand the anatomy of the SAN and the importance of early diagnosis and rehabilitation when dysfunction occurs.

Nerve to the Levator Scapulae Muscle

The levator scapulae is a triangular muscle located deep in the lateral aspect of the neck, anterior and medial to the splenius capitis muscle. It extends from the transverse process of the atlas and the next three cervical vertebrae to the superior angle and the spine of the scapula. The action of the levator scapulae is to raise the medial angle of the scapula and incline the neck to the corresponding side with rotation of the neck in the same direction. With the trapezius muscle, the levator scapula makes a shoulder shrug possible. Because one of the functions of the levator is to draw the scapula and the shoulder upward and medially, inadvertent or unnecessary resection of the nerves to it during a neck dissection, particularly a radical neck dissection (RND), may accentuate the resulting deformity and functional disability of the shoulder.

The nerves to the levator scapulae, which vary in number from 1 to 3, branch off the 4th and 5th cervical nerves and travel posteriorly and inferiorly. They cross the anterior border of the levator scapulae and remain on the surface of the muscle for a short distance. The nerves to the levator scapulae are deep to the fascia of this muscle; thus, in the course of any neck dissection, but especially in an RND or an modified radical neck dissection (MRND), it is crucial to keep the plane of dissection superficial to the fascia of the levator in order to preserve these nerves. The dorsal scapular nerve is inconsistent in its anatomic relations in the posterior triangle of the neck and contributes to the innervation of the levator scapulae in a minority of cases.

7

Thoracic Duct

Inadvertent puncture or transection of the thoracic duct at the base of the neck can result in a chylous fistula, a relatively infrequent but potentially cumbersome complication of a neck dissection. Knowledge of the usual location and course of the thoracic duct is paramount whenever a dissection involves the supraclavicular, lower jugular (level IV) region. It is, perhaps, even more important when the surgeon is called on to search for and repair a chyle fistula during or after a neck dissection.

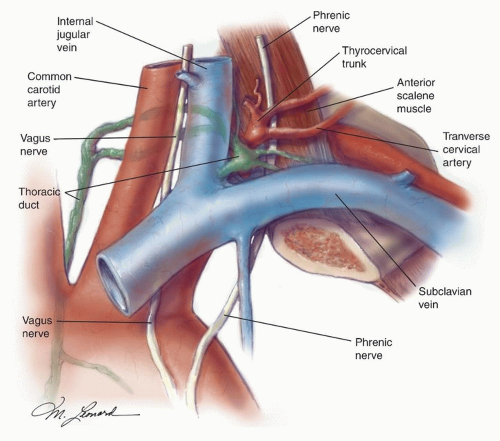

The thoracic duct is located medial to and behind the common carotid artery and the vagus nerve

(Fig. 18.5). From here, it arches upward, forward, and laterally, passing behind the IJV and in front of the anterior scalene muscle and the phrenic

nerve. It then opens into the IJV, the subclavian vein, or near the angle formed by the junction of these two vessels. The duct is anterior and medial to the thyrocervical trunk and the transverse cervical artery. To prevent a chyle leak, the surgeon also must remember that the thoracic duct may be multiple in its superior aspect and that at the base of the neck it usually receives a jugular, a subclavian, and other minor lymphatic trunks, which must be ligated or clipped individually.

Lymph Nodes of the Neck

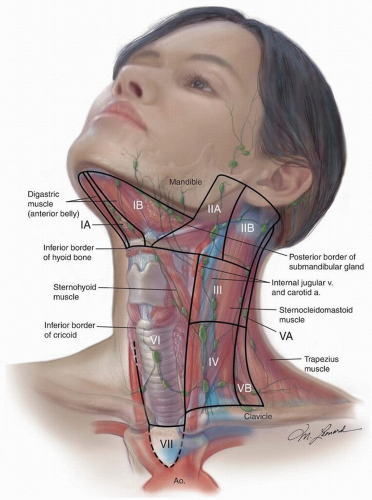

The lymph node regions of the neck are shown in

Figure 18.6. The six levels currently used encompass the complete topographic anatomy of the neck. The concept of sublevels has been introduced into the classification because certain zones have been identified within the six levels, which may have clinical significance.

Level I is divided into two sublevels. Sublevel IA (submental) includes the lymph nodes within the inferiorly based triangle bound by the anterior belly of the digastric muscles and the hyoid bone. Sublevel IB (submandibular) includes the lymph nodes within the boundaries of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, the stylohyoid muscle, and the inferior border of the body of the mandible.

Level II (upper deep jugular) includes the lymph nodes located around the upper third of the IJV and adjacent SAN extending from the level of the skull base to the level of the inferior border of the hyoid bone. The anterior/medial boundary is the stylohyoid muscle (the radiologic correlate is the vertical plane defined by the posterior surface of the submandibular gland), and the posterior (lateral) boundary is the posterior border of the SCM. Two sublevels are recognized in level II: sublevel IIA, nodes located anterior/medial to the vertical plane defined by the SAN, and sublevel IIB, nodes located posterior/lateral to the vertical plane defined by the SAN.

Level III (mid deep jugular) includes the lymph nodes located around the middle third of the IJV extending from the inferior border of the hyoid bone to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage. The anterior/medial boundary is the lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle, and the posterior/lateral boundary is the posterior border of the SCM.

Level IV (lower deep jugular) encompasses the lymph nodes located around the lower third of the IJV extending from the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage to the clavicle.

The anatomic boundary that separates the medial border of levels III and IV from the lateral border of level VI has traditionally been the lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle, a landmark that cannot be easily discerned on imaging studies. Therefore, the medial aspect of the common carotid artery has been suggested as an alternate boundary to separate these levels in an axial plane in imaging studies.

8Level V (posterior triangle) comprised predominantly of the lymph nodes located along the inferior half of the SAN and the transverse cervical artery. The supraclavicular nodes are also included in the posterior triangle group. The superior boundary is the apex formed by convergence of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, the inferior boundary is the clavicle, the anterior boundary is the posterior border of the SCM, and the posterior boundary is the anterior border of the trapezius muscle. A horizontal plane marking the inferior border of the anterior cricoid arch separates two sublevels. Sublevel VA, above this plane, includes the spinal accessory nodes. Sublevel VB, below this plane, includes the nodes that follow the transverse cervical vessels and the supraclavicular nodes with the exception of Virchow node, which is located in level IV.

Level VI (anterior compartment) lymph nodes in this compartment include the pre- and paratracheal nodes, precricoid (Delphian) node, and the perithyroidal nodes including the lymph nodes along the recurrent laryngeal nerves. The superior boundary is the hyoid bone, the inferior boundary is the suprasternal notch, and the lateral boundaries are the common carotid arteries.

Level VII refers to the extension of the paratracheal nodes below the suprasternal notch (the dividing line between levels VI and VII) to the level of the innominate artery.

Other Lymph Node Groups

Lymph nodes involving regions not located within these levels should be referred to by the name of their specific nodal group; examples of these are the superior mediastinal, the retropharyngeal, the periparotid, the buccinator, the postauricular, and the suboccipital lymph nodes.

The retropharyngeal lymph nodes (RPLNs) lie within a pad of adipose tissue located behind the posterior wall of the pharynx and anterior to the prevertebral fascia and the cervical sympathetic trunk and ganglion. This pad of adipose tissue extends from about the level of the carotid bifurcation to just inferior to the skull base. The RPLN are divided into medial and lateral groups; the medial group of nodes lies behind the pharyngeal midline at a level between the first and fourth cervical vertebrae. The lateral group of nodes, better known as the nodes of Rouviere, are contained within a sliver of adipose tissue located immediately medial to the internal carotid artery. The RPLN receive lymphatic drainage from the nasopharynx, tonsil fossa, the walls of the oropharynx and the hypopharynx, and the posterior ethmoid sinuses.