33 Cancer of the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses

Epidemiology, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

Malignancies arising from the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are relatively rare tumors of the head and neck. They account for only 3% of all upper respiratory tract cancers, with a yearly incidence of 1 per 100,000 people.1 Because of their rarity, these sites are grouped together in most published reports. It is often difficult to determine the exact site of origin, because most of these tumors present at an advanced stage and extensively involve adjacent sites. Among the tumors arising in this anatomic region, 60% to 90% involve the paranasal sinuses, the majority being in the maxillary antrum. There is a 2 : 1 male predominance for these tumors.2,3 Most patients with carcinomas arising in the sinonasal region are older than 40 years of age.2,4 Esthesioneuroblastoma may occur in much younger patients as well.

Unlike other upper and lower respiratory tract carcinomas, nasal cavity and paranasal sinus cancers have not been associated with cigarette smoking.5 Chronic sinusitis, although frequently coexistent with malignant tumors in this region, is not a causative agent.6 However, an increased risk of adenocarcinoma of the nasal cavity and ethmoid sinus has been associated with wood dust exposure.7–9 A meta-analysis of 11 published studies of men with wood-related occupations showed that the odds ratio for developing adenocarcinoma was 13.5, with the risk correlative with the quantity and duration of exposure.10 An increased risk (odds ratio 2.4) of developing squamous cell carcinomas of the sinonasal region was seen only among those employed for 30 or more years in jobs with exposure to fresh wood. Other industrial risk groups include leather tanners11 and nickel refinery workers (250-fold risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma of the maxillary antrum12 and more than 40-fold risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal cavity13). Thorotrast, a radioactive contrast medium used in the 1960s for radiographic studies of the maxillary sinus, is an established carcinogenic agent for maxillary sinus carcinoma.

Because of the relative rarity of sinonasal cancer, there are a lack of studies analyzing the underlying cytogenetic and molecular findings. In one of the few published reports, overexpression of p53 was found in 60% of sinonasal carcinomas, including 42 squamous cell carcinomas and 10 adenocarcinomas, in a Taiwanese study on Asian patients.14

Anatomy

Nasal Cavity

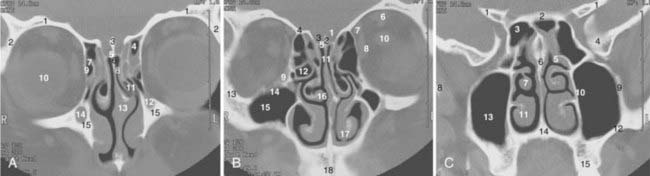

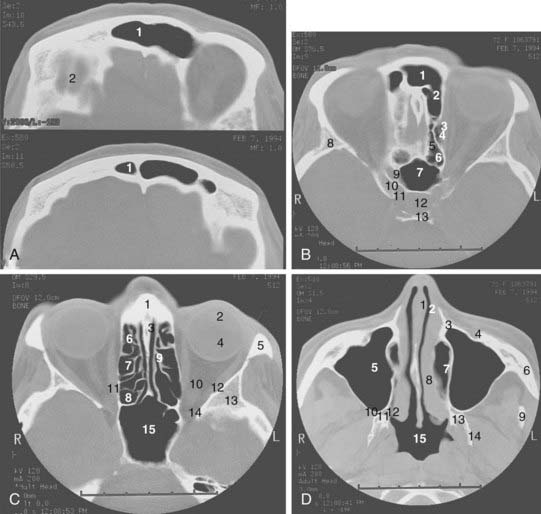

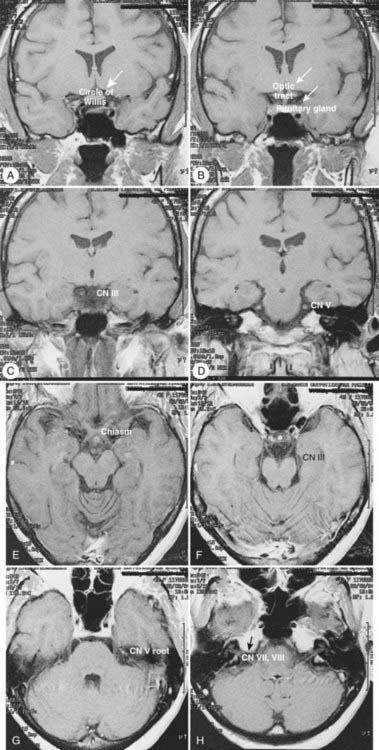

The coronal and transverse sections of the nasal cavity are illustrated in Fig. 33-1, Fig. 33-2, and Fig. 33-3. Anteriorly, the nasal cavity begins from the limen nasi, the line of transition from skin to mucous membrane. The nasopharynx is situated directly behind the nasal cavity and communicates with it by the posterior nasal aperture. Inferiorly, the floor is composed of the hard palate. Superiorly, the nasal cavity borders the base of the skull (frontal sinuses, cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, and ethmoid air cells). The medial walls of the maxillary sinuses define the lateral extent of the nasal cavity. The midline septum divides the nasal cavity into two halves. Three turbinates (or conchae)—superior, middle, and inferior—protrude downward and medially from the lateral wall into the nasal cavity, forming three meatus. The superior turbinate is much smaller than the middle and inferior turbinates, and is situated directly in front of the sphenoidal sinus. The nasolacrimal duct drains into the nasal cavity below the inferior turbinate.

Maxillary Sinus

The maxillary sinus (also called the maxillary antrum) is a pyramidal cavity (see Figs. 33-1C, 33-2D, and 33-3A) of approximately 15 cm3 volume (3.7 × 2.5 × 3.0 cm). The base of the pyramid is composed of the medial wall, which separates the maxillary sinus from the nasal cavity, and the apex is in the zygomatic process. Superiorly, the floor of the orbit forms the roof of the antrum. Anteriorly, the facial wall is located behind the cheek and curves inward into the sinus. Posteriorly, the infratemporal wall borders infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossae. The floor of the maxillary sinus lies inferior to the floor of the nasal cavity, especially in edentulous patients.15 Secretion from the maxillary sinus is drained into the nasal cavity via openings in the middle meatus. The medial wall of the sinus, of all its confines, is the most complex. It forms the inferior aspect of the lateral wall of the nose. Contained within it is the nasolacrimal duct. The exit of this duct is approximately 1 cm from the pyriform rim. The ostium of the maxillary antrum is traditionally described emptying into the posterior aspect of the hiatus semilunaris. The roots of the second premolar and first two molars penetrate the bony floor of the maxillary sinus.

Ethmoid Sinuses

The ethmoid cells, collectively called a sinus, lie between the nasal cavity and the orbit (see Figs. 33-1B, 33-2C, and 33-3B). The air cells, like a honeycomb, have the thin orbital plate of the frontal bone of the anterior cranial fossa for a roof (fovea ethmoidalis). They are grouped into anterior, middle, and posterior air cells on each side. The anterior cell is closely related to the frontal sinus and connects to the nasal cavity via the middle meatus. The middle ethmoid cell makes a bulge into the lateral wall of the nasal cavity (bulla ethmoidalis) and also communicates with the middle meatus. The posterior ethmoid cells are closely related to the optic canal and nerve, and open into the superior meatus. These openings between the nasal cavity and the ethmoid cells are an obvious route of tumor extension. The fragile medial wall of the orbit, formed by the lamina papyracea of the ethmoid bone, is extremely porous and is an easy conduit for tumor spread from the ethmoid sinus into the orbit. The superior portion of the nasal septum separates the right and left ethmoid cells. Most anterior ethmoid air cells extend within 1 cm of the anterior skin surface between the medial canthi. The orbits are conical and the ethmoid sinuses expand posteriorly and inferiorly to form the medial walls of the orbit. The optic nerves lie at about the same level as the roof of the ethmoid cells.16 The floor of the orbit rises posteriorly; thus the orbital apex lies superior to the inferior rim of the orbit.

Sphenoidal Sinus

The sphenoidal sinus is an air cavity within the body of the sphenoid bone. It is a midline structure located anterior to the clivus, posterior to the superior meatus of the nasal cavity (see Figs. 33-2B, 33-2C, and 33-3C). The lateral sphenoid sinus wall has a series of bulges and grooves corresponding to a number of vital structures that traverse the cranial side of its lateral walls. The cavernous sinuses lie lateral to the sphenoidal sinus with all their vessels (internal carotid artery) and cranial nerves (II, III, IV, V1, V2). The pituitary fossa and the optic chiasm lie above and the nasopharynx is located below the sphenoidal sinus. The sphenoidal sinus can be very extensive and may extend laterally between the maxillary nerve and the nerve of the pterygoid canal, inflating the greater wing of the sphenoid bone and pterygoid process. The sphenoidal sinus opens into the nasal cavity via the sphenoethmoid recess.

Frontal Sinus

The pair of frontal sinuses, located within the frontal bone, is irregular in size and shape and often represents an extension of an anterior ethmoid cell (see Figs. 33-1A and 33-2A). The sinuses lie above the orbits. Lined with respiratory epithelium, the frontal sinus drains into the maxillary sinus via the frontonasal duct.

Pathologic Conditions

The most common benign tumors arising in the sinonasal region are inflammatory polyps and benign mixed minor salivary gland tumors. Other tumors are histologically benign but behave in a locally aggressive and destructive manner. These tumors include inverted papillomas and midline granulomas. Inverted papillomas arise from squamous or schneiderian epithelium and most often involve the lateral nasal wall. They may destroy bone and tend to recur if not excised completely. From 10% to 15% of inverted papillomas are associated with malignant squamous degeneration.17,18 Inverted papillomas are best treated with en bloc resection with medial maxillectomy (recurrence rate <10%).18,19 Midline granuloma syndrome describes a process of progressive midline facial destruction from various causes including an immunologic or rheumatoid process and lymphomatous proliferation. Often a definitive diagnosis cannot be made on the basis of a biopsy. If the biopsy suggests Wegener granulomatosis, the treatment consists of systemic steroids or cytotoxic drugs or both. If the biopsy suggests lymphomatosis or reticulosis, the patient should have a systemic workup for lymphoma and be treated with localized radiation if no other disease is found. Midline lethal granuloma is a diagnosis of exclusion and describes progressive, painful destruction of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and hard palate. Death may eventually result from massive hemorrhage or infection once the base of the skull is eroded. The treatment for this condition is radiation therapy.

Melanoma and olfactory neuroblastoma, also known as esthesioneuroblastoma, are rare epithelial malignancies arising in the nasal cavity. Esthesioneuroblastoma originates from olfactory nerves and is considered a neuroendocrine tumor. It occurs predominantly in young patients between 10 and 20 years old, although a second peak is observed in an older group between the ages of 50 and 60 years.20–22 Olfactory neuroblastomas have a wide spectrum of clinical behavior. Some are slow-growing and tend to be localized, whereas others may be highly aggressive with local destruction and spread as well as distant metastasis. The incidence of cervical nodal involvement is 20%. The most common presenting symptoms are epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and a loss of the sense of smell. Mucosal melanomas are most often found in the nasal cavity and can be primary or metastatic. Overall, less than 1% of melanomas arise from the sinonasal tract. Nasal melanomas can often be amelanotic and may require immunohistochemical and electron-microscopic examination for definitive histologic diagnosis. Much more so than the cutaneous melanomas, nasal melanomas have a high incidence of local recurrence,23,24 and the patient may benefit from postoperative radiation therapy.

Undifferentiated carcinomas have been reported to represent a distinctive, rare, and highly aggressive neoplasm. They are composed of small- and medium-sized cells and have to be distinguished from melanoma, lymphoma, olfactory neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.25 They present at an advanced stage widely involving the nasal, maxillary, and ethmoid complexes. Orbital and intracranial extension is seen in the majority of cases. Prognosis is extremely poor, with 80% to 90% of patients dying within 1 year of extensive local and metastatic disease.26 The role of systemic chemotherapy as an adjunct to aggressive local therapy needs to be investigated.

Nonepithelial tumors include lymphoma, plasmacytoma, and sarcoma.

Clinical Presentation

Cervical lymph node metastases on initial presentation are uncommon; most large series report an incidence of less than 10% to 15%.27–29 Distant metastases on initial presentation are even less frequent, with a reported incidence of less than 5%.30

Routes of Spread

Perineural Spread

The sensory nerve supply of the maxillary, sphenoidal, and ethmoid sinuses; the nasal cavity and palate mucous membrane; the upper teeth and gums; and the adjacent facial skin extending from the lower lid to the upper lip, including the nasal vestibule, derives from the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V2). The anterior-superior alveolar branch of the infraorbital nerve runs in the facial wall of the maxillary sinus to the upper incisor and canine teeth. The posterior superior alveolar branch (dental nerve) pierces the infratemporal wall and supplies the mucosa of the maxillary antrum. The zygomatic nerve supplies sensory fibers to the lacrimal gland.31 Involvement of the nerve branches of the maxillary nerve by the tumor often leads to numbness and paresthesias in the skin and mucous membrane of this region.

Perineural extension into the central nervous system is more commonly associated with minor salivary gland tumors, especially with adenoid cystic carcinomas; however, it may occur also with other histologic types, especially in the setting of recurrence after surgery. Commonly involved nerves for perineural spread include olfactory nerves (from the cribriform plate into the anterior cranial fossa), the infraorbital nerve, and nerves that run through the superior orbital fissure (into the cavernous sinus or middle cranial fossa).32 Also commonly involved is the foramen rotundum, which transmits the maxillary nerve (cranial nerve V2) and carries sensory information from the lower eyelid and cheek into the trigeminal nucleus.

Diagnosis and Staging

Diagnosis

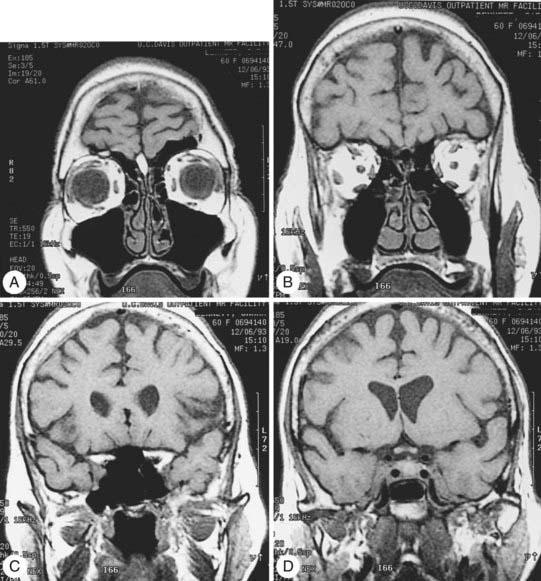

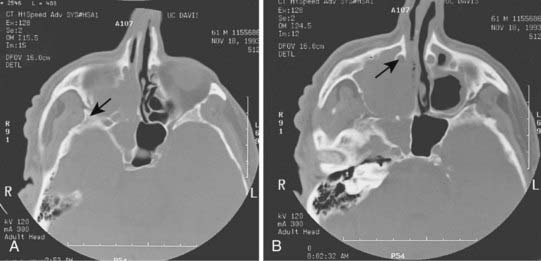

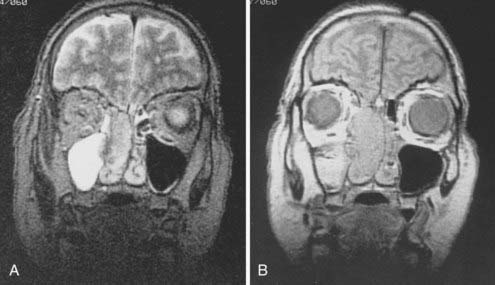

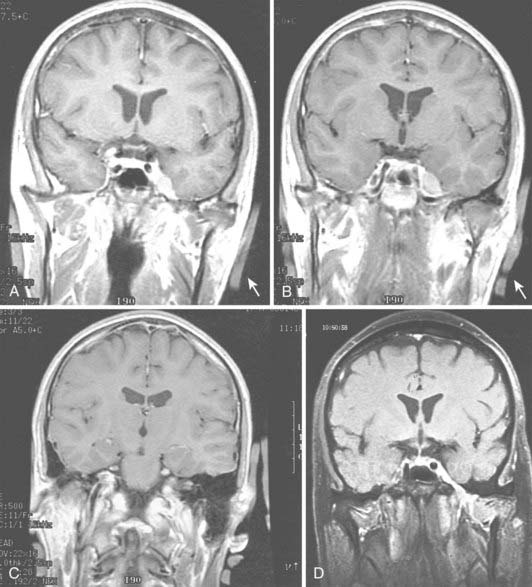

Radiologic evaluation is of paramount importance in the diagnosis and staging of nasal cavity and paranasal sinus tumors. Imaging has essentially replaced surgical exploration for staging and tumor mapping in this region. The most useful studies are computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT defines early cortical bone erosion more clearly (Fig. 33-4), whereas MRI better delineates soft tissue. MRI can also differentiate among opacification of the sinuses resulting from fluid, inflammation, or tumor (Fig. 33-5).32 CT performs better than MRI in evaluating thin bony structures, such as paranasal sinuses and orbita. MRI may demonstrate subtle perineural spread and involvement of the cranial nerve foramen and canals (Fig. 33-6 and Fig. 33-7).33 MRI is better than CT in evaluating intracranial or leptomeningeal spread. MRI is also more useful in assessing skull-base erosion. Sagittal and coronal MRI sections better visualize lesions involving the cribriform plate, basisphenoid, and floor of the middle cranial fossa.34 Thus, as a single modality, MRI may confer more information than CT.

Staging

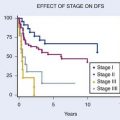

The staging classification for the epithelial tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses has been extensively revised in the sixth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis staging system (Table 33-1).35 In addition to the maxillary sinus, the nasoethmoid complex has been added as a second site with two regions within the site: the nasal cavity and ethmoid sinuses. The nasal cavity is further divided into four subsites: septum, floor, lateral wall, and vestibule. The ethmoid sinus region is subdivided into two subsites: right and left. For the maxillary sinus, T4 lesions have been divided into T4a (resectable) and T4b (unresectable), leading to the division of stage IV into stages IVA, IVB, and IVC. No widely accepted staging classification exists for frontal and sphenoidal tumors, as they are rare.

Treatment

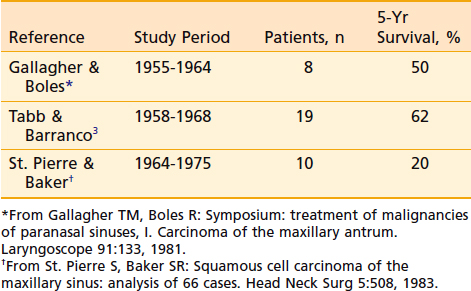

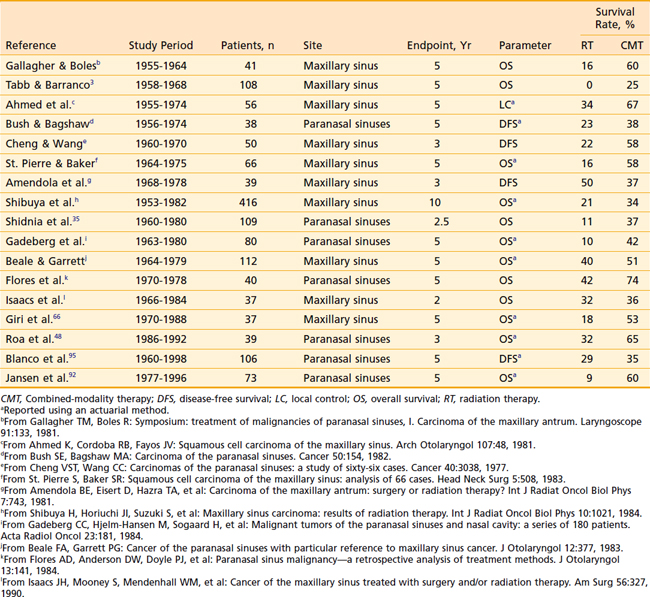

Although surgery alone or radiation therapy alone has been used with curative intent in the treatment of select nasal cavity or paranasal sinus carcinomas, most cases warrant combined-modality therapy (Table 33-2 and Table 33-3). In recent years, surgery followed by postoperative radiation therapy has been the mainstay of therapy for resectable lesions. Surgery is considered superior to radiation as a single modality for control of small lesions of the nasal septum or those limited to the infrastructure of the maxillary sinus.3 Although primary radiation therapy has a high cure rate for small squamous carcinomas of the nasal cavity, the potential for optic nerve injury from the high-dose radiation therapy required to achieve a good control rate must be considered. Massive tumors with extensive involvement of the nasopharynx, base of skull, sphenoidal sinuses, brain, or optic chiasm are considered unresectable. Some institutions have been studying the efficacy of combined radiation and radiosensitizing chemotherapy for unresectable squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Early results of this approach have been promising.36 If radiation therapy alone is to be used for large lesions, a hyperfractionated regimen may allow the delivery of higher doses than conventional radiation.

Table 33-2 Results of Treatment: Combined-Modality Therapy of Surgery and Radiation Therapy Compared With Definitive Radiation

Surgery

Surgical Procedures

The goal of surgery for nasal cavity and paranasal sinus tumors is to achieve en bloc resection of all involved bone and soft tissue with clear margins while maximizing the cosmetic and functional outcome. The extent and site of the incision depend on the location of the lesion. Limited nasal cavity lesions may be resected with medial maxillectomy. Ethmoid lesions usually require medial maxillectomy and en bloc ethmoidectomy. This is the most common surgical approach for inverted papillomas. The development of a combined craniofacial procedure for lesions involving the inferior surface of the cribriform plate and the roof of the ethmoid bone offers access to the anterior cranial fossa, orbit, and pterygopalatine fossa, and allows a rational oncologic resection, depending on anatomic considerations. In addition, this approach results in excellent cosmesis and improvement in the cure of lesions associated with extremely poor prognosis otherwise.37 The bony defect in the anterior cranial floor is closed with a vascularized pericranial or temporal muscle flap.

Primary surgery for maxillary antral cancers is radical maxillectomy that removes en bloc the entire maxilla and ethmoid sinus via a Weber-Fergusson incision. Patients with tumors limited to the infrastructure do well after surgery alone as long as the margins of resection are adequate. Suprastructure lesions may involve the orbit, necessitating orbital exenteration. Resection of involved periosteum and frozen-section control of adjacent orbital contents with preservation of the eye may be possible in select lesions with involvement of the periorbita without intraorbital extension. Orbital preservation surgery in select patients with involvement of the bony orbit but not soft tissue does not appear to result in poorer survival or local control than those undergoing exenteration.38,39 The radical maxillectomy defect is covered with a split-thickness skin graft. As a general rule, the surgical defect should not be obliterated during the initial surgery. An open cavity allows cleansing and direct visual inspection during follow-up.

Skull-Base Surgery

Base-of-skull surgery has been growing as a discipline of head and neck surgery, addressing the need for more radical resection of extensive tumors involving the frontal brain, cavernous sinus, sphenoidal sinus, clivus, pterygoid space, and petrous bone. The classic criteria for inoperability include (1) superior extension of the tumor through the dura into the frontal lobes; (2) posterior extension of the tumor beyond the cribriform plate and fovea ethmoidalis to a point at which there is excessive traction on the optic chiasm or invasion of the prevertebral fascia or both; (3) involvement of both optic nerves; and (4) lateral extension into the region of the superior orbital fissure and cavernous sinus.4 In a combined-team approach with neurosurgery, many previously unresectable sinonasal tract tumors are successfully resected at some centers. This technique is evolving, and outcomes of such aggressive surgery in those lesions with otherwise dismal prognosis need to be validated.