47 Cancer of the Male Urethra and Penis

In 2001, approximately 1.26 million people were diagnosed with cancer in the United States. Only 1200 cases were classified as cancers of the penis or male genitourinary malignancies (not bladder, ureter, prostate, or testis).1 The overall incidence based upon the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database is 0.6 per 100,000 for penile cancers and 0.3 per 100,000 for male urethral cancers. Analysis of the SEER database indicates that the incidence increases with age. Primary cancers of the penis and male urethra are extremely uncommon before the age of 55 (<1/100,000).2 Overall, primary penile and male urethral malignancies are relatively uncommon.

Primary Carcinoma of the Male Urethra

Incidence by Age

Primary carcinoma of the male urethra is extremely rare. Although cases have been reported in the literature as young as age 13, the SEER database records no cases in patients younger than the age of 20. The incidence increases with advancing age from 0.1 per 100,000 in patients ages 20 to 34, to a peak incidence of 2.6 per 100,000 in patients older than age 85.2

Etiology

No specific causal factors have been identified. However, chronic inflammation likely plays a role in the development of urethral cancers. Patients diagnosed with urethral cancers often have a history of prior sexually transmitted disease, urethritis, or urethral stricture. The incidence of urethral stricture in men diagnosed with carcinoma of the urethra ranges from 24% to 76%.3 The site of stricture is also the most likely site of malignancy.4 Approximately 10% of patients who undergo cystectomy for invasive bladder cancer also develop a urethral cancer distal to the urogenital diaphragm.

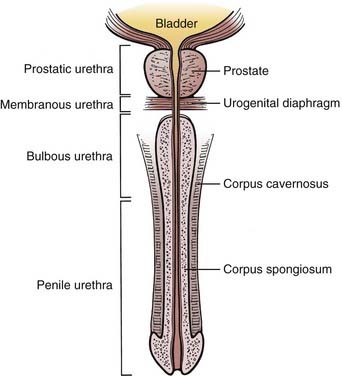

Anatomy

The male urethra, composed of a mucosa and submucosa, is approximately 20 cm in length and extends from the neck of the bladder to the external meatus of the glans penis. The prostatic urethra begins at the bladder neck and lies within the prostate. It is usually 3 cm long. It is the widest and most readily dilated portion of the urethra. It typically emerges anterior to the prostatic apex and merges with the membranous urethra. The membranous urethra lies within the urogenital diaphragm surrounded by the sphincter urethrae muscle and is the least dilatable portion of the urethra. The prostatic and membranous urethra are lined with transitional epithelium. The spongy (cavernous) urethra is enclosed in the corpus spongiosum. It is further subdivided into urethra confined by the penile bulb (bulbous urethra) and urethra distal to the bulb (penile or pendulous urethra). The narrowest portion of the urethra is the external meatus. The bulbomembranous urethra is known as the posterior urethra, while the penile urethra is referred to as the anterior urethra. Pseudostratified columnar epithelium lines the bulbous and penile urethra. Stratified squamous epithelium lines the urethra defined by the glans penis (Fig. 47-1). Numerous glands can be found in the submucosa of the urethra.

The bulbomembranous urethra is the most common site of primary malignancies (60%). Of these, 30% occur in the penile urethra, and 10% originate in the prostatic urethra.5

The anterior urethra drains into the superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes. The bulbomembranous and prostatic urethra drain into the pelvic lymph nodes. Posterior lesions may drain to the external and internal iliac, obturator, and presacral lymph nodes.6

Natural History

Primary urethral cancers are often insidious, and symptoms are often present only when the disease is locally advanced.7 The most common presenting symptoms include a palpable urethral mass, obstructive urinary symptoms, pain, urethral fistula or abscess, hematuria, or a palpable inguinal mass.8 Because many symptoms are not specific, symptoms have been reported to be present on average 5 months before diagnosis (range, 1 day to 15 years).9 Urethral carcinoma often directly invades adjacent structures such as the corpus spongiosum and periurethral tissues. Bulbomembranous lesions can extend into the urogenital diaphragm and prostate. Invasion into the corpora cavernosa is common at the time of diagnosis. Hematogenous spread (lung, brain, bone, lymph nodes) is relatively uncommon, except in locally advanced cases.10

Prognosis of male urethral carcinomas depends primarily on location and the degree of invasion. Anterior superficial lesions generally present earlier and carry the best prognosis, while deeply invasive lesions or those located posteriorly are rarely curable. Posterior lesions tend to be deeply invasive at the time of diagnosis. Histologic findings are thought to be less significant as a prognostic factor.11

Staging

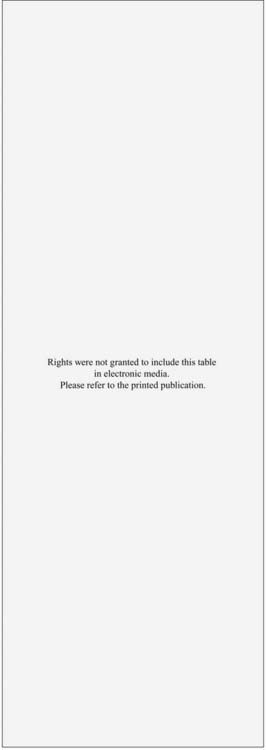

The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system set forth by the American Joint Committee on Cancer allows data collected by both physical examination and imaging in the staging of urethral cancers. T staging is determined mainly by the depth of invasion. Regional lymph nodes are considered to be the pelvic and inguinal nodal beds. Laterality does not affect the N status (Table 47-1).12

Table 47-1 Classification of Primary Urethral Carcinomas

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

Management

The role of radiation therapy alone for lesions in the distal urethra is not well defined but provides the option of organ preservation. Radiation therapy alone can be curative for distal lesions, with long-term cure rates similar to those reported for surgery. The most common approach uses external-beam radiotherapy with doses between 50 and 75 Gy.13

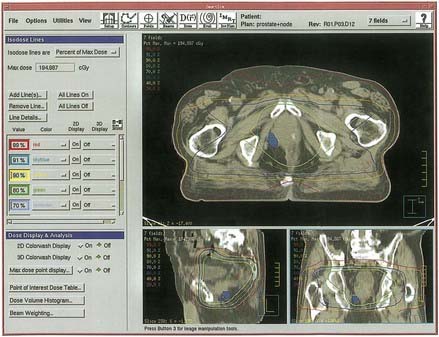

Local control may be more difficult to achieve in the bulbomembranous urethra because these lesions tend to be more locally aggressive (Fig. 47-2). Because metastasis tends to be a late event, aggressive combined approaches to local therapy should be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree