The larynx is eloquent, and even a tiny tumor can produce dramatic vocal changes that frequently allow for very early detection of disease. The American Cancer Society estimated that in 2013, there would be 12,260 laryngeal cancers and 3630 laryngeal cancer deaths. This progress that has been made for laryngeal cancer therapy has been one of the real success stories in head and neck cancer.1 Improved cure rates have allowed us to better tailor the treatment to the patient and, in doing so, to improve quality of life.

With surgery and radiation each progressing, there has been a near reversal of the definitive roles for each modality. Thirty years ago, many early laryngeal lesions were treated with radiation whereas many advanced lesions were treated with open surgery. Transoral laser surgery, better reconstructive surgery, Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT), concurrent chemotherapy, different fractionation schedules, improved imaging, speech pathology involvement are all factors that have all converged to improve preservation of function.

Treatment paradigms for advanced laryngeal cancer have evolved from a default position of total laryngectomy to careful consideration of laryngeal conservation when anatomically and medically possible. Carcinoma-in-situ (CIS) and T1/T2 disease are frequently handled with transoral laser surgery, and patients with T3 disease who have adequate laryngeal function are usually treated definitively with concurrent chemotherapy and radiation. For patients with bulky T4 disease or laryngeal cancers that cause aspiration, the standard management strategy is total laryngectomy followed by appropriate adjuvant therapy. On the other hand, for patients with T4 disease and functional larynxes, some centers are offering trials of nonsurgical management. Because those T4 patients who are either unresectable or medically inoperable are also treated with concurrent chemotherapy and external radiation retrospective comparisons of nonoperative versus operative approaches to T4 laryngeal disease are inherently suspect.

Understanding the anatomy of the region is crucial to designing the most appropriate treatment for each patient, and much of this chapter will be so focused.

Tumors of hypopharynx are far less “vocal” and large tumors or advanced stage at presentation are the rule rather than the exception. Partly due to their greater size and partly due to an overall worse prognosis, the outlook for patients with hypopharyngeal cancers remains suboptimal. CIS of the hypopharynx is very rarely detected, and most patients with a functional larynx and T1-T3 hypopharyngeal disease are offered concurrent chemoradiation. Assuming that the patients are medically fit and surgically resectable, laryngopharyngectomies are used for salvage or when patients have poor laryngeal function at presentation.

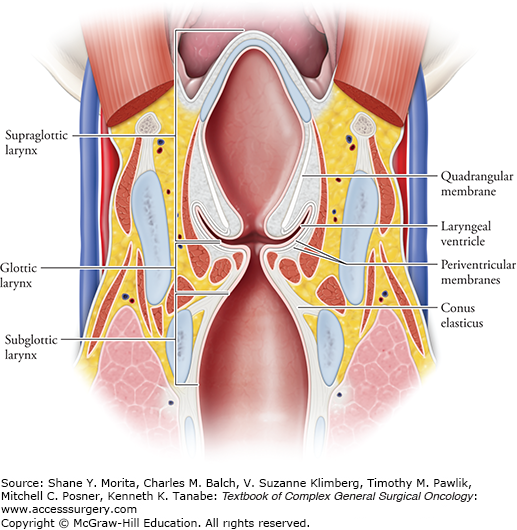

The larynx is divided into three regions: supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis (Figs. 55-1 to 55-8). The organ is inferior to the oropharynx, anterior to the hypopharynx, and sits astride the trachea. Compared to laryngeal cancers, hypopharyngeal tumors of the lateral and posterior pharyngeal walls, the postcricoid region, and the pyriform sinus have differing prognoses, and patterns of spread. In addition to its vocal function, the larynx protects the respiratory system from food and liquids that are better directed toward the esophageal inlet. The larynx also alters the expiratory airflow to produce sound. Be it singing, whispering, shouting, speaking, or gurgling, the voice is a fundamental form of communication. Conserving the laryngeal functions of airway protection and speech are central to treatment considerations for cancers of this region.

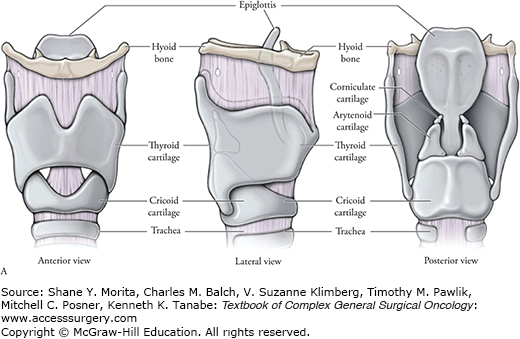

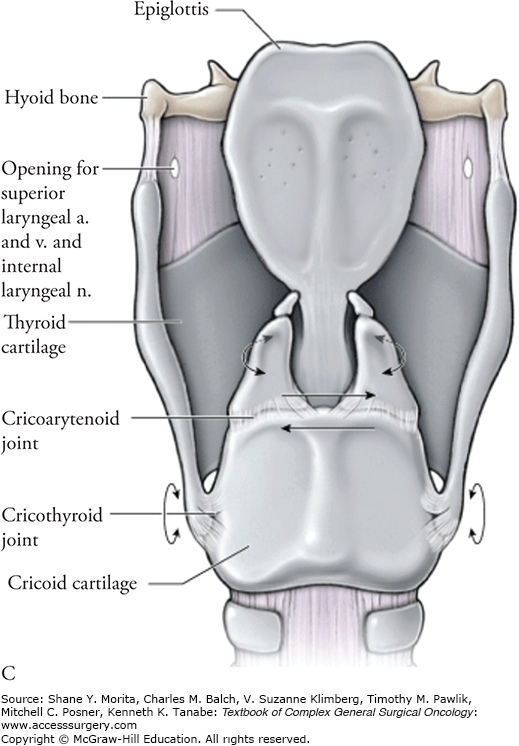

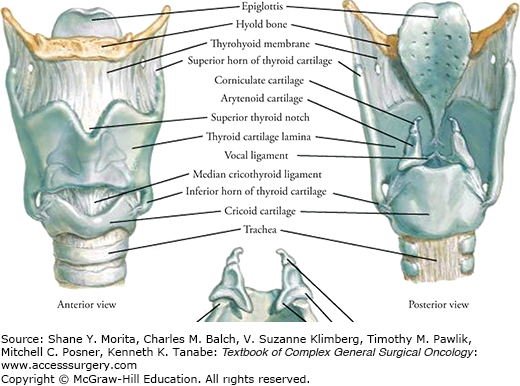

The laryngeal framework is composed of the hyoid bone, thyroid cartilage, and the cricoid cartilage. The hyoid bone is the simplest of the three large structures and has a main body that is midline in location and horizontal in orientation. Contiguous wings extend posterolateral and can confuse examination of the neck. It is sometimes difficult to differentiate an enlarged lymph node from the posterior aspect of the hyoid bone and rocking the hyoid bone will frequently make it clear to the examiner whether he/she has palpated an important lymph node or merely a portion of the hyoid.

The entire larynx moves vertically and anteriorly during swallowing with the hyoid bone being important to that function. The mylohyoid, geniohyoid, hyoglossis, and stylohyoid muscles, the stylohyoid ligament, and anterior and posterior digastric muscles, all insert onto the hyoid bone and cause laryngeal elevation. Conversely, the omohyoid, sternohyoid, thyroidhyoid also insert on the hyoid bone from the inferior aspect. Those muscles, plus the sternothyroid muscles pull the larynx inferiorly. Other muscles, the stylopharyngeus, salpingopharyngeus, palatopharyngeus (posterior tonsillar pillar) also elevate the larynx. This action is integral to swallowing while protecting the airway, and reshapes the supraglottis for voice manipulation.

The thyroid cartilage is said to be shield-like in appearance. Like a shield, it is clearly intended to face forward. The glottis, and the epiglottal root (sometimes known as the petiole but perhaps more formally called the base of the thyroepiglottic ligament), is attached to the midline, internal surface of the thyroid cartilage about a centimeter inferior to the thyroid notch. The attachment of the epiglottis is just superior to the anterior attachment of the glottis but they merge. Teleologically, it seems the shape of the thyroid was designed to protect the vital laryngeal structures located immediately posterior to it. The thyroid cartilage has bilateral superior and inferior horns. The superior horns extend about halfway up the full length of the thyrohyoid membrane, which is an important avenue for the escape of progressive cancers from the larynx.2

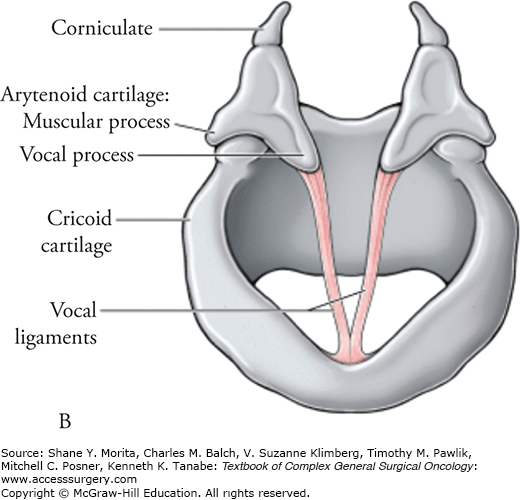

The most complex aspect of the laryngeal framework is the cricoid cartilage. The cricoid represents the only complete circle of the laryngeal scaffold, and adds considerably to its strength. A “U-bolt” with a solid plate across the back, the cricoid is much shorter anteriorly than posteriorly. On top of the posterolateral aspects of the cricoid, where the “U bolt” joins the plate, sit the two arytenoids. The arytenoids crown the cricoid and have the ability to swivel, loosening or tightening the vocal cords, as will be discussed below.

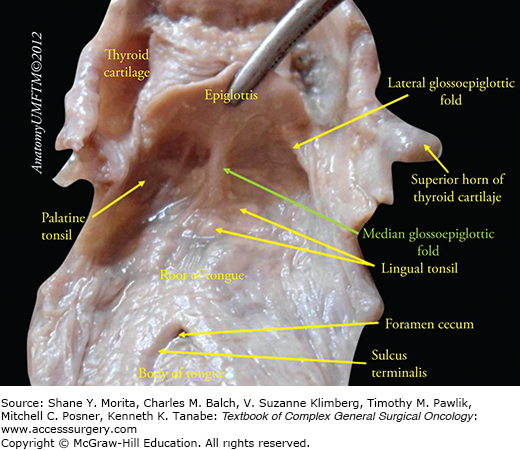

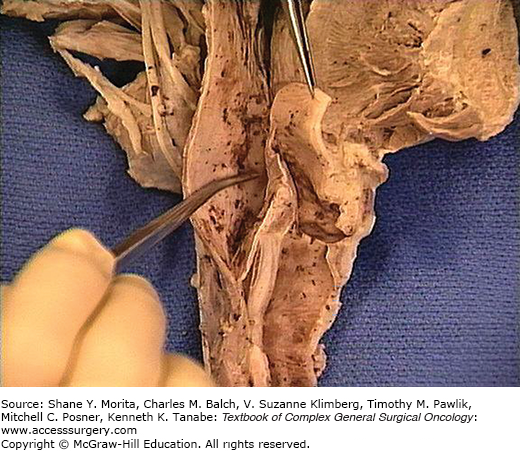

The dividing line between the oropharynx superiorly and the supraglottic larynx inferiorly is where the base of tongue abuts the lingual surface of the epiglottis. When evaluating any laryngeal cancer by inspection and palpation, it is important to appreciate whether there has been a spread to the vallecula, the most inferior and posterior portion of the base of tongue. Bringing an endoscope under the lingual surface of the suprahyoid portion of the epiglottis, and examining the median glossoepiglottic fold, which contains the ligament, is one excellent technique. Palpation can also be extremely valuable (Fig. 55-1).

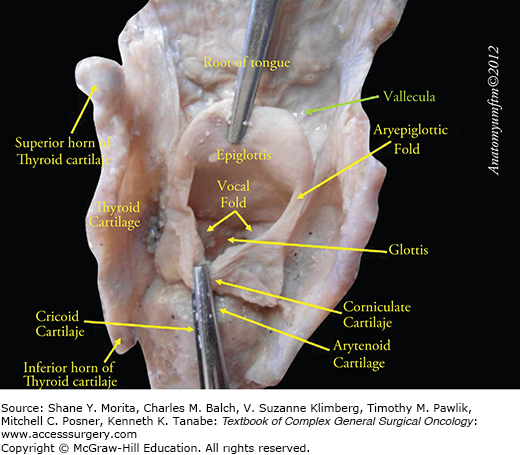

According to the AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook, 7th edition,3 the supraglottis has the following subsites: suprahyoid epiglottis, infrahyoid epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds (laryngeal aspect), arytenoids, and the ventricular bands (false cords). The arytenoids are part of the supraglottic larynx, which has ramifications for the proper staging of glottic cancers. In terms of patterns of spread, a better way to classify tumors of the epiglottis would be lingual versus laryngeal surface. Tumor of the lingual surface of the epiglottis is generally exophytic. On the other hand, owing to the porous nature of the cartilage of the laryngeal side of the epiglottis, cancers of the laryngeal side of the epiglottis tend to be infiltrative and frequently involve the pre-epiglottic space. Structurally the epiglottis dominates the supraglottic larynx. The epiglottis is shaped like a leaf, with the stem of the leaf attaching to the inner aspect of the thyroid cartilage in the midline (Figs. 55-2 to 55-8).

FIGURE 55-2

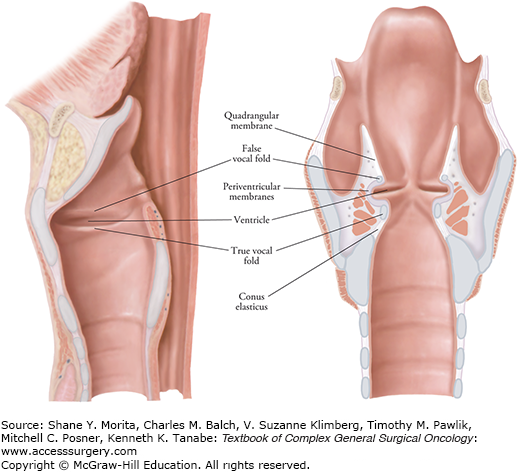

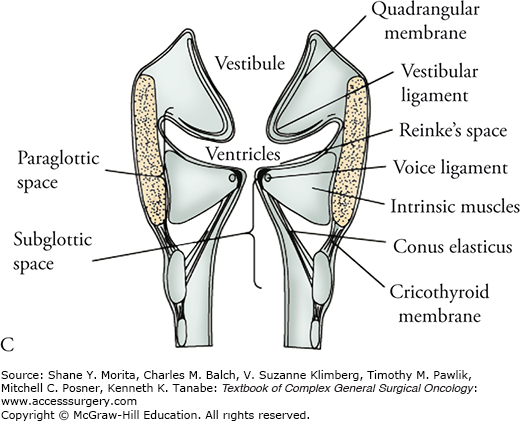

The leaf has developed posterior attachments that originate from its broadest portion and extend to the arytenoids—the aryepiglottic folds. The quadrangular membrane is the inferior extension of the aryepiglottic fold. Simplistically, the epiglottis is the anterior portion of the supraglottic larynx, the lateral aspects are the aryepiglottic folds and the inferior extension, the quadrangular membrane. The lateral defect in the supraglottic larynx is the laryngeal ventricle. The inferior extent of the quadrangular membrane forms the false cords. The inferior aspect of the supraglottic larynx is defined by a horizontal line passing through the junction of the ventricle with the superior surface of the vocal cords.3 (Used with permission from Wikimedia Commons.)

FIGURE 55-3

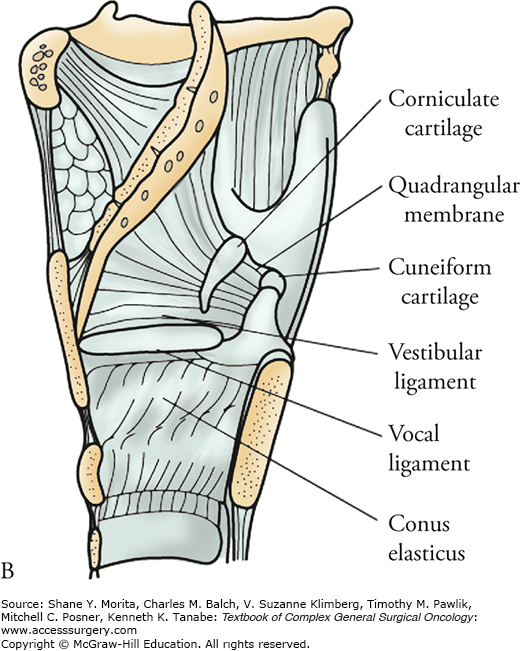

Looking at a vertical section through the larynx, it has been proposed that there are two fibroelastic membranes that tie the quadrangular membrane to the conus elasticus inferiorly, and thereby serve as barriers that help to protect the surface of the laryngeal ventricle from invasion by tumor.

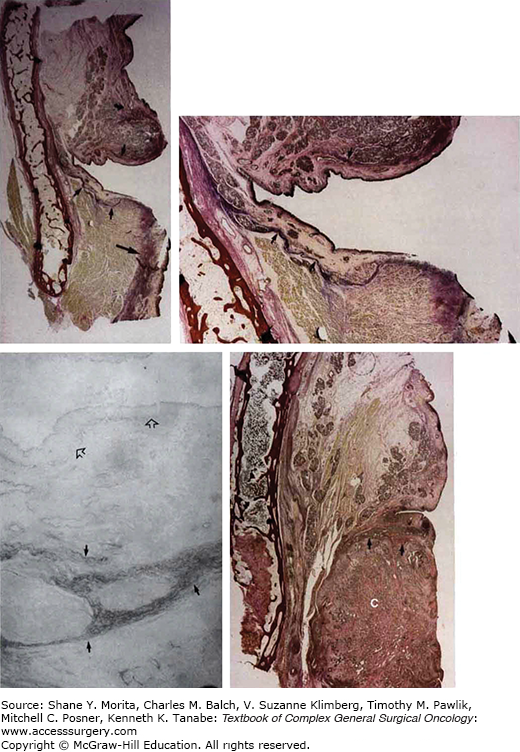

FIGURE 55-5

(Top, left, and right). Perpendicular section of vocal cords showing peripheral fibroelastic membrane (small arrows) in continuity with the conus elasticus (long arrows) and quadrangular membrane (curved arrows). (EVG stain of normal larynx at autopsy, [left] represents low power, original magnification 5×, and [right] is higher power, original magnification I 2×). Bottom left. Central, subepithelial elastic membrane (open arrows) underlying the ventricular mucosa and peripheral periventricular membrane (small arrows). (Orcein stain of normal larynx at autopsy, original magnification approximately 100). Bottom right. Peripheral fibroelastic membrane (small arrows) forming barrier to the spread of subglottic carcinoma (c) (H&E, original magnification 6×). (Reproduced with permission from Beitler JJ, Mahadevia PS, Silver CE, et al. New barriers to ventricular invasion in paraglottic laryngeal cancer, Cancer. May 15, 1994;73(10):2648–2652.)

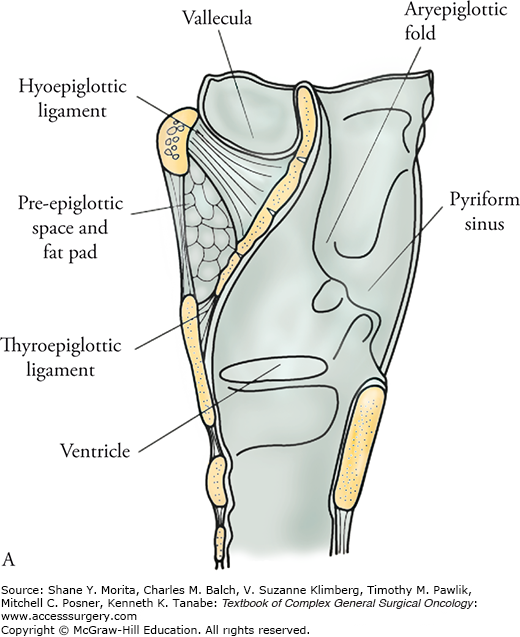

FIGURE 55-6

The pre-epiglottic space is a potential space that should appear as fat on CT or MRI imaging. Its borders can be easily remembered by visualizing a right triangle with the three apices being the posterior tip of the epiglottis, the attachment of the epiglottis to the thyroid cartilage, and the hyoid bone. That makes the anterior border of this triangle, going from superior to inferiorly—the hyoid bone, the thyrohyoid ligament, and the thyroid cartilage (until it meets the attachment of the thyroepiglottic ligament, or the petiole), which defines the inferior extent of the triangle. This border is termed the thyrohyoid ligament. The hypotenuse of the triangle is the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis. The superior surface of the triangle must connect the hyoid bone to the epiglottis and that ligament is thus the hyoepiglottic ligament. The hyoepiglottic ligament actually does not attach to the tip of the epiglottis, which extends superior to the level of the top of the hyoid bone, so there is a small area at the tip of the epiglottis, superior to the hyoid bone, that does not have a pre-epiglottic space. (Used with permission from Wikimedia Commons.)

FIGURE 55-8

Laryngeal membranes and ligaments act as barriers to tumor spread and define the paraglottic and pre-epiglottic spaces. A. Sagittal view, with mucosa intact and mucosa removed. B. Coronal view. (Reproduced with permission from Tucker HM. The Larynx. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1987.)

Owing partially to the functional importance of the glottis (the vocal cords), therapeutic choices are tailored to the depth and extent of disease. Understanding the microanatomy is crucial to making appropriate treatment recommendations. The true vocal cords, including both the anterior and posterior commissures, are the only subsites of the glottis.3 The glottis is 1 cm in height and extends inferiorly from the lateral margin of the ventricle (Fig. 55-4).

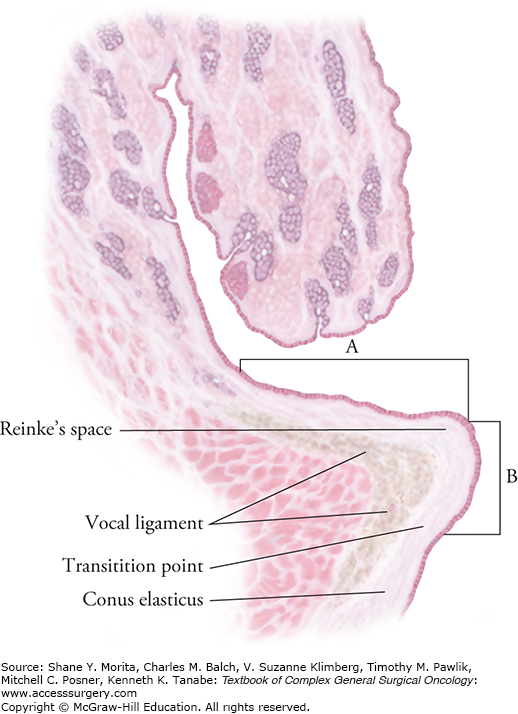

The glottis has an epithelial cap that sits on a basement membrane that covers the relatively thick lamina propia.4 The lamina propria, in turn, is superficial to the thyroarytenoid muscle, which is a key voluntary muscle that extends from the inner table of the thyroid cartilage to the vocal process of the arytenoid. The lamina propria is composed of three layers; the most well-known, and perhaps the most important, layer is Reinke’s space. Reinke’s space is a thick gelatinous film that is crucial to vocalization because it allows the epithelial layer to vibrate. In a remarkable work, Meyer-Breiting and Burkhardt examined 225 larynxes to measure the thickness of Reinke’s space.5 In the frontal plane, in the anterior portion of the vocal cord, the average thickness was approximately 1 mm, while further posteriorly, the average thickness seemed to be about 2.5 mm. Similar findings were found in the plane along the ventricular floor. Reinke’s space is very thin in the anterior 1/3 and much more robust from mid-cord and beyond (Fig. 55-9).

FIGURE 55-9

Reinke’s space and vocal ligaments in a 52-year-old man; coronal section through the middle third of a vocal cord. A. Horizontal extent. B. Vertical extent. (Adapted with permission from Meyer-Breiting E, Burkhardt A. Tumours of the Larynx: Histopathology and Clinical Inferences. Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag; 1988.)

The subglottis begins 1 cm inferior to the lateral margin of the ventricle (Fig. 55-4). Since the lateral margin of the ventricle is very difficult to appreciate in vivo, practically the subglottis is considered to begin 5 mm from the inferior portion of the free edge of the vocal cords and extends to the lower edge of the cricoid cartilage.3 The 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook does not list any subsites of the subglottis.3

The 7th edition of the AJCC Staging Handbook defines the hypopharynx as extending from a plane horizontal to the superior border of the hyoid bone to an inferior plane parallel to the lower border of the cricoid.3 Because of the similar patterns of spread (and a paucity of data), tumors of the posterior and lateral oropharyngeal walls are sometimes considered together with those of the hypopharyx.6 The hypopharynx itself is traditionally divided into three subsites: (1) posterior and lateral pharyngeal walls, (2) pyriform sinuses (right and left), (3) postcricoid region.

The majority of hypopharyngeal cancers originate from one of the pyriform sinuses7 and thus it is the most important subsite of the hypopharynx to understand. If the epiglottis is considered a roof to protect the laryngeal introitus from swallowed food, then the pyriform sinuses function as gutters that channel the bolus down either side of the lower throat and safely toward the postcricoid region and then on to the esophagus. When examining the patient, it is important to realize that the pyriform sinus is partially a potential space and may be collapsed. When the patient is awake, the pyriform sinuses may open with breathing, the Valsalva maneuver, or vocalization. These measures are necessary compromises and the direct exam under anesthesia remains the best way to examine the entirety of the mucosal surface of the pyriform sinus.

The pyriform sinus starts at the level of the pharyngoepiglottic ligament and the superior border is the aryepiglottic fold. The inferior extension of the medial wall is the quadrangular membrane, which is the lateral wall of the supraglottic larynx. The anterior portion of the pyriform sinus abuts the thyroid cartilage superiorly. The lateral wall can be thought of the projection of the medial wall onto the lateral pharynx that lines the inside of the thyroid cartilage superiorly and the cricoid inferiorly. It is crucial to appreciate (as illustrated below) that the inferior extent of the pyriform sinus, termed the apex, extends well below the level of the glottis, which may help explain why advanced pyriform sinus cancers cause vocal cord paralysis (which is part of the hypopharyngeal staging system) (Fig. 55-10).

The lateral and posterior pharyngeal walls are partly defined by exclusion. If the site is within the hypopharynx, but too lateral or posterior to reside within the pyriform sinus and too proximal or anterior to be in the postcricoid region, it is considered the posterior/lateral pharyngeal wall. Technically this zone has its superior border at the proximal portion of the hyoid and an inferior border at the lower border of the cricoid. It extends from the lateral aspect of one pyriform sinus to the other.

This is the anterior border of the hypopharynx and extends from one medial border of the pyriform sinus to the other medial border. The postcricoid region extends from the arytenoids to the inferior aspect of the cricoid.

Early lesions of the larynx and hypopharynx are chiefly defined in terms of their surface extent (Tables 55-1 to 55-5). More advanced cancers may alter function and impair vocal cord motion. Though staging criteria are explicit there is unfortunate room for “interpretation.” Experienced clinicians may disagree about vocal cord paralysis versus impaired vocal cord mobility. An important adjunct to routine mirror or fiberoptic examination of the larynx or hypopharynx is videstroboscopy. The latter can be performed in the clinic with topical anesthesia but does require specialized equipment. Videostroboscopy provides a high-resolution video of the larynx to assess tumor extent and because the strobe provides a slow motion view of the vocal cords, it is excellent for assessing impairment of the mucosal wave as well as mobility. Archiving the videostroboscopy images is useful as reference for assessing treatment response and success. Advanced primary cancers involve destruction and invasion invisible to the eye, and staging depends upon imaging. Generally T4b disease is considered unresectable and surgical judgment is required to make this determination.

Primary Tumor (T)a

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed. |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor. |

| Tis | Carcinoma-in-situ. |

| Supraglottis | |

| T1 | Tumor limited to one subsite of supraglottis with normal vocal cord mobility. |

| T2 | Tumor invades mucosa of more than one adjacent subsite of supraglottis or glottis or region outside the supraglottis (e.g., mucosa of base of tongue, vallecula, medial wall of pyriform sinus) without fixation of the larynx. |

| T3 | Tumor limited to larynx with vocal cord fixation and/or invades any of the following: postcricoid area, pre-epiglottic space, paraglottic space, and/or inner cortex of thyroid cartilage. |

| T4a | Moderately advanced local disease. |

| Tumor invades through the thyroid cartilage and/or invades tissues beyond the larynx (e.g., trachea, soft tissues of neck including deep extrinsic muscle of the tongue, strap muscles, thyroid, or esophagus). | |

| T4b | Very advanced local disease. |

| Tumor invades prevertebral space, encases carotid artery, or invades mediastinal structures. | |

| Glottis | |

| T1 | Tumor limited to the vocal cord(s) (may involve anterior or posterior commissure) with normal mobility. |

| T1a | Tumor limited to one vocal cord. |

| T1b | Tumor involves both vocal cords. |

| T2 | Tumor extends to supraglottis and/or subglottis and/or with impaired vocal cord mobility. |

| T3 | Tumor limited to the larynx with vocal cord fixation and/or invasion of paraglottic space and/or inner cortex of the thyroid cartilage. |

| T4a | Moderately advanced local disease. |

| Tumor invades through the outer cortex of the thyroid cartilage and/or invades tissues beyond the larynx (e.g., trachea, soft tissues of neck including deep extrinsic muscle of the tongue, strap muscles, thyroid, or esophagus). | |

| T4b | Very advanced local disease. |

| Tumor invades prevertebral space, encases carotid artery, or invades mediastinal structures. | |

| Subglottis | |

| T1 | Tumor limited to the subglottis. |

| T2 | Tumor extends to vocal cord(s) with normal or impaired mobility. |

| T3 | Tumor limited to larynx with vocal cord fixation. |

| T4a | Moderately advanced local disease. |

| Tumor invades cricoid or thyroid cartilage and/or invades tissues beyond the larynx (e.g., trachea, soft tissues of neck including deep extrinsic muscles of the tongue, strap muscles, thyroid, or esophagus). | |

| T4b | Very advanced local disease. |

| Tumor invades prevertebral space, encases carotid artery, or invades mediastinal structures. | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis. |

| N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, ≤3 cm in greatest dimension. |

| N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, >3 cm but ≤6 cm in greatest dimension. |

| Metastases in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension. | |

| Metastases in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension. | |

| N2a | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, >3 cm but ≤6 cm in greatest dimension. |

| N2b | Metastases in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension. |

| N2c | Metastases in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension. |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node, >6 cm in greatest dimension. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree