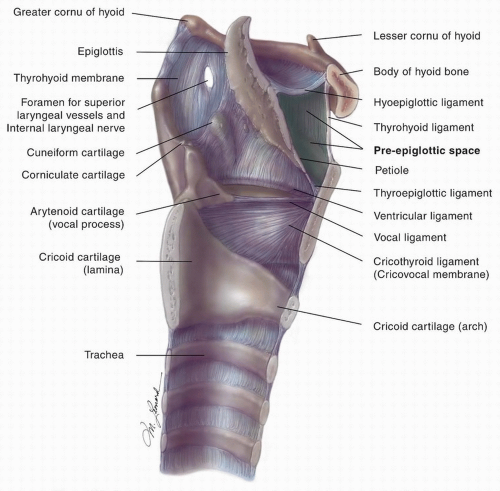

and (2) intermediate and deep layers of elastic and collagenous fibers that form the vocal ligament. Blood vessels and lymphatics are almost absent in Reinke space, creating a resistance to the spread of early cancer of the glottis. No mucous glands are found on the free edge of the vocal cord, and only sparse glands are noted on the superior aspect. The conus elasticus extends upward from the superior border of the cricoid cartilage to merge with the inferior surface of the vocal ligament; it has the capacity to resist the extralaryngeal spread of glottic and subglottic cancer.

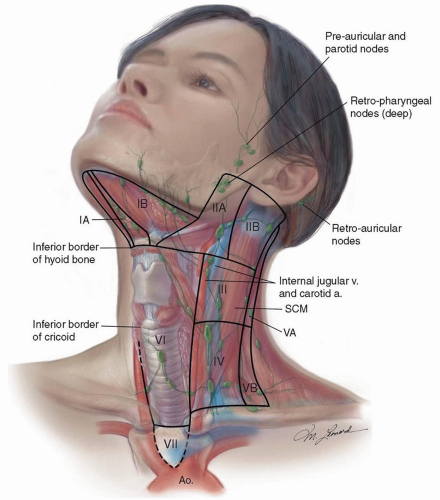

hypopharynx, and neck is critical. Indirect laryngoscopy (mirror examination) should be performed and supplements the findings of fiberoptic examination. Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy and/or videostroboscopy provide superior information about the anatomical and functional findings within the larynx and pharynx, which assist in treatment planning and staging. Careful palpation of the neck bilaterally is important with documentation of the location (group or level I to VI), size, mobility, and relationship of the node(s) to adjacent structures. Staging of the primary and the cervical lymph nodes is necessary prior to considering a patient’s treatment options.

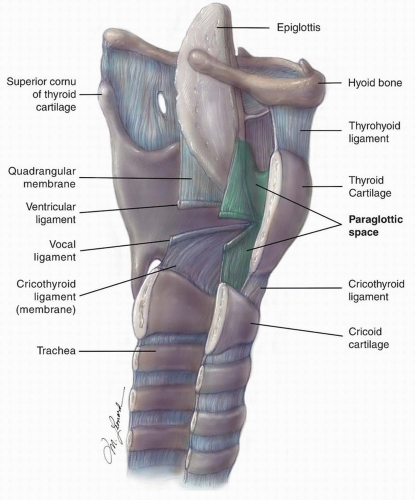

Figure 15.3. Sagittal cut of the larynx demonstrating the relative anatomy, highlighting the paraglottic space. |

examination. Preoperative pulmonary function testing should be considered along with history of activity level and exercise tolerance when making decisions about the suitability of a patient for partial laryngectomy. Consultations with other services, including radiation therapy, medical oncology, dentistry, speech pathology, psychiatry, and general medical services, are obtained as indicated.

staging (Table 15.1). The pathologic description of any neck dissection should describe the size, number, and level of involved lymph nodes, as well as whether extracapsular spread is present. Specimens should also be examined for the presence of lymphovascular and/or perineural invasion in the primary cancer resection.

Table 15.1 Stage Grouping | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 15.2 Definition of TNM | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

metastases are often associated with cancer of the supraglottic larynx. Esposito et al. reported a rate of occult regional spread of 27% in 97 N0 patients with previously untreated supraglottic carcinoma undergoing neck dissection at the time of horizontal laryngectomy. In this group, based on the preoperative staging of the cancer, 14% of cases had occult metastases involving lymph nodes in T1 cancer, 21% in T2 cancer, 35% in T3 cancer, and 75% in T4 cancer. The incidence of occult metastases was higher for the less differentiated cancer and for primary cancer with a higher T stage. In a subset of patients with lateralized supraglottic primary tumors, contralateral occult regional spread occurs in 37% of patients. The authors stressed the importance of bilateral regional nodal treatment with supraglottic tumors even in the N0 setting.23

primary site, and locoregional cancer recurrence (p = 0.028). Advanced regional metastases at initial diagnosis (N2 and N3 disease) increased the incidence of delayed and distant metastases threefold (p = 0.017). Incidences of delayed regional metastases by anatomic location of the primary cancer were glottic, 4.4%; supraglottic, 16%; subglottic, 11.5%; aryepiglottic fold, 21.9%; pyriform sinus, 31.1%; and posterior wall of the hypopharynx, 18.5%. Delayed regional metastases to the ipsilateral-treated neck had a significantly worse survival prognosis than did delayed metastases to the contralateral untreated neck.24

Mild—Changes are limited to the lower third of the epithelial thickness.

Moderate—Changes are limited to the lower two-thirds of the epithelial thickness.

Severe—Changes involve more than the lower two-thirds of the epithelial thickness. Cells are less crowded than with CIS and usually reveal greater differentiation.

radiation over a 43-year period. In the series, there were no reported episodes of posttreatment anaplastic transformation. Disease-specific survival was also noted to be comparable to those from series reporting on surgical management; however, local control (66% at 5 years) was noted to be inferior in comparison to surgery. Individuals who experienced a local recurrence (21/62) were capable of undergoing successful salvage resection of persistent cancer.34

the cricoid, and a variety of techniques have been described to reconstruct the larynx following partial resection with reconstruction of the cricoid, using hyoid bone, rib, and strap muscle. High-grade chondrosarcomas usually require a total laryngectomy, with neck dissection reserved for clinical or radiographic evidence of metastasis.

the potential for a satisfactory result with salvage partial laryngectomy. The treatment of cancer of the larynx should be individualized with various treatment modalities and surgical procedures according to the size and extent of the cancer, the age and physical condition of the patient, and the skill and experience of the treating physicians.

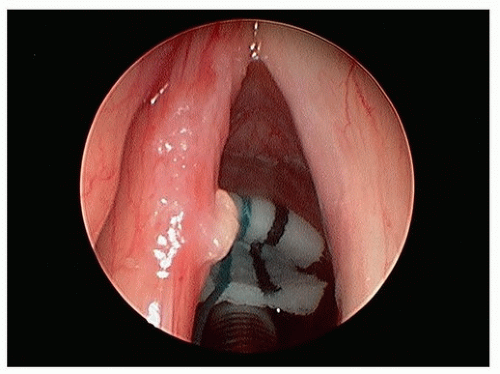

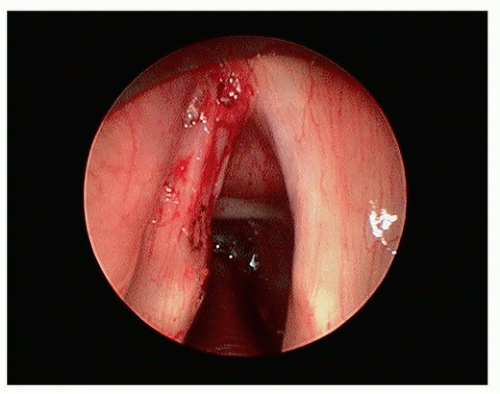

Figure 15.6. T1a glottic carcinoma after TLM (using CO2 laser) resection of tumor potential paths of spread of tumor within the laryngeal ventricle. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree