31 Cancer of the Larynx

Epidemiology, Etiology, and Genetics

Larynx cancers are the most common malignancy of the upper aerodigestive tract; they account for nearly 1% of all malignancies and approximately 25% of head and neck tumors. The estimated number of newly diagnosed larynx cancers in 2008 is 12,250, and the estimated number of deaths from larynx cancer is 3670.1 Primary glottic cancers are approximately three times more common than supraglottic tumors; tumors of the subglottic larynx are exceedingly rare, accounting for approximately 1% to 2% of all larynx cancers. Nearly 80% of larynx cancers occur in men. Larynx cancer is the most curable cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract, but the 5-year survival rate of approximately 65% has remained relatively unchanged during the previous three decades.2 In fact, larynx cancer represents one of the only malignancies for which the 5-year survival has not improved during this period. Great strides, however, have been made with regard to organ preservation in the treatment of this disease, and the majority of patients are now treated with upfront organ preservation protocols.

It is estimated that 75% of larynx cancers are attributable to cigarette smoking and alcohol use. A large international head and neck cancer epidemiology consortium found that the relative risk of smoking is more modest than previously believed.3 After cessation of smoking, the excess risk gradually declines and is no longer evident after 20 years.4 For many years, alcohol and tobacco were thought to act synergistically,5 but more recent data suggests that the two are independent risk factors.3 The effect of smoking and alcohol is greater for supraglottic cancers than glottic cancers.6 People who employ their voices extensively in their work also appear to be at higher risk of developing larynx cancer. In addition, occupational exposure to asbestos, diesel fumes, rubber, and wood dust may contribute to the development of larynx cancer, but a history of tobacco use is also generally present.6 Vitamin and nutrient deficiencies may contribute to the development of larynx cancer.7 Several studies have also implicated gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in the development of larynx cancer, especially in patients without a history of alcohol or tobacco use.8,9 GERD leads to chronic irritation of the larynx, which may lead to the development of larynx cancer. Human papillomavirus is strongly associated with tonsillar cancer, but its role in the etiology of larynx cancer is much less established.10,11

A molecular etiology for larynx cancer is emerging.12,13 Alterations in a variety of chromosomes, oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, growth factors, and a number of other cell-cycle regulators have been identified. Mutations in p53, Ki-67, Chek-2, EGFR, h-TERT, cyclin D1, cathepsin D, and TGF-B have been identified.14–16 P53 is the most commonly mutated tumor suppressor gene in human cancers. Mutation of the p53 gene is seen in nearly 50% of the patients who are cigarette smokers, but in only 14% of those who are nonsmokers. P53 mutations were identified in 55% of the tumors among drinkers and 20% among nondrinkers.17 Changes in p53 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression may be associated with human papillomavirus infection and could play a role in the carcinogenesis of laryngeal cancer.18 Some have advocated that the overexpression of p53 is associated with tumor bulk and poor local control in T1 glottic cancer, whereas others have failed to identify p53 status as a marker for prognosis and clinical outcome in laryngeal carcinoma.19,20 It is becoming increasingly clear that tumors of the larynx may represent a heterogenous group of neoplasms. Two frequently involved alleles are 3p and 9p21; these regions harbor tumor suppressor genes and thus may be involved with malignant transformation. Telomerase activity is often present at high levels in laryngeal cancer and may be an early event in the tumorigenic process.

Anatomy

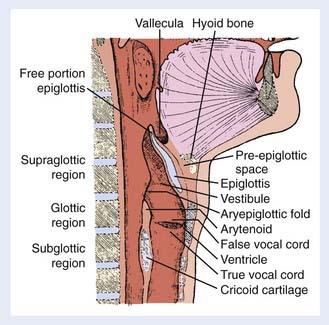

The larynx is a hollow tube lined by mucosa and adapted for protection of the airway and phonation. It is composed of the thyroid, cricoid, and arytenoid cartilages surrounded by connective and muscular tissue. The larynx is subdivided into three anatomical regions: the supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis regions (Fig. 31-1). The supraglottic larynx is composed of the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, arytenoids, and false cords (ventricular bands). The epiglottis is divided into a suprahyoid and infrahyoid component based on its relation to the hyoid bone. The supraglottic larynx extends from the tip of the epiglottis superiorly to the superior surface of the true vocal cords. The glottic larynx consists of the true vocal cords and the anterior and posterior commissures (the mucosa between the arytenoids). The true vocal cords are, on average, 2 cm long and are thinnest anteriorly and posteriorly. Most lesions arise on the free edge and upper surface of the anterior two thirds of the vocal cords and frequently extend to the anterior commissure. The lower boundary of the glottis is a horizontal plane 1 cm below the apex of the ventricle, or 0.5 cm below the free edge of the true vocal cords. Head and neck surgeons typically refer to the former definition and radiation oncologists refer to the latter. The subglottis extends down to the inferior margin of the cricoid cartilage and the beginning of the trachea.

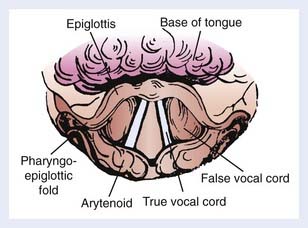

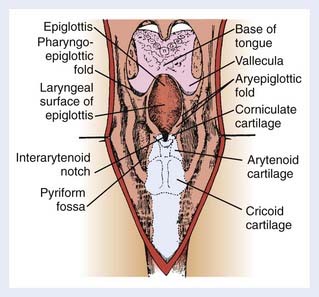

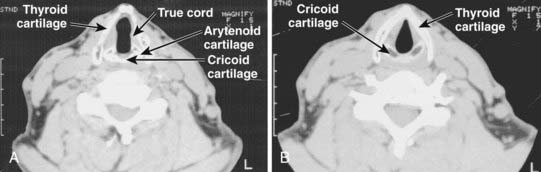

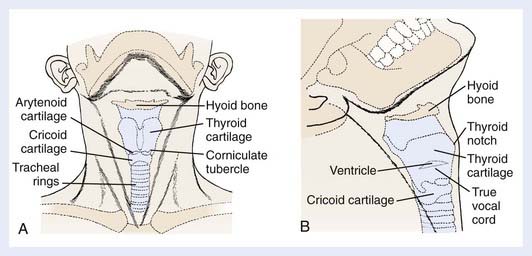

The appearance of the larynx as seen in the indirect mirror examination is shown in Fig. 31-2. The cartilaginous framework of the larynx is important in diagnostic radiology and in evaluating simulation and port films. The relationship of the various cartilages to surface anatomy is shown in Fig. 31-3. The thyroid, cricoid, and the majority of the arytenoid cartilages are composed of hyaline cartilage, which begins to ossify at approximately 20 years of age. The epiglottis, the corniculate and cuneiform cartilages, and the apex and vocal process of the arytenoids are made up of elastic cartilage, which does not ossify and therefore is not radiopaque.

FIGURE 31-3 • A, Anterior view of surface anatomy with cartilages shown. B, Lateral view of surface anatomy with cartilages shown.

The anterior limits of the larynx consist of the lingual surface of the suprahyoid epiglottis, the thyrohyoid membrane, the anterior commissure, and the anterior wall of the subglottic region, which is composed of the thyroid cartilage, the cricothyroid membrane, and the anterior arch of the cricoid cartilage (see Fig. 31-3B). To avoid underdosing the anterior portion of the larynx when using megavoltage radiation to treat larynx cancer, it is important to remember that the anterior commissure usually lies within 1 cm of the skin surface and that bolus may be required to deliver adequate dose to this area. The posterior and lateral limits include the aryepiglottic folds, the arytenoids, the interarytenoid space, and the posterior surface of the subglottic space formed by the mucous membrane covering the cricoid cartilage. Superiorly, the epiglottis demarcates the boundary with the pharynx, which is usually at the lower border of the C3 vertebra. The inferior extent of the larynx is at the lower margin of the cricoid, which is typically at the level of the C6 vertebra (Fig. 31-4). The anatomy of the larynx can also be appreciated on computed tomography (CT) scans. The key structures are seen in Fig. 31-5.

Routes of Spread

Lymphatics

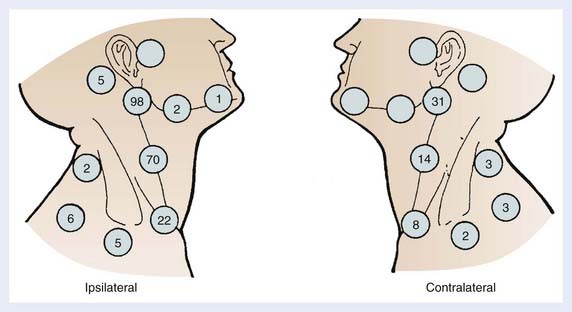

The supraglottis has a rich lymphatic network. Because of its midline location, it has a high propensity for bilateral lymph node involvement. The lymphatic channels from the supraglottis pass through the thyrohyoid membrane and drain into the jugular chain; thus the primary drainage pattern of supraglottic tumors is the jugular lymph node chain. The distribution of lymph node metastases for supraglottic cancers was identified in a large series of more than 2000 patients with SCC of the head and neck treated at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and is shown in Fig. 31-6.21 The subdigastric (also known as jugulodigastric, upper jugular or level II) are most commonly involved, followed by the midjugular (jugulocarotid or level III) and lower jugular (jugulo-omohyoid or level IV) nodes. The posterior cervical nodes (level V) are seldom involved, and submandibular (level IB) and submental (level IA) are almost never involved. The overall incidence of clinically involved lymph node metastasis from carcinoma of the supraglottis at the time of diagnosis is 55%, with 16% being bilateral. In addition, up to one half of the remaining clinically node-negative patients have pathologic nodal involvement on elective neck dissection.21–24 The extent of lymph node involvement correlates with tumor size and grade.25 The risk of clinically involved lymph nodes is approximately 40% for T1 and T2 tumors and approximately 60% for T3 and T4 lesions.

FIGURE 31-6 • Distribution of lymph node metastases from carcinoma of the supraglottic larynx.

(From Lindberg RD: Distribution of cervical lymph node metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the upper respiratory and digestive tracts, Cancer 29:1446, 1450, 1992.)

The lymphatic network is less developed in the subglottis and the risk of lymph node metastases is lower compared with supraglottic lesions. The incidence of lymph node metastasis from carcinoma of the subglottis varies from 20% to 50%.26,27 Lymphatic channels from the subglottic area unite to form three lymphatic pedicles, one anteriorly and two posterolaterally. The anterior channels pass through the cricothyroid membrane and drain into the middle and lower jugular nodes or terminate in the prelaryngeal node (Delphian node), from which lymphatics drain into the pretracheal and supraclavicular nodes. The posterolateral lymphatic channels pass through cricotracheal membrane and terminate in the high paratracheal nodes. Mediastinal involvement can occur but is unlikely even for subglottic tumors and when present is considered metastatic disease.

The true vocal cords are nearly devoid of lymphatic capillaries. Thus, for carcinoma of the vocal cords, the incidence of lymph node metastasis at diagnosis approaches zero for T1, 2% for T2, 15% to 20% for T3, and 20% to 30% for T4 lesions.28 In addition, the rate of occult nodal involvement is approximately 16% in patients with clinical T3 and T4 node-negative tumors who undergo elective nodal dissection.23 Lymphatic spread from glottic cancer primarily occurs when there is tumor extension into the supraglottis or the subglottis, where the lymphatic supply is much more extensive. However, the incidence of lymph node metastasis from primary vocal cord carcinomas with supraglottic or subglottic involvement is not as high as the incidence of nodal involvement with primary supraglottic or subglottic carcinomas.

Distant Metastases

The incidence of clinically distant metastasis is relatively low for larynx cancer, but metastases are identified in approximately 10% to 20% of patients, the majority of whom have supraglottic and subglottic primary.29,30 Autopsy studies, however, show that the rate of subclinical metastases is much higher.31 The lung is the most common distant metastatic site and is the first site of presentation in nearly 60% of patients. Bones are the second most common site, as 20% of patients with distant disease develop osseous metastases. Liver metastases are identified clinically in 10% of patients. Brain metastases have been reported but are exceedingly rare.32 Because these patients are usually at high risk for developing a second primary cancer, tissue confirmation should be obtained before they are given the diagnosis of metastatic disease. Lymph node involvement, metastases in the low neck, stage and extranodal extension (ENE) all increase the risk of developing distant metastases in patients with larynx cancer.33 A recent study found that ENE increases the risk of metastases tenfold.34

Diagnostic Evaluation

Initial Evaluation

The combination of information gleaned from cross-sectional imaging with clinical examination allows for the most accurate staging. CT scans with contrast enhancement and thin-cut slices through the larynx and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast are useful in the diagnostic imaging of laryngeal cancer. Both modalities are able to provide information that is essential in determining the appropriate treatment for a patient, including the presence or absence of disease in the pre-epiglottis, paraglottis, subglottis, cartilage invasion, extralaryngeal spread of disease, nodal metastases, and tumor volume. These studies are preferably performed before biopsy of the tumor, as postbiopsy edema may cause overestimation of tumor extent. Modern CT scanners provide high spatial resolution images that can be reformatted in any desired plane. The relative usefulness of CT scan versus MRI remains controversial, and in many cases the two modalities are complementary. The staging accuracy of MRI in laryngeal cancer is slightly higher, largely because of more accurate assessment of cartilage involvement and paraglottic and pre-epiglottic extension of tumor.35 MRI is more sensitive but less specific than CT in detecting cartilage invasion.36 With CT scans, correct T classification is possible in 70% to 80% of cases, and N stage in about 80%.37 The limitations of CT include the subtle evaluation of tumor-induced cartilage and bone defects and the detection of superficial tumors. CT evaluation is much faster than MRI and substantially reduces motion artifacts attributable to breathing, swallowing, or coughing. CT is still more commonly used for initial staging because of practical advantages such as cost, speed, and availability.38 According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) practice guidelines, either study is suitable for staging (see www.nccn.org).

The role of positron-emission tomography (PET) in laryngeal cancer has been growing during the previous decade, and although some have advocated for its routine use in the initial workup, its use in this setting remains investigational.39–41 Given the limited spatial resolution of PET, it is unlikely that it will contribute significantly to assessing the T stage. The benefit of PET is more likely to be in the detection of occult nodal and distant metastases.42 In contrast, the value of PET in post-treatment followup is well established as a method of detecting early recurrences.43,44 Typically, patients who are suspected of having a recurrence because of symptoms or laryngoscopic findings require examination under anesthesia and biopsy. In more than 50% of cases, the biopsies are negative. A study from the Netherlands showed that PET can help distinguish between recurrent disease and post-treatment changes.45 There is an ongoing randomized trial in the Netherlands investigating whether PET can accurately identify patients who require biopsy.46 PET also has a role in the evaluation of the neck after chemoradiation for locally advanced disease and may be able to select patients who do not require a neck dissection.47

Metastatic Workup

To complete the staging workup, imaging of the chest is recommended. A chest x-ray may be sufficient for patients with early stage disease at low risk for pulmonary metastasis. For patients with locally advanced disease at higher risk of metastases, a CT of the chest and possibly the entire torso is advisable. In addition, PET has been gaining popularity in detecting metastatic disease and there is data to suggest that PET can improve the detection of metastatic disease in a percentage of patients with locally advanced disease.42,48

Other Studies

Pulmonary function tests are performed in patients being considered for supraglottic laryngectomy or partial laryngopharyngectomy. Bronchoscopy and esophagoscopy are performed to rule out synchronous tumors. In addition, dental, speech, and swallowing evaluations are often advised. Routine laboratory tests include a complete blood count and liver function tests. If the liver function tests or serum alkaline phosphatase is abnormal, further studies such as liver and bone scans may be indicated. Attention should be given to the hemoglobin level as anemia may be a negative prognostic factor for patients with larynx cancer who receive radiation.49–52

Staging

The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system of the 2002 American Joint Committee on Cancer for carcinoma of the larynx is shown in Table 31-1.53 Primary tumor (T) classification is based on the extent of involvement within the larynx, extralaryngeal extension, cartilage invasion, and mobility of the vocal cords. In the past, any involvement of the thyroid cartilage was considered T4 disease, but based on the results of the Veterans Affairs (VA) Larynx Trial, minor thyroid cartilage erosion (inner cortex only) is now considered T3 for both glottic and supraglottic tumors. There must be invasion through the thyroid cartilage to be upstaged to T4. T4 lesions have been divided into T4a, or resectable disease, and T4b, or unresectable disease, leading to the division of stage IV into IVA and IVB. Regional lymph node (N) classification is based on size and number, as well as on ipsilateral, bilateral, or contralateral lymph node involvement. T stage is the most important prognostic factor in determining local control and N stage is an important prognostic factor for predicting distant metastasis and survival.

Therapeutic Approaches

Verrucous Carcinoma

Treatment of verrucous carcinoma of the vocal cords has been controversial. Bona fide cases of verrucous carcinoma do not metastasize and are associated with an excellent rate of control. Some have reported that these lesions have limited radioresponsiveness, and anaplastic transformation has been reported to occur after radiation therapy (RT).54–56 However, others have found that RT is quite effective and that anaplastic transformation rarely occurs.56,57 A recent study from Princess Margaret Hospital (PMH) showed that among 62 patients with verrucous carcinoma, none had anaplastic transformation after undergoing radiation.58 However, approximately one third of patients had a local failure after radiation requiring salvage surgery. Nearly all patients can be salvaged successfully, resulting in a 5-year disease-specific survival of 97%. The ultimate rate of larynx preservation in this series was 80%. Treatment for this rare lesion should be based on the extent of the disease. Small tumors can be treated by excision or partial laryngectomy. RT is recommended for large tumors that require total laryngectomy, with surgery reserved for salvage. For more aggressive tumors, concurrent chemotherapy can be considered.59

Carcinoma In Situ

CIS can be treated successfully with surgery or RT. Treatment practices range from observation after biopsy, to surgery (vocal cord stripping, cordectomy, laser excision, open-partial laryngectomy [OPL]), to primary radiation.60–68 Approximately two thirds of patients who pursue a watchful waiting approach develop invasive cancer, and some may no longer be candidates for larynx preserving therapy. Therefore, observation should be used with caution.67,69 Repeated biopsies, strippings, or laser excisions can lead to reduction of voice quality and should be avoided.

RT is an effective treatment modality for CIS of the larynx and there is a slightly higher rate of local control with RT than with vocal cord stripping or laser excision.61 The local control rate with primary RT ranges from 70% to 100% (average 87%). In contrast, the local control rate for laser resections and vocal cord stripping is 83% and 72%, respectively. A 5-year recurrence-free rate of 83% was reported by Elman and associates in a group of 69 patients with CIS of the vocal cords treated with RT.66 Spayne and associates reported the PMH experience of 67 patients treated with moderate-dose RT of 51 Gy in 20 daily fractions for 4 weeks. With a median follow-up of 6.5 years, the 5-year actuarial local control rate was 98%; only one patient developed invasive glottic cancer and eventually underwent salvage laryngectomy.68 A series from the University of Florida showed a 5-year actuarial local control rate of 88% after RT and 100% with salvage surgery.61 For well-defined lesions, stripping or laser resection are reasonable upfront options. For patients who recur, radiation should be considered. Also, for patients with more diffuse lesions or those not suitable for a limited surgical procedure, radiation should be offered. Patients who are not reliable for follow-up should receive radiation. Although doses of less than 60 Gy are often effective for CIS, many prefer to use more than 60 Gy because up to one third of patients have unrecognized invasive disease.69–71

T1 Glottic Carcinoma

The treatment objective for early invasive carcinoma of the larynx is to obtain cure with laryngeal preservation and optimal voice quality with minimal morbidity, expense, and inconvenience. Early stage cancers can effectively be treated with surgery or radiation. All patients should initially be treated with larynx preserving approach. Treatment guidelines emphasize that every effort should be made to avoid combining surgery and radiation because functional outcomes may be compromised. The treatment of choice, however, remains controversial. There is no one modality that has proven superior with regard to all treatment goals.72–78 There are no randomized trials comparing surgery and radiation for the treatment of early stage larynx cancer, and it is unlikely that such a trial will be conducted. A Cochrane review tried to compare the effectiveness of RT and surgery in early laryngeal cancer, but concluded ultimately that there was insufficient evidence to establish one modality as superior to the other.79 Conclusions regarding management must be based on a comparison of nonrandomized studies, and both modalities are currently accepted as standard treatment options.80 Larynx-preserving surgical procedures for early glottic cancers include endoscopic stripping, cordectomy, laser excision, and OPL, but some early stage tumors are not anatomically suitable for these limited surgeries. Selection of a treatment modality for an individual patient depends on a number of factors: location and extent of the tumor, vocal cord mobility, tumor growth characteristics, histology, general medical condition of the patient, occupation, patient compliance, patient preference, cost, availability, and preference of the treating surgical and radiation oncologists. Treatment philosophy varies significantly with geography and institution.81,82 RT is delivered primarily with external-beam irradiation and there is no routine role for brachytherapy in the management of larynx cancer. Patients with medical contraindications or patients who refuse surgery should receive RT. Patients who are not reliable for close follow-up may benefit from upfront surgery.

In general, for T1-N0 lesions, the rates of local control, laryngeal voice preservation, ultimate local control, and survival are comparable for patients treated with transoral laser excision, OPL, and RT. For patients with well-defined, superficial lesions involving one vocal cord, upfront laser resection can be considered. More extensive lesions involving the anterior commissure and both vocal cords have decreased local control after laser resection and upfront radiation is preferred. OPL carries higher morbidity and should be reserved for patients not eligible for either laser resection or RT. Although RT and laser resection offer similar cure rates for most T1 glottic tumors, voice quality is usually better after RT than after surgery, but this issue remains controversial as the literature is not conclusive.83–89 Local control after initial endoscopic resections is lower compared with radiation but local control is similar after salvage therapy.73 For patients whose occupation requires a high-quality, intact voice, RT may be the preferred initial treatment. If RT fails, salvage surgery is successful in 75% to 85% of the patients in whom surgery is attempted. In the past, most patients who failed primary radiation required laryngectomy, but, as the experience with larynx-preserving surgery has grown, up to 50% of patients in the recurrent setting can undergo larynx preserving salvage surgery.90–94

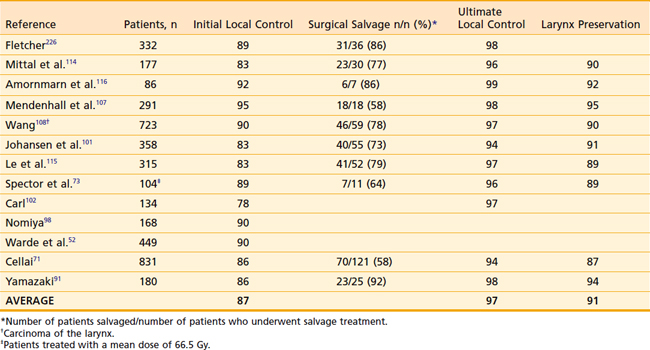

Results of primary RT for T1 carcinoma of the glottis are shown in Table 31-2 and Table 31-3. For T1 lesions, the initial local control rates are in the range of 78% to 95%, and the ultimate local control rates after surgical salvage of failures are in the range of 94% to 99%. The larynx is preserved in 89% to 95% of the irradiated patients. A number of investigators have shown that total treatment time and dose and fraction size can affect local control.95–98 In addition, anterior commissure involvement, subglottic extension, beam type and energy, field size, gender, histologic grade, pretreatment hemoglobin, and total dose may all influence local control rates.52,71,73,95,96,99–103 Higher doses may only be needed for more extensive T1 lesions.73,98 A recent study from Italy found that male gender, greater tumor extent, anterior commissure involvement, and use of electrons or cobalt all were independent predictors on multivariate analysis for local failure.71 Tumor response at 3 to 6 weeks after completion of radiation also significantly affects local control.102

Table 31-3 Stage T1 Carcinoma of the Glottis: Survival After Radiotherapy and Surgical Salvage

| Reference | Patients, n | 5-Yr Survival, % |

|---|---|---|

| Mittal et al.114 | 177 | 97 (determinate) |

| Amornmarn et al.116 | 86 | 96 (determinate disease-free) |

| Mendenhall et al.107 | 291 | |

| Johansen et al.101 | 358 | 94 (determinate) |

| Le et al.115 | 315 | |

| Spector et al.73 | 104 | |

| Nomiya98 | 169 | |

| Cellai et al.71 | 831 | |

| Yamazaki et al.91 | 180 |

A randomized trial from Japan compared 2 Gy per fraction versus 2.25 Gy per fraction in the treatment of stage 1 glottic cancer.91 In this study, smaller tumors received a slightly lower dose (56.25 Gy in 2.25 Gy fractions or 60 Gy in 2 Gy fractions) than larger tumors (63 Gy in 2.25 Gy fractions or 66 Gy in 2 Gy fractions). Larger fraction size increased local control from 77% to 92%, corroborating the previously published retrospective series that suggested that larger fraction size improves local control. On multivariate analysis, treatment arm was the only significant independent prognostic factor with an odds ratio of 3.38. This study established hypofractionation with 2.25 Gy as a standard fractionation for T1-N0 glottic cancer. At our institution, we treat T1 glottic tumors to 63 Gy in 2.25 Gy fractions regardless of size.

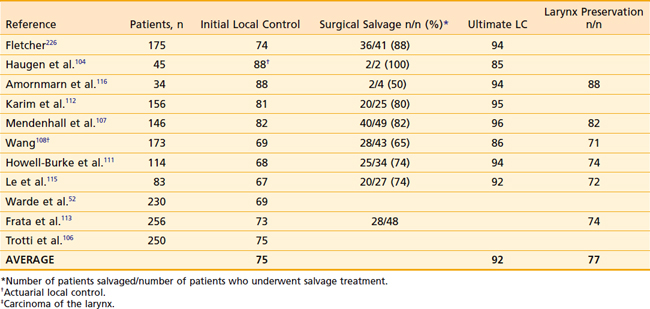

T2 Glottic Carcinoma

For T2 carcinoma of the glottis treated with primary RT, the initial local control rates are in the range of 67% to 88%. After surgical salvage, the ultimate local control rates are in the range of 85% to 96%. The larynx is preserved in 71% to 88% of the patients irradiated. Results of primary RT for T2 carcinoma of the glottis are shown in Table 31-4 and Table 31-5. Several studies have shown that local control improves with hyper- or hypofractionated radiation.104,105 Garden and colleagues showed that more than 2 Gy per day improved local control whether it was delivered as more than 2 Gy per daily fraction or more than 2 Gy in smaller, twice-daily fractions. This study led to a phase-III Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trial comparing 79.2 Gy in 66 fractions of 1.2 Gy twice-daily fractions to 70 Gy in 35 fractions of 2 Gy daily.106 Preliminary results presented in abstract form showed a nonsignificant improvement from 70% to 79% in local control with hyperfractionation. The outcomes with hypofractionation and hyperfractionation both appear to be superior to conventional fractionation.105,107 Thus the debate regarding the optimal fractionation regimen is ongoing, but it is generally agreed that either hyperfractionation or hypofractionation regimens are favored over conventional fractionation. At Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), we typically treat T2-N0 glottic tumors to 65.25 Gy in 2.25 Gy fractions.

Table 31-5 Stage T2 Carcinoma of the Glottis: Survival After Radiotherapy and Surgical Salvage

| Reference | Patients, n | 5-Yr Survival, % |

|---|---|---|

| Amornmarn et al.116 | 34 | 88 (determinate disease-free) |

| Karim et al.112 | 156 | |

| Mendenhall et al.107 | 228 | |

| Howell-Burke et al.111 | 114 | |

| Le et al.115 | 83 | 78 (actuarial) |

| Frata et al.113 | 256 | |

| Trotti106 | 250 | 68 (absolute) |

Impaired vocal cord mobility and anterior commissure involvement may be associated with lower local control rate and survival in some series, but the data are inconclusive.28,62,96,97,108–114 Subglottic extension, poorly differentiated histopathology, and male gender have been associated with poorer results in some series.105,108,110,115–117 Paraglottic extension is likely associated with increased tumor volume but, by itself, is not associated with increased local failure.117 Others have noted no significant difference in the outcomes with respect to subglottic extension, gender, or differentiation.111,114

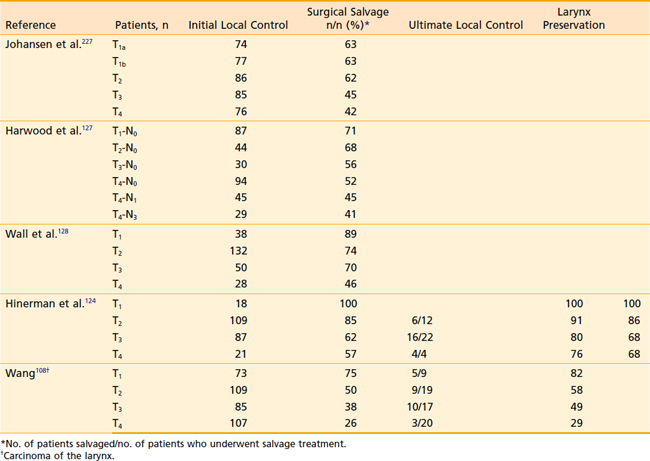

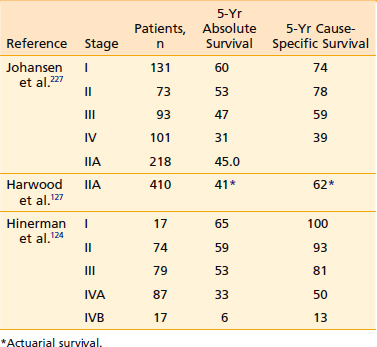

Early Supraglottic Carcinoma

The prognosis for early stage supraglottic cancer is slightly worse than for early glottic cancer. Results of primary RT for supraglottic tumors are shown in Table 31-6 and Table 31-7. As is the case for early stage glottic cancer, all patients with early stage supraglottic larynx cancer should be treated with the intent to preserve the larynx. However, the optimal treatment modality for these tumors is still debated. For early stage, favorable lesions, endoscopic laser resection, open-partial supraglottic laryngectomy, and radiation are all considered standard treatment options. Careful patient selection is critical, as only some patients will be candidates for larynx-preserving surgery because of either tumor location or extent or because of comorbidities. Local control after upfront partial laryngectomy is likely slightly higher than with upfront radiation, but more than 50% of patients will not be candidates for OPL because of comorbid conditions or location and extent of the tumor. Direct comparisons of the two treatment modalities are complicated by the fact that many patients undergoing partial laryngectomy subsequently receive adjuvant RT. Surgical candidates tend to be younger and healthier, further confounding comparisons. In addition, surgical series often use surgical staging, leading a portion of the patients to be upstaged. Supraglottic laryngectomy is contraindicated when there is arytenoid fixation, bilateral arytenoid involvement, involvement of the apex of the pyriform sinus, invasion of the thyroid or cricoid cartilage, involvement of the postcricoid region, impaired vocal cord mobility, extension into the glottic area, and extensive involvement of the base of the tongue. Orus and colleagues showed slightly better initial local control with partial laryngectomy compared with radiation but, with salvage surgery, both resulted in ultimate local control of 90% for T1– and T2-N0 supraglottic tumors.118

Because of the potential morbidity associated with OPL, there has been a growing interest in the treatment of early supraglottic cancer with transoral endoscopic resection. There is emerging data that transoral laser excision in well-selected patients may be equal in outcome to traditional OPL and carries less morbidity.119–123 Table 31-8 and Table 31-9 show a summary of the published literature on the outcomes of laser excision of early stage larynx cancer. Laser partial laryngectomy reduces time required to restore swallowing, tracheostomy rates, aspiration pneumonia rates, and fistula formation, and shortens hospital stays. Preliminary outcomes are encouraging, but more experience is needed with this technique before it can be considered standard therapy.80

Table 31-8 Stage 1 Carcinoma of the Supraglottis: Local Control With Laser Resection

| Reference | Patients, n | Initial LC |

|---|---|---|

| Eckel228 | 9 | 89 |

| Iro et al.229 | 39 | 79 |

| Ambrosch et al.230 | 12 | 100 |

| Rudert et al.231 | 4 | 100 |

| Zeitels et al.232 | 13 | 88 |

LC, Local control.

Table 31-9 Stage 1 Carcinoma of the Supraglottis: Local Control With Laser Resection

| Reference | Patients, n | Initial LC |

|---|---|---|

| Eckel228 | 26 | 92 |

| Iro et al.229 | 54 | 87 |

| Ambrosch et al.230 | 34 | 88 |

| Rudert et al.231 | 10 | 80 |

| Zeitels et al.232 | 6 | 100 |

| Davis et al.233 | 8 | 100 |

LC, Local control.

A large series from Florida showed that 5-year actuarial probability of local control after RT for T1 and T2 supraglottic tumors was 100% and 86%, respectively.124 This cohort included a large percentage of patients who would not be eligible for partial laryngectomy. Other radiation series report similar outcomes. Carl and colleagues showed that tumor grade, size, and patient sex were independent prognostic factors.102 A retrospective series from the United Kingdom for T1 and T2 supraglottic cancers treated with larynx-preserving surgery or standard fractionated radiation showed that control of the primary tumor was equivalent between the two modalities.84 Tumor size has been shown to be a poor prognostic factor in patients receiving radiation. Several studies have shown that large tumors of more than 6 to 8 cm3 on CT have much higher rates of recurrence after radiation.124–126 The presence of lymphadenopathy, especially with lymph nodes greater than 3 cm in diameter, may have an adverse effect on local control as well as survival.127,128 However, Freeman and colleagues found that local control depended on T classification and was not influenced by N stage.129

Locally Advanced Larynx Cancer

Locally advanced glottic and supraglottic larynx cancers (stages III and IV) are treated similarly for the most part and are discussed together. The outcome for patients with advanced disease is much worse than for early stage, which has long-term survival rates ranging from 30% to 60%.130,131 The standard treatment for many years of locally advanced, resectable larynx cancer was laryngectomy and postoperative radiation for surgical candidates and radiation alone for medically inoperable patients. Laryngectomy is widely recognized as one of the most feared surgical procedures by patients. In fact, studies on patient preferences showed that 25% of individuals would be willing to trade a 20% absolute difference in survival for the opportunity to save their voice. As a result of two important randomized trials, there has been a major paradigm shift during the previous two decades for most patients to concurrent chemoradiation. Total laryngectomy should be reserved for patients with T4 lesions with extensive cartilage involvement or as salvage treatment for local failures or nonresponders to chemoradiation. For select T3 and T4 lesions, amenable to larynx-preserving surgery, a conservative surgical approach is an acceptable alternative to chemoradiation. However, postoperative radiation is often needed and voice quality in these cases can be low. Patients with unresectable larynx cancer should also receive concurrent chemoradiation because results with radiation alone are suboptimal.132,133 Primary surgery and concurrent chemoradiation have not been compared exclusively in larynx cancer, but a trial from Singapore compared these two modalities for all SCC of the head and neck (sinonasal and nasopharynx excluded) and found no difference in 3-year disease-free survival. In addition, this study found that larynx preservation was higher for larynx and hypopharynx cancers than other tumor subsites.

Select patients with more favorable Stage III-IV disease or those who are not candidates for chemotherapy, can be treated with definitive radiation alone. These patients should receive altered fractionation regimens. Retrospective comparisons suggest a higher local-regional control rate with hyperfractionated or accelerated hyperfractionated RT.108,134,135 A phase-III RTOG randomized trial showed that hyperfractionation and accelerated fractionation with concomitant boost are more efficacious than standard fractionation for locally advanced head and neck cancer in terms of local control and disease-free survival.136 Whether there is a benefit to using altered fractionation with concurrent chemoradiation is currently being evaluated by the RTOG.

The first trial to demonstrate the feasibility of larynx preservation was the VA Laryngeal Cancer Study.130

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree