Cancer of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus often present significant challenges in management, owing to the critical role these anatomical sites play in the normal function of the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT). The structural proximity, close physiologic coordination, and similarity in oncologic aspects allow concurrent discussion of cancer arising from the two sites. Treatment of cancer of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus includes the use of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy in different combinations depending upon the stage of the cancer. With a growing emphasis on organ preservation, the selection of therapeutic option, surgical or nonsurgical, which maximally controls disease and preserves function, remains critical. This chapter focuses on the approaches to the management of cancers of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus with relevant anatomic, pathologic, and etiologic details.

SURGICAL ANATOMY

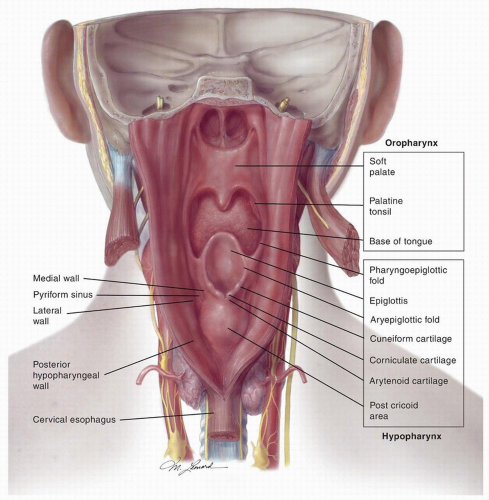

The hypopharynx extends from its junction with the oropharynx at the level of the tip of the epiglottis to its junction with the cervical esophagus inferiorly

(Fig. 16.1). The bony landmarks are the hyoid superiorly, the lower border of the cricoid cartilage inferiorly, and C3 to C6 vertebrae posteriorly. The hypopharynx is comprised of three anatomical subsites—the pyriform sinus (PFS), the postcricoid area, and the posterior pharyngeal wall. These three subsites are continuous with one another and cancers often involve more than one subsite.

The PFS is a conical structure located on each side of the hypopharynx that extends from the pharyngoepiglottic fold down to its inferior-most extent, the apex, which opens medially into the cervical esophagus. The superior part of the PFS is bounded by the thyrohyoid membrane and thyroid cartilage laterally and the aryepiglottic fold (AEF) and arytenoid cartilage medially. The apex of the PFS is bounded by the thyroid cartilage laterally and by the cricoid cartilage medially. The medial wall of the PFS is separated from the endolarynx by the AEFs.

The postcricoid area extends from the level of the arytenoid cartilages to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage at the pharyngoesophageal junction. It lies in close proximity to the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles and the medial wall and apices of the PFSs.

The posterior wall of the hypopharynx extends from the level of the tip of the epiglottis (or the floor of the vallecula) to the level of the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage. The superior and inferior boundaries of the posterior wall of the hypopharynx merge with the walls of the oropharynx and the esophagus, respectively, whereas the lateral boundaries are continuous with the PFS. The mucosal lining of the wall of the hypopharynx is separated from the prevertebral space by a fibrous layer formed by the pharyngeal aponeurosis; a muscular layer formed by the middle and inferior constrictors; the buccopharyngeal fascia; the retropharyngeal space; and the prevertebral fascia. The distal-most fibers of the inferior constrictor muscles form the cricopharyngeus muscle, which constitutes the primary muscle of the upper esophageal sphincter and marks the junction between the postcricoid area and the cervical esophagus.

The cervical esophagus lies posterior to the trachea and thyroid gland, extending from the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage (opposite C6 vertebra) to the level of the thoracic inlet (opposite T1 vertebra). It deviates to the left in the inferior aspect of the neck and is medial to the common carotid artery and recurrent laryngeal nerve on either side and the thoracic duct on the left. The esophageal wall from inside out is made up of a mucosal, submucosal, muscular, and an external fibrous layer. The muscular layer consists of internal circular fibers, which are continuous with the cricopharyngeus muscle, and external longitudinal fibers that are covered with a fibrous layer in continuity with the wall of the hypopharynx.

Nerve supply: The pharyngeal constrictor muscles receive motor innervation through the pharyngeal plexus with additional innervation of the inferior constrictors from branches of the external laryngeal and the recurrent laryngeal nerves. The recurrent laryngeal nerve provides motor innervation to the cricopharyngeus and the posterior cricoarytenoid muscles, whereas the sensory innervation of the hypopharynx is derived primarily from the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. This branch synapses with a branch of the vagus, Arnold’s nerve, which provides sensation to the external auditory canal and which accounts for the symptom of referred otalgia from cancer of the hypopharynx. Additional sensory innervation is also provided by branches of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Innervation to the cervical esophagus is derived from the recurrent laryngeal nerve and sympathetic chain.

Vascular supply: The superior laryngeal branch of the superior thyroid artery is the primary blood supply to the superior aspect of the hypopharynx; the inferior part is supplied by the inferior laryngeal branch of the inferior thyroid artery. The vascular supply of the cervical esophagus is derived primarily from the inferior thyroid artery. Venous drainage from the hypopharynx occurs through the submucosal pharyngeal venous plexus, which drains into the internal jugular vein, whereas the cervical esophagus drains into the inferior thyroid vein.

Lymphatic drainage: The hypopharynx is rich in lymphatics, which pierce the thyrohyoid membrane to drain into the deep jugular chain (level II, III, and IV) nodes. Lymphatics from the inferior aspect of the PFS and the postcricoid area pierce the cricothyroid

membrane and drain into the paratracheal chain (level VI) nodes. From the posterior pharyngeal wall, drainage occurs into the retropharyngeal nodes (RPLNs) including the nodes of Rouviere superiorly. Lymphatics from the cervical esophagus usually drain first into the paratracheal and paraesophageal nodes, and second, into the cervical and superior mediastinal nodes.

PATTERNS OF SPREAD

Cancers from the medial wall of the PFS spread medially to the endolarynx by invading the AEF or the paraglottic space causing fixation of the hemilarynx. Posterior extension into the postcricoid area can lead to infiltration into the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle with fixation of the ipsilateral vocal cord. Infrequently, fixation of the hemilarynx can also result from the direct invasion of the cricoarytenoid joint or the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Anterior and lateral spread leads to involvement of the lateral wall of the PFS and/or the wall of the hypopharynx. From the lateral wall of the PFS, cancer can extend into the cervical soft tissues to involve the strap muscles, thyroid gland, and other extralaryngeal structures through direct invasion of the thyroid cartilage or by spread around the posterior border of the thyroid cartilage at the insertion of the inferior constrictor muscles. Posterior extension involves the posterior wall of the hypopharynx, whereas the lateral wall of the oropharynx, pharyngoepiglottic fold, and the base of the tongue can be involved by superior extension.

Cancers reaching the apex of the PFS can involve directly the postcricoid area and the cricoid cartilage. Cancers of the postcricoid area can extend directly to the cricoid cartilage and the trachea and, submucosally, toward the cervical esophagus. Submucosal spread of cancer superiorly to the oropharynx and inferiorly to the esophagus can also occur from the posterior wall of the hypopharynx. Cancers from this site can involve the pharyngeal constrictors and the buccopharyngeal fascia. The fascia is a weak barrier, and further posterior spread can involve the prevertebral fascia and the prevertebral musculature, ultimately reaching the periosteum of the vertebral column.

Cancers of the cervical esophagus can spread anteriorly to the trachea, laterally to the tracheoesophageal groove and recurrent laryngeal nerve(s), and posteriorly to the prevertebral space.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cancer of the hypopharynx is rare and accounts for 3% to 5% of the malignancies in the UADT.

1 The American Cancer Society estimates 3,400 cases in 2014, ˜2,725 in men and 675 in women. The worldwide age-standardized incidence estimated by GLOBOCAN 2012 report from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) is 1.9 per 100,000 and a total number of 142,387 new cases.

2 The precise incidence for either the hypopharynx or the individual hypopharyngeal subsites is, however, difficult to estimate due to the combined reporting on all cancers of the pharynx by the IARC. In addition, a marked gender and geographical variation is known to exist, with a higher incidence in males and in certain regions of Central and Eastern Europe, France, and Southeast Asia.

Cancer of the PFS and posterior hypopharyngeal wall occurs predominantly in males, aged 55 to 70 years, and is strongly associated with excessive alcohol consumption and smoking. Carcinoma of the postcricoid area is more common in females, aged 30 to 50, with underlying nutritional factors such as Plummer-Vinson syndrome as a possible etiology. It is mainly reported from Sweden and other Scandinavian nations; however, improved nutrition has been shown to decrease the incidence of Plummer-Vinson syndrome and, therefore, the incidence of postcricoid carcinoma from these regions.

3,4 Chronic gastroesophageal reflux and human papillomaviruses are postulated to have an etiologic association to cancer of the hypopharynx in nonsmokers and nondrinkers.

5 Genetic predisposition and occupational exposure to carcinogens such as solvents, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, sulfuric acid, asbestos, welding fumes, wood dust, nickel, and leather have also been implicated as etiologic factors.

3Cancers involving the cervical esophagus make up 2% to 10% of all cancers of the esophagus and are derived from the caudal extension of cancers originating in the hypopharynx.

6,7 Cervical esophageal cancer is predominantly seen in males and has a high incidence in certain regions of Iran, Central Asia, Mongolia, and Northern China. The risk factors for the development of cancer of the cervical esophagus are similar to those for the hypopharynx. Prolonged irritation from thermal injury or corrosives such as lye is also associated with increased risk.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Approximately 95% of the cancers of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus are squamous cell carcinomas (SCC). Invasive SCC may be preceded by premalignant lesions. The PFS is the most common site of involvement, accounting for 65% to 85% of the hypopharyngeal SCC, followed by the posterior wall of the hypopharynx (10% to 20%) and the postcricoid area (5% to 15%). Submucosal spread and skip lesions are an important characteristic of cancers arising from these sites; spread of 5 to 30 mm beyond macroscopically visible cancer has been observed.

8 Whereas cancers of the PFS and posterior pharyngeal wall are more frequently exophytic, postcricoid cancers are more commonly ulcerative. Basaloid carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, and spindle cell carcinoma are rare SCC variants characterized by more aggressive behaviors.

9 Spindle cell carcinoma occurs mostly in patients with a history of prior radiation that typically presents as a polypoid mass projecting into the pharyngeal lumen.

10 The hypopharynx and cervical esophagus can also give rise to malignant nonsquamous tumors such as, (1) minor salivary gland adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma; (2) sarcomatous lesions such as fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and synovial cell sarcoma; (3) reticuloendothelial tumors such as lymphoma and plasmacytoma; and (4) melanoma.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND EVALUATION

Presenting Symptoms and History

The common presenting symptoms, which suggest cancers originating from the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus, are progressive dysphagia, odynophagia, sore throat, referred otalgia, weight loss, and/or a mass in the neck. These cancers usually present at an advanced stage because the nonspecific symptoms of minor irritative sensation or sore throat from early-stage cancer may be too easily dismissed. Aspiration, hemoptysis, and weight loss occur with advanced cancer. Persistent pain in the throat with referred otalgia may be indicative of perineural invasion. Hoarseness and breathing difficulty are indicative of laryngeal involvement. Metastases to the cervical lymph nodes are known to occur in 50% to 80% of the patients at presentation, and not infrequently, patients may present with only a metastatic mass in the neck in the absence of any of the aforementioned symptoms related to the primary cancer.

1,13 A thorough history should be elicited about prior risk factors including alcohol and smoking habits, laryngopharyngeal or gastroesophageal reflux, nutritional status, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, and occupational exposures; past treatments such as radiation and/or chemotherapy; and general medical condition including coexisting pulmonary or cardiovascular comorbidities.

Imaging

Radiologic studies such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are performed to complete the diagnostic evaluation. Compared to CT, MRI is more susceptible to motion artifacts from swallowing, coughing, or any other movement and is usually the second line of investigation; it may however be preferred to assess cancers that recur after resection or chemoradiation for better tissue delineation.

3 Radiology complements physical examination with information about the inferior extent of cancer, submucosal spread, invasion of the thyroid cartilage, and extralaryngeal involvement. Involvement of the prevertebral fascia or space should be ruled out for the primary cancers arising from or extending to the posterior wall of the pharynx. Imaging can also reveal the presence of a synchronous primary cancer, which is known to have a high incidence in the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus due to

field cancerization effects from chemical carcinogens. Barium swallow is helpful in ruling out an esophageal cancer. It also facilitates diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders in patients with progressive dysphagia with no risk factors for SCC and a normal physical examination. Endoscopic ultrasonography is considered to be a more accurate imaging technique in determining the T stage of cancers of the cervical esophagus.

Ultrasonography and CT are of help in an accurate search for lymph node metastases; the latter is superior in demonstrating RPLN metastases. High rates of distant metastases of 10% to 30%

1,14,15 are associated with cancers of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus. Hence, screening with whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) or chest and abdominal CT scans is recommended, particularly in patients with prolonged symptoms and bulky lymph node metastases.

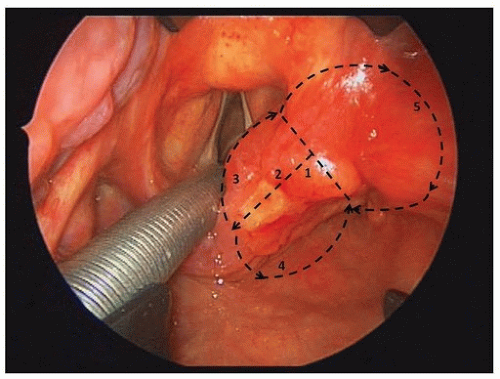

Endoscopy Under Anesthesia and Biopsy

Examination under anesthesia (EUA) of the pharynx, larynx, trachea, and esophagus under anesthesia with rigid endoscopes is fundamental to accurately evaluate the cancer site and stage and detect synchronous primary cancer of the UADT. A rigid esophagoscopy is required to assess spread of the cancer to the cervical esophagus and to rule out a synchronous esophageal primary cancer. EUA allows tissue biopsy for diagnostic confirmation, although a histologic diagnosis can be achieved with fine-needle aspiration in patients with palpable neck nodes. In patients with advanced cancers and widely scattered foci of dysplastic-appearing mucosa in the UADT, mapping biopsies are a useful aid to predict resectability. Mapping biopsies are also important for chemoradiation-recurrent cancers; many of these cancers do not exhibit typical clinical or radiologic findings, and malignant tissues may lurk beneath intact mucosa far distant from the epicenter of the primary cancer. Palpation of the cancer and movement of the cancer over the prevertebral fascia help to ascertain fixation for cancer of the posterior wall of the hypopharynx. Bronchoscopy is recommended for patients with cancer of the cervical esophagus in order to detect anterior extension of the cancer or a synchronous primary cancer. Based on information from clinical, radiologic, and endoscopic evaluations, a final clinical tumor stage (cT) is determined

(Table 16.1) according to the American Joint Commission Cancer (AJCC) staging system. EUA for cancer of the hypopharynx also gives an opportunity to determine the access and feasibility for resection via a transoral approach. In cases unsuitable for transoral resection, assessment is directed toward decision-making for conservation versus radical surgical approaches and/or nonsurgical management. Assessment of the extent of the anticipated pharyngeal defect from surgical resection, as well as the most appropriate type of reconstruction, should be made during EUA. For patients likely to undergo a flap reconstruction, a donor site and potential alternatives should be planned.

Additional Investigations

Routine hematologic and blood chemistry investigations are performed as part of pretreatment evaluation. Assessment of iron deficiency is particularly relevant in females with features of Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Protein deficiency and overall nutritional status should also be evaluated, and corrective measures initiated prior to initiation of treatment. The cachectic patient may benefit from pretreatment insertion of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. A majority of patients are heavy smokers; hence, pulmonary reserve is checked with careful history and pulmonary function tests, and referrals to tobacco cessation programs are made. Patients with poor pulmonary reserve may not be candidates for transoral or open conservation surgery due to the high risk of developing pulmonary complications from postoperative aspiration. Assessment of dentition is done during office examination, and referral is made to a specialist if restorative procedures or dental extractions are required, particularly for patients who are planned to receive radiation as part of the treatment.