40 Cancer of the Colon

Epidemiology, Etiology, Genetics, and Cytogenetic Abnormalities

Epidemiology

In 2007, there will be an estimated 112,340 new cases of colon cancer in the United States, with 55,290 occurring in men and 57,050 occurring in women. Approximately 52,180 deaths are expected.1 The median age at diagnosis is 62 years. Patients under 40 years have a less favorable prognosis. However, it is unclear if this is independent of stage.

It has been postulated that colorectal cancer is caused or promoted by environmental factors and especially by dietary factors that affect the enteric milieu.2 A number of studies reveal an association of human colorectal cancer with certain diets (such as those rich in animal fats and meat and poor in fiber) and certain high-risk populations.3

In general, the traditional Western diet (high fat, low fiber, high phosphate, and low calcium) is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. However, there have not been any clear studies demonstrating whether dietary factors increase the risk in patients with an underlying genetic susceptibility. There are a variety of risk factors for colorectal cancer (Table 40-1). Approximately 75% of colorectal cancers are sporadic.

Table 40-1 Clinical Risk Factors for Colorectal Cancer

| General |

| Age older than 40 |

| Genetic syndromes |

| Peutz-Jeghers |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis |

| Gardner’s |

| Turcot’s |

| Oldfield’s |

| Familial |

| Family history |

| Lynch I: Familial colorectal cancer syndrome |

| Lynch II: Hereditary adenocarcinomatosis syndrome |

| Other diseases |

| Prior colorectal cancer |

| Malignant colorectal polyps |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

Molecular Genetics

Only recently has the genetic basis of colorectal cancer and its precursors begun to be understood.4,5 The data suggest that the development of colorectal cancer is a multistep process that involves a successive activation or deletion of genes and their protein products.6 This process is mediated by regulatory genes. Advances in molecular biology techniques have allowed characterization of the genetic changes thought to be responsible for this multistep process.7

Numerous molecular markers examined to date, such as microsatellite instability (MSI),8 18q,9 TP53,10 and others such as proliferation, apoptosis, defective DNA mismatch repair, and p53 overexpression.11 However, they are not currently incorporated in the staging system and T and N classification remain the most predictive factors. But this is rapidly changing, and US intergroup trials now prospectively collect tissue. The phase III ECOG 5202 trial for patients with high-risk stage II colon cancer assigns treatment based on MSI/18q status. In the near future, more-individualized therapeutic recommendations based on genetic markers may be possible.12

Anatomy

The large bowel is divided into the colon and rectum.13,14 The cecum, transverse colon, and sigmoid loop are mobile structures that lie free in the peritoneal cavity and are completely covered with serosa (visceral peritoneum). The dorsal or posterior aspect of the ascending and descending colon, and both flexures are frequently without serosa. Tumor spread from these segments may involve the retroperitoneal soft tissues, kidney, ureter, and pancreas. Although the rectum is frequently considered to be extraperitoneal, the anterior surface of the proximal third of the rectum is covered with serosa and is therefore intraperitoneal. Anatomically, the transition from sigmoid colon to rectum is marked by the fusion of the tenia of the sigmoid colon to the circumferential longitudinal muscle of the rectum at the level of the sacral promontory. This occurs approximately 12 to 15 cm from the dentate line. Patterns of recurrence of proximal rectal cancer may depend upon whether the location of the tumor is anterior or posterior.

The overall rationale of the use of adjuvant radiation therapy in colon cancer is based on the patterns of failure following potentially curative surgery. The primary determinant of failure patterns in colorectal cancer is the location of the tumor in reference to the posterior peritoneal reflection. In contrast to tumors located at or below the posterior peritoneal reflection (rectosigmoid and rectum), most tumors located above the peritoneal reflection (cecum-sigmoid), have a higher incidence of failure within the abdominal cavity.15–18 This is because colon tumors have easier access to a free peritoneal surface.

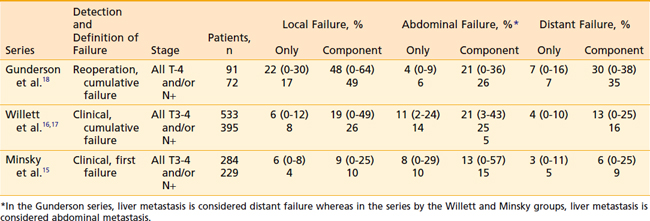

Representative series examining the patterns of failure after potentially curative surgery are seen in Table 40-2. There is much variation as to what defines failure, the method by which failure is determined, the staging system used, and whether patients with metastatic disease are excluded from analysis. Failure patterns will be lowest in series which use clinical and/or radiographic evidence of first failure,15 whereas they will be highest in series which use reoperation and/or autopsy evidence of cumulative failure.18

Pathology

Histologic Subtypes

The most common histologic type of large bowel cancer is adenocarcinoma, which accounts for 90% to 95% of all large bowel tumors.13 It is the only histologic type further classified by grade. A number of histologic types of large bowel cancer have been identified. The World Health Organization has developed a classification of both benign and malignant tumors. Colloid or mucinous adenocarcinoma represent approximately 17% of large bowel tumors.19 These adenocarcinomas are defined by large amounts of extracellular mucin retained within the tumor. A separate classification is the rare signet-ring cell carcinoma (2% to 4% of mucinous carcinomas), which contains abundant intracellular mucin, pushing the nucleus to one side. Some signet-ring tumors form a linitis plastica–type appearance, tend to present at later stages, and, thus, have a poor prognosis.20,21

Other rare variants of epithelial tumors include squamous cell carcinomas, adenosquamous carcinoma (adenoacanthoma), undifferentiated carcinomas, small cell,22 and neuroendocrine cancers.23 Gastrointestinal stromal tumors should be treated as sarcomas.24 Sarcomas account for 0.1 to 0.3% of all malignancies of the colorectum.25 The most common type is leiomyosarcoma. It may arise from the smooth muscle of the muscularis propria, muscularis mucosa, or blood vessels.26 Primary colorectal malignant lymphomas are usually diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.27 Squamous cell cancers of the rectum should be treated as an anal cancer with fluorouracil (5-FU)/mitomycin-C and radiation, reserving surgery for salvage.28

Grade

Broders classified adenocarcinomas by their degree of differentiation. He designated four grades based on the percentage of differentiated tumor cells. Well-differentiated in Broders’ system meant well-formed glands resembling an adenoma. Broders included the mucinous carcinomas in his system. Dukes considered mucinous carcinomas separately.29 There is no uniform agreement on the grading criteria, but most investigators agree on the use of a three-grade system similar to that described in other adenocarcinomas.

Other Clinicopathologic Factors

The influence of clinical and pathologic factors on the patterns of failure and survival following surgery colorectal cancer has been the subject of numerous investigations. By univariate analysis, a number of factors have been reported to be of prognostic importance. Many of these factors are interrelated and merely reflections of the same overall characteristic of the cancer. Using a multivariate (proportional hazards) analysis, a variety of independent factors for survival have been reported. However, the majority of investigators agree that the most important independent pathologic factor for survival and/or recurrence following surgery is stage (depth of penetration through the bowel wall and the presence and number of positive lymph nodes).30,31 Prognosis is related to the number of tumors rather than the volume of tumor present in the nodes.32 The presence of lymphatic vessel (L) or venous (V) invasion is now indicated as an additional descriptor in the TNM staging system.

Selected adverse clinical factors include: age <40 years, blood transfusions, long duration of symptoms, obstruction or perforation, ulceration, and various primary tumor locations. Selected adverse pathologic/molecular factors include: perineural invasion, high grade, colloid, signet ring cell, blood vessel invasion, lymphatic vessel invasion, aneuploidy, elevated carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels, collagen, local immune response, cell surface antigen 19-9, and various growth factors, receptors, oncogenes, and blood group antigens.13 Except for CEA, none of these tumor markers have independently been shown to be helpful in prospective follow-up following treatment.33

Routes of Spread

Lymph Nodes

The risk of lymph node metastases increases with increasing tumor grade. In addition, there is a clear relationship between lymphatic vessel invasion and the incidence and number of lymph node metastases in colorectal cancer.34,35 At least 12 to 14 lymph nodes must be examined for an accurate classification of nodal status.36,37 Although they may be confused with lymph nodes, pericolonic tumor deposits are a harbinger of intra-abdominal metastasis in colon cancer.38 In the sixth edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging System, smooth metastatic nodules in the pericolic or perirectal fat are considered lymph node metastasis, whereas irregularly contoured metastatic nodules in the fat are considered vascular invasion.39

In colon cancer, the normal lymphatic flow is through the lymphatic channels along the major arteries, with three echelons of lymph nodes: pericolic, intermediate, and principal lymph nodes (Table 40-3).13 If tumors lie between two major vascular pedicles, lymphatic flow may drain in either or both directions. If the central lymph nodes are blocked by tumor, lymphatic flow can become retrograde along the marginal arcades both proximally and distally.

Table 40-3 Regional Lymph Nodes in Colon Cancer

| Site | Regional Nodes |

|---|---|

| Cecum | Anterior and posterior cecal, ileocolic, right colic |

| Ascending colon | Ileocolic, right and middle colic |

| Hepatic flexure | Middle and right colic |

| Transverse colon | Middle colic |

| Splenic flexure | Middle and left colic, inferior mesenteric |

| Descending colon | Left colic, inferior mesenteric, sigmoid |

| Sigmoid loop | Inferior mesenteric, superior rectal (hemorrhoidal), sigmoid, sigmoid mesenteric |

In rectal cancer, the disease metastasizes to the perirectal nodes at the level of the primary tumor, immediately above it and up to 5 cm distal to the primary tumor.40,41 Then, the chain accompanying the superior hemorrhoidal vessels is involved. Discontinuous or skip metastases are rare. The pericolic lymph nodes along the mesenteric border of the pelvis usually are not involved by these rectal tumors unless there is very extensive tumor with lymphatic blockage.

Diagnostic and Staging Studies

The work-up for colon carcinoma is seen in Table 40-4. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scanning shows promise, but remains investigational.43,44 The staging of colorectal carcinoma has been complicated by the fact that it has evolved over a century and various authors have developed systems that use the same terms to represent different stages. Because of these discrepancies in coding for the same stages, the comparison of clinical studies reported in the literature is often impossible.

Table 40-4 Workup for Colon Cancer

The Astler-Coller staging system allowed separation of wall penetration and nodal status. The Gunderson-Sosin modification of the Astler-Coller staging system subdivided T3 tumors into those with microscopic (B2m or C2m) or gross (B2m+g or C2m+g) penetration of tumor through the bowel wall.45,18 It also defined tumors adherent to or invading an adjacent organ or structure as B3 if the nodes were negative and C3 if the nodes were positive. Several studies have analyzed both local failure and survival using the modified Astler-Coller staging system15,16,18,45–47 Most have confirmed the predictive capability of this staging system.

In 1988, the AJCC48 and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC)49

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree