42 Cancer of the Anal Canal

Epidemiology, Etiology, Genetics, and Cytogenetic Abnormalities

Cancers of the anal region account for 1% to 2% of all large bowel cancers and 4% of all anorectal carcinomas. The majority of these patients (75% to 80%) have squamous cell carcinomas.1 Approximately 15% have adenocarcinomas.

In 2007, a total of 4650 cases of cancers of the anal region were reported in the United States, including 1900 men and 2750 women.2 It is estimated that there will be 690 deaths per year. Anal cancers, although still uncommon, have increased substantially in incidence during the last 30 years. This increase may be due to sexual transmission of human papilloma virus (HPV), especially HPV-16 and HPV-18.3 It is postulated that, as in cervical carcinoma, with which HPV is strongly associated and may be a necessary factor for development of the disease, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) are the immediate precursors to anal cancer.4,5

Whereas anal squamous intraepithelial lesions are rare in heterosexual men, the incidence is 5% to 30% in HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM). These changes are rare among HIV-negative women, yet common in women with immunosuppression and HPV-related dysplasia of the lower genital tract.6 Anal squamous intraepithelial lesions are linked to HPV and are common in MSM and immunosuppressed patients, especially those who are HIV-positive.7,8 The prevalence of HSIL in HIV-positive MSM reaches 52%.9

There is a clear association between HIV and anal canal cancer. Cross-referencing U.S. databases for AIDS with those for cancer, the relative risk of anal cancer in homosexual men at the time of or after AIDS diagnosis was 84.1.10 The relative risk of anal cancer for up to five years before AIDS diagnosis was 13.9. In a series of 3595 patients undergoing a solid organ transplant the incidence of anal cancer was 0.11%, corresponding to a relative risk of approximately 110.11

Mutations in or aberrant expression of genes in key cellular pathways have been implicated in anal cancer. Overexpression of p53 protein has been studied in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy (combined modality therapy [CMT]). In an analysis involving approximately 20% of patients entered on both arms of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) protocol 87-04 there was a trend towards adverse outcome (decreased local control and survival) in patients overexpressing p53.12 In one study of 55 patients, MIB-1 murine monoclonal antibody measuring KI-67 failed to predict outcome for patients treated with radiation with or without chemotherapy.13 Patel et al. proposed that activation of AKT, possibly through the PI3K-AKT pathway, is a component of the development of squamous cell cancers.14 This latter finding may be of interest now that PI3K-AKT pathway inhibitors are entering early clinical trials.

Anatomy

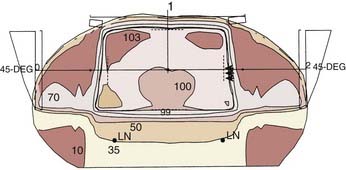

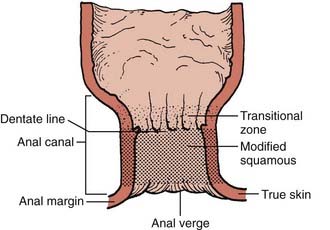

Cancers of the anus can occur in three regions; the perianal skin, the anal canal, and the lower rectum (Fig. 42-1). The anal canal is 3 to 4 cm long and extends from the anal verge to the pelvic floor.15 A clear anatomic distinction between the anal canal and the anal margin is needed, because of the different natural histories of cancers that arise in these two anatomic areas. There is considerable confusion when comparing series in the literature because of the use of different definitions of the anal canal and the anal margin.

FIGURE 42-1 • Anatomy of the anal region.

(From Nigro ND: Neoplasms of the anus and anal canal. In Zuidema GD, ed. Shackelford’s Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1991, WB Saunders, p 319.)

To clarify this issue, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) formed a consensus that the anal canal extends from the anorectal ring (dentate line) to the anal verge.16,17 This is an important distinction, since these two governing bodies agree that anal margin tumors behave in a similar fashion to skin cancers and therefore are to be classified as skin tumors and treated as such. However, if there is any involvement of the anal verge by tumor then it should be treated as an anal canal cancer.

An alternative and clinically oriented classification includes intra-anal, perianal, and skin.18 Intra-anal lesions cannot be visualized or are incompletely visualized when traction is applied to the buttocks. Perianal lesions are visible and are located within 5 cm of the anal opening when traction is applied to the buttocks. Skin lesions are located outside this 5 cm radius and are treated, as stated above, as skin cancers.

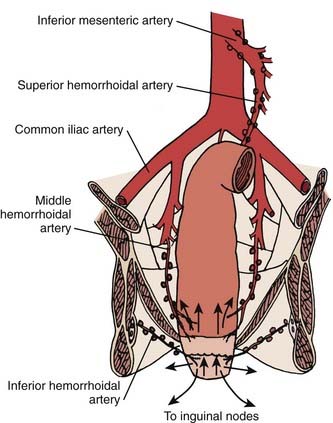

The anal region has an extensive lymphatic system, and there are many connections between the various levels (Fig. 42-2). The three main pathways include (1) superiorly from the rectum along the superior hemorrhoidal vessels to the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes, (2) from the upper anal canal and superior to the dentate line along the inferior and middle hemorrhoid vessels to the hypogastric lymph nodes, and (3) inferior from the anal margin and anal canal to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Pathology

There are a variety of histologic cell types which are present in the anal area (Table 42-1).19 The most common is squamous cell carcinoma. Since the mucosal epithelium over the rectal columns is cuboidal, transitional (cloacogenic) carcinomas can arise. Most investigators agree that prognosis is more dependent on stage than histologic subtype. By contrast, using a multivariate analysis, Das and associates from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center reported a higher distant metastasis rate for patients with basaloid histologies.20 Adenocarcinomas can arise from anal crypts and should be treated as a rectal cancer though with a higher risk of inguinal node spread, given their location and lymphatic flow compared with rectal adenocarcinomas.21 In this chapter, squamous cell and cloacogenic histologies are collectively defined as anal canal cancers. Other rare histologic entities can arise, such as small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas,22 lymphoma, and melanomas.23,24

Table 42-1 Histologic Types of Anal Cancer

| Type of Cancer | % |

|---|---|

| Squamous cell | 63 |

| Transitional (cloacogenic) | 23 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 7 |

| Paget’s disease | 2 |

| Basal cell | 2 |

| Melanoma | 2 |

Modified from Peters PK, Mack TM: Patterns of anal carcinoma by gender and marital status in Los Angeles County, Br J Cancer 48:629, 1983.

Routes of Spread

The primary routes of spread of anal canal cancer are direct extension into soft tissues and lymphatic pathways (see Fig. 42-2). Hematogenous spread is less common. At the time of presentation, pelvic lymph node metastases occur in 30% of patients and inguinal lymph node metastases in 15% to 35%.25 The incidence of metachronous inguinal node metastasis in patients who initially present with clinically negative nodes and are not treated to the inguinal nodes is T1:10%; T2:8%; T3:16%; and T4:11%.26 Most inguinal lymph node metastases are unilateral.

Diagnostic and Staging Studies

Required as well as optional diagnostic and staging studies for anal cancer are shown in Table 42-2. Transanal ultrasound may help identify the depth of tumor penetration, but this has not been validated as a staging tool.27 Abdominal/pelvic computed tomographic (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred imaging study. In a series of 41 patients, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) detected 91% of nonexcised primaries compared with 59% using CT alone.28 In addition, 17% of inguinal nodes negative by CT and physical examination were positive by PET. In a separate trial by Nguyen and colleagues, FDG-PET upstaged 17% of patients with CT-staged N0 disease to N+.29 However, PET, like sentinel node mapping,30 remains investigational. At present, there are no reliable serum tumor markers.

Table 42-2 Workup for Anal Canal Cancer

Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, ed 7, 2010, published by Springer Science and Business Media, LLC, www.springerlink.com.

Staging

In 1997, the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) developed a common staging system. This staging system takes into account the fact that anal canal carcinoma is treated primarily by CMT or, in selected cases, by radiation alone. Abdominoperineal resection (APR) is reserved for patients failing initial treatment. Thus, the TNM classification for anal canal cancers is clinical. The primary tumor is assessed for size and, for T4 tumors, invasion of local structures such as the vagina, urethra, or bladder. The sixth edition of the AJCC staging system is shown in Table 42-3.31 Additional descriptors, although they do not affect the stage grouping, indicate cases needing separate analysis.

Standard Therapeutic Approaches

Treatment of High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions

Though generally accepted as the putative precursor of anal cancer, there is controversy as to the optimal management of HSIL.32 The authors use a targeted approach using high resolution anoscopy to detect dysplastic lesions and electrocautery for destruction. Even patients who are managed in this fashion, if they have a near-circumferential or circumferential anal HSIL5 experience a significantly lower malignant progression rate than those who are only observed (1.2% versus 8% to 13%).33–35 Furthermore, any remaining disease can be safely treated with office-based procedures.

Surgery

Local Excision

Local excision has been used in highly selected patients with tumors that are less than 2 cm in diameter, well-differentiated, or tumors found incidentally at the time of hemorrhoidectomy. Of 188 patients with anal canal carcinoma treated at the Mayo Clinic, a subset of 19 were treated with local excision.22 For the 12 patients with tumors confined to the epithelium and subepithelial connective tissues, 11 had tumors less than 2 cm in size and 1 patient had two lesions. Overall survival for these patients was 100%. One of 12 patients recurred, and this patient was without evidence of disease 5 years after an APR. Patients with tumors penetrating into muscle who refused a colostomy had a higher recurrence rate. These patients often can be salvaged with an APR or CMT.

Ortholan and associates treated 66 patients with T1/TIS (carcinoma in situ) tumors with brachytherapy with or without small field external beam radiation.36 With a median follow-up of 50 months, there were six local failures of which four occurred outside of the radiation field.

Radical Surgery

Radical surgery is reserved for salvage in patients who have failed radiation or in patients who have received previous pelvic radiation therapy. Procedures include APR or more extensive multivisceral resections (i.e., pelvic exenteration). In one series, salvage procedures were associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, 72% and 5%, respectively.37 However, using this radical approach, 83% of patients had negative margins and the 5-year overall survival was 39%.

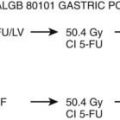

Combined Modality Therapy

Until the late 1970s, the conventional treatment for anal canal cancer was an APR. Nigro et al. challenged this practice with a report of patients with squamous cell cancer of the anal cancer who following preoperative treatment with 30 Gy plus concurrent fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin-C were found to have a pathologic complete response at the time of surgery.38

Since that time, increasing evidence from single-arm phase II studies has indicated that initial CMT yields a complete response rate of approximately 80% to 90% in most patients. Surgery, most commonly an APR, is reserved for salvage. Even in patients with large (≥5 cm) primary cancers, although the complete response rates are lower (50% to 75%), the majority of patients may be spared a colostomy and have an excellent overall survival. The results of these trials will be discussed in “Outcomes.”

Although CMT has been the standard of care since the 1980s, a review of 38,882 patients with anal cancer registered in the National Cancer Data Base from 1985 to 2005 revealed that only 75% received that treatment.39 In addition, those treated with CMT (plus surgery) had higher 5-year survival rates compared to those who did not receive CMT (65% versus 58%, P < .0001)

Techniques of Radiation Therapy

Introduction

A comprehensive discussion of techniques to decrease the toxicity of pelvic radiation such as physical maneuvers, immobilization molds, dietary supplements and radioprotectors, three-dimensional (3D) treatment planning, and other investigational approaches is presented in Chapter 41 (Rectal Cancer) and will not be discussed in this chapter. However, some general principles specific to the design and delivery of radiation for anal cancer will be discussed.

Design of Radiation Therapy Fields for Anal Cancer

The design of pelvic radiation therapy fields for anal cancer is based on knowledge of the natural history of the disease and the primary nodal drainage. Since the internal iliac and presacral nodes are posterior in reference to the external iliac nodes, much of the normal structures in the anterior pelvis can be spared with the use of lateral fields. This approach will underdose the inguinal nodes however they can be supplemented with electrons. General guidelines for the design of pelvic radiation therapy fields for anal cancer are listed in Table 42-4.

Table 42-4 General Guidelines for Radiation Therapy in Anal Cancer

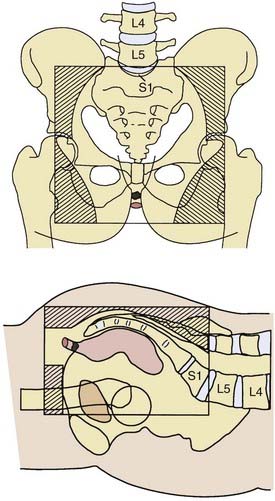

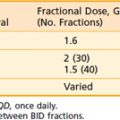

Pelvic Field

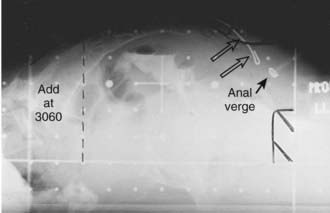

A prone three-field technique (posteroanterior [PA] plus opposed laterals) is recommended. Examples are seen in Figs. 42-3 and 42-4. This arrangement results in the lowest dose to the anterior structures such as the genitalia and bladder. The underdosed inguinal nodes are then treated concurrently with electrons to bring the dose up to 100% of the prescription dose. An alternative method is to use an AP/PA technique. Although this technique treats the pelvic and inguinal nodes in the same field it results in the highest dose to the anterior pelvic structures and skin thereby increasing toxicity. An electron boost for the perineum is not recommended since there will be overlap between the electron and photon fields. The portion of the perineum that needs to be treated should be included in the photon fields. The whole pelvis receives 30.6 Gy followed by a 14.4 Gy cone-down to the true pelvis, for a total dose of 45 Gy. Dosimetry from a representative conventional three-field plan is shown in Fig. 42-5.

It is interesting to note that in the retrospective analysis of 167 patients reported by Das et al, all 5 of the pelvic recurrences occurred at the bottom of the sacroiliac joints (SJ) joints. This is the superior border of the true pelvic field and superior border of the boost field that begins at 30.6 Gy.20

Medial and Lateral Inguinal Lymph Nodes

Following treatment of the pelvis in the prone position the patient is placed in the supine position and the inguinal nodes are treated with electrons. The medial and lateral inguinal nodes are outlined with a 2-cm margin in all directions. The inguinal nodes are included in the PA pelvic photon field. They receive only exit dose from this field; usually approximately 30% to 40% of the pelvic field prescription. This is determined from the treatment plan. Since they need to receive a total of 1.8 Gy/day, the remaining dose should be given concurrently with electrons. The depth of the inguinal nodes can be determined from a CT scan.40,41 If this is not available, a clinical estimate may be used. If the inguinal lymph nodes are biopsy-positive, a three-field technique is still recommended. However, a four-field technique (AP/PA plus opposed laterals) may be needed in order to adequately treat the external iliac nodes. In this setting, inguinal node dose should be 50.4 Gy.

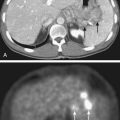

Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is being actively investigated as a method to deliver pelvic radiation therapy with lower acute and long-term toxicity.42,43 Through identification of the dose limiting tissues surrounding the primary tumor and pelvic nodes and by using multiple radiation fields to avoid them, IMRT may allow for dose escalation with less toxicity. Salama and associates treated 53 patients with IMRT-based CMT.44 Patients received 45 Gy to the whole pelvis followed by a boost to a median of 51.5 Gy. Acute grade 3 toxicities were 15% gastrointestinal and 28% skin. Acute grade 4 toxicities included 30% leukopenia and 34% neutropenia. With a median follow-up of 15 months, control rates were local: 84% and distant: 93%. Survival was colostomy free: 84% and overall: 93%. IMRT is being prospectively evaluated by the RTOG (RTOG 0529). An example of an IMRT-based treatment plan is displayed in Fig. 42-6.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree