1. The patient’s self-report of pain is a critical component of a comprehensive pain assessment.

2. Optimal pain treatment may be enhanced by acknowledging cultural differences in the expression of pain.

3. A comprehensive assessment, including the patient’s self-report of pain, will enable the clinician to better evaluate the patient’s experience.

4. Analgesic-based management of pain should begin as soon as possible when indicated. Diagnosis of the pain etiology should not delay administration of analgesics.

5. Providers must consider the special needs of patients with addictive disease to ensure adequate, safe delivery of analgesia.

6. Individuals who appear to present with behaviors suggestive of addictive disease should be given brief interventions and referrals for substance abuse treatment. Chronic repeat visits to non-continuity-of-care providers can be addressed via social service interventions, care plans in conjunction with primary care physicians, and analgesic contracts for emergency pain relief.

7. At the end of a health care visit, the patient should receive instructions with an individualized pain treatment plan, including important medication-specific safety considerations.

Although this patient denied having suicidal ideation , the report of the nurse practitioner should be taken seriously. An entirely reasonable possibility is that the patient was merely venting frustration about the hospital’s policy and her desire for relief. On the other hand, her comments should not be overlooked, as a psychiatric consult or follow-up visit to the patient’s mental health provider may be necessary. The patient’s history also may provide insight into treatment adherence. What are the patient’s obligations? Patients and caregivers obviously have important roles to play in adhering to treatment plans. Patients also have ethical obligations during the course of their treatment, including consideration of the medical team’s advice, compliance, and adherence to a medical contract, if necessary. This contract is commonly employed in situations with concerns about opioid-based therapy and used to formalize an agreement between the physician and the patient. In the present case, should the physician have a concern that the patient may abuse an appropriately prescribed analgesic, an agreement may be used to dispense just enough medication to treat the patient’s immediate needs until she can follow up with her regular provider. Table 8.2 provides an approach to managing pain in cancer patients for whom substance abuse is suspected.

Table 8.2

Pain management in cancer patients suspected of substance abuse

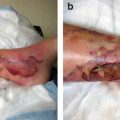

1. Define the mechanism of the pain and treat the primary problem (i.e., infection, tissue ischemia).a |

2. Distinguish the temporal characteristics of the abuse behavior.b |

3. Follow relevant pharmacologic principles of opioid use.c |

4. Nonopioid therapies should be given concomitantly with or even in place of opioids. |

5. Specific drug abuse behaviors should be recognized and dealt with firmly. |

6. Caregivers should set limits to avoid excessive negotiation about drug selections or choices. |

Case Continued: The Patient Returns

Case

Assume the 34-year-old cancer patient described above is prescribed fentanyl and morphine for 2 weeks with instructions to follow up with her primary physician. The patient presents to the EC again 4 days later having used the entire 2-week supply of her pain medications and requesting a refill. What should the emergency physician do? Also, what should be done if imaging of the patient reveals a suspicious lesion, and she is to undergo biopsy in 3 days followed by either surgical replacement of the femur or revision arthroplasty? Would this finding alter the course of action?

Ethical Challenges and Principles

When the patient returns to the EC, physicians find evidence that she has used her medication much more quickly than indicated. Furthermore, she now has even more evidence of substance abuse. Patients may engage in this revolving door of emergency care needs and drug-seeking behavior , which poses challenges to the medical team described above. A common issue is whether the patient can be discharged from care owing to noncompliance. A physician has a professional, not to mention legal, duty to keep from being complicit in illegal activities. At the same time, the patient may be in legitimate distress, pain, and suffering. Because emergency physicians want to engage in informed decision-making, they must consider the importance of the patient’s ability to understand his or her treatment options. This requires the physician to carefully explain not only the decisions being made but also the rationale for those decisions. For example, if a physician decides not to prescribe opioids, providing a sound rationale for not doing so as well as alternatives to treatment of pain will make that decision appear to be beneficial rather than punitive to the patient.

Does the approach change with the added information that the patient has a new lesion? This may make the physician sympathetic to the possibility that the return of her cancer is a legitimate cause of pain . Thus, the physician may be inclined to work with the patient. At the heart of the matter, a physician should take a compassionate approach to pain management that includes strategies for providing the best method of alleviating a patient’s cancer pain.

Pain, Delirium, and Surrogate Decision-Making

Case

A 51-year-old man has been brought to the EC by paramedics. They were called by his 25-year-old daughter, who was visiting from out of town. The patient previously left the hospital after several months of treatment of pancreatic cancer failed to stop or even slow the progression of the disease. When he was told that his disease had metastasized to the liver and doctors gave him no further aggressive treatment options , the patient chose to enter the care of a home hospice service. That was 27 days ago.

The paramedics were called because the patient was waving his hands and speaking of seeing angels and people from his past who had died. He seemed confused about night and day. He also could not remember his children, confusing them with his own brother and sister. He said he had no pain, but he moaned often.

The patient’s wife and 19-year-old son are his primary caregivers, but they were away for the afternoon. His daughter and her husband and child, who live about 200 miles away, were caring for him at the time. The patient’s mother also came to the EC. It was she who called the paramedics and was telling the staff, “My son will not die today and will not die in pain!”

Ethical Challenges and Principles

Delirium is the most common neuropsychiatric syndrome in patients with advanced cancer, particularly elderly patients. It is associated with a high degree of distress in patients, families, and nurses. Delirium is reported at rates ranging from 8 % to 17 % in elderly patients seen in general ECs. Missing a diagnosis of delirium may cause treatment errors, as delirious patients are often given medications to control pain that is not actually present.

The ethical concerns in this case may center on following the patient’s autonomous decisions or accepting a demand to override them by following the wishes of a surrogate decision-maker. The patient’s decision was to recognize and accept that his life is nearing the end and undergo hospice care. He is now presenting with possible pain or delirium, which hospice clinicians have the ability to treat.

The primary concern is treatment of the patient’s symptoms. This means assessment of him for pain and delirium and then treating what is found. This is based on “doing good” and “avoiding harm” for the patient. Some of his family members have a different opinion. In this situation, documentation from an advance directive by the patient as to whom he would like to make decisions for him when he is unable to do so is missing. He has a wife who is not available in person or by telephone at this time. He also has a daughter who is present and a mother who is both present and demanding treatment of his pain and admission of him to the hospital. The physician must determine whether to follow the decisions of the available surrogate decision-makers, wait for his wife to be available, or adhere to the patient’s previous decision to use hospice services.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree