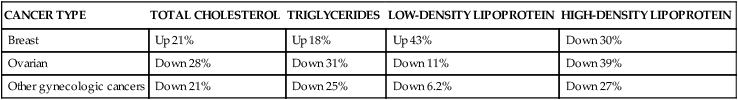

After completing this chapter, you should be able to: • Describe cancer prevention strategies. • Explain how cancer and its treatments affect nutritional status. • Discuss the eating problems associated with cancer and possible solutions. • Explain why nutritional needs must be met during cancer treatment. • Discuss the role of the nurse in counseling for the prevention or management of cancer. Chronic inflammation is now recognized to promote cancer and is one of the common features found with the metabolic syndrome. Inflammation promotes gene mutations leading to cells more prone to cancer development. An inflammatory response is typically accompanied by generation of free radicals (Dobrovolskaia and Kozlov, 2005). Free radicals are known to induce chromosomal changes in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Angiogenesis (the creation of blood vessels) is now known to be linked with cancer development and is influenced by inflammation. Excess body weight, whether overweight or obesity, is linked with the metabolic syndrome and risk of cancer. Hyperinsulinemia is felt to contribute through its promotion of tumor growth. Hyperinsulinemia should be managed with diet and exercise (see Chapters 5 and 8) and/or insulin-sensitizing agents to avoid an increased risk for cancer. Use of insulin by injection should not be undertaken lightly for a person with type 2 diabetes because there may be a resultant increased risk of cancer (Frasca and colleagues, 2008). The list of cancers related to obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and elevated blood glucose levels include the following: • Gynecologic cancers (postmenopausal breast and endometrial cancers) • Cancers connected to the digestive tract (oral cavity, esophagus, gastric, colon, pancreatic, kidney, liver, and gallbladder) • Bladder and prostatic cancers • Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Pisani, 2008; Pischon, Nöthlings, and Boeing, 2008; Renehan, Roberts, and Dive, 2008; Suba and Ujpál, 2006). A number of environmental and dietary factors have been implicated beyond weight concerns. Of major concern are outdoor air pollution by carbon particles, indoor air pollution by environmental tobacco smoke, radon gas released from rock structures below buildings, formaldehyde in housing materials and other chemicals, and nitrates in processed meats (Irigaray and colleagues, 2007). Evidence is building that at least 17 different types of cancer are vitamin D–sensitive. A significant reduction in risk for pancreatic cancer has been found with high levels of serum vitamin D levels as noted with the laboratory value 25(OH)D (see Chapter 3). Poor vitamin D status as generally found in African Americans contributes to their higher incidence and mortality from various cancers, such as pancreatic cancer (Giovannucci, 2009). It is estimated that there is up to a 50% reduction in risk for developing colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer by raising blood levels of 25(OH)D greater than 30 ng/mL by either sun exposure or supplemental vitamin D (Holick, 2008). Total meat and processed meat intake have been directly related to the risk of several cancers related to the digestive tract and to lung, breast, and testicular cancers. Intake of fish and poultry was related to lower risk of several cancers (Hu and colleagues, 2008). Iron, as found in red meat, promotes oxidation that can damage DNA. This damage is similar to that resulting from radiation (Tappel, 2007). The condition of iron overload, or hemachromatosis, has been linked with cirrhosis and increased risk of liver cancer (Horvath and David, 2004). However, no association was found with iron in the development of colorectal cancer in women (Chan and colleagues, 2005). One explanation of differing outcomes related to iron and risk of cancer is fecal occult blood loss with the onset of colorectal cancer (Beale, Penney, and Allison, 2005). The mineral arsenic has been implicated in cancer development. The inorganic form, which is the most toxic and carcinogenic, may be found in drinking water around the world (see Chapter 14). In humans, chronic ingestion of inorganic arsenic (greater than 500 mg/L) has been associated with cancer of the skin, bladder, lung, liver, and prostate. Other micronutrients, many of which are antioxidants, can help reduce the risk associated with arsenic (Anetor, Wanibuchi, and Fukushima, 2007). • Antioxidants (found in dark-green leafy vegetables and deep-orange vegetables and fruits: phytochemicals and a variety of others—see Chapter 3) • Vitamin E (found in nuts and the germ portion of whole grains) • Vitamin C (found in berries, dark-green leafy vegetables, and citrus fruits) The inclusion of foods containing antioxidants helps prevent damage to DNA, thereby promoting genetic stability and reduced cancer risk. Exercise, weight management, and reduced kilocalorie and protein intake has been linked with improved hormonal status and lower risk of cancer (Fontana, Klein, and Holloszy, 2006). The American Institute for Cancer Research (www.aicr.org) notes a reduction in risk of cancer by 30% to 40% through following the Diet and Health Guidelines for Cancer Prevention. These guidelines can serve as appropriate advice for individuals on prevention of cancer. These guidelines are described in the following sections. Increase fiber intake by increased intake of vegetables and fruits. Insoluble fiber (generally the skin and seeds of vegetables and fruits; see Chapter 2) is believed to lower cancer risk in part because the fiber moves food through the gastrointestinal tract faster. This rapid transit of food through the intestines decreases the amount of time carcinogens are in contact with the gastrointestinal mucosa. Other benefits of increasing vegetables and fruits is the impact on serum levels of antioxidants. High plasma levels of ascorbic acid, selenium, and carotenoids have been noted to protect against cancer. High plasma concentrations of carotene are associated both with lower mortality from all causes and with lower rates of cancer in the elderly (Buijsse and colleagues, 2005). A focus on dark-green leafy vegetables will provide vitamins A and C, folate, and magnesium. Retinoids (vitamin A) as found in dark-green leafy and orange vegetables and fruits have cancer preventative and treatment properties. Magnesium is now known to reduce inflammation, which is now being connected with cancer. Legumes and dark-green leafy vegetables are very high in magnesium content. Researchers looking at cancer risk and prevention are increasingly recognizing a multitude of factors that allow complex cellular actions. Therefore the fact that eating a variety of unprocessed foods reduces cancer risk is likely related to the complexity of nutrients found in such foods. Review of various antioxidant supplements, including glutathione (a polypeptide), melatonin, vitamin A, vitamin C, and vitamin E, found no significant evidence in outcomes of cancer treatment (Block and colleagues, 2007). Flavonoids are partially responsible for the cancer prevention effect of common vegetables and fruits (Cherng and colleagues, 2007). The much lower risk of colon, prostate, and breast cancers in Asians may be due to the polyphenol (flavonoid) components and the higher intake of vegetables, fruits, and tea than typical Western diets provide (Kandaswami and colleagues, 2005). Avoid excess alcohol intake. A product of alcohol metabolism, acetaldehyde, causes DNA to become fragile through its destruction of the folate molecule and appears to promote tumor formation. Smoking compounds the risk. Poor diet associated with alcohol abuse can lead to deficiencies of riboflavin, folate, and zinc, which further promote a high risk of throat, colon, liver, and breast cancer (Poschl and colleagues, 2004). For women with risk of breast cancer, avoidance of all alcohol is generally advocated. Some newer research suggests a diet containing adequate folate may allow such women to safely include moderate amounts of alcohol (see section on breast cancer) as advised by the American Heart Association to lower risk of cardiovascular disease. Limit saturated fat intake because it is related to increased incidence of cancer. Most polyunsaturated fats also are now felt to increase cancer risk because of their tendency to oxidize and form free radicals. The exception is the form of polyunsaturated fat known as omega-3 fatty acids, especially the long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), present in fatty fish and fish oils, which appear to be protective against various forms of cancer (see section on types of cancers below). Several mechanisms whereby omega-3 fatty acids reduce cancer risk have been proposed. These include reduced production of the fatty acid arachidonic acid (see Chapter 2), altered gene expression, alteration of estrogen metabolism, changes in production of free radicals and reactive oxygen species, and mechanisms involving insulin sensitivity and membrane fluidity (Larsson and colleagues, 2004). Reduction in inflammation levels from the inclusion of fatty fish with EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids also may explain the association with reduced cancer risk (Babcock, Dekoj, and Espat, 2005). Monounsaturated fats, as found in olive oil, appear to have at least a neutral effect on cancer risk. The traditional diet of Greece, still followed in Crete, suggests a lower risk of cancer. There is a high intake of olive oil, fiber from a variety of plant-based foods, and fish providing omega-3 fats (Simopoulos, 2004). One way to decrease the intake of saturated and polyunsaturated fats is to limit the total fat intake. However, because the monounsaturated fats found in olive oil and the omega-3 fatty acids found in cold-water fish appear at least neutral if not protective against cancer, the Mediterranean-style diet (similar to the TLC diet; see Chapter 7) is an alternative to low-fat diets in the battle against cancer and other chronic illnesses such as heart disease and diabetes. Minimize salt intake to lower cancer risk, especially gastric cancer (Tsugane, 2005). Chinese-style salted fish increases the risk for nasopharyngeal cancer, particularly if eaten during childhood, and should be eaten only in moderation (Key and colleagues, 2004). The impact of salt on risk of cancer may have to do with its ability to erode the protective mucous lining of the stomach. A similar irritant effect on the pharyngeal region may also occur. The fourth leading type of cancer in men in the United States is bladder cancer, which ranks ninth in worldwide cancer incidence. Men have a greater incidence of bladder cancer than women. Cigarette smoking and chronic urinary tract infections (UTIs) are associated with an increased risk of this cancer (Murta-Nascimento and colleagues, 2007). Cranberry juice has been shown to reduce risk of UTIs. Other potential risk factors include drinking tap water with chlorination by-products or arsenic. Heavy consumption of phenacetin-containing analgesics has been shown to cause bladder cancer in humans (Jankovi Factors that reduce risk of bladder cancer include intake of fruits and vegetables. Intake of B vitamins (B2, B6, B12, and folate—see Chapter 3 for food sources) and retinol as found in deep orange and dark-green leafy vegetables are associated with a reduced risk. In particular vitamin B6 and retinol showed the strongest evidence of risk reduction (García-Closas and colleagues, 2007). Compounds in cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, and cabbage) have an anticarcinogenic effect on bladder cancer (Zhao and colleagues, 2007). Two mushroom extracts, when combined with moderate amounts of vitamin C, became highly cytotoxic, resulting in greater than 90% cell death related to bladder cancer (Konno, 2007). Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death among U.S. women. Breast cancer can also occur in men, although rarely, and generally there is a worse prognosis because of a delay in diagnosis. Excess weight appears to contribute to risk. Postmenopausal overweight women have an increased risk, as do premenopausal women who have a high waist-to-hip ratio (greater than 0.87) (Tehard and Clavel-Chapelon, 2006). Because estrogen levels increase as a result of obesity, this is one factor behind the increased risk of breast cancer found with obesity (Suzuki and colleagues, 2006). Evidence supports a moderate association between type 2 diabetes and the risk of breast cancer, particularly among postmenopausal women (Xue and Michels, 2007). A low level of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, as found with the metabolic syndrome, has recently been related to increased breast cancer risk in overweight and obese women (Furberg and colleagues, 2005). The common link with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and breast cancer appears to be insulin resistance with high insulin levels. Hyperinsulinemia has been associated with poor outcomes in breast cancer. Medical nutrition therapy that helps normalize hyperinsulinemia is important in early-stage breast cancer and for the long-term management of breast cancer survivors (Goodwin and colleagues, 2009). See Chapters 5 and 8 on managing hyperinsulinemia via low–glycemic load meals. Traditional dietary goals have been aimed at low-fat diets to prevent breast cancer. However, in one study among postmenopausal women, a low-fat diet did not reduce breast cancer risk (Prentice and colleagues, 2006). This finding was supported by another study over a 7-year period that found a low-fat diet high in fiber did not reduce reoccurrence of breast cancer (Pierce and colleagues, 2007). On the other hand, a large prospective study found dietary fat intake was directly associated with the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer regardless of type (Thiébaut and colleagues, 2007). The different outcomes of research related to dietary fat intake likely are due to the type of fat. A low incidence of breast cancer has been noted in the Mediterranean region, where there is a high intake of olive oil. It has been suggested that the beneficial effect of olive oil on lowering risk of breast cancer is due to the many phenolic compounds found in olive oil (Menendez and colleagues, 2007). Intake of oily fish suppresses at least one form of breast cancer. The research suggested there was suppressed tumor incidence and reduced mammary gland abnormality (Sun, Berquin, and Edwards, 2005; Yee and colleagues, 2005). This positive impact of fish oil may result, in part, from decreased inflammation as associated with cancer. See Chapters 5 and 7 on reducing inflammation with diet. For women with the metabolic syndrome, lowering carbohydrate intake can be presumed beneficial. In fact, a high glycemic index has been associated with increased breast cancer risk, especially among those who were physically inactive or those of normal weight who had used hormone replacement therapy (Silvera and colleagues, 2005). In premenopausal women, increased risk with high glycemic load was related only to overweight and obese women, not women of normal weight (McCann and colleagues, 2007). This is likely due to women of normal weight being insulin sensitive, not insulin resistant. Among women of Italian heritage a high–glycemic load diet increases risk of breast cancer particularly in premenopausal women and those of normal weight (Sieri and colleagues, 2007). Following the Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC) diet (see Chapter 7) as advised for management of the metabolic syndrome should help reduce risk of breast cancer for women with insulin resistance. Increasing physical activity levels also is linked with lower risk of breast cancer (Bardia and colleagues, 2006). Physical activity improves insulin sensitivity. A high intake of fruits and vegetables has been shown to significantly decrease risk of breast cancer (Fung and colleagues, 2005). It may be the dietary fiber from fruit and cereal that helps reduce breast cancer risk (Suzuki and colleagues, 2008). A high folate intake, as found in high amounts in legumes and greens, from diet or supplements is associated with a lower incidence of postmenopausal breast cancer (Ericson and colleagues, 2007). Alcohol consumption, even in moderation, is associated with breast cancer risk, and the risk was found to be greatest in women with lower total folate intake (Stolzenberg-Solomon and colleagues, 2006). The usual recommendation is for women at risk of breast cancer to avoid all alcohol. However, among women with folate intake higher than 350 mcg no association between the alcohol intake and the breast cancer incidence rate was found (Tjonneland and colleagues, 2006). Thus women who want to and can keep alcohol intake within moderate amounts should increase folate intake, especially if known to have a high risk for breast cancer. Folate is found in dark-green leafy vegetables, legumes, whole grains, milk, and fish. A traditional Asian type of diet of vegetable and soybean products is found with lower breast cancer among Chinese women, whereas a Western type of diet increases breast cancer risk among those who are menopausal (Cui and colleagues, 2007). Phytoestrogens, as found in soy, are a group of plant-derived substances that are similar to estradiol. Because a decreased risk of breast cancer has been recognized in women from Asian countries, phytoestrogens have been implicated as the beneficial factor. Early exposure to soy products in childhood or early adolescence is suggested to be protective. This same benefit has not been shown among breast cancer survivors. The phytoestrogen genistein as may be found in supplemental form interferes with the effects of tamoxifen to reduce breast cancer cell growth (Duffy, Perez, and Partridge, 2007). Soy supplements containing the active ingredients found in soy are generally discouraged. Green tea polyphenols have been linked with reduced cancer risk, including breast cancer (Thangapazham and colleagues, 2007). High waist circumference is an independent risk factor for colorectal adenoma (Kim and colleagues, 2007). Hyperinsulinemia found with excess weight and kcalorie intake with low physical activity also has been associated with colorectal cancer. Other factors include excess alcohol intake, smoking, and low consumption of folate and the amino acid methionine—see Chapter 2 (Campos and colleagues, 2005). Women with low levels of insulin-like growth hormone and C-peptide (see Chapter 5) were found to have low risk of colon cancer, whereas elevation of either was associated with increased risk (Wei and colleagues, 2005). In persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus, epidemiologic studies show an increased risk for colorectal cancer and an even higher risk if patients are treated with sulfonylureas (see Chapter 8) or insulin. Individuals with type 2 diabetes who are on chronic insulin therapy were found to have three times the risk of colon cancer compared with those without insulin therapy (Chung and colleagues, 2008). It is advised that all patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus undergo colonoscopy before starting insulin therapy and have regular screening at least every 5 years (Berster and Göke, 2008). Diet and alcohol have an impact. Alcohol is associated with colon cancer. Men who consume greater than or equal to 5 oz of alcohol weekly have twice the risk of colorectal cancer of those who drink less alcohol. Low intake of vitamin B6 (see Chapter 3) is related to colon cancer, especially when combined with higher alcohol intake (Ishihara and colleagues, 2007). A number of dietary factors are linked with lower risk of colon cancer. Salt and other substances as found in smoked or salted fish increase risk (Marques-Vidal, Ravasco, and Ermelinda Camilo, 2006). Sweets, refined white flour products, and red meat products are linked with increased risk, whereas a variety of high-fiber foods, low-fat dairy products, white meat, and fish are recommended to lower risk (Ströhle, Maike, and Hahn, 2007). This type of dietary pattern helps increase intake of folate and vitamin B6 (see Chapter 3), which are associated with reduced colorectal cancer risk. The use of multivitamin supplements is not related to colorectal cancer risk (Zhang and colleagues, 2006). Vitamin B6 may further play a role in the prevention of colorectal cancer among those who drink alcohol, especially women (Larsson and colleagues, 2005). A dose of 1000 International Units of vitamin D per day is associated with a 50% reduction in colorectal cancer incidence (Grant, Garland, and Gorham, 2007). The association of the metabolic syndrome with colon cancer suggests dietary advice should be aimed at reducing carbohydrate intake, rather than focusing on total fat intake. It was found a low-fat dietary pattern did not reduce the risk of colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women during an 8-year period (Beresford and colleagues, 2006). Increasing omega-3 fatty acids is related to reduced risk (Theodoratou and colleagues, 2007). High–glycemic load meals, fructose, and sucrose have been linked with increased colorectal cancer risk among men (Michaud and colleagues, 2005). Research on fiber intake is less conclusive, but it may be related to other aspects of diet and lifestyle (Michels and colleagues, 2005). A Mediterranean diet, which has a low glycemic index and with traditional small quantities of food, a low glycemic load as well, is associated with reduced risk. This type of diet is similar to public health initiatives such as the 2005 U.S. Dietary Guidelines, MyPyramid Food Guidance System, and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet—see Chapters 1 and 7 (Dixon and colleagues, 2007). There is conflicting evidence regarding intake of calcium and vitamin D from dairy intake or supplements. Some research links intake with lower rates of colon cancer (Larsson and colleagues, 2006a; Park and colleagues, 2007). Other research, such as the large, prospective, female cohort from the U.S. Women’s Health Study found no association with reduced risk (Lin and colleagues, 2005). The endometrial lining of the uterus is a common site of cancer in women. Conditions found with the metabolic syndrome are linked with both endometrial and ovarian cancers. This includes the link between inflammation and gynecologic cancers (Goswami and colleagues, 2008). Obesity and hyperinsulinemia are linked. High estrogen levels, as found with obesity, appear to be a major risk factor for endometrial cancer (Gunter and colleagues, 2008). Women with polycystic ovary syndrome, found with the metabolic syndrome and obesity, have increased risk of endometrial cancer (Costello, 2005). Altered lipid levels also are linked. Ovarian cancer is associated with significantly lowered HDL and total cholesterol levels (see Table 10-1). Table 10-1 Relationship of Plasma Lipid Levels With Gynecologic Cancer Data from Qadir MI, Malik SA: Plasma lipid profile in gynecologic cancers, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 29(2):158-161, 2008. Folate plays an important role in cancer prevention. Dietary folate intake was linked with reduced endometrial cancer risk among Chinese women (Xu and colleagues, 2007). Leafy greens, rich in folate, also are high in retinoids and carotenoids that are related to low risk of ovarian cancer. It further appears that carotenoids have a role in treatment of ovarian cancer (Czeczuga-Semeniuk and Wolczynski, 2005). Research on the role of carbohydrates with diet and cancer is limited. There is some evidence that plasma insulin levels from a high–glycemic load diet may influence ovarian cancer risk (Silvera and colleagues, 2007a). Limited evidence has indicated high intakes of lactose might increase the risk for ovarian cancer (Key and Spencer, 2007). However, a meta-analysis did not find any association between milk and dairy products and ovarian cancer except for a nonsignificant increased risk from whole milk and butter (Qin and colleagues, 2005). A 20% low-fat, high-fiber approach has not been shown to be effective at reducing endometrial or ovarian cancer in the short-term, but over an 8-year-period there was a lower rate for ovarian cancer (Prentice and colleagues, 2007). Ovarian cancer risk was minimally linked among women who drank more than four cups coffee daily compared with women who did not drink coffee. No association was found among tea drinkers (Silvera and colleagues, 2007b). A relatively new compound, called acrylamide, was found in starchy foods prepared at high temperatures, such as with fried foods. This substance has been associated with increased risk of postmenopausal endometrial and ovarian cancer (Hogervorst and colleagues, 2007). The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is on the rise in the United States. Its precursor condition, Barrett’s esophagus (a premalignant lesion related to ulceration of the lower esophageal section that can lead to strictures inhibiting the movement of food into the stomach), also is on the rise. Zinc deficiency may contribute to Barrett’s esophagus (Guy and colleagues, 2007). Studies suggest a reduced risk of esophageal cancer in populations with a high intake of fish. One study found supplementation with the omega-3 fatty acid EPA significantly reduced inflammation related to Barrett’s esophagus (Mehta and colleagues, 2008). There is a strong correlation with an increased intake of carbohydrate, especially related to intake of corn syrup as found in sweetened beverages. This may be due to the rise in obesity rates as linked with higher intake of kcalories from sugar-based beverages (Thompson and colleagues, 2008). Esophageal cancer is related to smoking and use of alcohol. There is an increased risk with the combination of excess alcohol intake and smoking (La Vecchia, Zhang, and Altieri, 2008). Eating food rapidly and frequent intake of pickled vegetables also have been implicated in increased risk of esophageal cancer (Yang and colleagues, 2005). How increased pace of eating is associated with esophageal cancer is unknown. The reduced saliva release with reduced chewing may play a role. Saliva helps to neutralize acidity of the oral cavity, which may play a role in esophageal cancer. Increased consumption of fruits (including oranges/tangerines), seafood, and milk were found to be protective against the development of esophageal cancer (Fan and colleagues, 2008). This may be due to the intake of vitamin C, with research of supplements showing a beneficial impact. It was found that those who took a multivitamin, 250 mg of vitamin C, or 180 mg of vitamin E had lower risk of esophageal cancer (Dong and colleagues, 2008). Gastrointestinal cancers account for 20% of all cancer incidences worldwide. A variety of factors appears to increase risk of gastric cancer. The risk factors most strongly associated with gastric cancer are diet and the gastric bacterial infection caused by Helicobacter pylori. Lower risk was found with increasing intake of several micronutrients and vegetables, especially cruciferous vegetables (Epplein and colleagues, 2008). A positive family history of gastric cancer is a risk factor. Low serum pepsinogen levels reflect gastric atrophy, and screening may help to identify populations at high risk for gastric cancer. H. pylori screening and treatment is recommended for those with high risk of gastric cancer (Fock and colleagues, 2008). Glycemic load and hyperinsulinemia have been connected with gastric cancer risk. Observational studies support a protective effect of citrus fruit intake in the risk of stomach cancer (Bae, Lee, and Guyatt, 2008). Gastric cancer is a major health burden in the Asia-Pacific region, and a high intake of salt appears to be the cause. Data also suggest that high intake of nitrosamines, processed meat products, and overweight and obesity are associated with increased risk for gastric cancer around the world (Liu and Russell, 2008). Risk of leukemia has been linked with oxidative stress. This may be precipitated by environmental factors, but poor nutritional intake adds to the risk. A low level of the antioxidant minerals selenium and zinc have been noted, along with a high copper status, in leukemia patients. It is not known if this is the cause or the consequence of leukemia (Zuo and colleagues, 2006). Children with Down syndrome have shown decreased levels of zinc and a fiftyfold increased risk of developing acute leukemia during their first few years of life. Use of a multivitamin supplement was not found to reduce risk of leukemia (Blair and colleagues, 2008).

Cancer

Nutrition Prevention and Treatment

WHAT ARE THE CAUSES OF CANCER AND HOW CAN ONE REDUCE CANCER RISK?

EAT PLENTY OF VEGETABLES AND FRUITS

DRINK ALCOHOL IN MODERATION, IF AT ALL

SELECT FOODS LOW IN FAT AND SALT

HOW DOES NUTRITION INCREASE OR REDUCE RISK OF SPECIFIC CANCERS?

BLADDER CANCER

and Radosavljevi

and Radosavljevi , 2007). Obesity contributes modest adverse risk for bladder cancer (Koebnick and colleagues, 2008).

, 2007). Obesity contributes modest adverse risk for bladder cancer (Koebnick and colleagues, 2008).

BREAST CANCER

COLORECTAL CANCER

ENDOMETRIAL AND OVARIAN CANCER

CANCER TYPE

TOTAL CHOLESTEROL

TRIGLYCERIDES

LOW-DENSITY LIPOPROTEIN

HIGH-DENSITY LIPOPROTEIN

Breast

Up 21%

Up 18%

Up 43%

Down 30%

Ovarian

Down 28%

Down 31%

Down 11%

Down 39%

Other gynecologic cancers

Down 21%

Down 25%

Down 6.2%

Down 27%

ESOPHAGEAL CANCER

GASTROINTESTINAL CANCER

LEUKEMIA

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Cancer

cup of sugar. Even though this is fructose, not sucrose, excess may promote hyperinsulinemia and cancer risk. Vegetable juices are lower in sugar content and likely will reduce cancer risk, such as with tomato juice and its lycopene content.

cup of sugar. Even though this is fructose, not sucrose, excess may promote hyperinsulinemia and cancer risk. Vegetable juices are lower in sugar content and likely will reduce cancer risk, such as with tomato juice and its lycopene content.