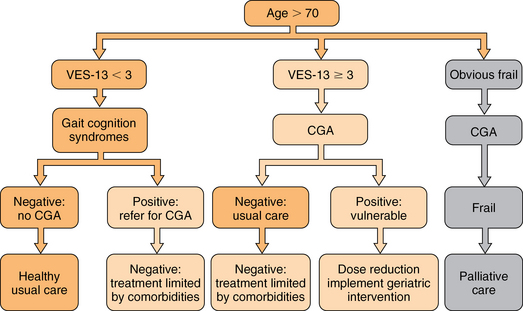

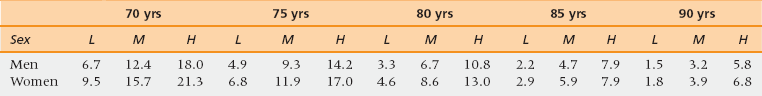

46 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Be aware of age-related differences in cancer biology that affect age-related decisions for the management of specific cancers. • Summarize general principles of cancer management applied to the elderly. • Be prepared to apply geriatric principles to maintaining functional status of elderly cancer patients. • Be familiar with disease-specific treatment guidelines for several common cancers in the elderly. • Apply current cancer prevention and cancer screening guidelines appropriately to the elderly. • Understand special issues in the care of cancer survivors. Cancer is the second leading cause of death and a major cause of morbidity for persons age 65 and older. More than 50% of all new solid tumor diagnoses are made among people over age 65.1,2 In addition there are now more than 11 million cancer survivors in the United States, 6.5 million of whom are of Medicare age.3 Cancer control in older individuals includes early diagnosis, prevention, individualized treatment plans, supportive care, end-of-life care, and survivor care. The primary care physician (PCP) plays a key role in each stage of cancer care and it is increasingly clear that patients benefit from having a multidisciplinary team. More than half of new diagnoses of the common solid tumors including lung, breast, colon, prostate, and ovarian cancers occur in those aged 65 and older. For most of these cancers, incidence increases with age at least to age 85, after which the rate of increase levels off. However, the biological behavior of most common solid tumors changes with the age of the patient as a result of mechanisms shown in Table 46-1.4 TABLE 46-1 Selected Age-Related Changes in Tumor Biology5–7 Data from Dendaluri N, Ershler WB. Aging biology and cancer. Semin Oncol 2004;31:3580-7; Irminger-Finger I. Science of cancer and aging. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1844-51; and Hornsby PJ. Senescence as an anticancer mechanism. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1844-51. Poorer survival of elderly cancer patients is partly because of differences in the cancer biology and possibly because of the choices made about their treatment. Examples of neoplasms of older people that are less responsive to chemotherapy include osteosarcomas, glioblastomas, and several hematologic and lymphatic malignancies. Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas have different genetics and different prognostic characteristics in the elderly. Age itself should not determine the treatment of cancer. Sixty-seven percent of older persons with AML have a poor prognosis biology that is multidrug resistant, but 33% have a disease responsive to current chemotherapy. Although 80% of older women have an indolent form of breast cancer that is hormone sensitive, 20% of older women breast cancer patients have an aggressive disease that may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy.11 Recent advances in genetic analysis of tumor cells promise to improve chemotherapy targeting. That is, for some malignancies, oncologists can predict which cancers will respond to available chemotherapy agents and which will not. In the elderly this is especially useful because the decision to accept highly toxic treatment should be conditioned by the probability of response. Examples of cancer cell markers effectively selected by newer targeted chemotherapy agents include HER2/neu, which indicates responsiveness to trastuzumab; KRAS in colon cancer predicts sensitivity to cetuximab. Other genetic markers are BRAF and mTOR. Molecular profiling of tumors is rapidly emerging as an exciting modality and testing has greatly grown in availability.12 In addition to tumor biology, aspects of host resistance may account for poorer survival in the elderly. This includes both systemic responses and age-related differences in the tumor microenvironment. Immune senescence impairs surveillance for abnormal cells.9 Microenvironmental factors such as angiogenesis and tissue growth factors differ with age as do whole organism characteristics such as renal function and cardiovascular fitness. One well-studied example is the inflammatory response. For example, the concentration of interleukin (IL) 6 in the circulation increases with age. Some cancers also stimulate the inflammatory response. Chronic inflammation may play a role in tumor formation, for example in some gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies such as colon cancer. Blunted T-cell and natural killer (NK) cell immune surveillance has been thought to undermine host response to neoplastic cells.9,10 Clinical applications of these observations include the following: Contrary to expectations, some cancers such as myeloid and lymphoid malignancies may become more aggressive with age. Some, such as non–small cell lung adenocarcinoma, estrogen/progesterone responsive positive breast cancers, and prostate adenocarcinomas, are more indolent because the microenvironment does not stimulate growth. Applying clinical trials findings to practice always involves comparing the trials population with the local clinical population. In cancer treatment the clinical trials conducted by the cooperative groups rarely include patients older than age 70. One factor for the low inclusion rate is that older adults are rarely asked to participate even though they are just as willing, all things being equal, as younger patients.13 If clinical trials require considerable travel elderly patients may be reluctant to drive or may lack a household driver. The subgroup analyses of clinical trials of adjuvant chemotherapy for breast and colon cancers have shown equal benefit from equal treatment in terms of standard oncology endpoints of tumor response and disease free survival. However, population-based data demonstrate that elderly patients do more poorly than younger patients and receive less treatment even when adjusted for stage of disease and inferred performance status.14 The reasons for differences between the clinical trial results and community results include referral bias of the most fit patients to the trial centers, better adherence to standards of cancer-directed care including choice of agents, dose-density and toxicity monitoring at referral centers, and better quality of supportive and follow-up care through the trial centers. At least two oncology professional societies have studied these data and offered recommendations for the treatment of specific cancers in elderly patients. The International Society for Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) maintain updated treatment recommendations and online links to current literature for the elderly on their websites. The cooperative trials groups have shown heightened awareness of the need for age-representative trials design and enrollment, and more patient-centered rather than disease-centered outcomes.15 The overall goal is to avoid undertreating curable and controllable disease in consenting patients, and to avoid overtreating both indolent and poor prognosis disease. Finding the “just right” approach requires experience, collaboration, and expertise. Principles for cancer treatment in older adults have been endorsed by SIOG and NCCN (Box 46-1). Oncologists typically assess patients as fit or unfit for standard therapy (Figure 46-1). If they feel a patient will not tolerate standard therapy they may attempt dose-reduced therapy or treatment with a single agent as opposed to combination therapy. This approach is flawed because it is not evidence-based, and because for reasons previously explained, the evidence base is limited with regard to older patients. International data reveal that elderly patients receive less cancer-directed therapy, so the lessened toxicity is also accompanied by less efficacy.16 Figure 46-1 A decision tree for staging the aging. CGA, comprehensive geriatric assessment ; VES, Vulnerable Elders Survey. (Data from Rodin MB, Mohile SG. A practical approach to geriatric assessment in oncology. J Clin Oncology [Review] 2007;25(14):1936-44; and Mohile SG, Bylow K, Dale W, et al. A pilot study of the Vulnerable Elders’ Survey-13 as compared to comprehensive geriatric assessment for identifying disability in older prostate cancer patients receiving androgen ablation. Cancer 2007;109:802-10.) Global functional/fitness-for-treatment assessments do not make explicit the clinician’s subjective biases. The most commonly used functional assessments in the United States are the Eastern Cooperative Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) and the Karnovsky Performance Status (KPS) scales. Both are subjective but nonetheless have withstood the test of time and continue to be highly predictive of early mortality.17 These scales are used to track treatment tolerance not to predict it. They do not identify specific risk factors for treatment intolerance that may be remediable. There are differences in practice style. Some oncologists choose to front load the treatment to give as much chemotherapy as possible before the patient needs a break. Some choose to test tolerance by lowering doses and spreading them out to lessen toxicity, but that also lessens tumor cell killing. Neither approach has clinical trial–based evidence. For example, in breast cancer, single agents, either alone or as a sequential regimen in metastatic disease, are better tolerated than combination therapies. The combination therapies produce better results in terms of tumor shrinkage but survival does not seem to differ between the approaches. The current weight of opinion among oncologists specializing in treating older adults is to try to give standard protocols for which there is evidence if the patient is fit and willing.18 Over the past several years there have been increasing numbers of studies in which geriatric screening tools are used to describe clinical samples of elderly cancer patients. As yet there are limited data showing that geriatric screening tests incorporated into cancer treatment affect decisions or outcomes.19 However, there are a few preliminary studies, mainly from France, that may soon yield results.20 A source of resistance to routine geriatric assessment has been that oncologists are concerned that performing many screening tests will be too time consuming for their practices and that the screening tests will generate information that they cannot use.21 Several studies have tested short screens to identify only those patients who should be comprehensively evaluated and to quantify the amount of time it takes to gather the data.22–24 The various components of a comprehensive geriatrics assessment include functional status (ADLs and IADLs), cognitive screening, review of medications for potentially harmful or just unnecessary polypharmacy, nutritional status, vision and hearing, gait and fall risk assessment tools, depression, and delirium. There is no reason to choose one specific validated screening tool over another with which the clinician is familiar or has comparative data in the medical record for the patient. It is important to recognize that these tools were devised to determine intermediate- to long-term outcomes including loss of independence (nursing home placement) and longevity over a range of several years.25 Remaining life expectancy (RLE) is a prognostic indicator, obviously not an absolute prediction of the future. For an older person with a long RLE, a new cancer diagnosis may shorten RLE. The value of having an estimate is to draw a frame around the expected course of the disease within a realistic span of time (Table 46-2).26 A highly treatable cancer may have a low probability of recurrence within the patient’s RLE, even if it is not completely “cured.” The mirror image of this assessment is whether the treatment poses a higher risk than the cancer or whether the cancer is likely to progress during the patient’s RLE or not. Heuristically, is the patient’s precancer life expectancy less than 5, 5 to 9, or 10 or more years? With successful treatment, what is the probability of symptomatic progression within 5 years? Is it less than 10%, less than 50%, less than 80%? Do the risks of standard treatment—including surgical risk, serious toxicity, or suffering or death—outweigh any theoretical benefit? Several studies have specifically examined the performance of common functional scales for chemotherapy tolerance.27–30 TABLE 46-2 Remaining Life Expectancy (RLE) in Years by Age (5 yrs), Sex, and Quartile (Lowest, Middle 2, Highest) LE, Life expectancy; L, low quartile of LE; M, middle quartile of LE; H, high quartile of LE. Adapted from Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: A framework for individualized decision-making. JAMA 2001;285:2750-6. Low-risk asymptomatic cancers can be watched in frail patients; cancers that are likely to become symptomatic during a short time and that are responsive to low-toxicity therapy can be treated in frail patients. Treatment for high-risk tumors requiring highly toxic therapy should be offered only to the most fit patients where RLE will allow them to enjoy their survival. Extreme frailty is usually recognized without difficulty. Because oncologists generally see a selected group of reasonably healthy older patients, geriatricians’ greatest contribution is in decision making for the apparently fit but “vulnerable” or “subclinical frail” patients.23 The National Cancer Center Network recognizes that some form of geriatric assessment provides information essential to the treatment of persons 70 years old or older.31 These guidelines also recognize the importance of caregiver support, out-of-pocket costs for people on fixed income, access to care, depression, malnutrition, and polypharmacy. Patients who are dependent in IADLs, especially in the use of transportation, ability to take medications, and money management, are at increased risk for complications. It is important to lay out in a clear and systematic manner the likely course of the cancer if not treated or with best possible treatment and best expected outcome based on the cancer alone. Then the individual’s life expectancy based on stable comorbidities and functional status needs to be measured against the likely duration of toxic therapy and duration of remission to be gained. Then it makes sense to let the patient weigh the balance and set his or her goals.32,33 Recently, two important studies have shown a role for geriatric consultation. One trial involved randomizing advanced lung cancer patients to usual care or to proactive palliative care assessments. The palliative care group lived longer and terminated active treatment earlier.34 In an observational study in the context of a clinical trial, advanced lung cancer patients who had previously documented IADL dependencies were 50% more likely, patients who could not walk a block outside their homes were 75% more likely, and patients who had a previous fall were 2.5 times more likely to experience serious chemotherapy toxicity.27 Geriatricians have been careful to separate the patient’s functional status from comorbidity burden. This separation appears to hold with cancer patients, because studies confirm that toxicities are independently predicted by functional variables and by summary comorbidity variables. Simply doing assessments will not change outcomes. However, the geriatric model of multidisciplinary continuity of care may improve outcomes as demonstrated in a multicenter Veterans Administration trial showing that among functionally impaired veterans randomized to geriatric outpatient care, those with cancer benefitted the most with respect to quality of life.35 Adverse events beyond direct drug toxicity should be considered in future studies when additional outcomes can be built into the trial protocols. Chemotherapy is largely an outpatient procedure and oncology nurses are skilled in administering preventive protocols to reduce immediate nausea and vomiting, cutaneous itching and burning, and anxiety. However, elderly patients who experience less immediate chemotherapy induced nausea (CIN) are more subject to delayed toxicities including nausea, bone marrow suppression, neutropenia, anorexia, fatigue, and diarrhea.36 The impact of known late toxicities may be more serious in the elderly because of preexisting vulnerabilities. At some institutions out-of-town patients may be kept close by in dedicated housing near the hospital or admitted to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) to carry them through chemotherapy. Thus nursing homes need to be aware and prepared to manage predictable delayed toxicities.37 SNF-level care anticipates functional problems. An elderly patient at home, especially alone at home, who is suffering from fatigue, anorexia, or low-grade delirium may not be able to recognize, report, and self-manage toxicities. Recognizing mild mobility problems, mild cognitive impairment, or dementia is crucial for an elderly patient’s ability to maintain nutrition and hydration, and avoid falls. Minor mobility problems may get worse as a result of orthostatic hypotension, fatigue, anorexia, and sleep dysfunction. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, and mucositis require adequate supports in the home to manage medications, fluids, and toileting. Active supportive symptomatic management is crucial. Elective surgery for cancer is reasonably safe throughout the ninth decade of age.38,39 The major differences in surgical mortality between younger and older individuals are seen in emergency surgery of the GI tract. Standard screening for cancer of the large bowel may substantially reduce the need for emergency surgery. Elective cancer surgery poses no greater risk than noncancer surgery. The usual perioperative risk stratification and monitoring for delirium and early nutritional support should be performed. Early mobilization and referral for rehabilitation should also be encouraged. By contrast, surgical debulking of ovarian cancers is trending toward longer procedures to achieve more complete excisions. Improved radiation technology, such as cyberknife, may in some cases eliminate the need for surgical excision of isolated small tumors.40 Several studies attest to the safety of radiation therapy in older patients, even those aged 80 or older.41 Radiation therapy can sometimes be used in lieu of surgery for curative purposes in selected patients and for palliation of pain and obstruction. The combination of chemotherapy and radiation for cancer of the larynx, esophagus, and small rectal tumors produces results comparable to surgery with the advantage of organ preservation.42 Radiation and surgery remain effective strategies for curative prostate cancer therapy, but the best use of these interventions is actively under discussion.43 Systemic therapy involves oral and intravenous agents of several classes (Box 46-2). The aromatase inhibitors (AIs) have proven more effective than the older selective estrogen receptor modulators (tamoxifen and toremifene) in the management of breast cancer. For the majority of practitioners, these compounds are now the initial treatment of choice, both in the adjuvant setting and in metastatic disease.44

Cancer

Cancer in the elderly

Cancer biology and aging

Disease

Prognosis

Mechanism

Acute myelogenous leukemia

Worse

Increased multiple drug resistance. Increased incidence of stem cell leukemia8

Large cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Worse

Increased circulating IL-6 stimulates lymphoid proliferation9,10

Breast cancer

Better

Increased expression of hormone receptors, well differentiated, slowly proliferating; reduced production of tumor growth factors by host

Non–small cell lung cancer

Better

Less chemotherapy responsive but more indolent for unknown reasons

Celomic ovarian cancer

Worse

Unknown

Evidence-based treatment

Staging the aging

General principles of cancer management

Local therapy

Systemic therapy

Hormonal therapy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Cancer