Buttockectomy

James C. Wittig

Martin M. Malawer

BACKGROUND

The gluteus maximus (buttock) is a common site for highand low-grade soft tissue sarcomas. The gluteus maximus is a “quiet area” for soft tissue sarcomas and rarely become symptomatic until they are extremely large. Traditionally, low- and high-grade soft tissue sarcomas of the buttock were treated with a posterior cutaneous flap hemipelvectomy.

Advances in limb-sparing surgical procedures have permitted resections with safe margins in most sarcomas and have reduced the need for hemipelvectomy for tumors in this region.

Tumors of the gluteus maximus are often confined to this muscle and do not extend to the underlying retrogluteal space or involve the sacrum or femur. The most significant structure in the retrogluteal space that must be evaluated is the sciatic nerve. Minimal reconstruction is required.

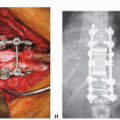

During the postoperative period, it is important to take measures to prevent the formation of large postoperative seromas. The functional outcome of a resection of the gluteus maximus is a minimal deficit in hip extension only. The gait is normal.

A hemipelvectomy rarely is required for a soft tissue sarcoma of the buttock unless it is extremely large or accompanied by fungation, infection, or extension into the ischiorectal space, pelvis, and hip. Direct sacral or iliac bone involvement, which is rare, often necessitates an amputation.

About 90% of soft tissue sarcomas arising in the buttock can be resected and treated adequately by a limb-sparing surgery. Low-grade soft tissue sarcomas of the gluteus maximus usually require surgery only; high-grade soft tissue sarcomas in this region, like those in other anatomic areas, are also usually treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation preoperatively and/or postoperatively.

A small group of selected patients with high-grade sarcomas in the buttock area received induction chemotherapy. The field is treated with postoperative radiation if it is required.

The major indications for an amputation are extremely large sarcomas that involve the adjacent bone, the sciatic nerve, or the ischiorectal fossa.

ANATOMY

The gluteus maximus arises from the sacral lamina, iliac crest, and ischium. It passes obliquely to its insertion onto the proximal portion of the iliotibial band. This insertion begins above the greater trochanter, passes 4 to 5 cm below the greater trochanter, and then attaches to the adjacent femur.

The area underneath the gluteus maximus is termed the retrogluteal space. This area consists of the posterior hip musculature, including the external rotators and portions of the gluteus medius muscle. The sciatic nerve lies in the retrogluteal space.

The gluteus maximus does not attach to the retrogluteal structures as it passes over them. This permits easier surgical dissection of the retrogluteal plane and preservation of the sciatic nerve in many situations.

As it passes from the sacrum to the femur, the gluteus maximus covers the sacroiliac joint and the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments as well as a portion of the ischiorectal fossa.

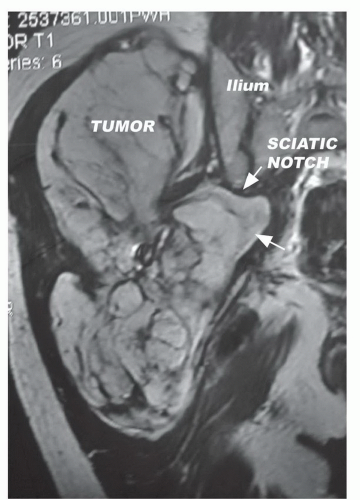

Most importantly, the sciatic nerve exits the pelvis through the sciatic notch (FIG 1) and passes inferiorly to the piriformis muscle. This nerve is identified in the halfway distance between the ischial tuberosity and greater trochanter and lies in close proximity to the posterior fascia of the gluteus maximus; therefore, large tumors of the gluteus maximus may involve the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve, however, rarely is involved by the tumor; most often, it is displaced around the capsule or pseudocapsule. The inferior gluteal vessels pass below the piriformis muscle to enter the midportion of the gluteus maximus. The inferior gluteal vessels are routinely ligated.

INDICATIONS

A gluteus maximus resection is indicated for patients with lowand high-grade sarcomas confined to the gluteus maximus.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Large tumors that involve the true pelvis or ischiorectal space

Involvement of the sacrum or ilium

Sciatic nerve involvement (although, on occasion, the sciatic nerve may be resected)

Pelvic extension through the sciatic notch

IMAGING STUDIES

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are most useful in determining the extent of tumor involvement of the gluteus maximus

Close evaluation determines the involvement of the adjacent sacrum, femur, and sciatic nerve. Attention should be placed on the evaluation of the structures of the retrogluteal space, including the hip joint and sciatic nerve, and ischiorectal fossa. Buttock tumors may extend into the pelvis through the sciatic notch (FIG 2).

Bone and Positron Emission Tomography Scans

Tumor involvement may extend to the crest of the ilium, the sacrum, and the proximal femur. These areas should be evaluated by bone scintigraphy. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan is useful in determining the anatomic soft tissue extension of buttock tumors (FIG 3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree