I. INTRODUCTION

The chapter focuses on illnesses associated with indoor exposures. The term building-related illness (BRI) originated after health complaints associated with indoor working environments—primarily office buildings—became prevalent in the 1970s and the 1980s. The term was developed to contrast with “sick building syndrome (SBS)” (see below) in which nonspecific complaints are prevalent and a clear pathophysiologic basis has not been identified. Other sections of this book focus on the specific allergens present in indoor environments and the more typical allergic symptoms they cause. While some BRIs are related to specific allergen exposures, other factors that may be more difficult to ascertain are also thought to play a significant role in BRI.

The chapter highlights nonoccupational exposures and includes residential and office environments. Patients with suspected building-related complaints may seek the advice of a primary care doctor, allergist/immunologist, toxicologist, or occupational health clinic. Therefore, the chapter draws from the literature from those specialties. However, we highlight exposures and diagnoses of interest to the practicing allergist/immunologist.

In addition to typical allergens like dust mites or animal danders, there are multiple additional features of the indoor environment relevant to human disease. The one that has garnered the most attention in the press is the presence of fungi or mold, particularly related to damp indoor spaces. However, there are other features of the indoor environment of potential significance, especially including the presence of other allergens and irritants such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The exact role of all of these components in BRI has not been fully elucidated.

The following mechanisms of BRI have been described: immune, infection, intoxication (mycotoxicity), and irritation (

Table 23-1). In addition to discussing specific BRI, we review practical issues related to BRI including related syndromes, key components of the medical history and physical examination, and the interpretation of reports of environmental assessments.

A. Sick Building Syndrome/Irritant Syndromes

The term sick building syndrome (SBS) was introduced in the 1970s after a high prevalence of complaints was reported in workers in newer office buildings that did not have natural ventilation. Over the years, several definitions for SBS have been used. Further, some of the features of what was originally referred to as SBS have been determined to have a pathophysiologic basis and are now considered BRIs.

Today, SBS generally refers to medical symptoms with an unclear cause that have a possible relation to the indoor environment. According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) definition, SBS occurs when

building occupants complain of symptoms associated with acute discomfort, for example, headache; eye, nose, or throat irritation; dry cough; dry or itchy skin; dizziness and nausea; difficulty in concentrating; fatigue; and sensitivity to odors. Most of the complainants report relief soon after leaving the building. The cause of SBS is unknown (

Table 23-2).

Depending on the definition used, symptoms can include neurobehavioral symptoms (e.g., memory loss, headache, depression, dizziness) and complaints involving the eyes (irritation, pain, redness), skin (rashes, dryness, pruritus), and upper airways (congestion and rhinorrhea). The pathophysiologic mechanisms explaining how environmental factors cause SBS remain elusive, although SBS has been associated with lower ventilation rates.

B. Multiple Chemical Sensitivity

Multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS), or idiopathic environmental intolerance (IEI), is an acquired chronic disorder characterized by multiple recurrent symptoms that affect different organ systems. Patients consider it to be caused by exposure to low levels of environmental chemicals, which are at a well-tolerated concentration for the majority of the population. The definition of MCS can vary between authors, and the cause of MCS-IEI is unclear. The study of

Dalton and Jaén (2010) suggests that MCS patients have differences in cognitive processing of odors rather than differences in sensitivity or susceptibility to chemicals.

II. PATIENT EVALUATION

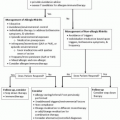

Like with all patient encounters, a comprehensive medical history and thorough physical exam should be undertaken. A possible link between exposure and symptoms may be established on the basis of observation and correlation.

A. History. It is advisable to search for a change in the environment related to symptom onset or exacerbation, rather than seeking information on specific

exposures. It is important to elicit specific symptoms as well as the timing of those symptoms in relation to presence in the home or work environment (

Table 23-3). Did the symptoms begin after starting a specific job or moving into a new location? Do the symptoms abate over the weekend or while on vacation? Do they progress throughout the day? Are they worse at home or at work? Do they come on immediately, or gradually? Do they resolve with leaving the building, or over a longer period of time? Are other individuals in the building experiencing similar symptoms? The history should also include some information about the work organization and factors such as job satisfaction, level of stress, and relationships with coworkers and supervisors.

B. Examination. A thorough physical examination should be performed. Patients with building-related symptoms may have important physical findings, such as conjunctival injection, turbinate edema, urticaria, eczema, or an abnormal pulmonary exam. Further, patients with rheumatologic or other multisystem disease may initially attribute their symptoms to the indoor environment and present to an allergy/immunology clinic.

C. Assessment of Home/Work Environment. It is important to elicit specific characteristics of the home and work environment (

Table 23-4). What is the patient’s job? Are there specific chemical or allergen exposures at work? Is there a damp area? Has the area been flooded? Is there visible mold? What is the heating/cooling system? What structures are nearby? Has any building inspection been done for mold/bacteria? Have there been any recent changes to the home or work environment?

D. Laboratory Evaluation. Additional investigations including laboratory and radiologic may be relevant depending on the history and physical

examination findings and the differential diagnosis in question. Assessment for IgE antibodies to mold antigens has clearly been validated as a measure of potential allergic reactivity to mold. However, as with all allergy testing, a positive skin test or specific IgE antibody to molds or other allergens without appropriate clinical evaluation should not be taken as an indicator of clinical disease. In addition, the presence of IgE antibodies to an allergen cannot be used to determine the dose or timing of prior exposures.