Breast cyst

Breast development

Breast imaging

Fibroadenoma

Galactorrhea

Gynecomastia

Macromastia

Mastalgia

Mastitis

Prolactinoma

TABLE 55.1 Common Breast Complaints in Female Adolescents | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Polythelia: accessory nipple; the most common congenital breast anomaly in males and females. Not associated with other congenital anomalies

Polymastia: presence of accessory breast tissue along the milk line

Supernumerary breast: presence of a nipple and underlying breast tissue. May be associated with renal anomalies

TABLE 55.2 Historical Features Key to Evaluate Breast Complaints in Adolescent/Young Adult Females | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

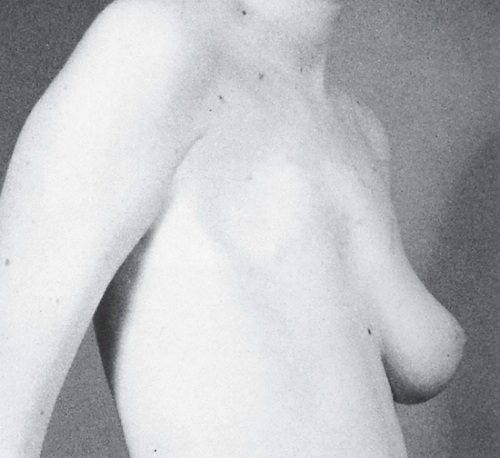

Amastia, absence of breast tissue, results from complete involution of the mammary ridge. Amastia is a rare, usually unilateral abnormality. Iatrogenic amastia can occur if the developing breast undergoes surgical procedures such as biopsy. Poland syndrome presents with amastia, ipsilateral rib anomalies, webbed fingers, and radial nerve palsies. Amastia can be extremely disturbing to adolescents and young adults (AYAs), but can be surgically corrected (Fig. 55.1).3 Athelia is the absence of the nipple on one or both sides, and can be corrected surgically.3

Clinical manifestations: Physical complaints include back and shoulder pain, postural changes, breast discomfort, mood disturbances, intertrigo, and limited ability to participate in physical activity. Adolescents are also concerned about self-image, difficulty finding clothing that fits, and unwanted social attention.

Diagnosis: Evaluation should include a thorough examination and ultrasound if needed to rule out any underlying mass.

Management: Patients should be fit for a supportive, comfortable bra. Weight loss may help to improve symptoms for obese patients. For persistent symptoms, reduction mammoplasty is performed in adolescents who have completed breast growth to prevent the need for a second procedure. Adolescents report a high rate of both satisfaction and symptom relief following surgery.6 Patients should be referred to a plastic surgeon with experience in treating teens, and who are sensitive to the teens’ particular body image concerns.

(worse immediately before menses) or noncyclic pain (mastodynia). Common causes include premenstrual fibrocystic changes, exercise, infection, early pregnancy, or medications such as oral contraceptives. The evaluation should include a breast assessment and a pregnancy test. Once the diagnosis of mastalgia or mastodynia has been made, treatment includes analgesics (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), good bra support (both night and day if needed), and reassurance. Most breast pain resolves spontaneously within 3 to 6 months. Oral contraceptives may improve or worsen breast pain, possibly in a dose-related manner. Evening primrose oil and vitamin E have shown some efficacy in small trials.

Clinical manifestations: Constitutional symptoms (malaise, fever) may occur. Physical examination reveals an edematous erythematous breast, possibly with purulent discharge (Fig. 55.3). A discrete abscess may be palpated as an area of fluctuance.

Diagnosis: Any purulent breast drainage or nipple discharge should be sent for culture. Abscess can be confirmed with ultrasound if necessary.

Management: For simple mastitis, treat with antibiotics for 7 to 10 days and warm compresses. Antibiotic therapy should be targeted at the most likely pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus, streptococci, enterococcus). Dicloxacillin or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid provides adequate coverage of skin pathogens. For penicillin-allergic patients, clindamycin is a good choice. If patients are breast-feeding, expression of milk from the affected side should continue to prevent milk stasis. Infants can continue breast-feeding from the affected side.

Abscess: Patients should be reexamined within several days to confirm response to therapy. Persistent infection despite antibiotic therapy should be evaluated with re-examination of the breast and ultrasonography for an underlying abscess. Abscess drainage can be attempted in the office with a large-bore needle. If needle aspiration is unsuccessful or if the abscess re-accumulates, the patient should be referred for incision and drainage. Incisions should be as small as possible to limit resulting distortion. Material obtained at aspiration or incision and drainage should be cultured. Infections that fail to respond to adequate antibiotic therapy should also be referred for surgical management. These patients should be screened for underlying immunosuppressive disease that may interfere with their ability to clear the infection, like diabetes mellitus or human immunodeficiency virus infection.

Contact dermatitis: Local contact dermatitis of the nipple can give rise to serous, purulent, or bloody discharge. Culprits include soap, clothes, clothing detergent, or lotion used by the patient. Treatment is identification and discontinuation of the offending agent, with topical steroid cream for symptom relief.

Infection: Purulent discharge indicates infection. Culture the discharge, and treat with appropriate antibiotics and warm compresses. If the infection fails to respond to antibiotic therapy, incision and drainage may be indicated.

Montgomery tubercles: The periareolar glands of Montgomery will occasionally drain fluid through ectopic openings on the areola. Discharge is usually serous or serosanguinous. Ultrasound can confirm the clinical suspicion through visualization of the retroareolar cyst. Discharge will resolve spontaneously.

Mammary duct ectasia: Ductal ectasia refers to dilation of the mammary ducts as well as periductal inflammation. No clear etiology is known. Discharge is usually serous or serosanguinous. Ultrasound can confirm the diagnosis. Treatment includes reassurance and supportive care; mastitis risk may be slightly increased.8

Intraductal papilloma: These rare, benign, proliferative tumors often present with bloody discharge from a single duct. They represent a focal hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium invaginating into the duct on a vascular stalk. Disruption of this stalk leads to the bloody discharge. If the proliferation of duct epithelium grows large enough, it creates a palpable mass. Although an infrequent finding in AYAs, a palpable mass associated with a bloody nipple discharge has a 95% probability of being an intraductal papilloma, even in teens. Ultrasound and potentially ductogram should be performed. Any abnormality found should be excised. Bloody discharge is usually not related to underlying carcinoma in the AYA age-group.

Hypothalamic and infundibular lesions, including craniopharyngiomas, infiltrative disorders, and damage to the

infundibulum from surgery or head trauma (inhibition of counterregulatory dopamine release)

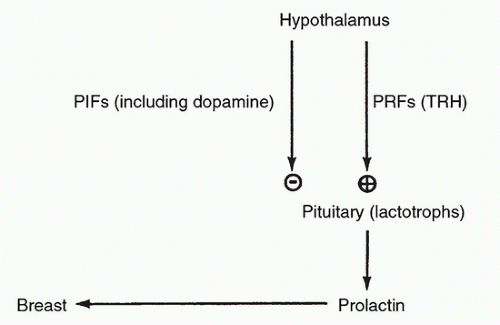

FIGURE 55.4 Schema of prolactin control. PIF, prolactin-inhibiting factors; PRF, prolactin-releasing factors; TRH, thyrotropin-releasing hormone.

TABLE 55.3 Medications Causing Hyperprolactinemia

Antipsychotics

Antihypertensive agents

Risperidone

Verapamil

Olanzapine

α-Methyldopa

Butyrophenones (haloperidol)

Reserpine

Phenothiazines

Gastrointestinal medications

Antidepressants

Metoclopramide

Tricyclic antidepressants

Domperidone

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Other medications

Opiates and opiate antagonists

Estrogens

Anesthetics

Anticonvulsants

Antihistamines (H2)

Dopamine-receptor blockers

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree