The beginning of breast conserving therapy (BCT) coincides with the early days of clinical radiotherapy. Geoffrey Keynes, a London surgeon, practiced breast conserving surgery combined with radiotherapy in the 1920s, and Vera Peters, a Toronto radiation oncologist began using a similar approach in the 1930s.1–4 The results, in terms of overall survival, were comparable to contemporaneous radical surgical results. However, this was likely in large part a result of advanced disease at presentation and the lack of any or adequate systemic therapies, resulting in equivalent rates of death that occurred before progression or recurrence of local disease.

In the 1970s, newer hypotheses emerged regarding the nature of breast cancer, which suggested that patient outcomes (i.e., survival) were dependent on metastatic disease present (or not) at the time of diagnosis. This led to several clinical trials designed to determine whether BCT would provide equivalent outcomes to total mastectomy in women with “early” breast cancer. In Italy, a prospective randomized trial compared modified radical mastectomy to removal of the breast quadrant containing the tumor (“quadrantectomy”) with axillary node dissection plus radiation therapy to the breast.5–7 In the United States, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) investigators, led by Dr. Bernard Fisher, carried out a trial (B-06) with a more conservative local excision (“lumpectomy”) requiring just a negative margin (“no ink on tumor”), with or without breast irradiation, compared to total mastectomy.8–10 Both trials demonstrated equivalent DFS and OS for BCT and total mastectomy, which persisted for more than 20 years of follow-up. A number of other prospective randomized trials confirmed equivalent outcomes for BCT and total mastectomy.11–14 And in 1990, an NIH consensus statement declared “Breast conservation treatment is an appropriate method of primary therapy for the majority of women with stage I and II breast cancer and is preferable because it provides survival equivalent to total mastectomy and axillary dissection while preserving the breast.”15

From the 1980s until 2000, especially following release of the 1990 NIH consensus conference statement,15 there was a steady rise in the proportion of women undergoing BCT versus mastectomy in the United States.16–18 However, there were some clear geographic, socioeconomic, and provider differences in this trend, with some parts of the country lagging behind.

In the last two decades, however, several centers have noted reversal of this trend, with more women undergoing unilateral and bilateral mastectomies.19–21 While some have cited increasing use of MRI, the reasons are not entirely clear, and a national survey did not confirm this trend for the United States as a whole.22–25 Some of the factors that may contribute to increased total mastectomy rates include new and better methods of reconstruction, desire for symmetry, freedom from further screening exams, and exaggerated patient perceptions of the risks for local recurrence for both BCT and contralateral breast cancer.

Concise reviews of the factors impacting who should or should not be considered for BCT have recently been published.26,27 There are a very limited number of true contraindications to BCT for cancer, as listed in Table 77-1. However, some of these have recently been challenged, including the presence of multicentric disease and tumor to breast size ratio. A clinical registry trial of the Alliance cooperative group (Alliance 11102) is currently accruing patients who undergo excision of two separate sites of cancer in the same breast, followed by radiation. Inability to receive breast irradiation (e.g., because of travel distance and difficulty with transportation or a history of connective tissue disease that may increase the toxicity of radiation) is generally considered a reason to avoid radiation. For older patients with small tumors, however, prospective trials suggest that local recurrence rates may be slightly higher without radiation, but that overall recurrence rates and survival may be acceptable without irradiation.28–30 For tumors that are too large to achieve a good cosmetic result at the time of presentation, neoadjuvant systemic treatment and oncoplastic methods may reduce the need for total mastectomy (see more detail on these below). Perhaps the only remaining “absolute” contraindications to BCT going forward will be inability to attain negative margins despite repeated excisions and extensive invasive cancer or duct carcinoma in situ (DCIS) involving more than 1/3 of the breast (depending on breast size). Many unnecessary total mastectomies have been and are likely still being performed for “pseudo-contraindications” that are not really well-founded. These are also listed in Table 77-1. Although presence of an “extensive intraductal component” (EIC—defined as ≥ 25% of the extent of disease consisting of DCIS with an additional separate focus on DCIS) was shown to be a risk factor for ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) in an early study from the Harvard Joint Center for Radiation Therapy, these results came from a cohort of patients in whom attention to clear margins was not strictly adhered to, and subsequent analysis of this feature has not confirmed it to be a contraindication to BCT.31–36 The pathologic description of “multifocal” cancer, which implies that there are microscopically separate islands of invasion within a single lesion, has often apparently been misunderstood as being the same as “multicentric” cancer (which should be used to refer to separate sites of cancer in different areas of the breast), resulting in unnecessary mastectomies. Patients have also undergone mastectomy based on either being too young or too old for BCT. Advanced age really should have no impact on this decision, since these patients are excellent candidates for BCT, and may be just as desirous of breast conservation as younger women. And, while it has been found consistently that younger women are at higher risk for IBTR after BCT, they are also at higher risk for other types of recurrence and for local recurrence after mastectomy. As for older women, overall survival is the same regardless of local treatment for women under 40 years of age.37–45

Role of Clinical Factors in Decision to Offer BCT

| NON Contraindications to BCT | Relative Contraindications to BCT | Absolute Contraindications to BCT |

|---|---|---|

| Extensive intraductal component | Multicentric disease | Diffuse disease (e.g., malignant calcifications or biopsy-proven diffuse cancer found on MRI) |

| High grade | Prior breast irradiation | Inability to achieve negative margins |

| Positive nodes | Radiation therapy inaccessible | PATIENT CHOICE |

| Large breast | First trimester of pregnancy | |

| Small breast | Large tumor relative to breast size—can be overcome by neoadjuvant systemic therapy and/or oncoplastic methods | |

| Patient age (too young or too old) | Connective tissue diseases (e.g., scleroderma or systemic lupus involving skin) | |

| Multifocal disease | ||

| Central location/nipple involvement | ||

| Second or third trimester of pregnancy |

Centrally located lesions that involve the nipple, including Paget’s disease of the nipple, used to be considered indications for total mastectomy because of the need to remove the nipple-areolar complex to achieve complete excision. But the facts that reconstruction after mastectomy also results in a breast mound without a nipple and that many women opt not to have the nipple-areolar complex reconstructed, made us aware that preservation of a breast mound without a nipple might be acceptable to many women. This has led to the frequent use of BCT requiring removal of the nipple (Fig. 77-1). Large breasts have also caused some overuse of total mastectomy because of the concern about more severe radiation reactions in fatty breasts and the potential for asymmetry. More modern radiation techniques, and perhaps the selective use of accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI), have made this less of a concern. For some women with very large breasts, the approach of using a breast reduction/mammoplasty procedure for resection of the cancer, along with the reduction of the contralateral breast to achieve symmetry, has resulted in results that these patients find highly satisfactory and may reduce the problem of severe skin reactions that are seen when irradiating very large breasts (see Fig. 77-2A, B).

At one time, it was considered standard of care to perform total or modified radical mastectomies for women with breast cancer presenting during pregnancy, largely based on concerns about the impact of radiation to the developing fetus.26,46 More recently, however, it has become clear that this is not always necessary. Most of these young women require adjuvant chemotherapy and certain chemotherapy drugs (including anthracyclines and cyclophosphamide but excluding methotrexate) can be administered safely during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.47,48 Thus, women who are past the first trimester at the time of diagnosis can either receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery or can have primary breast conserving surgery, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy during pregnancy, allowing radiotherapy to be delayed until after delivery.

Magnetic resonance imaging has become increasingly common as a part of the evaluation of women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. MRI may detect otherwise undetectable contralateral cancers in 3% to 5% of women with cancer in one breast.49,50 A number of retrospective studies have also demonstrated that MRI scans detect additional sites of disease in the ipsilateral breast, leading to modification of the surgical plan (e.g., wider excision or change to total mastectomy) for a significant proportion of women presenting with clinically solitary lesions and for whom BCT was planned.51–57 On the other hand, a large retrospective study from University of Pennsylvania found no improvement in re-excision rates or IBTR rates for women undergoing MRI compared to those who did not.58 Two large prospective randomized trials of MRI versus no MRI failed to show any decrease in re-excision rates or local recurrences, although follow-up remains short.59–61 Recent analysis of data from Northwestern found that MRI increased the likelihood of additional biopsies in patients with DCIS.62 In a separate series of DCIS patients from Memorial Sloan Kettering, there was no significant difference in local recurrence rates at a median follow-up of nearly 5 years for women with DCIS who had an MRI prior to surgery (8.5%) versus those who did not (7.2%).63 They also reported no difference in the occurrence of contralateral cancers. Of course, this study and others like it, even with adjustment for many factors known to impact IBTR, can be influenced by patient selection. A recent meta-analysis of studies comparing MRI to no MRI found that having an MRI increased the likelihood of a complete mastectomy, and that there was not any clear-cut clinical benefit associated with its use.23 Although it is hard to reconcile the lack of impact of finding other sites of disease with “squabbles” about how wide a margin is adequate, the answer likely lies in the effectiveness of radiation, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy at eliminating or suppressing other foci of cancer that might be present at the time of diagnosis so that they never become clinically evident.

Although the original criterion for an acceptable negative margin in the NSABP’s prospective randomized trial that demonstrated that BCT was equivalent to total mastectomy was that there be “no tumor on ink,” there has been a great deal of debate recently over what distance constitutes an adequate margin for segmental mastectomy. Various authors have advocated minimum acceptable margins of 1, 2, 5, or even 10 mm, which has led to a wide range of frequency of second operations to achieve “better” margins, even when the initial excision margin does not have tumor cells at the edge of the resected specimen.64–66 This has usually been supported by data showing that pathologic examination of breast tissue re-excised for “close” margins frequently finds additional microscopic cancer.67 But this should come as no surprise, since Holland et al68 showed many years ago that careful pathologic assessment found additional sites of cancer more than 2 cm away from the index cancer in 43% of the specimens. Re-excisions, including secondary total mastectomies have been reported to be from 20% to 70% from some centers.69–72 Extensive review of the literature, however, does not confirm that re-excision for close margins improves local control.73–75 In fact, despite the data showing microscopic disease at significant distances from the known cancer, local control rates with “no tumor on ink” have been excellent with the addition of radiation.35,76–78 Improvements in systemic adjuvant therapy have further decreased the observed rates of local in-breast recurrence along with improved distant disease-free survival.79 IBTR percentage rates now are generally in low single digits, even at 10+ years. Local recurrence rates have also been shown to be impacted by the biologic subtype of the cancer, including hormone receptor status, HER-2 status, and molecular profile within the subset of hormone receptor positive cancers.42,80 We have reviewed our own experience recently, and have only performed re-excisions in 15.5% of our patients initially undergoing partial mastectomy for a cancer diagnosis. Re-excisions were performed only for “tumor on ink” positive margins and occasionally for tumor being less than 1 mm extensively or at multiple margins. Despite this, the long-term recurrence rate was only 3.4%.81 The recurrence rate was actually higher in women who underwent re-excision, likely reflecting more aggressive biology. This agrees with other studies showing no impact of re-excision for close margins.73,82 Other groups have also reported that the distance of the cancer cells from the surgical margin had no impact on IBTR rates, as long as the margins were negative.75,77,83 A consensus panel organized by the Society of Surgical Oncology and the American Society for Radiation Oncology recently considered all of the available data on margins and margin width, and after performing a meta-analysis of these data, determined that there was no evidence for improved outcomes with margins wider than “no tumor on ink.”74 The practical implication of this conclusion is that surgeons should not perform secondary re-excisions or mastectomies to improve on negative margins that are perceived as not wide enough. (Level of evidence—meta-analysis and retrospective studies.) Re-excisions for “close” margins unnecessarily increase patient anxiety, compromise cosmetic outcomes, may result in more total mastectomies, and may lead to delays in adjuvant regional and systemic therapy.

The quest for negative and wider margins has also led to a number of intraoperative strategies to decrease the need for secondary re-excisions. These include mammographic assessment, intraoperative ultrasound, frozen section pathology performed on either the edges of the resected specimen or on “shaved” samples of the cavity margins, cytologic examination of imprints from the edges of the specimen, and probes that can detect the presence of residual malignant cells in the edges of the specimen or cavity.84–95 However, to the extent that these are done to prevent “close” margins, their value is doubtful, and there has not been any clear advantage demonstrated in terms of lower IBTR rates. Other alternatives to intraoperative pathologic confirmation of negative or adequate margins have also been advocated. In addition to routine assessment of the lumpectomy specimen or the remaining cavity, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the cavity walls has been suggested as a way to destroy any remaining cancer cells, and has also been hypothesized as a replacement for postlumpectomy irradiation.85 A trial to assess this more carefully is under way. Recently, a single institution randomized trial demonstrated that routine shaving of the lumpectomy cavity margins reduced the rate of positive margins from 34% to 19% and the incidence of re-excision from 21% to 10%. However, as yet, this has not been shown to impact the incidenc of IBTR.

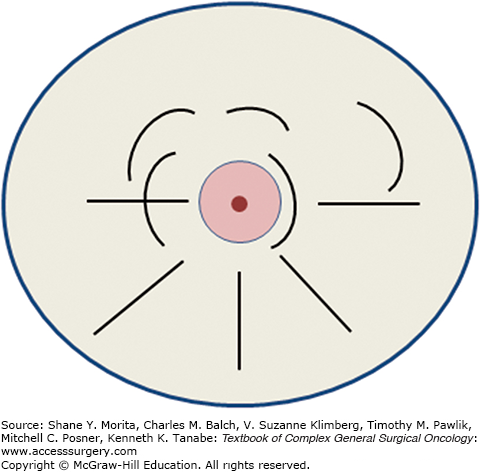

The ideal classical or standard recommended incisions for segmental mastectomy are illustrated in Fig. 77-3. In general, curvilinear incisions parallel to the areola should be used for tumors in the upper quadrants, and radial incisions generally result in better cosmesis for resection of tumors in the lower quadrants. This is at variance from recommendations by others, who recommend arcuate incisions in all quadrants. However, we have found that transverse incisions in the lower half of the breast result in folding of the breast and inferior cosmetic results. At the level of the nipple (i.e., 3 and 9 o’clock), either approach may be satisfactory. Incisions along the areolar border result in generally excellent cosmesis and are fine for lesions that are adjacent to or directly behind the areola, but should not be used to approach remote lesions that might be malignant. It needs to be borne in mind that the final shape and position of the incision and defect may be different from the way they appear in a supine patient on the operating table versus the appearance when the patient is upright. Whether or not to reapproximate the defect in the breast tissue is a subject of some controversy. In largely fatty replaced breasts, the cavity will usually collapse on itself over time, but in some patients, a chronic seroma cavity may result, which can be quite troublesome to the patient and the physicians following her. On the other hand, reapproximating the breast tissue may cause dimpling and distortion of the surrounding breast and skin if measures are not taken to mobilize the breast tissue, as is done in more complex oncoplastic approaches (see below). One advantage of leaving the cavity open is that it may be used for APBI methods that depend on intracavitary insertion of a device to allow delivery of a focused radiation dose (see below).

Over the past two decades, a number of techniques have been described that can be used to improve the cosmetic outcome of breast conservation surgery over that obtained with “standard” lumpectomies. In addition, this may allow for removal of a larger amount of tissue and thus may extend BCT to patients who otherwise might require a mastectomy. These oncoplastic breast surgery (OPBS) techniques, which can be divided into two general classes, volume displacement and volume replacement, have been extensively reviewed.86–93 A recent systematic review by Haloua et al94 concluded that, while this approach may be useful to avoid mastectomy in patients with tumors that are large compared to breast size, data on long-term recurrence rates are sparse, and there have been no prospective trials comparing these approaches to standard lumpectomy. Nevertheless, we and others have found that for selected patients, OPBS results in markedly improved cosmesis. This is especially true for inferior lesions, lesions near the areola, and for women with very large ptotic breasts. There are many case series in the literature that document the utility of this approach, a low incidence of positive margins and, at least in the short term, low IBTR rates and excellent cosmetic outcomes.89–94

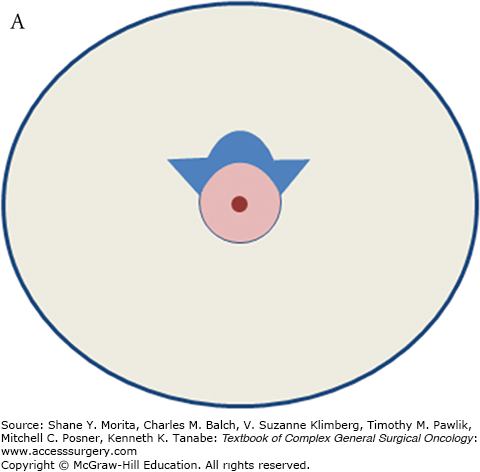

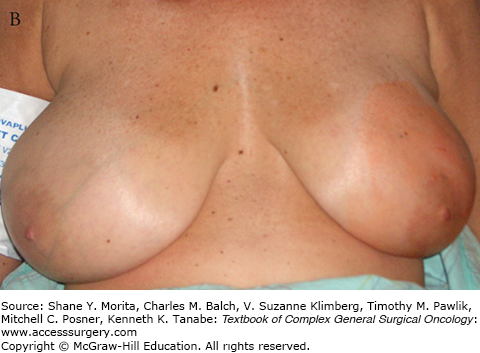

Detailed descriptions of all of the oncoplastic approaches to tumors in different locations is beyond the scope of this chapter, but they vary from simple methods such as “batwing” incisions (Fig. 77-4A to E) that minimize the “dog-ear” effects of removing skin with the breast tumor, to more complex procedures that may require collaboration from plastic surgeons.95 Clearly, volume replacement methods, such as latissimus dorsi flaps would fall into the latter category.

FIGURE 77-4

A. Schematic of “batwing” incision for segmental mastectomy. Blue shaded area shows skin removed with underlying breast tissue. B. Preoperative picture; palpable tumor mass was in upper central left breast prior to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. C. Incisions, including modified version of “batwings” to avoid “dog-ears” and ensure adequate anterior margin. D. Closed incision after segmental mastectomy. E. Final result after irradiation, 15 months after surgery and 22 months after diagnosis.

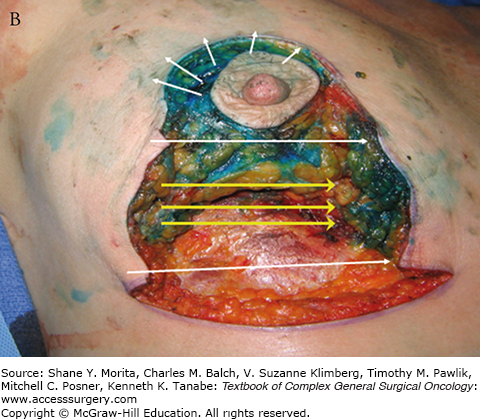

We have found OPBS to be particularly useful for cancers in the inferior quadrants of the breast, where simple excision, especially if done through a transverse incision may result in a “bird’s beak” deformity (Fig. 77-5), with a fold in the breast and distortion of the nipple orientation.96 A procedure similar to a reduction mammoplasty and mastopexy, as illustrated (Fig. 77-6A to E), allows reapproximation of the breast tissue and moves the nipple-areolar complex superiorly to avoid having it point down when the breast has healed. In contrast to the usual appearance after resection of inferior breast tissue, the treated breast has a normal shape and nearly equal size to the contralateral breast (Fig. 77-6D). If necessary, symmetrizing surgery can be performed on the contralateral breast, although this might be better delayed until after radiation therapy and other adjuvant therapy to wait for the final size and shape of the treated breast to be clear.

FIGURE 77-5

Typical “bird-beak” deformity resulting from inferior segmental mastectomy. (Reproduced with permission from Holmes DR, Silverstein MJ: Triangle resection with crescent mastopexy: an oncoplastic breast surgical technique for managing inferior pole lesions, Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 Oct;19(10):3289-3291.)

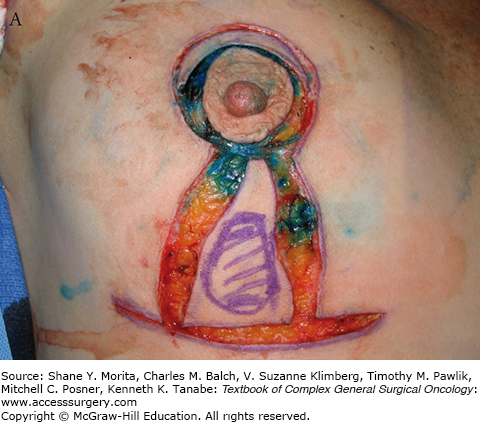

FIGURE 77-6

A. Incisions for inferior triangle resection of tumor (outlined in purple marker) using mammoplasty approach. B. After removal of cancer, showing directions for superior displacement of the nipple areolar complex and reapproximation of breast defect and skin. C. Intraoperative result after closure. D. Results 11 months postoperatively and after chemotherapy and whole-breast irradiation. E. A different patient resected and reconstructed using a similar oncoplastic approach, 4 months after surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree