In the USA, 80% of patients with breast cancer are treated by community breast surgeons. NCDB data indicate that there are only small differences in outcomes between lower volume cancer programs and higher volume programs. There is some evidence that breast cancer patients of high-volume breast focused surgeons may have improved outcomes. This article discusses the challenges community breast surgeons face and some ways that the quality of care could be monitored and improved. Quality reporting programs of the Commission on Cancer and Mastery of Breast Surgery Program of the American Society of Breast Surgeons are recommended as tools to track and improve outcomes in breast cancer care.

According to the World Health Organization, breast cancer comprises 22.8% of all cancers in women worldwide. In the United States, 80% of patients with breast cancer are treated by community breast surgeons. This article discusses the challenges community breast surgeons face and some of the ways that the quality of care delivered could be monitored and improved.

An increasing body of literature suggests that there are, between hospitals of different sizes and resources, disparities in outcomes of cancer care. Our examination of the problem of disparities in breast cancer outcomes is framed by the Donabedian paradigm of the 3 domains of quality assessment: structure, process, and outcomes. The goal of all our quality improvement efforts as health care providers is to improve the outcomes for communities and patients.

Drs Bleznak and Kennedy and Mr Stewart and Mr Palis begin this article with an analysis of clinical process and outcomes data from the Commission on Cancer (CoC). They compare and contrast performance among hospitals in different categories of CoC accreditation. The hospitals in the CoC program treat 70% of patients newly diagnosed with cancer in the United States. Also, in the domain of outcomes assessment, Dr Bailey reviews the performance of breast surgeons according to the volume of patients with breast cancer treated. She presents evidence supporting the premise that breast-focused, high-volume breast surgeons achieve better outcomes for their patients.

In the domain of process, Dr Laidley describes the ways the American Society of Breast Surgeons is working to improve the quality of breast cancer care in the United States through its Mastery of Breast Surgery Program. In the domain of structure, Drs Penman and Dickson-Witmer relate the way a community cancer center has worked collaboratively with a mix of hospital-based, employed, and private practice physicians to develop a multidisciplinary breast program with continuous processes of quality improvement. In a separate article of this issue, Dr Winchester describes the ways that all 3 domains of quality are addressed by the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers with the goal of improving breast cancer care across a broad spectrum of delivery environments.

An analysis of performance among cancer programs in different categories of CoC accreditation

The Mission of the CoC

The CoC, established in 1922 by the American College of Surgeons, is a consortium of more than 100 individuals representing more than 50 national professional organizations. The commission’s efforts are designed to improve the quality of cancer care in all categories of cancer programs, so that patients may receive the highest quality of care, with the greatest possible probability of cure, without leaving their local commission-accredited cancer program (of which there are >1500 in the United States).

The commission improves the quality of cancer care by establishing standards for multidisciplinary care, outreach efforts, quality of cancer data collected, and use of information about each institution’s treatments and outcomes as measured against nationally recognized benchmarks. Just more than 70% of patients newly diagnosed with cancer in the United States receive all or part of their care in a CoC-accredited program each year. The commission accredits more than 1500 cancer programs in the United States, surveying each program every 3 years to evaluate compliance with 36 standards. Patient-level data from accredited programs are reported to the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) of the CoC following nationally standardized data collection processes and transmission protocols. These data are compiled in the largest cancer database in the world, housing information on demographics, disease site, stage, treatment, and survival for more than 26 million patients. The NCDB, a joint program of the American College of Surgeons’ CoC and the American Cancer Society, is the data source used in this article for the examination of similarities and differences between cancer programs of different types regarding surgical treatment of women with breast cancer, performance on the CoC’s breast-related quality-of-care indicators, and survival of patients with breast cancer.

For purposes of this article, patients with breast cancer in the NCDB were identified by the topography code C50.X according to the International Classification of Disease-Oncology third edition. Hospital cancer registries abstracted cases with the Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards manuals, a standardized set of data elements and definitions, using information provided by both patients and hospital medical information systems.

Patient-level data were selected from the NCDB in 2 cohorts based on the time of diagnosis. There were 319,080 patients with breast cancer registered in the NCDB between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2008. The second cohort comprised 271,328 patients with 5-year follow-up diagnosed between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2003. For analysis, both patient cohorts were limited to adult female patients older than 18 years diagnosed with either 1 malignant or the first of 2 or more malignant primaries. Aggregate-level hospital data were obtained from the Cancer Program Practice Profile Reports (CP3R), a program of the NCDB, from 1397 participating accredited facilities.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables presented in the analysis. Categorical variables were assessed for significance using the 2-sided z tests of proportional difference. Five-year overall survival rates were calculated from the date of diagnosis to death or the last follow-up. Patients diagnosed from 2002 to 2003 were evaluated for survival outcome and had a minimum of 5 years of follow-up data. Survival was estimated by the relative survival method, calculated as a ratio of observed survival over expected survival of the general US population. Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the risk of mortality on age, insurance status, race/ethnicity, ZIP code–level income, tumor grade, the Charleson-Deyo comorbidity index, hospital type, and treatment. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were generated; hazard ratio greater than 1.0 indicates an increased likelihood of death. The level of statistical significance was set at P <.05. All analyses were generated using SPSS 17.0.1 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

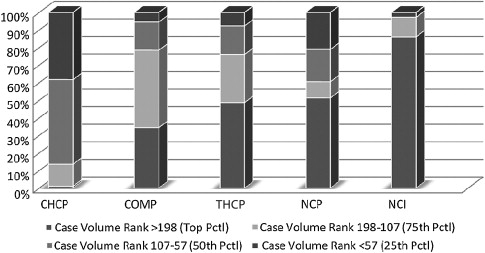

Table 1 displays some of the criteria for CoC program category designation. Seventy-two percent of programs are in 1 of the 2 community hospital categories, and just more than 20% of programs are Teaching Hospital Cancer Programs, Network Cancer Programs, or National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Comprehensive Cancer Programs. Fig. 1 displays the average annual breast cancer case volume by CoC accreditation category (for diagnosis years 2005–2007). Cancer programs have been divided into 4 groups based on quartile break points. Note that 86% of community hospital cancer programs have fewer than 106 analytical breast cancer cases annually, whereas 86% of NCI comprehensive cancer centers have more than 106 analytical breast cancer cases annually.

| CoC Program Category | Annual Newly Diagnosed Cancer Cases | Clinical Research | Residencies and Medical School Affiliation | Diagnostic and Treatment Services | Oncology Specialties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Hospital Cancer Program | 100–649 | Optional | Optional | Available but referral common for a portion of treatment | Medical staff is board certified in the major medical specialties |

| Community Hospital Comprehensive Cancer Program | ≥650 | Required | Optional | Available on site or by referral | Medical staff is board certified in the major medical specialties |

| Teaching Hospital Cancer Program | No requirement | Required | ≥4 including medical and surgical required | Available on site or by referral | Medical staff is board certified in the major medical specialties including oncology |

| Network Cancer Program | No requirement | Required | Optional | Available within network | Medical staff is board certified in the major medical specialties including oncology |

| NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center Program | No requirement | Required; basic science research required | Optional | Available on site | Medical staff is board certified in the major medical specialties including oncology |

Despite the large differences in case volume and in-house resource availability shown in Table 1 , the CoC holds community and comprehensive community cancer programs to the same set of high standards to which it holds academic and NCI centers. These CoC standards, revised every 5 to 6 years, address not only treatment planning multidisciplinary tumor boards, and data standards, but also adherence to nationally recognized treatment standards, use of College of American Pathologists’ reporting guidelines, quality improvement activities, and certification of radiation oncology facilities. There are differences in breast cancer case volume and in research and oncology subspecialty availability between CoC program categories. Two of these variables, volume and subspecialty expertise, have been suggested as factors contributing to outcomes variations for several malignancies and at times have been used as justification for recommendations for centralization of cancer care.

Demographics

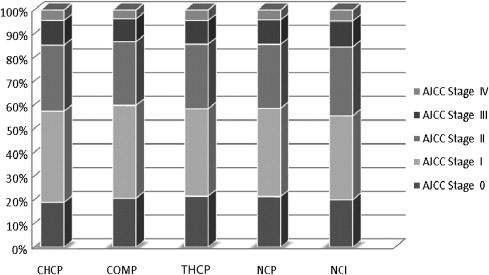

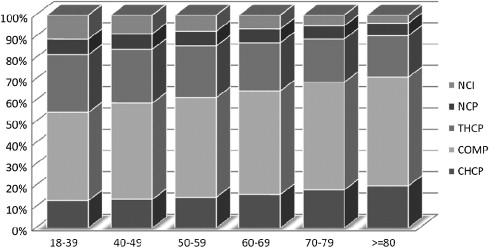

The reported comorbidities, an assessment of patients’ overall medical status as measured by the Charleson-Deyo method, and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage of breast cancer ( Fig. 2 ) did not vary across categories, but the age distribution of the women varies by program category. Younger women are more likely to present to NCI-designated, network, and teaching hospital programs ( Fig. 3 ). More than 45% of all women diagnosed between 18 and 49 years of age were treated at the 346 networked, academic, or research centers. At the NCI-designated programs, one third of patients treated for breast cancer were younger than 50 years, in contrast to 21.4% at community programs and 23.3% at comprehensive community programs.

National Quality Forum quality measures

Since 2005, the CoC has been using NCDB data to report back to programs on their performance against National Quality Forum (NQF)-endorsed quality of cancer care measures. Three of these measures relate to breast cancer care:

- 1.

Radiation therapy is administered within 1 year (365 days) of diagnosis for women younger than 70 years receiving breast-conserving surgery for breast cancer.

- 2.

Tamoxifen or third-generation aromatase inhibitor is considered or administered within 1 year (365 days) of diagnosis for women with AJCC T1c N0 M0 or stage II or III hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

- 3.

Combination chemotherapy is considered or administered within 4 months (120 days) of diagnosis for women younger than 70 years with AJCC T1c N0 M0 or stage II or III hormone receptor–negative breast cancer.

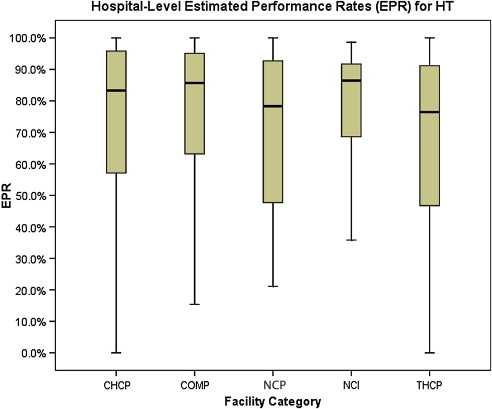

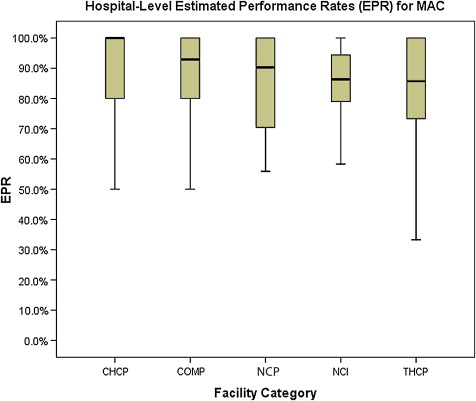

Two of the CoC’s quality of breast care measures assess the appropriate use of systemic therapies. Performance on these indicators ( Figs. 4 and 5 ) is equal across the 5 categories of CoC-accredited programs; no significant differences are noted. Adjuvant hormonal therapy, either tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor, is reported as being prescribed for between 66.9% and 78.6% of women younger than 70 years with estrogen receptor (ER)–positive, AJCC stage I (T1c), stage II, and stage III breast cancers. Multiagent chemotherapy is administered or recommended to between 81.4% and 86% of eligible women.

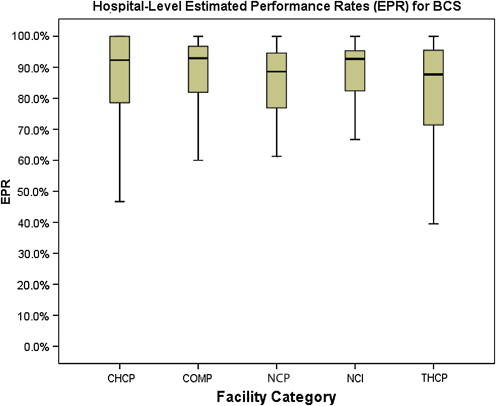

The final NQF-endorsed breast cancer measure deployed by the CoC assesses the use of adjuvant radiation therapy for women younger than 70 years who undergo breast-conserving surgery ( Fig. 6 ) and is also met without statistically significant differences across CoC categories, with performance rates ranging from 81.2% to 88.4%.

These 3 breast NQF measures are currently available to all CoC-accredited hospitals in the form of CP3R, using data that are approximately 18 months old. A new initiative of the CoC, currently being beta tested across the country at 65 facilities, is the Rapid Quality Reporting System (RQRS). This effort, which requires timely abstracting of selected data elements, provides institutions with almost real-time quality metrics on their patients with breast cancer using the same 3 NQF measures. The goal of this initiative was to enhance the ability for cancer programs to identify quality issues and rectify them in a timely fashion, preventing patients from “falling through the cracks.”

Surgical Treatment Administered

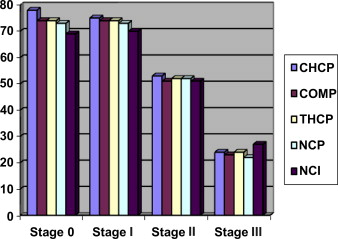

Overall rates of breast-conserving surgery were 74.3%, 73.6%, 51.5%, and 23.6% for stages 0, I, II, and III, respectively. Table 2 shows that there was some observed variation among the categories of cancer programs, with Community Hospital Cancer Programs reporting the highest breast conservation rates for stages 0, I, and II at 77.6%, 75%, and 52.6%, respectively. The NCI programs had, on average, significantly lower rates of breast-conserving surgery for stages 0 and I (69.1% and 70.3%, respectively), which might be explained by the larger proportion of younger women seen at the institutions of NCI. A program with a higher percentage of very young women would also be expected to have a higher percentage of mutation carriers, for whom bilateral total mastectomy is often the most appropriate procedure at the time of diagnosis with breast cancer. Drs Nelson and Greene address breast conservation rates in the community setting in a separate article of this issue ( Fig. 7 ).

| AJCC Stage | Surgery of the Primary Site | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast-Conserving Surgery | Mastectomy | ||

| Stage 0 | CHCP | 77.6% | 22.4% |

| COMP | 74.4% | 25.6% | |

| THCP | 74.1% | 25.9% | |

| NCP | 73.4% | 26.6% | |

| NCI | 69.1% | 30.9% | |

| Total | 74.3% | 25.7% | |

| 46,400 | 16,021 | ||

| Stage I | CHCP | 75.0% | 25.0% |

| COMP | 73.8% | 26.2% | |

| THCP | 73.6% | 26.4% | |

| NCP | 73.0% | 27.0% | |

| NCI | 70.3% | 29.7% | |

| Total | 73.6% | 26.4% | |

| 87,454 | 31,303 | ||

| Stage II (A,B) | CHCP | 52.6% | 47.4% |

| COMP | 51.1% | 48.9% | |

| THCP | 51.8% | 48.2% | |

| NCP | 51.6% | 48.4% | |

| NCI | 50.7% | 49.3% | |

| Total | 51.5% | 48.5% | |

| 42,960 | 40,471 | ||

| Stage III (A,B,C) | CHCP | 23.8% | 76.2% |

| COMP | 23.0% | 77.0% | |

| THCP | 24.2% | 75.8% | |

| NCP | 21.7% | 78.3% | |

| NCI | 27.1% | 72.9% | |

| Total | 23.6% | 76.4% | |

| 7042 | 22,801 | ||

Surgical treatment of the axilla was analyzed for stages I to III, stratified by nodal status (negative or positive) and category of the program. Patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy were excluded. The use of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLN biopsy) and/or complete axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) was similar across all facility categories. Among node positive patients, complete axillary dissection was performed more frequently in mastectomy cases versus breast-conserving cases (18% vs 14%). This did not vary across program categories. In 7.5% of N0 patients, there was no axillary node sampling documented. Of this group, 55% were 70 years or older, a group for which axillary nodal staging might reasonably be omitted in many cases. In addition, there was a higher percentage of patients with 1 or more comorbid condition (19%) in this group in comparison with the entire population (13%).

Among the node-negative patients, only 52% underwent SLN alone, ranging from 47% in community programs to 58% in NCI programs. Few N0 patients, perhaps 2%, might be predicted to have ALND because of the failure of SLN mapping, but most patients with pathologic stage N0 would be expected to have SLN alone. This finding warrants further investigation, as does the surprisingly high incidence of ALND among node negative patients.

Among the node-positive patients, complete axillary dissection with or without sentinel node biopsy was done in about 88% of patients and only a sentinel node biopsy was performed in 10% of patients. Across all facility categories, SLN biopsy alone in node positive patients was twice as likely in breast conservation surgery than with mastectomy (14% vs 7%). It is likely that many of these cases involved patients with minimal disease identified in SLNs, not detected at the initial definitive surgical procedure. The percentage of node-positive patients who did not have ALND but did have axillary-specific radiation cannot be determined from the data examined. Patients with minimal disease seen in the SLNs may also have declined a return to the operating room. In addition, some recent reports support the use of sentinel node biopsy alone for patients with positive sentinel nodes. The risk of axillary recurrence seems to be less. It might be anticipated that in subsequent years, the percentage of patients with no axillary dissection for positive sentinel nodes will increase.

Five-Year Survival Data

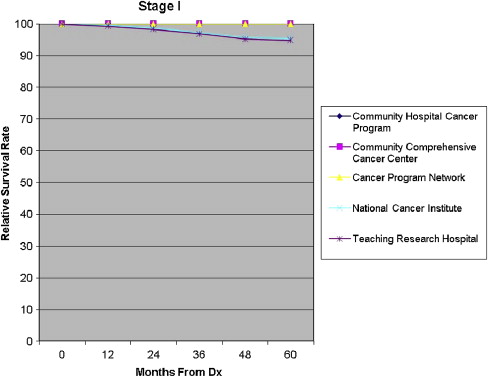

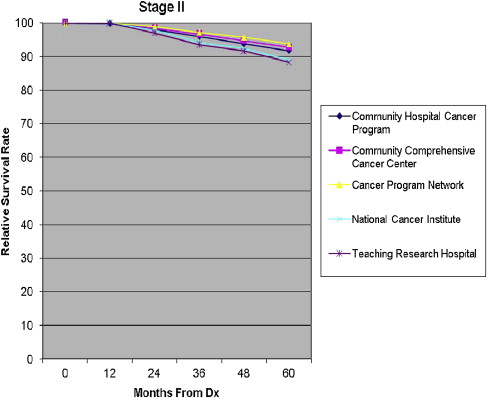

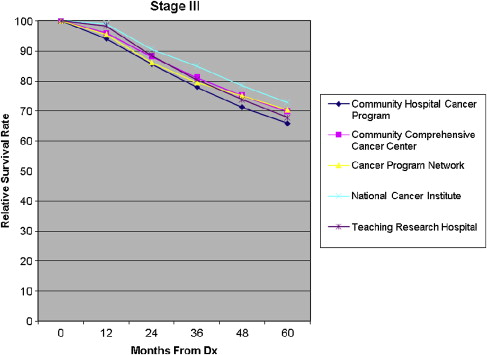

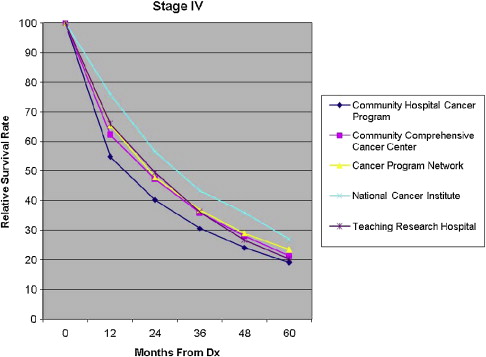

Five-year all-cause mortality was analyzed for all patients with breast cancer diagnosed in 2003. Relative survival (adjusted to the general life expectancy of the US population by age, race, and gender) and multivariate analyses (adjusted for age, insurance type, race, income, tumor grade, comorbidity, and type of treatment) were reviewed. The survival rates were compared stage by stage among the program categories ( Figs. 8–11 ).

For patients in stages I and III, the Community Hospital Cancer Programs had a statistically significantly lower likelihood of survival compared with NCI and academic programs. The interpretation of and conclusions drawn from these data should be made with caution because of the possible confounding factors. Community hospitals may be more likely to document mortality for their patients, who receive all their care locally, in typically smaller catchment areas and thus have a patient population that is comparatively more accessible for follow up. Nevertheless, some variation in survival rate is not surprising, and the observed differences are not substantial. The larger facilities have higher volumes of patients with breast cancer, provide a wider and possibly more comprehensive range of services for patients, and are more likely to have high-volume, breast-focused surgeons or surgical oncologists. The survival benefit, although not huge, could be related to the experience gained with higher volumes, use of more specialized services, and perhaps the implementation of more clinical trials. An article of this issue is devoted to a discussion of differences in outcome related to differences in hospital and physician volume.

Numerous previous reports have identified survival differences based on ethnicity, insurance type, and income level. Results shown in this article seem to be consistent with these earlier reported findings. Even among patients in stage 0, there was a statistically significant lower likelihood of survival for Medicaid patients compared with those with private insurance or managed care. Across all other stages, survival was lower for Medicaid patients and Medicare patients, relative to private insurance or managed care. African Americans fared worse than white patients across all stages except stage 0. Such differences in survival rates imply possible disparities in treatment; however, no firm conclusions about treatment disparities are evident from these data.

In summary, our review of NCDB breast cancer treatment patterns and outcomes suggests that small incremental differences in breast-conserving surgery rates, extent of axillary surgery, and all-cause mortality for stages 0 and III breast cancer exist between the lower volume community cancer programs and the higher volume NCI and Teaching Hospital Cancer Programs. These differences could be explained by other confounding factors, but the impact of high-volume versus low-volume breast surgeons on some of these results cannot be excluded. In addition, the impact (if any) of CoC accreditation on minimizing or eradicating differences in care provided cannot be determined from these data.

The Community Breast Surgeon in 2010: What Is the Job Description?

The role of the breast surgeon has evolved over the last several decades. Previously, patients presented with palpable breast masses and were treated with mastectomy if the open biopsy and frozen-section analysis diagnosed breast cancer. There was no discussion of the possible options of therapy and no opportunity to educate women about their disease. Women were often in the hospital for a week after mastectomy, and support groups were conducted in the hospital during this recovery. Wanting more involvement in their own care, women demanded that there be some discussion of options and that consideration of breast-conserving surgery be part of that discussion. Screening mammograms began to be more common, and breast cancers were diagnosed at an earlier stage, thereby allowing more women to be able to save their breasts. Newer and more effective adjuvant treatment options also became available, and the survival rate of patients with breast cancer has improved annually since the early 1990s.

With these significant changes, the role of the breast surgeon has changed. The breast surgeon is most often the first physician to discuss with the patients the details of their diagnosis and the potential options of therapy available to them based on their individual situation. Breast cancer size, grade, axillary nodal status, hormone receptors, and her-2/neu expression are available and are part of the discussion. It is recommended that most breast cancers be diagnosed through a needle biopsy, so that those discussions can take place before any surgical procedure. Patients with larger tumors can be offered neoadjuvant chemotherapy or hormonal therapy. Surgeons must also be aware of and inform the patients about the available clinical trials.

The initial breast surgical consultation now involves review of the breast imaging, review of the pathology report, discussion of the options of therapy including systemic therapy and radiation therapy options, and recommendations for any neoadjuvant treatment. Referrals for fertility consultation and plastic surgery consultation are considered. Breast surgeons must be up-to-date on all aspects of breast cancer care, not just the surgical aspects. Written material provided from various sources may enhance but not replace a thorough discussion of the patient’s case. Knowledge of national guidelines for treatment, such as National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines, is important, as is knowledge of the latest research results that can guide the most effective therapy for that patient.

The surgeon works as a team with the radiologists and pathologists as well as the medical and radiation oncologists. Attention to details in the operating room such as orientation of all breast specimens, knowledge of sentinel node biopsies, use of ultrasound in the operating room to localize lesions and reduce the rate of positive margins, oncoplastic breast surgery techniques to improve cosmesis, referral to a genetic counselor, and involvement of plastic surgeons for contralateral procedures to provide breast symmetry are all important tools a breast surgeon uses. The breast surgeon’s consultations with his or her patient can take several hours and occur for more than 1 day. Postoperatively, the breast surgeon must explain the pathology report fully and make appropriate referrals to medical and radiation oncologists. Multidisciplinary conferences are helpful to discuss imaging and histology among colleagues and to arrive at consensus regarding the appropriate next step for the patient.

Who Performs Breast Surgery in the United States?

Fifty percent of general surgeons perform a low volume of breast surgery ( Table 3 ). In a study by Porter of 519 Canadian surgeons, 42% performed less than 2 breast cancer surgeries per month and 76% of surgeons surveyed took care of patients with breast cancer less than 25% of the time. Neuner, in a study of 987 US surgeons, showed that about 50% of patients with breast cancer were cared for by doctors who performed 12 or fewer breast cancer surgeries over a 2-year period. Luther’s study found that 42% of surgeons performed less than 2 breast cancer surgeries per year. Mikeljevic, at St James Hospital in Leeds, UK, has shown in a retrospective population-based study that patients with breast cancer treated by surgeons who treated less than 10 patients per annum had a statistically significant worse survival relative to patients treated by surgeons who treated more than 50 patients per annum ( Table 4 ). The 5-year survival rate was 60% and 68%, respectively. Sentinel node biopsy success rates have been associated with a higher volume of breast cancer cases. Other studies have found no strong correlation between surgeon’s volume of cases and patient outcomes.